The Newgate Calendar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theological Socialism of the Labour Church

‘SO PECULIARLY ITS OWN’ THE THEOLOGICAL SOCIALISM OF THE LABOUR CHURCH by NEIL WHARRIER JOHNSON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis argues that the most distinctive feature of the Labour Church was Theological Socialism. For its founder, John Trevor, Theological Socialism was the literal Religion of Socialism, a post-Christian prophecy announcing the dawn of a new utopian era explained in terms of the Kingdom of God on earth; for members of the Labour Church, who are referred to throughout the thesis as Theological Socialists, Theological Socialism was an inclusive message about God working through the Labour movement. By focussing on Theological Socialism the thesis challenges the historiography and reappraises the significance of the Labour -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 15 February 2018

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 15 February 2018 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the South team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Approve - Conditions 8 2017/10544/PA 12 Westlands Road Moseley Birmingham B13 9RH Erection of two storey side and rear and single storey forward and rear extensions Approve - Conditions 9 2017/10199/PA Kings Norton Boys School Northfield Road Kings Norton Birmingham B30 1DY Demolition of existing gymnasium sports hall and erection of replacement sports hall together with changing rooms and storage Page 1 of 1 Corporate Director, Economy Committee Date: 15/02/2018 Application Number: 2017/10544/PA Accepted: 12/12/2017 Application Type: Householder Target Date: 06/02/2018 Ward: Moseley and Kings Heath 12 Westlands Road, Moseley, Birmingham, B13 9RH Erection of two storey side and rear and single storey forward and rear extensions Applicant: Mra Nasim Jan 12 Westlands Road, Moseley, Birmingham, B13 9RH Agent: Mr Hanif Ghumra 733 Walsall Road, Great Barr, Birmingham, B42 1EN Recommendation Approve Subject To Conditions 1. Proposal 1.1. Planning consent is sought for the proposed erection of a two storey side and rear extension and single storey forward and rear extensions. 1.2. The proposed development would provide an extended living room, kitchen/dining room and hallway at ground floor level. The existing garage would be converted to a study with a small extension to this room. At first floor level two new bedrooms and a bathroom would be provided. The existing bathroom would be incorporated into the landing area and the existing third bedroom would become a second bathroom. -

Birmingham's Evangelical Free Churches and The

BIRMINGHAM’S EVANGELICAL FREE CHURCHES AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR by ANDY VAIL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY School of History & Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis demonstrates that the First World War did not have a major long-term impact on the evangelical free churches of Birmingham. Whilst many members were killed in the conflict, and local church auxiliaries were disrupted, once the participants – civil and military – returned, the work and mission of the churches mostly continued as they had before the conflict, the exception being the Adult School movement, which had been in decline prior to the conflict. It reveals impacts on local church life, including new opportunities for women amongst the Baptist and Congregational churches where they began to serve as deacons. The advent of conscription forced church members to personally face the issue as to whether as Christians they could in conscience bear arms. The conflict also speeded ecumenical co-operation nationally, in areas such as recognition of chaplains, and locally, in organising local prayer meetings and commemorations. -

IN DARKEST ENGLAND and the WAY out by GENERAL WILLIAM BOOTH

IN DARKEST ENGLAND and THE WAY OUT by GENERAL WILLIAM BOOTH (this text comes from the 1890 1st ed. pub. The Salvation Army) 2001 armybarmy.com To the memory of the companion, counsellor, and comrade of nearly 40 years. The sharer of my every ambition for the welfare of mankind, my loving, faithful, and devoted wife this book is dedicated. This e-book was optically scanned. Some minor updates have been made to correct some spelling errors in the original book and layout in-compatibilities 2001 armybarmy.com PREFACE The progress of The Salvation Army in its work amongst the poor and lost of many lands has compelled me to face the problems which an more or less hopefully considered in the following pages. The grim necessities of a huge Campaign carried on for many years against the evils which lie at the root of all the miseries of modern life, attacked in a thousand and one forms by a thousand and one lieutenants, have led me step by step to contemplate as a possible solution of at least some of those problems the Scheme of social Selection and Salvation which I have here set forth. When but a mere child the degradation and helpless misery of the poor Stockingers of my native town, wandering gaunt and hunger-stricken through the streets droning out their melancholy ditties, crowding the Union or toiling like galley slaves on relief works for a bare subsistence kindled in my heart yearnings to help the poor which have continued to this day and which have had a powerful influence on my whole life. -

CONTEXTS of the CADAVER TOMB IN. FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND a Volumes (T) Volume Ltext

CONTEXTS OF THE CADAVER TOMB IN. FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLAND a Volumes (T) Volume LText. PAMELA MARGARET KING D. Phil. UNIVERSITY OF YORK CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES October, 1987. TABLE QE CONTENTS Volume I Abstract 1 List of Abbreviations 2 Introduction 3 I The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: The Problem Stated. 7 II The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: The Surviving Evidence. 57 III The Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth Century England: Theological and Literary Background. 152 IV The Cadaver Tomb in England to 1460: The Clergy and the Laity. 198 V The Cadaver Tomb in England 1460-1480: The Clergy and the Laity. 301 VI The Cadaver Tomb in England 1480-1500: The Clergy and the Laity. 372 VII The Cadaver Tomb in Late Medieval England: Problems of Interpretation. 427 Conclusion 484 Appendix 1: Cadaver Tombs Elsewhere in the British Isles. 488 Appendix 2: The Identity of the Cadaver Tomb in York Minster. 494 Bibliography: i. Primary Sources: Unpublished 499 ii. Primary Sources: Published 501 iii. Secondary Sources. 506 Volume II Illustrations. TABU QE ILLUSTRATIONS Plates 2, 3, 6 and 23d are the reproduced by permission of the National Monuments Record; Plates 28a and b and Plate 50, by permission of the British Library; Plates 51, 52, 53, a and b, by permission of Trinity College, Cambridge. Plate 54 is taken from a copy of an engraving in the possession of the office of the Clerk of Works at Salisbury Cathedral. I am grateful to Kate Harris for Plates 19 and 45, to Peter Fairweather for Plate 36a, to Judith Prendergast for Plate 46, to David O'Connor for Plate 49, and to the late John Denmead for Plate 37b. -

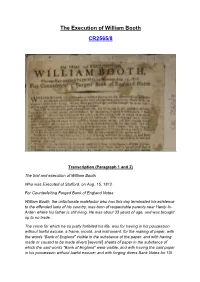

The Execution of William Booth CR2565/8

The Execution of William Booth CR2565/8 Transcription (Paragraph 1 and 2) The trial and execution of William Booth Who was Executed at Stafford, on Aug. 15, 1812. For Counterfeiting Forged Bank of England Notes William Booth, the unfortunate malefactor who has this day terminated his existence to the offended laws of his country, was born of respectable parents near Henly-In- Arden where his father is still living. He was about 33 years of age, and was brought up to no trade. The crime for which he so justly forfeited his life, was for having in his possession without lawful excuse, a frame, mould, and instrument, for the making of paper, with the words “Bank of England” visible in the substance of the paper, and with having made or caused to be made divers [several] sheets of paper in the substance of which the said words “Bank of England” were visible, and with having the said paper in his possession without lawful excuse; and with forging divers Bank Notes for 10l. 5l. and 1l. each and divers blank bank notes, for the like sums, and also for coming divers pieces of coin resembling silver Dollars and Banks Tokens; and for forging the Hemp Or die to denote the duty of four pence; and also for forging divers promissory notes of Messrs. Raikes and Co. East Riding Bank, Hull, for the payment of one guinea each. William Booth William Booth was born on Hall End Farm near Beaudesert, Warwickshire in 1776. Son of a church warden and farmer, he was one of eight children. -

Trinity Times July Edition

TRINITY TIMES JULY EDITION Trinity Times JULY 2015 60p The Magazine For The Parish of Stratford-upon-Avon Rachel Writes Page 4 Cricket Heaven Page 25 Photo: Harry Lomax Friends of Shakespeare’s Church Launch £150,000 Appeal Christianity at Work Read Ronnie Mulryne’s Feature Pages 44 & 45 Page 11 Holy Trinity Church Stratford-upon-Avon St Helen’s Church, Clifford Chambers All Saints’ Church, Luddington Address AddressLine 2 Addresine 3 Address ine 4 2 The Holy Trinity Team This Issue... In our second and packed issue check out Rachel’s vision article, on page 4, about those people who think big, but perhaps more importantly act big. The second in our series, Christianity at Work, is an important feature, written by David Ellis, about ‘The Revd Patrick Taylor Suffering Church’. It’s on page 11. Vicar And if bats and runs are your thing Pat Pilton takes us to cricketing heaven on pages 25 and 26. If a good quiz interests you, and you’re wondering about the £150,000 appeal on our cover read Ronnie Mulryne’s feature on page 44 and 45. Then check out Jonathan Drake’s News Item on page 24. Meet our new Parish Manager, Linda MacDermott, on page 15. Revd Dr Steve Bate Worship listings are on pages 6 and 7. Associate Vicar Read Val Milburn’s lovely article about The Jesus People on pages 29 and 30. St Helen’s Clifford Chambers, and All Saints’ Luddington, now have dedicated pages. In this issue go to pages 31 and 42. Geoffrey and Doreen Lees continue their history of this magazine on pages 32 and 33. -

(1952, Pp. 99-105) and Dr. Paul Balog (1955, Pp

Miscellanea 423 colleagues furnished dies for traders' tokens, or private substitutes for copper coin. He was regretfully discharged under Treasury pressure and the charges against his customers, the counterfeiters, were quietly dropped. Recent papers in the Numismatic Chronicle by Mr. Philip Grierson (1952, pp. 99-105) and Dr. Paul Balog (1955, pp. 199-201) have discussed the employment of pegged dies, and the new example cited here must considerably strengthen the presumption that the tech- nique is one peculiarly associated with forgery. Dr. Balog, too, has argued that the technique was evolved in the eighteenth century, and some support for this comes from the completely different technique of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century English forgers as exem- plified by false dies in the British Museum and Royal Mint collections (R. H. M. Dolley, B.N.J. 1953, pp. 170-1) and by the forger's dies for the joannes of 1722 preserved in the Bankfield Museum, Halifax (H. Ling Roth, The Yorkshire Coiners, p. 6). These dies are all of "box" type, the square reverse die fitting into a square collar attached to the obverse die—a technique apparently known to the Anglo- Saxons but not employed officially after c. 1130. A similar type of die appears, however, to have been used in a local mint at Shanghai as late as 1857 (H. F. Bowker, The Numismatist, Sept. 1956, pp. 993-4). One of the nineteenth-century square-headed dies from China is in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It is illustrated in the Numismatist, Oct. 1956, p. 1138. There is also a full description, pp. -

Officership in the Salvation Army I

Thesis Officership in The Salvation Army i OFFICERSHIP IN THE SALVATION ARMY A Case Study in Clericalisation by Harold Ivor Winston Hill A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2004 Thesis Officership in The Salvation Army ii In memory of A.J. Gilliard. 1899-1973 I would love to know what he would have said about it all. Thesis Officership in The Salvation Army iii Commissioning then… Illustration deleted Thesis Officership in The Salvation Army iv Commissioning now. Illustration deleted Thesis Officership in The Salvation Army v CONTENTS ABSTRACT vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii PREFACE x 1 Introduction: Of clerics, clericalism and clericalisation 2 PART ONE: THE FIRST CENTURY 46 2 Booth Led Boldly 47 3 Clerical Roles 73 4 What Manner of Men…? 109 Entr’acte: From Era of the Booths to the 1960’s 146 PART TWO: THE SECOND CENTURY 161 5 Putney Debates 167 6 Official Words 208 PART THREE: OFFICERS WHO MAY NOT BE OFFICERS 254 7 An officer by any other name… 255 8 A Monstrous Regiment of Women 304 PART FOUR: THINGS THAT ARE SHAKEN; THINGS THAT REMAIN 354 9 The International Commission on Officership 355 10 Conclusions 371 Appendices i Bibliography xl Thesis Officership in The Salvation Army vi ABSTRACT This thesis attempts an historical review and analysis of Salvation Army ministry in terms of the tension between function and status, between the view that members of the church differ only in that they have distinct roles, and the tradition that some enjoy a particular status, some ontological character, by virtue of their ordination to one of those roles in particular. -

The Visitacion of Staffordschire

- f y* 2£isitacimi oi i^taftorlrsrfrire. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of Florida, George A. Smathers Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/visitacionofstafOOgraz Trcm a JI.S. in the CcUegre rfAr'mj _ See-p. <S4. arte Fltmliiu Erioravi:7\i.- l,nJ. v : Wtsitauon of J^taffortiscinre &ofeert 6Iober, al'S Jtomerdtt ffieratt, MARE SCHALL TO nattllfam JTlotoer, al'S Urnxog &mge of armed, ANNO D'NI 1583. EDITED BY H. SYDNEY GRAZEBROOK, Esq. LONDON MITCHELL AND HUGHES, 140 WARDOUR STREET, W. 1883. Contents;. PAGE Introduction .......... vii List of Pedigrees xix What is to be performed by the Heralds at their going in Visitation 1 Somerset's Warrant, directed to the Bailiff of the Hundred of Cudleston, to summon the Esquires and Gentlemen inhabiting within the said Hundred to appear before him in order to the enregistering of their several arms and descents 2 Nomina Nobilium de Com' Stafford', 1583 3 Warrant of Summons against such as contemptuously refuse to appear upon the former warrant, to make their further appearance before the Earl Marshal 11 The manner of the Heralds' Proclamation for the disclaiming of ignoble persons . .12 Names of those who were disclaimed 14 Lay Subsidy Roll of the 18th of Elizabeth, a.d. 1576 ... 17 Names and Arms of Staffordshire Knights, temp. Edward I. 20 Anna Nobilium de Com' Stafford' ex libro antiquo in Officio Armorum 21 Arms of Staffordshire Families as represented in the gallery at Theobald's 26 Seal of the Town of Stafford, and List of the " Companie and Brotherhood," etc., of the said town 27 Seal of Lichfield, with similar List . -

The Fearful State of England: the Amalgamation of Fin-De-Siècle Anxieties and Anarchist Outrages in the Public Deconstruction of the Liberal State, 1892-1911

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 The Fearful State Of England: The Amalgamation Of Fin-De-Siècle Anxieties And Anarchist Outrages In The Public Deconstruction Of The Liberal State, 1892-1911 David R. Speicher University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Speicher, David R., "The Fearful State Of England: The Amalgamation Of Fin-De-Siècle Anxieties And Anarchist Outrages In The Public Deconstruction Of The Liberal State, 1892-1911" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 644. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FEARFUL STATE OF ENGLAND: THE AMALGAMATION OF FIN-DE-SIÈCLE ANXIETIES AND ANARCHIST OUTRAGES IN THE PUBLIC DECONSTRUCTION OF THE LIBERAL STATE, 1892-1911 A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History The University of Mississippi By DAVID R. SPEICHER May 2013 Copyright David R. Speicher 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes a series of Anarchist crimes, occurring in England from 1892- 1911, and concentrates on the public dialogue that emerged in the popular press as a result of these crimes. British newspapers and periodicals published extensively on the crimes, and the crimes became a way for the British public to discuss wide-ranging topics, such as liberalism, labor, immigration, poverty and national degeneration. -

William Booth, Karl Marx and the London Residuum ANN M

What Price the Poor? William Booth, Karl Marx and the London Residuum ANN M. WOODALL 2005 Contents List of Tables Acknowledgements Series Editor’s Preface 1 Introduction 2 The Pawnbroker’s Apprentice Introduction Industrialisation and Urbanisation Poverty Poverty in Nottingham Attitudes to Poverty Malthus Jeremy Bentham Influential Writers about Poverty Dickens Carlyle The Chartists John Wesley Chartism and Methodism in Nottingham The Old Woman of Nottingham Conclusion 3 The Reverend William Introduction The Size of the London Residuum Public Opinion of Poverty Changes in Religious Belief Natural Science Biblical Criticism Moral Feeling Evangelicalism Development of Booth’s Theology Finney and Caughey Calvinism Women’s Ministry Holiness The East End Booth’s East End Base Booth’s Early Co-workers An Organisation of the Residuum Community of Poverty Conclusion 4 The Revolutionary Philosopher Introduction Marx’s Early Concept of Poverty Paris London Learning from London Conclusion 5 The Philosopher as a Prophet? Introduction Marx and Religion Societal Redemption and the Individual The Chronology of Redemption Conclusion 6 The Making of a General Introduction Permanent Poverty in the East End Public Knowledge of Poverty Where was Religion? Diffusive Christianity and Secularism Christian Socialists The Churches and the Working Classes The Growth of the Salvation Army Failure in the East End? The Springboard for Darkest England Work with Prostitutes At the Prison Gate The ‘Maiden Tribute’ Case The Darkest England Scheme The Theology behind