To His Coy Mistress’.” Marvell Studies 6(1): 2, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FANTASY NEWS TEN CENTS the Science Fiction Weekly Newspaper Volume 4, Number 21 Sunday, May 12

NEWS PRICE: WHILE THREE IT’S ISSUES HOT! FANTASY NEWS TEN CENTS the science fiction weekly newspaper Volume 4, Number 21 Sunday, May 12. 1940 Whole Number 99 FAMOUS FANTASTIC FACTS SOCIAL TO BE GIVEN BY QUEENS SFL THE TIME STREAM The next-to-last QSFL meeting which provided that the QSFL in Fantastic Novels, long awaited The Writer’s Yearbook for 1940 of the 39-40 season saw an attend vestigate the possibilities of such an companion magazine to Famous contains several items of consider ance of close to thirty authors and idea. The motion was passed by a Fantastic Mysteries, arrived on the able interest to the science fiction fans. Among those present were majority with Oshinsky. Hoguet. newsstands early this week. This fan. There is a good size picture of Malcolm Jameson, well know stf- and Unger on investigating com new magazine presents the answer Fred Pohl, editor of Super Science author; Julius Schwartz and Sam mittee. It was pointed out that if to hundreds of stfans who wanted and Astonishing, included in a long Moskowitz, literary agents special twenty fans could be induced to pay to read the famous classics of yester pictorial review of all Popular Pub izing in science fiction; James V. ten dollars apiece it would provide year and who did not like to wait lications; there is also, the informa Taurasi. William S. Sykora. Mario two hundred dollars which might months for them to appear in serial tion that Harl Vincent has had ma Racic, Jr., Robert G. Thompson, be adequate to rent a “science fiction terial in Detective Fiction Weekly form. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

X-Men Legacy: 5 Miles South of the Universe Pdf, Epub, Ebook

X-MEN LEGACY: 5 MILES SOUTH OF THE UNIVERSE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Carey,Steve Kurth | 152 pages | 14 Mar 2012 | Marvel Comics | 9780785160670 | English | New York, United States X-Men Legacy: 5 Miles South of the Universe PDF Book A weak 5 out of I really do. Yeah, it's just the faces that get so skewed by Kurth - like they all have weird tumours. Edgar Tadeo Inker ,. This is also the final issue of X-Men: Legacy. While she does find Marvel Girl and make friends with a crew of pirates, the other half of her crew are battling a horde of insectoid ali Mike Carey has been tasked with the impossible - bringing back Havok, Polaris, and Marvel Girl from the depths of comic lore in time for the X-Men Schism event. I am hoping that "the Days of Future Past" movie is followed up by a cosmic X-men film. Rogue is forced to confront some space pirates that constantly threaten her life. Find out here! In his role as mentor he has typically been present in the book, but he has notable absences, including issues 59—71 in government custody after the Onslaught crisis and 99— educating Cadre K in space. Rogue, Magneto, and Gambit are major characters. Community Reviews. Kate Miller rated it really liked it Jun 02, From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Comic Book Resources. X-Men Legacy Collected Editions 1 - 10 of 11 books. Welcome back. Since the introduction of X- Men , the plotlines of this series and other X-Books have been interwoven to varying degrees. -

On Ways of Studying Tolkien: Notes Toward a Better (Epic) Fantasy Criticism

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 2020 On Ways of Studying Tolkien: Notes Toward a Better (Epic) Fantasy Criticism Dennis Wilson Wise University of Arizona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Wise, Dennis Wilson (2020) "On Ways of Studying Tolkien: Notes Toward a Better (Epic) Fantasy Criticism," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol9/iss1/2 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Wise: On Ways of Studying Tolkien INTRODUCTION We are currently living a golden age for Tolkien Studies. The field is booming: two peer-reviewed journals dedicated to J.R.R. Tolkien alone, at least four journals dedicated to the Inklings more generally, innumerable society newsletters and bulletins, and new books and edited collections every year. And this only encompasses the Tolkien work in English. In the last two decades, specifically since 2000, the search term “Tolkien” pulls up nearly 1,200 hits on the MLA International Bibliography. For comparison, C. S. Lewis places a distant second at fewer than 900 hits, but even this number outranks the combined hits on Ursula K. -

Readercon 14

readercon 14 program guide The conference on imaginative literature, fourteenth edition readercon 14 The Boston Marriott Burlington Burlington, Massachusetts 12th-14th July 2002 Guests of Honor: Octavia E. Butler Gwyneth Jones Memorial GoH: John Brunner program guide Practical Information......................................................................................... 1 Readercon 14 Committee................................................................................... 2 Hotel Map.......................................................................................................... 4 Bookshop Dealers...............................................................................................5 Readercon 14 Guests..........................................................................................6 Readercon 14: The Program.............................................................................. 7 Friday..................................................................................................... 8 Saturday................................................................................................14 Sunday................................................................................................. 21 Readercon 15 Advertisement.......................................................................... 26 About the Program Participants......................................................................27 Program Grids...........................................Back Cover and Inside Back Cover Cover -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

One Story, One Reader and Two Decades of Ongoing Appeal

Narrative Attraction: One Story, One Reader and Two Decades of Ongoing Appeal Warren Maynes and Margaret Mackey University of Alberta His wellbeing appears to need spectral entities to oppose it, figures of his own invention whom he can defeat. McEwan, Saturday, 2005, 78 Margaret: Imaginative commitment is an active energizer of our mental economy, but our understanding of how that process works is amorphous and cloudy. What is it that “captures” one person’s imagination while leaving another cold? What matrix of memories, desires, terrors and needs finds expression in a particular story or even in a particular turning point of a story, so that this story plays a significant role in the shaping of someone’s ways of responding to the world? Language and Literacy 1 Volume 8 Number 2 2007 Language and Literacy This article will explore the ramifications of these questions through the lens of one young man’s ongoing response to a single story, told through multiplying media. The story is Highlander, which first appeared as a movie in 1986 and has been retold and expanded through a variety of vehicles: novelizations, sequel movies, a lengthy television series, a card game, and so forth. The fan is Warren Maynes, a recent graduate of the School of Library and Information Studies at the University of Alberta, who made a class presentation on the subject of Highlander and its ongoing hold on his own imagination for nearly twenty years. I was the instructor of that class and I was intrigued at his insider perspective on questions of narrative fascination and connection that are often completely opaque to outsiders. -

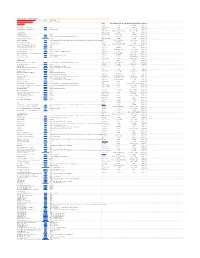

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

Ansible® 405 April 2021 from David Langford , 94 London Road, Reading, Berks, RG1 5AU, UK

Ansible® 405 April 2021 From David Langford , 94 London Road, Reading, Berks, RG1 5AU, UK. Website news.ansible.uk. ISSN 0265-9816 (print); 1740- 942X (e). Logo: Dan Steffan . Cartoon (‘Dragon’s Eye’): Ulrika O’Brien . Available for SAE, ticholama, hesso-penthol or resilian. MOVING ON. October 2021 will see the tenth anniversary of the online £50 reg; under-17s £12; under-13s free. See novacon.org.uk. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction , hosted by Orion and linked to the SOLD OUT . 21-24 Apr 2022 ! Camp SFW, Vauxhall Holiday Park, Gollancz SF Gateway ebook operation. Orion/Gollancz have now decided Great Yarmouth. See www.scifiweekender.com. All places presumably not to renew the contract on 1 October. The principal Encyclopedia taken by membership transfers from the cancelled March 2021 event. editors John Clute and David Langford plan to move sf-encyclopedia.com POSTPONED AGAIN . 27-29 May 2022 ! Satellite 7, Crowne Plaza, to their own web server and continue as seamlessly as possible with Glasgow. £70 reg (£80 at the door); under-25s £60; under-18s £20; much the same ‘look and feel’, perhaps with a new sponsor and certainly under-12s £5; under-5s £2. See seven.satellitex.org.uk. Former dates 21- with a few improvements that the current platform doesn’t allow. 23 May 2021. All existing memberships transferred to 2022; no refunds. Rumblings. DisCon III (Worldcon 2021, Washington DC), with one The Army of Unalterable Law of its two hotels not only closed but filing for bankruptcy, is unable to tell Peter S. Beagle and his current business partners regained rights ‘to members whether it will be a physical as well as a virtual convention. -

13.09.2018 Orcid # 0000-0002-3893-543X

JAST, 2018; 49: 59-76 Submitted: 11.07.2018 Accepted: 13.09.2018 ORCID # 0000-0002-3893-543X Dystopian Misogyny: Returning to 1970s Feminist Theory through Kelly Sue DeConnick’s Bitch Planet Kaan Gazne Abstract Although the Civil Rights Movement led the way for African American equality during the 1960s, activist women struggled to find a permanent place in the movement since key leaders, such as Stokely Carmichael, were openly discriminating against them and marginalizing their concerns. Women of color, radical women, working class women, and lesbians were ignored, and looked to “women’s liberation,” a branch of feminism which focused on consciousness- raising and social action, for answers. Women’s liberationists were also committed to theory making, and expressed their radical social and political ideas through countless essays and manifestos, such as Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto (1967), Jo Freeman’s BITCH Manifesto (1968), the Redstockings Manifesto (1969), and the Radicalesbians’ The Woman-Identified Woman (1970). Kelly Sue DeConnick’s American comic book series Bitch Planet (2014–present) is a modern adaptation of the issues expressed in these radical second wave feminist manifestos. Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future ruled by men where disobedient women—those who refuse to conform to traditional female gender roles, such as being subordinate, attractive (thin), and obedient “housewives”—are exiled to a different planet, Bitch Planet, as punishment. Although Bitch Planet takes place in a dystopian future, as this article will argue, it uses the theoretical framework of radical second wave feminists to explore the problems of contemporary American women. 59 Kaan Gazne Keywords Comic books, Misogyny, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Dystopia Distopik Cinsiyetçilik: Kelly Sue DeConnick’in Bitch Planet Eseri ile 1970’lerin Feminist Kuramına Geri Dönüş Öz Sivil Haklar Hareketi Afrikalı Amerikalıların eşitliği yolunda önemli bir rol üstlenmesine rağmen, birçok aktivist kadın kendilerine bu hareketin içinde bir yer edinmekte zorlandılar.