Re/Defining the Imaginary Museum of National Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 223 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) George Thomas The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 S lavistische B e it r ä g e BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER • JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 223 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 GEORGE THOMAS THE IMPACT OF THEJLLYRIAN MOVEMENT ON THE CROATIAN LEXICON VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1988 George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access ( B*y«ftecne I Staatsbibliothek l Mönchen ISBN 3-87690-392-0 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1988 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, GeorgeMünchen Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 FOR MARGARET George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access .11 ж ־ י* rs*!! № ri. ur George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 Preface My original intention was to write a book on caiques in Serbo-Croatian. -

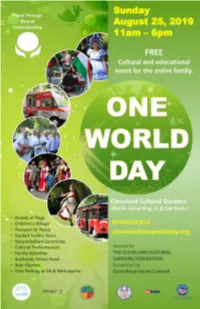

Program Booklet

The Irish Garden Club Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians Murphy Irish Arts Association Proud Sponsors of the Irish Cultural Garden Celebrate One World Day 2019 Italian Cultural Garden CUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE (TRI-C®) SALUTES CLEVELAND CULTURAL GARDENS FEDERATION’S ONE WORLD DAY 2019 PEACE THROUGH MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING THANK YOU for 74 years celebrating Cleveland’s history and ethnic diversity The Italian Cultural Garden was dedicated in 1930 “as tri-c.edu a symbol of Italian culture to American democracy.” 216-987-6000 Love of Beauty is Taste - The Creation of Beauty is Art 19-0830 216-916-7780 • 990 East Blvd. Cleveland, OH 44108 The Ukrainian Cultural Garden with the support of Cleveland Selfreliance Federal Credit Union celebrates 28 years of Ukrainian independence and One World Day 2019 CZECH CULTURAL GARDEN 880 East Blvd. - south of St. Clair The Czech Garden is now sponsored by The Garden features many statues including composers Dvorak and Smetana, bishop and Sokol Greater educator Komensky – known as the “father of Cleveland modern education”, and statue of T.G. Masaryk founder and first president of Czechoslovakia. The More information at statues were made by Frank Jirouch, a Cleveland czechculturalgarden born sculptor of Czech descent. Many thanks to the Victor Ptak family for financial support! .webs.com DANK—Cleveland & The German Garden Cultural Foundation of Cleveland Welcome all of the One World Day visitors to the German Garden of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens The German American National congress, also known as DANK (Deutsch Amerikan- ischer National Kongress), is the largest organization of Americans of Germanic descent. -

At the Margins of the Habsburg Civilizing Mission 25

i CEU Press Studies in the History of Medicine Volume XIII Series Editor:5 Marius Turda Published in the series: Svetla Baloutzova Demography and Nation Social Legislation and Population Policy in Bulgaria, 1918–1944 C Christian Promitzer · Sevasti Trubeta · Marius Turda, eds. Health, Hygiene and Eugenics in Southeastern Europe to 1945 C Francesco Cassata Building the New Man Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy C Rachel E. Boaz In Search of “Aryan Blood” Serology in Interwar and National Socialist Germany C Richard Cleminson Catholicism, Race and Empire Eugenics in Portugal, 1900–1950 C Maria Zarimis Darwin’s Footprint Cultural Perspectives on Evolution in Greece (1880–1930s) C Tudor Georgescu The Eugenic Fortress The Transylvanian Saxon Experiment in Interwar Romania C Katherina Gardikas Landscapes of Disease Malaria in Modern Greece C Heike Karge · Friederike Kind-Kovács · Sara Bernasconi From the Midwife’s Bag to the Patient’s File Public Health in Eastern Europe C Gregory Sullivan Regenerating Japan Organicism, Modernism and National Destiny in Oka Asajirō’s Evolution and Human Life C Constantin Bărbulescu Physicians, Peasants, and Modern Medicine Imagining Rurality in Romania, 1860–1910 C Vassiliki Theodorou · Despina Karakatsani Strengthening Young Bodies, Building the Nation A Social History of Child Health and Welfare in Greece (1890–1940) C Making Muslim Women European Voluntary Associations, Gender and Islam in Post-Ottoman Bosnia and Yugoslavia (1878–1941) Fabio Giomi Central European University Press Budapest—New York iii © 2021 Fabio Giomi Published in 2021 by Central European University Press Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ceupress.com An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched (KU). -

'Virginija'dimitrije Demetera

VESNA CVJETKOVIĆ-KURELEC »Virginija« Dimitrije Demetera (jezičnop ovijesni osvrt) 1 Život i rad Dimitrije Demetera (1811-1872) u hrvatskoj su književnoj i kazališnoj historiografiji višestruko istraživani. Svoju punu znanstvenu valorizaciju dobilo je sveukupno književno stvaralaštvo na hrvatskome jeziku. Pritom su utvrđeni dosadašnji stavovi o njegovu opusu, ali i revidirane ocjene o njegovim dramskim ostvarenjima. Mislimo prvenstveno na rasprave Nikole Batuši• ća, Branka Hećimovića i Darka Suvina, koje su nametnule novu interpretaciju Deme· terovih drama, pogotovu tragedije »Teuta«, pobijajući ocjene iz prošloga stoljeća i iz razdoblja modeme, QO kojima ta drama predstavlja vrhunac onovremene hrvatske dramske književnosti. 2 ))Spominjan uvijek s razlogom i pravom kao utemeljitelj suvre menog hrvatskog glumišta, on mu kao baštinu nije ostavio svoje dramsko djelo za koje su i on intimno a i mnogobrojni kritičari nakon njega smatrali da stoji u samu vrhu naše tragedije«, naglašava Nikola Batušić. 3 Osnovne primjedbe na piščevo ne· poznavanje dramaturških pravila i na neprimjerenost scenskoga jezika upućene su i na ostala dramska ostvarenja Dimitrije Demetera (dvije knjige )>Dramatičnih pokuše• nija«), dok su predlošci za opere »Porin« i ))Ljubav i zloba« uglavnom zahvaljujući glazbi uspjeli sačuvati dio svoga dramskoga naboja. Međutim, književna je historia· grafija ep »Grobnička polje« izdvojila kao ostvarenje po kojem Demeter s pravom ulazi u glavne predstavnike hrvatske književnosti devetnaestoga stoljeća. 4 Ako uz ovo djelo dodamo već istaknuto mjesto u osnivanju, razvoju i organizaciji kazališnog života u Zagrebu i ključnu ulogu koju je odigrao u pokretu ilirizma, tada je cjeloku pan udio ovoga Grka u hrvatskoj kulturi nesumnjivo velik. Zato i s pravom smatramo da svaki prilog koji može pridonijeti nešto novo u opisu njegova lika i stvaralaštva za služuje pozornost, to više ako se odnosi na gotovo neistraženu stranu Demeterova djelovanja. -

The Book Art in Croatia Exhibition Catalogue

Book Art in Croatia BOOK ART IN CROATIA National and University Library in Zagreb, Zagreb, 2018 Contents Foreword / 4 Centuries of Book Art in Croatia / 5 Catalogue / 21 Foreword The National and University Library in Croatia, with the aim to present and promote the Croatian cultural heritage has prepared the exhibition Book Art in Croatia. The exhibition gives a historical view of book preparation and design in Croatia from the Middle Ages to the present day. It includes manuscript and printed books on different topics and themes, from mediaeval evangelistaries and missals to contemporary illustrated editions, print portfolios and artists’ books. Featured are the items that represent the best samples of artistic book design in Croatia with regard to their graphic design and harmonious relationship between the visual and graphic layout and content. The author of the exhibition is art historian Milan Pelc, who selected 60 items for presentation on panels. In addition to the introductory essay, the publication contains the catalogue of items with short descriptions. 4 Milan Pelc CENTURIES OF BOOK ART IN CROATIA Introduction Book art, a constituent part of written culture and Croatian cultural heritage as a whole, is ex- ceptionally rich and diverse. This essay does not pretend to describe it in its entirety. Its goal is to shed light on some (key) moments in its complex historical development and point to its most important specificities. The essay does not pertain to entire Croatian literary heritage, but only to the part created on the historical Croatian territory and created by the Croats. Namely, with regard to its origins, the Croatian literary heritage can be divided into three big groups. -

VASE Studio Portrait of Composer Stevan Mokranjac

VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1492 Studio portrait of composer Stevan Mokranjac Object: Studio portrait of composer Stevan Mokranjac Description: Half-length frontal shot of a seated man. He is wearing a dark suit, glasses and many insignia of honor. Comment: Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac (1856, Negotin – 1914, Skopje) was a Serbian composer and music educator. His work was essential in terms of recording and organizing Valach Serbian folk poetry, which only existed in the oral tradition and can be regarded as representative of the contemporary Serbian national spirit at large. In 1899 he founded the first independent music school in Serbia with Stanislav Binički and Cvetko Manojlović: Studio portrait of composer Stevan the Serbian Music School in Belgrade. Mokranjac This photograph was the model for the © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia portrait which is printed on the current 50 Dinar banknote. Relations: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1495 Location: Belgrade Country: Serbia Type: Postcard Creator: Jovanović, Milan, (Photographer) Publisher: S.B. Cvijanović Dimensions: Artefact: 137mm x 86mm Format: Not specified Technique: Not specified Keywords: 180 Total Culture > 184 Cultural Participation 340 Structures > 344 Public Structures 450 Finance > 453 Banking 530 Arts > 533 Music 540 Commercialized Entertainment > 545 Musical Studio portrait of composer Stevan and Theatrical Productions Mokranjac 550 Individuation and Mobility > 551 Personal © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia Names 550 Individuation and Mobility > 554 Status, Role, and Prestige 560 Social Stratification https://gams.uni-graz.at/vase 1 VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1492 Copyright: Muzej Pozorišne Umetnosti Srbije Archive: Museum of Theater Art of Serbia, Inv. -

Ana Petricevic Soprano

Ana Petricevic Soprano Ana Petricevic was born in Belgrade, Serbia, where she began her musical studies at the age of 8, when she started playing the flute. She studied opera singing at the University of Music in Belgrade. Her notable achievements as a student include winning the “Biserka Cvejic” award for the most promising young soprano and the “Danica Mastilovic” award for the best student. She also won the outright 1st prize (100/100 points) at the International Competition for Chamber Music “Davorin Jenko” and 2nd Prize at the International Competition for Opera Singers “Ondina Otta” in Maribor, Slovenia. and graduated with the highest grades, interpreting the roles of Micaela (Carmen, G. Bizet) and Tatiana (Eugene Onegin, P. I. Tchaikovsky). Ms Petricevic's professional debut was a success singing the role of Georgetta (Il Tabarro, G. Puccini) at the National Theatre of Belgrade. Following that performance, she made her debut also in the role of Contessa Almaviva (Le Nozze di Figaro, W. A. Mozart). In 2012 Ms Petricevic was presented a scholarship from the fund “Raina Kabaivanska” and, shortly afterwards, moved to Modena, Italy. For the next three years she studied with the famous Bulgarian soprano at the Institute of Music Vecchi-Tonelli di Modena. In this period, he sang in numerous concerts and prestigious events, the most prominent being the beneficiary Gala concert “Raina Kabaivanska presenta i Divi d'Opera” (2014, Sofia, Bulgaria). The concert was broadcasted live on National Television. After moving to Italy, Ms Petricevic attended different masterclasses, lead by renowned artists such as soprano Mariella Devia and baritone Renato Bruson. -

VASE Studio Portrait of Composer Davorin Jenko

VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1490 Studio portrait of composer Davorin Jenko Object: Studio portrait of composer Davorin Jenko Description: Half-length shot of a man sitting next to a piano. He is wearing a dark suit adorned with insignia of honor. Comment: Davorin Jenko (1835, Dvorje – 1914, Ljubljana) was a famous Slovene composer. He is sometimes considered the father of Slovenian national Romantic music. He also composed the Serbian national anthem, 'Bože pravde' ('God of Justice') and the former Slovenian national anthem 'Naprej, zastava Slave' ('Forward, Flag of Glory!'). In 1862, he moved to the town of Pančevo in southern Vojvodina, where he worked Studio portrait of composer Davorin Jenko as the choirmaster of the local Serbian © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia Orthodox church. He later moved to Belgrade on the other side of the Austrian-Serbian border. There he worked as a composer in the Serbian National Theatre. Jenko was among the first four members of the Academy of Arts of the Royal Serbian Academy of Sciences, appointed by King Milan I of Serbia on 5 Studio portrait of composer Davorin Jenko April 1887. He lived in Serbia until 1897, © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia when he moved to Ljubljana. He was married to Vela Nigrinova, one of the first grande dames of Serbian theatre. Date: Not after 1897 Location: Belgrade Country: Serbia Type: Postcard Creator: Jovanović, Milan, (Photographer) Publisher: S.B. Cvijanović Dimensions: Artefact: 137mm x 87mm Format: Not specified -

Sanja Majer-Bobetko Hrvatska Akademija Znanosti I Umjetnosti ————

sanja majer-bobetko hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti ———— BETWEEN MUSIC AND IDEOLOGIES: CROATIAN MUSIC CRITICISM FROM THE BEGINNING TO WORLD WAR II* roatian music criticism has not yet been completely researched, and all the re- C search carried out to date has been sporadic and unsystematic. As the Croatian lands were exposed to often aggressive Austrian, Hungarian and Italian politics until World War I and in some regions even later,1 Croatian music criticism was written in Croatian, German and Italian. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Croatian was mainly the language of the lower classes. In 1843 the nobleman Ivan Kukuljević- -Sakcinski was the first to speak Croatian instead of Latin in the Croatian Parlia- ment. Yet Croatian only became the official language in 1847. To the best of our knowledge, the first ever piece of Croatian music criticism was written in 1826, in the literary and entertainment journal Luna, by an anonym- ous author writing in German.2 The musicologist Lovro Županović attributes that review to Franjo Ksaver (Serafin) Stauduar (b. 1825 or 1826; d. 1864), who was the newspaper’s publisher and editor. Stauduar wrote a report in the Wiener allgemeine Theaterzeitung on a performance of the first Croatian national opera, Ljubav i zlo- ba [Love and Malice], by Vatroslav Lisinski (1819–54), from 1846, ‘which may also mean that he was personally in charge of the theatre section in Luna’.3 The first music review concerned the five-act melodrama Viola by the German dramatist Jo- seph Auffenberg (1798–1857), with music by Georg (Juraj) Karl Wisner von Mor- * Part of this text results from research conducted within the project ‘Networking through music: Changes of paradigms in the “Long 19th Century” – from Luka Sorkočević to Franjo Ks. -

VASE Group Shot of Artists Celebrating Davorin Jenko's Birthday

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by GAMS - Asset Management System for the Humanities VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1470 Group shot of artists celebrating Davorin Jenko's birthday Object: Group shot of artists celebrating Davorin Jenko's birthday Description: Outdoor group photograph of actors and actresses in front of a building. All of them are wearing modern clothes. Some are holding glasses in their hands. The faces of a woman and a man looking out of a Group shot of artists celebrating Davorin window in the door on the right of the Jenko's birthday building can also be seen. © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia Comment: Davorin Jenko (1835, Dvorje – 1914, Ljubljana) was a famous Slovene composer. He is sometimes considered the father of Slovenian national Romantic music. He also composed the Serbian national anthem, 'Bože pravde' ('God of Justice') and the former Slovenian national anthem 'Naprej zastava Slave' ('Forward, Flag of Glory!'). In 1862, he moved to the town of Pančevo in southern Vojvodina, where he worked as the choirmaster of the local Serbian Orthodox church. He later moved to Belgrade on the other side of the Austrian-Serbian border. There he worked as a composer in the Serbian National Theatre. Jenko was among the first four Group shot of artists celebrating Davorin Jenko's birthday members of the Academy of Arts of the © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia Royal Serbian Academy of Sciences, appointed by King Milan I of Serbia on 5 April 1887. -

Searchable PDF Format

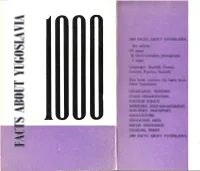

- !-l t(xt0 trA(i'l's Atr()U'I' YUGOSLAVIA (t) 4tlr eclitiorr a-\ l2tl pagcs rl -30 lrltck.unrl-wlriIc photographs - 3 rrraps - Lurrgrr:tgt's: tinglish, French, -) (icrrnitn, I\rssian, Spanish 'l'lris b<xrk c:ontuins the basic facts E- llrorrt Yrrgttslavia GT]o(;I{APIIY, I{ISTORY, r-\ w-) S ATF, OR.GANIZATION, AA IIOREIGN POLICY, WORKTJRS' SELF-MANAGEMENT, -t INDT]STRY, TRANSPORT, ACRICULTURE, a EDUCATION, ARTS, E- SOCIAL INSURANCE, (J TOURISM, SPORT IOOO FACTS ABOUT YUGOST.AVIA r= O waRszAwA .^*-h-;; c_-?6 =i PUBLISHER IZDAVACKI ZAVOD "IUGOSLAVI.I A. Beograd, Nemamjiaa 34 FACTS ABOUT YI]GOSIAYIA COUNTRY AND POPULATION GEOGRAPHIC AREA POSITION The Social srt Federral Rerpub,lic of y,urgoslavia lies, u,ith its greater part (g0 percent) in the Balkan peninsula, Southeast Europe, and, with a smaller part (20 percent) in Central Europe. Since its southwestern ,regions occupy a long length of the Adriati,c coastal be1t, it is b,oth a continental and a maritime country. The country,s extreme points extend from 40o 57' to 460 53, N. lat. and from 13" 23' to 23o 02' E. l"ong. It is consequently pole, closer to the Equator than to the North and and Italy. it has the Central European Standard time. POPULATION AND BOUNDARIES ITS NATIONAL STRUCTURE Yugoslavia is bounded by several states and the sea. On the land side, it borders on seven states: Austria and Hungary on the north, Rumania on the northeast, Bulgaria on the east, Greece on the south, Albania on the southwest and Italy on the northwest. -

CSR Projects Education

PARTNERSHIP & COMMUNITY CSR projects Education The professional association “The Ambassadors of sustainable development and environment“, a national operator of the program Young Ecoreporters, supported by the Electric Power Industry of Serbia, organizes a competition called “Energy Efficiency in view of Young Ecoreporters“ for young people 11 to 21 years old. From their own point of view, ecoreporters are to deal with is- sues related to reduction of energy consumption in their reports, which would be in a form of an essay in writing, photo or video. The young are encouraged to deal with issues on how to use energy more efficiently, how to have better quality of life, and how to pay less at the school level or in their households. The international program Young Ecoreporters is aimed at training the young how to take a stand and to report on local issues and problems in the environ- ment. The program offers to young enthusiasts a possibility for their voice to be heard because the best papers will be promoted both on local and interna- tional level. The program has been implemented for more than 20 years and YOUNG at the moment, 35 countries, where national competitions are organized, take part in it and the winner papers are sent to international competitions. The ECO- competitions are organized every year in order to encourage the young from all over the world to improve themselves, learn and investigate and to imply to environmental problems in order to motivate a local community to solve REPORTERS these. The final goal is to take initiatives for solving the global environmental problems by solving the local problems.