Hong Kong National Security Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media Francis L. F. Lee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.8009 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 9-18 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Francis L. F. Lee, “Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media”, China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2018, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 8009 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. -

HRWF Human Rights in the World Newsletter Bulgaria Table Of

Table of Contents • EU votes for diplomats to boycott China Winter Olympics over rights abuses • CCP: 100th Anniversary of the party who killed 50 million • The CCP at 100: What next for human rights in EU-China relations? • Missing Tibetan monk was sentenced, sent to prison, family says • China occupies sacred land in Bhutan, threatens India • 900,000 Uyghur children: the saddest victims of genocide • EU suspends efforts to ratify controversial investment deal with China • Sanctions expose EU-China split • Recalling 10 March 1959 and origins of the CCP colonization in Tibet • Tibet: Repression increases before Tibetan Uprising Day • Uyghur Group Defends Detainee Database After Xinjiang Officials Allege ‘Fake Archive’ • Will the EU-China investment agreement survive Parliament’s scrutiny? • Experts demand suspension of EU-China Investment Deal • Sweden is about to deport activist to China—Torture and prison be damned • EU-CHINA: Advocacy for the Uyghur issue • Who are the Uyghurs? Canadian scholars give profound insights • Huawei enables China’s grave human rights violations • It's 'Captive Nations Week' — here's why we should care • EU-China relations under the German presidency: is this “Europe’s moment”? • If EU wants rule of law in China, it must help 'dissident' lawyers • Happening in Europe, too • U.N. experts call call for decisive measures to protect fundamental freedoms in China • EU-China Summit: Europe can, and should hold China to account • China is the world’s greatest threat to religious freedom and other basic human rights -

2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement

! ! ! ! ! 2014-2015 Report on Police Violence in the Umbrella Movement A report of the State Violence Database Project in Hong Kong Compiled by The Professional Commons and Hong Kong In-Media ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! About!us! ! About!the!research! ! Maps!/!Glossary! ! Executive!Summary! ! 1.! Report!on!physical!injury!and!mental!trauma!...........................................................................................!13! 1.1! Physical!injury!....................................................................................................................................!13! 1.1.1! Injury!caused!by!police’s!direct!smacking,!beating!and!disperse!actions!..................................!14! 1.1.2! Excessive!use!of!force!during!the!arrest!process!.......................................................................!24! 1.1.3! Connivance!at!violence,!causing!injury!to!many!.......................................................................!28! 1.1.4! Delay!of!rescue!and!assault!on!medical!volunteers!..................................................................!33! 1.1.5! Police’s!use!of!violence!or!connivance!at!violence!against!journalists!......................................!35! 1.2! Psychological!trauma!.........................................................................................................................!39! 1.2.1! Psychological!trauma!caused!by!use!of!tear!gas!by!the!police!..................................................!39! 1.2.2! Psychological!trauma!resulting!from!violence!...........................................................................!41! -

Official Record of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 1117 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 30 November 1994 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, C.B.E., LL.D., Q.C., J.P. THE CHIEF SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL LEUNG MAN-KIN, C.B.E., J.P. THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY THE HONOURABLE SIR NATHANIEL WILLIAM HAMISH MACLEOD, K.B.E., J.P. THE ATTORNEY GENERAL THE HONOURABLE JEREMY FELL MATHEWS, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, Q.C., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, O.B.E., LL.D., J.P. THE HONOURABLE NGAI SHIU-KIT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PANG CHUN-HOI, M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE SZETO WAH THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EDWARD HO SING-TIN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FONALD JOSEPH ARCULLI, O.B.E., J.P. 1118 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 30 November 1994 THE HONOURABLE MRS PEGGY LAM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WAH-SUM, O.B.E., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEONG CHE-HUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES DAVID McGREGOR, O.B.E., I.S.O., J.P. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

Bay to Bay: China's Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US And

June 2021 Bay to Bay China’s Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US and San Francisco Bay Area Business Acknowledgments Contents This report was prepared by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute for the Hong Kong Trade Executive Summary ...................................................1 Development Council (HKTDC). Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Institute, led the analysis with support from Overview ...................................................................5 Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute who co-authored Historic Significance ................................................... 6 the paper. The Economic Institute is grateful for the valuable information and insights provided by a number Cooperative Goals ..................................................... 7 of subject matter experts who shared their views: Louis CHAPTER 1 Chan (Assistant Principal Economist, Global Research, China’s Trade Portal and Laboratory for Innovation ...9 Hong Kong Trade Development Council); Gary Reischel GBA Core Cities ....................................................... 10 (Founding Managing Partner, Qiming Venture Partners); Peter Fuhrman (CEO, China First Capital); Robbie Tian GBA Key Node Cities............................................... 12 (Director, International Cooperation Group, Shanghai Regional Development Strategy .............................. 13 Institute of Science and Technology Policy); Peijun Duan (Visiting Scholar, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Connecting the Dots .............................................. -

The Portrayal of Female Officials in Hong Kong Newspapers

Constructing perfect women: the portrayal of female officials in Hong Kong newspapers Francis L.F. Lee CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG, HONG KONG On 28 February 2000, the Hong Kong government announced its newest round of reshuffling and promotion of top-level officials. The next day, Apple Daily, one of the most popular Chinese newspapers in Hong Kong, headlined their full front-page coverage: ‘Eight Beauties Obtain Power in Newest Top Official Reshuffling: One-third Females in Leadership, Rarely Seen Internationally’.1 On 17 April, the Daily cited a report by regional magazine Asiaweek which claimed that ‘Hong Kong’s number of female top officials [is the] highest in the world’. The article states that: ‘Though Hong Kong does not have policies privileging women, opportunities for women are not worse than those for men.’ Using the prominence of female officials as evidence for gender equality is common in public discourse in Hong Kong. To give another instance, Sophie Leung, Chair of the government’s Commission for Women’s Affairs, said in an interview that women in Hong Kong have space for development, and she was quoted: ‘You see, Hong Kong female officials are so powerful!’ (Ming Pao, 5 February 2001). This article attempts to examine news discourses about female officials in Hong Kong. Undoubtedly, the discourses are complicated and not completely coherent. Just from the examples mentioned, one could see that the media embrace the relatively high ratio of female officials as a sign of social progress. But one may also question the validity of treating the ratio of female officials as representative of the situation of gender (in)equality in the society. -

Minutes of the 27Th Meeting Held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 Pm on Friday, 25 June 2021

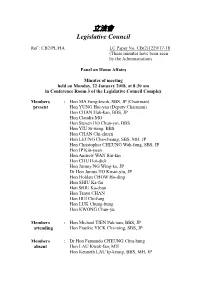

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1238/20-21 Ref : CB2/H/5/20 House Committee of the Legislative Council Minutes of the 27th meeting held in Conference Room 1 of the Legislative Council Complex at 2:30 pm on Friday, 25 June 2021 Members present : Hon Starry LEE Wai-king, SBS, JP (Chairman) Hon MA Fung-kwok, GBS, JP (Deputy Chairman) Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, GBS, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, GBS, JP Hon WONG Ting-kwong, GBS, JP Hon CHAN Hak-kan, BBS, JP Hon CHAN Kin-por, GBS, JP Hon WONG Kwok-kin, SBS, JP Hon Mrs Regina IP LAU Suk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Paul TSE Wai-chun, JP Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP Hon Steven HO Chun-yin, BBS Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming, SBS, JP Hon YIU Si-wing, BBS Hon CHAN Han-pan, BBS, JP Hon LEUNG Che-cheung, SBS, MH, JP Hon Alice MAK Mei-kuen, BBS, JP Hon KWOK Wai-keung, JP Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, SBS, JP Hon Elizabeth QUAT, BBS, JP Hon Martin LIAO Cheung-kong, GBS, JP Hon POON Siu-ping, BBS, MH Dr Hon CHIANG Lai-wan, SBS, JP Ir Dr Hon LO Wai-kwok, SBS, MH, JP Hon CHUNG Kwok-pan Hon Jimmy NG Wing-ka, BBS, JP Dr Hon Junius HO Kwan-yiu, JP Hon Holden CHOW Ho-ding Hon SHIU Ka-fai, JP Hon Wilson OR Chong-shing, MH Hon YUNG Hoi-yan, JP -2 - Dr Hon Pierre CHAN Hon CHAN Chun-ying, JP Hon CHEUNG Kwok-kwan, JP Hon LUK Chung-hung, JP Hon LAU Kwok-fan, MH Hon Kenneth LAU Ip-keung, BBS, MH, JP Dr Hon CHENG Chung-tai Hon Vincent CHENG Wing-shun, MH, JP Hon Tony TSE Wai-chuen, BBS, JP Members absent : Hon Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Dr Hon Priscilla LEUNG Mei-fun, SBS, JP Clerk in attendance : Miss Flora TAI -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

En En Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2019-2024 Plenary sitting B9-0013/2019 16.7.2019 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION with request for inclusion in the agenda for a debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law pursuant to Rule 144 of the Rules of Procedure on the situation in Hong Kong (2019/2732(RSP)) Reinhard Bütikofer, Heidi Hautala, Alyn Smith, Henrike Hahn, Hannah Neumann, Alexandra Louise Rosenfield Phillips, Gina Dowding, Saskia Bricmont, Ernest Urtasun, Viola Von Cramon-Taubadel, Pierrette Herzberger-Fofana on behalf of the Verts/ALE Group RE\P9_B(2019)0013_EN.docx PE637.779v01-00 EN United in diversityEN B9-0013/2019 European Parliament resolution on the situation in Hong Kong (2019/2732(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the Basic Law of the Special Administrative Region (SAR) of Hong Kong adopted on 4 April 1990, which entered into force on 1 July 1997, – having regard to the Joint Declaration of the Government of the United Kingdom and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Question of Hong Kong of 19 December 1984, also known as the Sino-British Joint Declaration, – having regard to the joint reports of the Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of 8 May 2019 JOIN(2019) 8 final, of 26 April 2017 (JOIN(2017)0016), of 25 April 2016 on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region – Annual Report, – having regard to the Joint Communication from the Commission and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council Ref : CB2/PL/HA LC Paper No. CB(2)1229/17-18 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Panel on Home Affairs Minutes of meeting held on Monday, 22 January 2018, at 8:30 am in Conference Room 3 of the Legislative Council Complex Members : Hon MA Fung-kwok, SBS, JP (Chairman) present Hon YUNG Hoi-yan (Deputy Chairman) Hon CHAN Hak-kan, BBS, JP Hon Claudia MO Hon Steven HO Chun-yin, BBS Hon YIU Si-wing, BBS Hon CHAN Chi-chuen Hon LEUNG Che-cheung, SBS, MH, JP Hon Christopher CHEUNG Wah-fung, SBS, JP Hon IP Kin-yuen Hon Andrew WAN Siu-kin Hon CHU Hoi-dick Hon Jimmy NG Wing-ka, JP Dr Hon Junius HO Kwan-yiu, JP Hon Holden CHOW Ho-ding Hon SHIU Ka-fai Hon SHIU Ka-chun Hon Tanya CHAN Hon HUI Chi-fung Hon LUK Chung-hung Hon KWONG Chun-yu Members : Hon Michael TIEN Puk-sun, BBS, JP attending Hon Frankie YICK Chi-ming, SBS, JP Members : Dr Hon Fernando CHEUNG Chiu-hung absent Hon LAU Kwok-fan, MH Hon Kenneth LAU Ip-keung, BBS, MH, JP - 2 - Public Officers : Item III attending Dr LAW Chi-kwong, GBS, JP Chairperson of the Community Care Fund Task Force under the Commission on Poverty Secretary for Labour and Welfare Mr Patrick LI, JP Deputy Secretary for Home Affairs (1) Mr Nick AU YEUNG Principal Assistant Secretary for Home Affairs (Community Care Fund) Ms May CHAN, JP Deputy Secretary for Education (6) Mr FUNG Man-chung Assistant Director (Family and Child Welfare) Social Welfare Department Ms Ivis CHUNG Chief Manager (Allied Health) Hospital Authority Item IV Mr LAU Kong-wah, JP Secretary for Home Affairs Mr -

Association for Asian Studies, Inc., Committee on East Asian Libraries

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 1979 Number 58 Article 12 2-1-1979 No. 058 Bulletin - Association for Asian Studies, Inc., Committee on East Asian Libraries Committee on East Asian Libraries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Libraries, Committee on East Asian (1979) "No. 058 Bulletin - Association for Asian Studies, Inc., Committee on East Asian Libraries," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 1979 : No. 58 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol1979/iss58/12 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TKCH5 ..A.3SOOI-A.TI03Sr FOR A.S1JU^ STUDIES ISSTC. COMMITTEE ON EAST ASIAN LIBRARIES BULLETIN Eugene "W. Wu Onairperson Number 58 February, 1979 Editorial Note i An Announcement, iii Committee Activities 1 Meetings and Conferences , 8 Organizations and Institutions 12 Librarians 18 Articles 21 What1s New in Technical Processing , 38 Special Reports 43 Publications 52 o/o :HarvardL«"5reno:hing Literary, Harvard University a Divinity Avenue, Oarataridge, Mass. OS13B EDITORIAL NOTE With the 1979 Annual Meeting ray term as Chairperson of CEAL expires. I take leave of office with much appreciation for the opportunity of service for the past three years, and with an even greater sense of gratitude for the way you have all responded to CEAL's call for help and support. Building on CEAL's past accomplishments, we have been able to move steadily forward in search of practical and realistic solutions to the outstanding problems confronting all East Asian libraries.