Choreography#7 : Performance Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Performance in Photography

PHOTOGRAPHY (A CI (A CI GENDER PERFORMANCE IN PHOTOGRAPHY (A a C/VFV4& (A a )^/VM)6e GENDER PERFORMANCE IN PHOTOGRAPHY JENNIFER BLESSING JUDITH HALBERSTAM LYLE ASHTON HARRIS NANCY SPECTOR CAROLE-ANNE TYLER SARAH WILSON GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose: front cover: Gender Performance in Photography Claude Cahun Organized by Jennifer Blessing Self- Portrait, ca. 1928 Gelatin-silver print, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 11 'X. x 9>s inches (30 x 23.8 cm) January 17—April 27, 1997 Musee des Beaux Arts de Nantes This exhibition is supported in part by back cover: the National Endowment tor the Arts Nan Goldin Jimmy Paulettc and Tabboo! in the bathroom, NYC, 1991 €)1997 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Cibachrome print, New York. All rights reserved. 30 x 40 inches (76.2 x 101.6 cm) Courtesy of the artist and ISBN 0-8109-6901-7 (hardcover) Matthew Marks Gallery, New York ISBN 0-89207-185-0 (softcover) Guggenheim Museum Publications 1071 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10128 Hardcover edition distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 100 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10011 Designed by Bethany Johns Design, New York Printed in Italy by Sfera Contents JENNIFER BLESSING xyVwMie is a c/\rose is a z/vxose Gender Performance in Photography JENNIFER BLESSING CAROLE-ANNE TYLER 134 id'emt nut files - KyMxUcuo&wuieS SARAH WILSON 156 c/erfoymuiq me c/jodt/ im me J970s NANCY SPECTOR 176 ^ne S$r/ of ~&e#idew Bathrooms, Butches, and the Aesthetics of Female Masculinity JUDITH HALBERSTAM 190 f//a« waclna LYLE ASHTON HARRIS 204 Stfrtists ' iyjtoqra/inies TRACEY BASHKOFF, SUSAN CROSS, VIVIEN GREENE, AND J. -

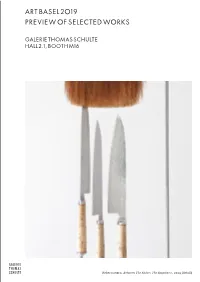

Art Basel 2019 Preview of Selected Works

ART BASEL 2019 PREVIEW OF SELECTED WORKS GALERIE THOMAS SCHULTE HALL 2.1, BOOTH M16 • Rebecca Horn, Between The Knives The Emptiness, 2014 (detail) Artists on view Also represented Contact Angela de la Cruz Dieter Appelt Galerie Thomas Schulte Hamish Fulton Alice Aycock Charlottenstraße 24 Rebecca Horn Richard Deacon 10117 Berlin Idris Khan David Hartt fon: +49 (0)30 2060 8990 Jonathan Lasker Julian Irlinger fax: +49 (0)30 2060 89910 Michael Müller Alfredo Jaar [email protected] Albrecht Schnider Paco Knöller www.galeriethomasschulte.de Pat Steir Allan McCollum Juan Uslé Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle Thomas Schulte Stephen Willats Robert Mapplethorpe PA Julia Ben Abdallah Fabian Marcaccio [email protected] Gordon Matta-Clark João Penalva Gonzalo Alarcón David Reed +49 (173) 66 46 623 Leunora Salihu [email protected] Iris Schomaker Katharina Sieverding Eike Dürrfeld Jonas Weichsel +49 (172) 30 89 074 Robert Wilson [email protected] Luigi Nerone +49 (172) 30 89 076 [email protected] Juliane Pönisch +49 (151) 22 22 02 70 [email protected] Galerie Thomas Schulte is very pleased to present at this year’s Art Basel recent works by Rebecca Horn, whose exhibition Body Fantasies will be on view at Basel’s Museum Tinguely during the time of the fair (until 22 September). Our booth will also feature works by Angela de la Cruz, Hamish Fulton, Idris Khan, Jonathan Lasker, Michael Müller, Albrecht Schnider, Pat Steir, Juan Uslé and Stephen Willats. This brochure represents a selection of the works at our booth. For further information and to learn more about works which are not shown here, please do not hesitate to contact us. -

Biographies Randy Chan Randy Chan Is an Award-Winning Architect

YEO WORKSHOP Gillman Barracks SG +65 67345168 [email protected] www.yeoworkshop.com 1 Lock Road, S (108932) Biographies Randy Chan Randy Chan is an award-winning architect and artist. Chan’s architectural and design experience crosses multiple fields and scales, all guided by the simple philosophy that architecture and aesthetics are part of the same impulse. Chan is the principal of Zarch Collaboratives - one of Singapore’s leading architectural studios established in 1999. The objective of the studio is to practice and fulfil architectural projects but also cross disciplines and approach the means of spatial design. They have worked on a series of exhibition spaces, stage set designs, art installations, world expositions and catered for private and public housing plans. Additionally, Chan is the creative director of Singapore: Inside Out, an international platform featuring a collection of multi-disciplinary experiences created by practicing artists. It is a platform with a global intention. It accommodates and presents the creative talents of Beijing, London, New York and Singapore. Artistically it combines the varying disciplines of architecture, design, fashion, film, food, music, performance and the visual arts. Hubertus von Amelunxen Professor Dr. Hubertus von Amelunxen was born in Hindelang, Germany in 1958. He lives in Berlin and Switzerland. After studies in French and German Literature and in Art History at the Philipps- Universität, Marburg and the École Normale Supérieure de Paris, he wrote his Ph.D. on Allegory and Photography: Inquiries into 19th Century French Literature. He was professor of Cultural Studies and the Founding Director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Research at the Muthesius Academy of Architecture, Design and Fine Arts in Kiel between 1995 and 2000. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Fondation Antoine De Galbert - from November 4Th 2005 to January 15Th 2006

la maison rouge - fondation antoine de galbert - from November 4th 2005 to January 15th 2006 It’s a narrow door, but for me it’s the only one. I know that history is not just dates, that it’s constantly in motion, slow and subterranean, but the fact is that I work on a property of photography, something only it has. This is its supposed lit- erality. Finally, there is the insignificance of my position. In the field, I do what I can, and that’s it. No omniscient vision, no dominant perspective… (…) Can you say something about this formalization? The words only come afterwards, after you’ve found… Being an artist is nothing, or at least, not enough; what you want is to be a poet. You are articulating sounds that are still form- less, inventing what looks like a possible route. And yet that view of the exhibition is the essence of the thing. All you’re ever doing is translat- ing an attitude and rationalizing an intuition, using first of Luc Delahaye all what is specific to photography. There is the refusal of Luc Delahaye has taken photographs for four years from places style and the refusal of style and the refusal of sentimental- newspapers report on every day: war zones, areas of conflicts ism, there is the measuring of the distance that separates me or power struggles, places where “History” is made, at the very from what I see. There is also the will to be like a servant of moment the events happen. His direct approach reminds one the image, of its rigorous demands: to take the camera where of a reporter. -

Dieter Appelt: Forth Bridge — Cinema

Centre Canadien d’Architecture 1920, rue Baile Canadian Centre for Architecture Montréal, Québec Canada H3H 2S6 t 514 939 7000 f 514 939 7020 www.cca.qc.ca communiqué /press release For immediate release Tangent | Dieter Appelt: Forth Bridge — Cinema. Metric Space the CCA presents a major new work by the renowned German artist Montréal, 24 February 2005 – From 9 March to 22 May 2005 in the Octagonal Gallery, the Canadian Centre for Architecture announces the opening of Dieter Appelt: Forth Bridge — Cinema. Metric Space, an exhibition presenting a major new work inspired by the spectacular late nineteenth-century Forth Rail Bridge near Edinburgh in Scotland. This second Tangent exhibition curated by Hubertus von Amelunxen, visiting curator of the CCA photographs collection, presents Dieter Appelt's monumental eight-part photographic tableau commissioned in 2002 by the CCA, together with conceptual drawings for the project. The exhibition also includes a provocative selection of images from the CCA’s vast archive on the Forth Bridge, most notably, photographs by Evelyn George Carey (1858–1932), a young engineer who became the official project photographer for the engineering firm of John Fowler and Benjamin Baker responsible for the design of the bridge. The CCA Tangent project was conceived to engage artists in new reflection on the relationship between photography and architecture, beginning with a corpus of photographs selected by von Amelunxen, from the CCA's vast collection—materials conceived as the beginning of a phrase to be completed by the artist. Invited to the CCA in the spring of 2002, Dieter Appelt was immediately drawn to the CCA's large archive on the Forth Bridge, which he had first seen and photographed more than 25 years earlier, and which still held great fascination for him. -

Après Eden the Walther Collection La Maison Rouge

Après Eden The Walther Collection la maison rouge Exhibition October 17, 2015 – January 17, 2016 Press Release Après Eden The Walther Collection Exhibition: October 17, 2015 – January 17, 2016 Opening preview: Friday, October 18 from 6 to 9 p.m. Press Preview from 4 to 6 p.m. Curator: Simon Njami Since its opening, each autumn la maison rouge of a four-building museum complex in has shown a major international collection. a residential area of Neu-Ulm / Berlafingen, Beginning October 17th, 2015, Artur Walther’s the town where he was born in southern Germany. exceptional collection of photography He has supported photographic programmes will be on view. Over a period of twenty years, and grants for the past twenty years. Artur Walther Artur Walther has assembled significant and began collecting in the late 1990s: first works cohesive ensembles, beginning with German by contemporary German photographers photography, then American, and later African – particularly Bernd and Hilla Becher, and and Asian photography. August Sander – before opening his collection to photography and video art from around the globe. His is now the largest collection Après Eden will present of contemporary Asian and African photography a selection of over 900 works in the world. by some fifty artists. Curator: Historical photography, Simon Njami daguerreotypes, contemporary As well as founding the Ethnicolor Festival in 1987, photography, video works, Simon Njami has curated numerous exhibitions, journals and late nineteenth- and was one of the first to show contemporary century albums have been African artists internationally. Between 2001 chosen by the curator, and 2007, he was artistic director of the African Simon Njami, to form Photography Biennial - Rencontres de Bamako. -

Copertina / Cover Story Lisa Borgiani Reportage

€ 6,20 - D.L. 353/2003 (convertito Poste in Legge 27/02/2004 Italiane n° 46) art. 1, s.p.a. comma 1 CN/AN - Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale T S TORNQUI ORRIT J 2016 @ E Y TOR S ER V O C OTHER HE T /i/ OPERTINA C TRA L L’A ** E /^/ A ! /i A ! /WR/^/ > D.L. 353/2003 (convertito in Legge 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. 1, € comma 1 CN/AN 6,20 - Poste Italiane s.p.a. - Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale A • € 12,50 | B • € 8,90 | F • € 10,90 | D • € 12,50 | UK • £ 9,20 | CH-CHF • € 11,90 | CH-TI CHF € 11,50 | P € 8,90 | P | CH-TI CHF € 11,50 • € 12,50 | B 8,90 F 10,90 D UK £ 9,20 CH-CHF 11,90 A COPERTINA / COVER STORY LISA BORGIANI REPORTAGE: BIASI IN NEW YORK E AO=! /ä/A/ä*A/^/EAA!/ä/Aä<ä A¸ ää/</i/THE OPINION BY STEFANO ZECCHI !/ /^/ä>E!/i/ ;ä*!/^/;ää/^/*/^/;;;A *AA!OY//>!>A/;EäO/ä/Aä<ä L’ALTRA COPERTINA / THE OTHER COVER STORY JORRIT TORNQUIST ää/i/@ www.fondazionegeiger.org Opening hours: daily from 4 to 8 pm - Free admission Free - pm 8 to 4 from daily hours: Opening tel. +39 0586 635011 0586 +39 tel. Aperto tutti i giorni h.16,00-20,00-Ingresso libero h.16,00-20,00-Ingresso giorni i tutti Aperto “Mash - up. Marilù Manzini” [email protected] testo di Philippe Daverio (LI) Cecina 32, Guerrazzi piazza 26|03-15|05|2016 a Dynamic Meditation March 31 - May 22 6 settembre - 18 settembre Set per intestazione su foglio verticale Set Setper perintestazione intestazione su fogliosu foglio Vernissage martedì 6 settembre h. -

Overview Exhibitions Worldwide 2021 (PDF)

1 – i f 02 a 2 T R E A D V I E W L D L I L N R G O W E X S H N I B O I I T ifa TRAVELLING EXHIBITIONS WORLDWIDE 2021 AN ATLAS OF COMMONING: PLACES OF COLLECTIVE PRODUCTIONS 4 NEW ARE YOU FOR REAL 8 ARNO FISCHER. PHOTOGRAPHY 12 BARBARA KLEMM. LIGHT AND DARK: PHOTOGRAPHS FROM GERMANY 16 THE WHOLE WORLD A BAUHAUS 20 NEW EVROVIZION. CROSSING STORIES AND SPACES 24 FABRIK. ON THE CIRCULATION OF DATA, GOODS, AND PEOPLE 28 FUTURE PERFECT: CONTEMPORARY ART FROM GERMANY 32 HELGA PARIS. PHOTOGRAPHY 36 ARTSPACE GERMANY 40 LINIE LINE LINEA: CONTEMPORARY DRAWING 44 MARCEL ODENBACH: TRANQUIL MOTIONS 48 NEW OLDS: DESIGN BETWEEN THE POLES OF TRADITION AND INNOVATION 52 OTTO DIX. “SOCIAL CRITICISM” 1920-1924; “WAR“, ETCHINGS 1924 56 PAULA MODERSOHN-BECKER AND THE WORPSWEDERS: DRAWINGS AND PRINTS 1895-1906 60 PURE GOLD – UPCYCLED! UPGRADED! 64 ROSEMARIE TROCKEL. SELECTED DRAWINGS, OBJECTS, AND VIDEO WORKS 68 SIBYLLE BERGEMANN. PHOTOGRAPHS 72 SIGMAR POLKE. MUSIC FROM AN UNKNOWN SOURCE 76 THE EVENT OF A THREAD. GLOBAL NARRATIVES IN TEXTILES 80 TRAVELLING THE WORLD: ART FROM GERMANY 84 WITH/AGAINST THE FLOW. CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPHIC INTERVENTIONS #1 VIKTORIA BINSCHTOK #2 MICHAEL SCHÄFER 88 WITH/AGAINST THE FLOW. CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPHIC INTERVENTIONS #3 SEBASTIAN STUMPF #4 TAIYO ONORATO 92 WOLFGANG TILLMANS: FRAGILE 96 LEAP IN TIME. ERICH SALOMON. BARBARA KLEMM 100 NEW ARTISTS IN DIGITAL CONVERSATION 104 COLOPHON 111 Installation view Planbude Hamburg, Esso Häuser Requiem, Kunstraum Bethanien/Kreuzberg, Berlin, 2018, photo: Simone Gilges, © ifa CURATORIAL TEAM Anh-Linh Ngo Mirko Gatti Christian Hiller Max Kaldenhoff i f a T R A Christine Rüb – V Elke aus dem Moore 1 E Stefan Gruber 2 L 0 RESEARCH PARTNERS L 2 I School of Architecture, N Carnegie Mellon University E Pittsburgh, and TU Berlin, G D Institute for Architecture, I Prof. -

Codice A2001A D.D. 23 Ottobre 2017, N. 505 Convenzione Tra La Regione

REGIONE PIEMONTE BU45 09/11/2017 Codice A2001A D.D. 23 ottobre 2017, n. 505 Convenzione tra la Regione Piemonte e la Fondazione Torino Musei di Torino per l'affidamento dei beni di proprieta' regionale, provenienti dalle collezioni della Fondazione Italiana per la Fotografia, destinati alla Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Torino. (omissis) IL DIRIGENTE (omissis) determina di stipulare, per le motivazioni illustrate in premessa, tra la Regione Piemonte, Direzione Promozione della Cultura, del Turismo e dello Sport, rappresentata dal proprio Direttore, e la Fondazione Torino Musei, rappresentata dal proprio rappresentante legale, la convenzione il cui schema è allegato alla presente determinazione per farne parte integrante e sostanziale (Allegato A), che definisce le condizioni alle quali i beni elencati nell’Allegato 1 sono affidati alla stessa Fondazione. Resta facoltà della Regione Piemonte accedere ai beni affidati, in qualsiasi momento e circostanza, ove si renda necessario per finalità proprie, e a disporre degli stessi, previi specifici accordi con la Fondazione Torino Musei, per attività espositive e di valorizzazione promosse o sostenute dalla Regione medesima. La presente determinazione non prevede alcun onere finanziario a carico della Regione Piemonte. La presente determinazione sarà pubblicata sul B.U. della Regione Piemonte ai sensi dell’art. 61 dello Statuto e dell'art. 5 della legge regionale 12 ottobre 2010, n. 22 “Istituzione del Bollettino Ufficiale telematico della Regione Piemonte”. Avverso la presente determinazione è ammesso il ricorso straordinario al Presidente della Repubblica ovvero ricorso giurisdizionale innanzi al TAR rispettivamente entro 120 o 60 giorni dalla data di piena conoscenza del provvedimento amministrativo. -

Das Fotografische Tableau Als Form Der Entzeitlichung in Der Fotografischen Praxis Dieter Appelts

Dauer und Simultaneität: Das fotografische Tableau als Form der Entzeitlichung in der fotografischen Praxis Dieter Appelts Ann Kristin Krahn, Braunschweig Zeit, Raum und Bewegung in der Fotografie der europäischen Avantgarden Keine Frage ist von den Philosophen stärker vernachlässigt worden als die nach der Zeit; und dennoch sind sich alle darin einig, sie für grundlegend zu erklären. Dabei stellen sie zunächst Raum und Zeit auf dieselbe Ebene; […] Auf diese Weise errei- chen wir aber nichts. Die Analogie zwischen Zeit und Raum ist im Grunde genom- men ganz äußerlich und oberflächlich. […] Wenn wir uns also ihr zuwenden, wenn wir für die Zeit Eigenschaften suchen wie die des Raumes, dann bleiben wir beim Raum stehen, beim Raum, der die Zeit verdeckt und der sie unseren Augen bequem darstellt: Wir stoßen nicht bis zur Zeit selbst vor.1 Im historischen Kontext von Henri Bergsons Feststellung aus dem Jahr 1922 und gerade wieder in den letzten Jahrzehnten hat das The- ma der Darstellung von Zeit und Raum Anlass zu intensiven Ausein- andersetzungen gegeben, in der Philosophie und den Wissenschaften ebenso wie in den Künsten.2 Im Sinne der von Bergson angedeuteten problematischen Parallelisierung von Raum und Zeit wird im 20. Jahrhundert jedoch gerade das Modell der Raum-Zeit virulent, der zeitlichen Dimension als vierter Dimension innerhalb der des Raumes, welche mit der breiten Anerkennung der 1905 formulierten Relativi- tätstheorie von Albert Einstein einherging.3 1 Bergson 2014 (Erstauflage: 1922), 67. 2 Vgl. etwa Meyer 1964; Baudson 1985; Paflik 1987; Pochat 1996; Museum Fridericianum 1999; Kisser 2011; Becker – Cuntz – Wetzel 2011; Alloa 2013. 3 Vgl. Baudson 1985, 7. -

Travelling the World 11.10 – 8.12.2019

Изкуство от Германия Произведения от колекцията на ifa от 1949 г. до днес TRAVELLING THE WORLD Art from Germany Artworks from the ifa Collection 1949 to the Present 11.10 – 8.12.2019 Герхард Алтенбург Роден г. в Рьодихен-Шнепфентал Починал г. в Майсен След войната Алтенбург започва да взема уроци по рисуване и от г. следва в Универ- ситета Баухаус – Ваймар. Но след критики за „аморалност на неговите мотиви“ още през г. му се налага да напусне университета. През г. е първата му самостоятелна изложба в Берлин, през г. взема участие в documenta II и през г. – в documenta . Тъй като Алтенбург последователно се противопоставя на културната политика на ГДР, художественото му творчество бива ограничено, но това не пречи на признаването му – както в Източна, така и в Западна Германия. Рисунките и печатните графики на Алтенбург възникват от диалога с класическия модер- низъм и с изкуството на неговите съвременници, с литературата, философията, психо- логията, историята и естествените науки, както и с тюрингската природа, сред която живее, а също и от едно странно безвремие във възприемането на реалността. Работите му разкриват поетично-игриви, загадъчни и сюрреалистични светове на образи и мисли. Рисунката „Г-н старши правителствен съветник Байнес“ от 1949 г. показва мъжа, който се опитва да пречи на артистичното развитие на Алтенбург. Той го рисува като чудовищно насекомо, с пронизващи очи, хитлеров мустак и остър, кълвящ нос, с израстващи от раме- нете му нокти. Gerhard Altenbourg Born in Rödichen-Schnepfental Died in Meißen After the end of the war, Altenbourg took drawing classes and then, beginning in , studied at Bauhaus University in Weimar.