A Theory of Cinematic Memory and an Aesthetics of Nostalgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PACKING, UNPACKING, and REPACKING the CINEMA of GUY MADDIN George Melnyk University of Calgary

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 2011 REVIEW ESSAY: PACKING, UNPACKING, AND REPACKING THE CINEMA OF GUY MADDIN George Melnyk University of Calgary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Melnyk, George, "REVIEW ESSAY: PACKING, UNPACKING, AND REPACKING THE CINEMA OF GUY MADDIN" (2011). Great Plains Quarterly. 2683. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2683 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. REVIEW ESSAY Playing with Memories: Essays on Guy Maddin. Edited by David Church. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2009. xiii + 280 pp. Grayscale photography section, notes, filmography, bibliography, index. $29.95 paper. Into the Past: The Cinema of Guy Maddin. By William Beard. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010. xii + 471 pp. Photographs, appendix, notes, bibliography, index. $85.00 cloth, $37.95 paper. Guy Maddin's "My Winnipeg." By Darren Wershler. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010. 145 pp. Photographs, production credits, notes, bibliography. $45.00 cloth, $17.95 paper. My WinniPeg. By Guy Maddin. Toronto: Coach House Press, 2009. 191 pp. Photographs, film script, essays, interview, filmography, miscellanea. $27.95 paper. PACKING, UNPACKING, AND REPACKING THE CINEMA OF GUY MADDIN Guy Maddin is Canada's most unusual film director, allowed him to create a genuinely maker. -

Guy Maddin Y El Fin Del Cine: Donde Habitan Los Monstruos Raúl Hernández Garrido [email protected]

fre Guy Maddin y el fin del cine: donde habitan los monstruos RAúl HeRnández GARRido [email protected] Guy Maddin and the end of cinema: where the monsters dwell Abstract From 1985 Guy Maddin has created an exemplary filmography composed of thirteen films and almost forty shortfilms. By crisscrossing particular techniques of the silent cinema and primitive cinematographies with a very personal theme, he has disrupted the modes of narration and representation, as well as proposing a singular rewriting of the history of cinema. Key words : Silent cinema. Postclassical cinema. Avant-garde. Deconstruction. Simulacrum. Incest Resumen Desde 1985 Guy Maddin ha creado, a través de trece largometrajes y casi cuarenta cortometrajes, una filmogra - fía ejemplar en la que, cruzando técnicas propias de los filmes silentes y de cinematografías primitivas con una temática muy personal, convulsiona los modos de la narración y representación y propone una singular reescri - tura de la historia del cine. Palabras clave: Cine silente. Cine postclásico. Vanguardia. Deconstrucción. Simulacro. Incesto. ISSN. 1137-4802. pp. 107-121 Anclándose en un ya moribundo siglo XX, es en 1985 cuando la muy par - ticular filmografía del canadiense Guy Maddin, tan desigual como fascinan - te, arranca. Para comprender mejor su obra deberíamos volver la mirada a algunos años antes, cuando Maddin, a través de las series documentales de Kevin Brownlow ( Hollywood, 1980 ) descubre y empieza a ver películas silen - tes y a sentirse fascinado por su variedad de formas de expresión. Su primera película, de forma ejemplar, se llama The Dead Father , el padre muerto. The Dead Father (Guy Maddin, 1985) Raúl Hernández Garrido t& 10f8 Junto a la figura del Padre, muerto y sin embargo presente, molesto y penoso, autoritario pero no sujeto a una ley, muchas veces competidor o estúpido adversario del protagonista, otras convertido en un zombi sin voluntad, la personalidad fuerte de la Madre dominará su filmografía. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

2011 Fargo Film Festival Program

1 AROUND THE WORLD IN 11 YEARS... COMING FULL CIRCLE... Dear Fargo Film Festival Audiences, On March 1, 2001 an intrepid band of film lovers held our collective breaths as we waited for the press to show up for the opening press conference of our very first Fargo Film Festival. The press arrived as did award winning filmmakers Rob Nilson and John Hanson to celebrate the screening of their North Dakota-produced and Cannes Film Festival award winner, Northern Lights. On opening night, March 1, 2011, the Fargo Film Festival again celebrates North Dakota culture, history, and film making with The Lutefisk Wars and Roll Out, Cowboy. Over the years, our festival journey has circled the globe from Fargo to Leningradsky to Rwanda to Antarctica, all without leaving the cushy seats of our very own hometown Fargo Theatre. Some of you have been my traveling companions from the very Margie Bailly Emily Beck FARGO THEATRE FARGO THEATRE beginning of this 11 year cinematic tour. Including Fargo Film Festival 2011 Volunteer Spirit Award Winner, Marty Jonason. Executive Director Film Programmer My heartfelt thanks! Whether you are a long-time film traveler or just beginning your festival journey, “welcome aboard”. In 2012, Fargo Theatre Film Programmer Emily Beck will take over as your festival tour guide. You will be in very good hands. You’ll find me in the front row of the balcony “tripping out” on massive amounts of popcorn and movies, movies, movies. Margie Bailly EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR • HISTORIC FARGO THEATRE DAN FRANCIS PHOTOGRAPHY FARGO THEATRE STAFF: -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

From Weimar to Winnipeg: German Expressionism and Guy Maddin Andrew Burke University of Winnipeg (Canada) E-Mail: [email protected]

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 16 (2019) 59–79 DOI: 10.2478/ausfm-2019-0004 From Weimar to Winnipeg: German Expressionism and Guy Maddin Andrew Burke University of Winnipeg (Canada) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The films of Guy Maddin, from his debut feature Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988) to his most recent one, The Forbidden Room (2015), draw extensively on the visual vocabulary and narrative conventions of 1920s and 1930s German cinema. These cinematic revisitations, however, are no mere exercise in sentimental cinephilia or empty pastiche. What distinguishes Maddin’s compulsive returns to the era of German Expressionism is the desire to both archive and awaken the past. Careful (1992), Maddin’s mountain film, reanimates an anachronistic genre in order to craft an elegant allegory about the apprehensions and anxieties of everyday social and political life. My Winnipeg (2006) rescores the city symphony to reveal how personal history and cultural memory combine to structure the experience of the modern metropolis, whether it is Weimar Berlin or wintry Winnipeg. In this paper, I explore the influence of German Expressionism on Maddin’s work as well as argue that Maddin’s films preserve and perpetuate the energies and idiosyncrasies of Weimar cinema. Keywords: Guy Maddin, Canadian film, German Expressionism, Weimar cinema, cinephilia. Any effort to catalogue completely the references to, and reanimations of, German Expressionist cinema in the films of Guy Maddin would be a difficult, if not impossible, task. From his earliest work to his most recent, Maddin’s films are suffused with images and iconography drawn from the German films of the 1920s. -

The Forbidden Room

© Galen Johnson The Forbidden Room Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson Producer David Christensen, Phoebe Greenberg, Penny Mancuso, A submarine in distress, a lumberjack who mysteriously appears to the Phyllis Laing. Production companies Phi Films (Montreal, crew – wasn’t he just in the dark forests of Holstein-Schleswig rescuing Canada); Buffalo Gal Pictures (Winnipeg, Canada); National the beautiful Margot from the claws of the Red Wolves? A neurosurgeon Film Board of Canada (Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Director who digs deeply into the brain of a manic patient; a murderer who pretends Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson. Screenplay Guy Maddin, Evan to be the victim of his own killings; a traumatised young woman „on the Johnson, Robert Kotyk. Director of photography Stephanie Deutsch-Kolumbianisch Express somewhere between Berlin and Bogota“; Weber-Biron, Ben Kasulke. Production design Galen Johnson. seductive skeletons, zeppelins colliding, and a hot bath that seems to have Set design Brigitte Henry, Chris Lavis, Maciek Szczerbowski. triggered the whole thing. Guy Maddin’s rampant, anarchic film, co-directed Costume Elodie Mard, Yso South, Julie Charland. Sound Simon by Evan Johnson, resembles an apparently chaotic, yet always significant Plouffe, David Rose, John Gurdebeke, Vincent Riendeau, Gavin eroto-claustrophobic nightmare that never seems to want to end, in which Fernandes. Editor John Gurdebeke. the plot, characters and locations constantly flow into one another in truly With Roy Dupuis, Clara Furey, Louis Negin, Céline Bonnier, enigmatic style. The countless fantastic plotlines are structured like the Karine Vanasse, Caroline Dhavernas, Paul Ahmarani, Mathieu intertwined arms of a spiral nebula – all of them inspired by real, imagi- Amalric, Udo Kier, Maria de Medeiros, Charlotte Rampling, nary and photographic memories of films from the silent era now lost, to Geraldine Chaplin. -

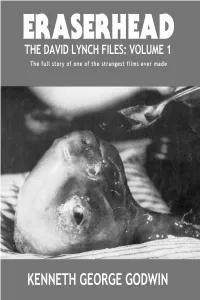

ERASERHEAD the David Lynch Files: Volume 1

ERASERHEAD The David Lynch Files: Volume 1 Kenneth George Godwin This book is for sale at http://leanpub.com/lynch This version was published on 2016-02-12 This is a Leanpub book. Leanpub empowers authors and publishers with the Lean Publishing process. Lean Publishing is the act of publishing an in-progress ebook using lightweight tools and many iterations to get reader feedback, pivot until you have the right book and build traction once you do. © 1981, 1982 and 2015 Kenneth George Godwin To David Lynch, whose first feature changed the course of my life. Contents Introduction .......................... 1 Eraserhead: An Appreciation ................ 5 Introduction Spike In the summer of 1980, David Lynch’s first feature, Eraserhead, showed up at what was at the time Winnipeg’s main repertory cinema, The Festival on Sargent Avenue. The theatre was run by Greg Klimkiw (later Guy Maddin’s original producer) whom I knew from our in-print rivalry as film reviewers for the two University student newspapers – Greg for the University of Manitoba’s Man- itoban, and me for the University of Winnipeg’s Uniter. Although we had occasionally tossed barbs at each other, there was no actual animosity and when Greg took over the Festival, he handed me a “free lifetime pass”. The initial booking for Eraserhead was just for a weekend. Having read something about it in the previous year or two, I was eager to see it and went with a friend to the first showing. I was hooked from the opening image, found myself sucked into a remarkably dense, sustained imaginary world every detail of which fascinated me. -

A Film by Guy Maddin

ARCHANGEL a film by guy maddin A WEIRD AND WILD MELODRAMA OF OBSESSIVE LOVE archangel is set in the northernmost tip of old imperial russia in the winter of 1919. the great war has been over for three months, but no one has remembered to tell those who remain in the town of archangel. maddin’s stunning black and white cinema tography and memorably stylized set design make this a film quite unlike any other. 1990 | 83 MINUTES | B & W presented by the winnipeg film group “This is a great occasion for me, the fresh reprinting of a movie I enjoyed making more than any other before or since, and which has lain dormant for so long! This movie hearkens back to the days of my In the spring of 2008 most primordial filmic obsessions and even I will be puzzled to figure out exactly who I was when the Winnipeg Film Group completed the striking of four new 35mm film I attempted to mount this thing. I would like to thank Monica Lowe of the wfg, the AV Trust and prints of Guy Maddin’s classic 1990 as always, Dave Barber, for the happy resurrection and screening of this, for me, most precious filmArchangel . Filmed in Winnipeg, and personal oddity.” Manitoba in the summer of 1989, – Guy Maddin Archangel is a stunning and surreal- istic tragedy of the Great War and it’s release brought Maddin the U.S. Na- “You haven’t seen a truly foreign film until you’ve seen a Guy Maddin film.” tional Society of Film Critics’ prize –David Cronenberg for Best Experimental Film of the Year in 1991. -

A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases

A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases PRACTICE RESEARCH MAX TOHLINE ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Max Tohline The genealogies of the supercut, which extend well past YouTube compilations, back Independent scholar, US to the 1920s and beyond, reveal it not as an aesthetic that trickled from avant-garde [email protected] experimentation into mass entertainment, but rather the material expression of a newly-ascendant mode of knowledge and power: the database episteme. KEYWORDS: editing; supercut; compilation; montage; archive; database TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Tohline, M. 2021. A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases. Open Screens, 4(1): 8, pp. 1–16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/os.45 Tohline Open Screens DOI: 10.16995/os.45 2 Full Transcript: https://www.academia.edu/45172369/Tohline_A_Supercut_of_Supercuts_full_transcript. Tohline Open Screens DOI: 10.16995/os.45 3 RESEARCH STATEMENT strong patterning in supercuts focuses viewer attention toward that which repeats, stoking uncritical desire for This first inklings of this video essay came in the form that repetition, regardless of the content of the images. of a one-off blog post I wrote seven years ago (Tohline While critical analysis is certainly possible within the 2013) in response to Miklos Kiss’s work on the “narrative” form, the supercut, broadly speaking, naturally gravitates supercut (Kiss 2013). My thoughts then comprised little toward desire instead of analysis. more than a list; an attempt to add a few works to Armed with this conclusion, part two sets out to the prehistory of the supercut that I felt Kiss and other discover the various roots of the supercut with this supercut researchers or popularizers, like Tom McCormack desire-centered-ness, and other pragmatics, as a guide. -

BIEFF 2018 Edition Catalogue

2017 THEME PROGRAMS Special Acknowledgments to all the filmmakers, producers and distributors whose films are screened in BIEFF 2018 and to the following persons and institutions: 4 Concept 64 BERLINALE SPOTLIGHT: Alessandro Raja – Festival Scope Corina Burlacu – Eastwards Joost Daamen – IDFA International Documentary Mirsad Purivatra – Sarajevo Film Festival 6 Festival Board FORUM EXPANDED Alexander Nanau – Film Monitor Association Cornelia Popa – Cinelab Romania Film Festival Amsterdam Monica Anita – TNT Alexandru Berceanu – CINETic Cristian Ignat – Canopy Juan José Felix – Embassy of the Republic of Natalia Andronachi – Austrian Cultural Forum 8 Festival Team 76 IDENTITY AND BELONGING: Adina-Ioana Șuteu – French Institute Bucharest Cristiana Tăutu – British Council Romania Argentina Natalia Trebik – Le Fresnoy Studio National des Alina Raicu – Embassy of Canada in Romania Cristina Niculae – Peggy Production Juhani Alanen – Tampere International Short Film Arts Contemporains SARAJEVO THEME PROGRAM Ana Agopian – CINEPUB Cristina Nițu – Fala Português Festival Nicolae Mandea – UNATC National University of 9 UNATC / UNARTE Presentation Ana Androne – Embassy of the Kingdom of the Cristina Petrea – Manekino Film Jukka-Pekka Laakso – Tampere International Theatre and Film Bucharest 84 A DUTCH PERSPECTIVE: Netherlands Dana Berghes – National Museum of Short Film Festival Paolo Moretti – Festival of Documentary Film 10 Partner Festivals ROTTERDAM THEME PROGRAM Ana Mișu – TH Hotels Contemporary Art MNAC Bucharest Kevin Hamilton - Embassy of Canada -

Festival Catalogue 2015

Jio MAMI 17th MUMBAI FILM FESTIVAL with 29 OCTOBER–5 NOVEMBER 2015 1 2 3 4 5 12 October 2015 MESSAGE I am pleased to know that the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival is being organised by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) in Mumbai from 29th October to 5th November 2015. Mumbai is the undisputed capital of Indian cinema. This festival celebrates Mumbai’s long and fruitful relationship with cinema. For the past sixteen years, the festival has continued promoting cultural and MRXIPPIGXYEP I\GLERKI FIX[IIR ½PQ MRHYWXV]QIHME TVSJIWWMSREPW ERH GMRIQE IRXLYWMEWXW%W E QYGL awaited annual culktural event, this festival directs international focus to Mumbai and its continued success highlights the prominence of the city as a global cultural capital. I am also happy to note that the 5th Mumbai Film Mart will also be held as part of the 17th Mumbai Film Festival, ensuring wider distribution for our cinema. I congratulate the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image for its continued good work and renewed vision and wish the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and Mumbai Film Mart grand success. (CH Vidyasagar Rao) 6 MESSAGE Mumbai, with its legacy, vibrancy and cultural milieu, is globally recognised as a Financial, Commercial and Cultural hub. Driven by spirited Mumbaikars with an indomitable spirit and great affection for the city, it has always promoted inclusion and progress whilst maintaining its social fabric. ,SQIXSXLI,MRHMERH1EVEXLM½PQMRHYWXV]1YQFEMMWXLIYRHMWTYXIH*MPQ'ETMXEPSJXLIGSYRXV] +MZIRXLEX&SPP][SSHMWXLIQSWXTVSPM½GMRHYWXV]MRXLI[SVPHMXMWSRP]FI½XXMRKXLEXE*MPQ*IWXMZEP that celebrates world cinema in its various genres is hosted in Mumbai.