“Make a Home Run for Suffrage”: Promoting Women's Emancipation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY a Long March for Suffrage

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Margaret Fuller was born in Cambridge in1810. By her late teens, she was considered a prodigy and equal or superior in intelligence to her male friends. As an adult she hosted “Conversations” for men and women on topics that ranged from women’s rights to philosophy. She joined Ralph Waldo Emerson in editing and writing for the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial from 1840-1842. It was in this publication that she wrote an article about women’s rights titled, “The Great Lawsuit,” which she would go on to expand into a book a few years later. In 1844, she moved to NYC to write for the New York Tribune. Her book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in1845. She traveled to Europe as the Tribune’s foreign correspondent, the first woman to hold such a role. She died in a shipwreck off the coast of NY in July 1850 just as she was returning to life in the U.S. Her husband and infant also perished. It was hoped that she would be a leader in the equal rights and suffrage movements but her life was tragically cut short. 02 SARAH BURKS, CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL COMMISSION December 2019 CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Harriet A. Jacobs (1813-1897) was born into slavery in Edenton, NC. She escaped her sexually abusive owner in 1835 and lived in hiding for seven years. In 1842 she escaped to the north. She eventually was able to secure freedom for her children and herself. -

The National Pastime and History: Baseball And

' • • • •• • , I ' • • • • " o • .. , I O • \ •, • • ,' • ' • • • I • ' I • • THE NATIONAL PASTIME AND HISTORY: BASEBALL AND AMERICAN SOCIETY'S CONNECTION DURINGTHE INTERWAR YEARS A THESIS SUBMITTED INPARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY KRISTINA BIRCH, B.A. DENTON, TEXAS MAY2007 TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY DENTON, TEXAS April 5, 2007 To the Dean of the Graduate School: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by KristinaBirch entitled "The National Pastime and History: Baseball and American Society's Connection During the Interwar Years." I have examined this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the degree of Master of Artswith a major in History. , h.D., Major Professor e read this thesis an its acceptance: epartment Chair Accepted: )j� DeanJE=F� of the Graduate School ABSTRACT KRISTINA BIRCH THE NATIONAL PASTIME AND HISTORY: BASEBALL AND AMERICAN SOCIETY'S CONNECTIONDURING THE INTERWARYEARS MAY2007 "The National Pastime and History: Baseball and American Society's Connection During the Interwar Years" examines specificconnections between Major League Baseball and society during the 1920s and 1930s. The economics of Baseball and America, the role of entertainment, and the segregation practiced by both are discussed in detail to demonstrate how Major League Baseball and society influencedea ch other. There is a brief look at both America and Baseball prior to and during World War I to provide an understanding of America and Major League Baseball at the dawn of the 1920s. -

A Historical Examination of the Institutional Exclusion of Women from Baseball Rebecca A

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 No Girls in the Clubhouse: A Historical Examination of the Institutional Exclusion of Women From Baseball Rebecca A. Gularte Scripps College Recommended Citation Gularte, Rebecca A., "No Girls in the Clubhouse: A Historical Examination of the Institutional Exclusion of Women From Baseball" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 86. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/86 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NO GIRLS IN THE CLUBHOUSE: A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF THE INSTITUTIONAL EXCLUSION OF WOMEN FROM BASEBALL By REBECCA A. GULARTE SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR BENSONSMITH PROFESSOR KIM APRIL 20, 2012 1 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my reader, Professor Bensonsmith. She helped me come up with a topic that was truly my own, and guided me through every step of the way. She once told me “during thesis, everybody cries”, and when it was my turn, she sat with me and reassured me that I would in fact be able to do it. I would also like to thank my family, who were always there to encourage me, and give me an extra push whenever I needed it. Finally, I would like to thank my friends, for being my library buddies and suffering along with me in the trenches these past months. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner

2 / AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES JOURNAL Volume 28, Spring/Summer 2021 AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES JOURNAL Volume 28, Spring/Summer / 3 Enjoy your next road trip to one of our 500+ client cities. Let this be your guide for AboutAbout thethe CoCovverer shopping, dining, lodging, recreation, entertainment & historic points of interest for the AMERICAN HERITAGE TOURIST www.AmericanAntiquities.com The history of sports in sport and protection, and it America shows that Ameri- was believed that knocking can football, indoor American down these kegels, or pins, football, baseball, softball, with a rock would pardon and indoor soccer evolved out their sins. of older British (Rugby foot- Golf’s history in the U.S. ball, British baseball, Round- dates to at least 1657, when ers, and association football) two drunk men were arrested sports. American football and for breaking windows by baseball differed greatly from hitting balls with their clubs the European sports from in Albany, New York. which they arose. Baseball However, no real traction was has achieved international gained until the early 19th popularity, particularly in century. In 1894 the United East Asia and Latin America, States Golf Association was while American football is formed to become exactly that, American Football. ambassadors for the game in Lacrosse and surfing arose the states, which by 1910 was from Native American and host to 267 golf clubs. Native Hawaiian activities Fishing is an important part that predate Western contact. of American history. It helped Horse racing remained the people survive long before the leading sport in the 1780-1860 United States was ever formed. era, especially in the South. -

![ABSTRACT Title of Document: [Re]Integrating the Stadium](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5615/abstract-title-of-document-re-integrating-the-stadium-475615.webp)

ABSTRACT Title of Document: [Re]Integrating the Stadium

ABSTRACT Title of Document: [Re]integrating the Stadium Within the City: A Ballpark for Downtown Tampa Justin Allen Cullen Master of Architecture, 2012 Directed By: Professor Garth C. Rockcastle, FAIA Architecture With little exception, Major League Baseball stadiums across the country deprive their cities of valuable space when not in use. These stadiums are especially wasteful if their resource demands are measured against their utilization. Baseball stadiums are currently utilized for only 13% of the total hours of each month during a regular season. Even though these stadiums provide additional uses for their audiences (meeting spaces, weddings, birthdays, etc.) rarely do these events aid the facility’s overall usage during a year. This thesis explores and redevelops the stadium’s interstitial zone between the street and the field. The primary objective is to redefine this zone as a space that functions for both a ballpark and as part of the urban fabric throughout the year. [RE]INTEGRATING THE STADIUM WITHIN THE CITY: A BALLPARK FOR DOWNTOWN TAMPA By Justin Allen Cullen Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture 2012 Advisory Committee: Professor Garth C. Rockcastle, Chair Assistant Professor Powell Draper Professor Emeritus Ralph D. Bennett Glenn R. MacCullough, AIA © Copyright by Justin Allen Cullen 2012 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my family and friends who share my undying interest in our nation’s favorite pastime. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents and my fiancé, Kiley Wilfong, for their love and support during this six-and-a-half year journey. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Usa Intercollegiate Fb (Gridiron)Independent Clubs 1882/83-1886/87 1882/83 Seasonal Data 1883/84 Seasonal Data 1884/85 Seaso

USA INTERCOLLEGIATE FB NEW YORK AC(NYC) ( - - ) (GRIDIRON)INDEPENDENT CLUBS No records 1882/83-1886/87 PATERSON TOWN TEAM(NJ) (0-1-0) H 11/29 New York City(NYU)Univ 2-4 1882/83 SEASONAL DATA UPLAND AA(PA) ( - - ) USA INTERCOLLEGIATE FOOTBALL H 12/07 Chester Cricket FBC(no score) INDEPENDENT CLUBS DIVISION I BERGEN PT. AC(NJ) ( - - ) USA INTERCOLLEGIATE FOOTBALL INDEPENDENT N 11/30 Bergen Pt. Canvassbacks(no score) CLUBS DIVISION II 1883/84 BERGEN PT.CANVASSBACKS(NJ) ( - - ) EAST HARTFORD CLUB(CT) (1-1-0) N 11/30 Bergen Pt. AC(no score) Hannum’s Business Coll L-W N 12/01 Hannum’s Business Coll 8-6 BERGEN PT. MYSTICS(NJ) ( - - ) @ Ward Park, Hartford,CT; 10 East Hartford Men to 11 N Elizabeth City AC(no score) College Men N 11/30 Elizabeth City AC(no score) @ New York Gun Club Grounds,NYC HARLEM VOLUNTEERS(NYC) (0-2-0) St Johns(Fordham)Coll Div II 6-15 EAST NEW YORK AC(NY) (2-0-0) St Johns(Fordham)Coll Div II 6-20 N 11/18 Brooklyn Poly Inst (f) 1-0 H 11/30 Golden Anchor FBC(NYC) W-L HARTFORD CITY GUARD(CT) ( - - ) N 11/29 Hartford Company K(no score) ELIZABETH CITY AC(NJ) ( - - ) @ Ward Street Grounds,Hartford,CT N Bergen Pt. Mystics(no score) N 11/30 Bergen Pt. Mystics(no score) HARTFORD COMPANY K(CT) ( - - ) @ New York Gun Club Grounds,NYC N 11/29 Hartford City Guard(no score) @ Ward Street Grounds,Hartford,CT GOLDEN ANCHOR FBC(NYC) (0-1-0) A 11/30 East New York AC(NY) L-W JAMAICA PLAIN TOWN TEAM(MA) (0-1-0) H 11/09 Roxbury Latin Sch 0-16 NEW YORK AMERICAN AA(NYC) (0-2-0) Att. -

1944 All-American Girls Baseball League

HISTORY MAKER BASEBALL 1944 All-American Girls Professional Baseball League One of the top movies of 1992 was the film “A League of Their Own,” starring Tom Hanks, Geena Davis, Rosie O’Donnell and Madonna, a story about a women’s professional baseball league formed during World War II. The movie was a critical and commercial success, earning glowing reviews, topping the box office by its second week of release, and earning over $150 million in ticket sales. The catch phrase, “There’s no crying in baseball!”—uttered by Rockford Peaches manager Jimmy Dugan (played by Hanks) made the American Film Instutute’s list of Greatest Movie Lines of All-Time, and the film itself was selected by the Library of Congress in 2012 for preservation in the National Film Registry, as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.” Interestingly, when the film opened in ’92, relatively few of the people who saw it knew that it was based on an actual, real-life league—many thought it was complete fiction. But the fictionalized account portrayed in the movie was, in fact, based on a very real story. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League was formed in 1943 out of concern that with so many players serving in World War II, big league baseball might be forced to suspend operations. The idea was that perhaps women could keep the game active and on the minds of baseball fans until the men could return from the war. The new league was bankrolled by big league owners, conducted nation-wide tryouts to stock its four inaugural teams with talented women players, and began competitive play in the spring of ’43—just as the movie’s screenplay detailed. -

Landis, Cobb, and the Baseball Hero Ethos, 1917 – 1947

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 Lindsay John Bell Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bell, Lindsay John, "Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18066. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18066 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconstructing baseball’s image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 by Lindsay John Bell A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural Agricultural Technology and Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Lawrence T. McDonnell, Major Professor James T. Andrews Bonar Hernández Kathleen Hilliard Amy Rutenberg The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Lindsay John Bell, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

Base Ball. Trap Shooting and General Sports

, _..:.^, Jr_.,.. ^ - DEYOTBD TO BASE BALL. TRAP SHOOTING AND GENERAL SPORTS Volume 39, No. 10. Philadelphia, May 24, 1902. Price, Five Cents. PLAYERS JPUNISHED THE STATESHOOT. FOR NOT DOING THE "ALPHONSE- | HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL MEETING HELD GASTON" ACT ON THE FIELD. AT OIL CITY. The National League Executive Cora- Large Attendance of Shooters Atkin- mittee Indefinitely Suspends the Two son Led in State Events Crosby Freds, Clarke and Tenney, For the High in Open Brey Won Target Fisticuffs on the Pittsburg Diamond. Championship Bollmaa Live Bird. Chicago, May 16. -Manager Fred Clarke, When the Oil City Gun Club signified a of Pittslmi©g, and First Baseman Tenney, desire to hold the 1902 tournament of the of Boston, have bees indefinitely suspended Pennsylvania State Sportsmen©s Associa by tne Board of Control of tion there was no opposi the National .League for en tion, as pleasant memories gaging in a fist tight on the "f the 1897 meet were still Pitt.sburg grounds during fresh in the minds of those Hie game yesterday. The who went to Oil City that announcement of the sus year. So it came about pension was made to-day that the Oil City Gun Club liy President James A. was given the 1902 meet liart, who is a member of at the convention held last the Board, and it, marks a year in Allentown. From new era in the history of the first the Oil City men the National League, as it worked for the success of has been, a long time since the twelfth annual tourna summary measures have ment of the P. -

Suffrage Organizations Chart.Indd

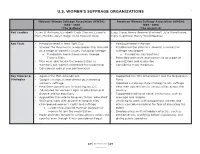

U.S. WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE ORGANIZATIONS 1 National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), 1869 - 1890 1869 - 1890 “The National” “The American” Key Leaders Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Lucy Stone, Henry Browne Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, Mott, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Anna Howard Shaw Mary Livermore, Henry Ward Beecher Key Facts • Headquartered in New York City • Headquartered in Boston • Started The Revolution, a newspaper that focused • Established the Woman’s Journal, a successful on a range of women’s issues, including suffrage suffrage newspaper o Funded by a pro-slavery man, George o Funded by subscriptions Francis Train • Permitted both men and women to be a part of • Men were able to join the organization as organization and leadership members but women controlled the leadership • Considered more moderate • Considered radical and controversial Key Stances & • Against the 15th Amendment • Supported the 15th Amendment and the Republican Strategies • Sought a national amendment guaranteeing Party women’s suffrage • Adopted a state-by-state strategy to win suffrage • Held their conventions in Washington, D.C • Held their conventions in various cities across the • Advocated for women’s right to education and country divorce and for equal pay • Supported traditional social institutions, such as • Argued for the vote to be given to the “educated” marriage and religion • Willing to work with anyone as long as they • Unwilling to work with polygamous women and championed women’s rights and suffrage others considered radical, for fear of alienating the o Leadership allowed Mormon polygamist public women to join the organization • Employed less militant lobbying tactics, such as • Made attempts to vote in various places across the petition drives, testifying before legislatures, and country even though it was considered illegal giving public speeches © Better Days 2020 U.S.