Bauhaus Guide Travel Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francia. Band 42

Francia. Forschungen zur westeuropäischen Geschichte Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris (Institut historique allemand) Band 42 (2015) Rezensionsexemplare/Livres recus pour recension DOI 10.11588/fr.2015.0.44728 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. Im Jahr 2014 eingegangene Rezensionsexemplare Livres reçus pour recension en 2014 Die Rezensionen werden online veröffentlicht. Les comptes rendus seront publiés en ligne. www.francia-online.net www.recensio.net Mittelalter/Moyen Âge – Amélia Aguiar Andrade, Adelaide Millán da Costa (Hg.), La ville médiévale en débat, Lissabon (Instituto de Estudos Medievais) 2013, 255 S. (Estudos, 8), ISBN 978-989-97066-9-9, EUR 25,00. – Antonella Ambrosio, Sébastien Barret, Georg Vogeler (Hg.), Digital diplomatics. The computer as a tool for the diplomatist?, Köln, Weimar, Wien (Böhlau) 2014, 347 S., 59 s/w, 21 farb. Abb. (Archiv für Diplomatik, Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde. Beiheft, 14), ISBN 978-3-412-22280-2, EUR 44,90. – Cristina Andenna, Gordon Blennemann, Klaus Herbers, Gert Melville (Hg.), Die Ord- nung der Kommunikation und die Kommunikation der Ordnungen. Band 2. Zentralität: Papsttum und Orden im Europa des 12. und 13. Jahrhunderts, Stuttgart (Franz Steiner Verlag) 2013, 331 S. -

The Bauhaus and Weimar Modernism

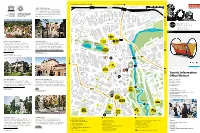

Buchenwald Memorial, Ettersburg Castle Sömmerda (B7 / B85) 100 m weimar UNESCO World Heritage 500 m Culture City of Europe The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar and Dessau have been on the UNESCO list of World Heritage since 1996. There are three objects in Weimar: the main building of the Bauhaus University Weimar, the former School of Applied Arts and the Haus Am Horn. Tiefurt Mansion deutschEnglish Harry-Graf-Kessler-Str. 10 5 Tiefurt Mansion Bauhaus-Universität Weimar Nietzsche Archive B Jorge-Semprùn-Platz a Oskar-Schlemmer-Str. d The building ensemble by Henry van de Velde was Friedrich Nietzsche spent the last years of his life at H e Stèphane- r 1 s revolutionary in terms of architecture at the turn of the “Villa Silberblick”. His sister established the Nietzsche Archive f Hessel-Platz e l d century. These Art School buildings became the venue here after his death and had the interior and furnishings e r S where the State Bauhaus was founded in 1919, making designed by Henry van de Velde. The current exhibition is t r a ß “Weimar” and the “Bauhaus” landmarks in the history of entitled “Kampf um Nietzsche” (“Dispute about Nietzsche”). e modern architecture. Humboldtstrasse 36 13 Mon, Wed to Sun 2pm – 5pm Geschwister-Scholl-Strasse 2 Mon to Fri 10am – 6pm | Sat & Sun 10am – 4pm Über dem Kegeltor C o u d r a y s t Erfurt (B7) r a ß e Berkaer Bahnhof 8 CRADLE, DESIGN: PETER KELER, 1922 © KLASSIK STIFTUNG WEIMAR 17 Jena (B7) 3 Tourist Information Office Weimar Haus Hohe Pappeln Weimar Municipal Museum 20 16 Markt 10, 99423 Weimar The Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, the artistic The permanent exhibition of the Municipal Museum presents Tel + 49 (0) 3643 745 0 advisor of the grand duchy, built this house for his family of “Democracy from Weimar. -

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Open Etoth Dissertation Corrected.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The College of Arts and Architecture FROM ACTIVISM TO KIETISM: MODERIST SPACES I HUGARIA ART, 1918-1930 BUDAPEST – VIEA – BERLI A Dissertation in Art History by Edit Tóth © 2010 Edit Tóth Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Edit Tóth was reviewed and approved* by the following: Nancy Locke Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Craig Zabel Head of the Department of Art History Michael Bernhard Associate Professor of Political Science *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT From Activism to Kinetism: Modernist Spaces in Hungarian Art, 1918-1930. Budapest – Vienna – Berlin investigates modernist art created in Central Europe of that period, as it responded to the shock effects of modernity. In this endeavor it takes artists directly or indirectly associated with the MA (“Today,” 1916-1925) Hungarian artistic and literary circle and periodical as paradigmatic of this response. From the loose association of artists and literary men, connected more by their ideas than by a distinct style, I single out works by Lajos Kassák – writer, poet, artist, editor, and the main mover and guiding star of MA , – the painter Sándor Bortnyik, the polymath László Moholy- Nagy, and the designer Marcel Breuer. This exclusive selection is based on a particular agenda. First, it considers how the failure of a revolutionary reorganization of society during the Hungarian Soviet Republic (April 23 – August 1, 1919) at the end of World War I prompted the Hungarian Activists to reassess their lofty political ideals in exile and make compromises if they wanted to remain in the vanguard of modernity. -

County Executive George Latimer

The june 2020 vol. 16 - issue 6 Shoreline Publishing Westchester’s Community Newspapers thebronxvillebulletin.com 914-738-7869 • shorelinepub.com COMPLIMENTARY ISSUE! Bulletin SeniorBronxville Car Parade Honors Graduates Senior Sabrina Mellinghoff Named National Merit Scholarship Winner Bronxville High School senior Sabrina Mellinghoff has been named a winner in this year’s 2020 Nation- The Bronxville Class of 2020 was recently celebrated by al Merit Scholarship Program com- way of a car parade through Bronxville. Teachers, family and petition. She is among an elite group friends were on hand to cheer them on. The parade traveled of students nationwide to receive a by NYPresbyterian Lawrence Hospital allowing students to $2,500 scholarship. wave signs of thanks to hospital staff. Congratulations to all Mellinghoff entered the academ- the students, parents and teachers!! ic competition as a junior, along with approximately 1.6 million students nationwide, by taking the Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qual- ifying Test that served as an initial screen of entrants. Students with the Sabrina Mellinghoff highest scores were chosen to advance to the semifinals before the pool was further narrowed down. Mellinghoff was selected as one of 7,500 winners from a group of more than 15,000 distinguished finalists. According to its website, the National Merit Scholarship Program honors students who show exceptional academic abil- ity and potential for success in rigorous college studies. 5 Orchard Place, Bronxville Village Kathleen Collins Licensed Associate RE Broker | 914.715.6052 [email protected] Bronxville Brokerage | 2 Park Place | 914.620.8682 | juliabfee.com Each Office is Independently Owned and Operated. -

Decision Taken in Closed Architectural Competition for the Bauhaus- Archiv / Museum Für Gestaltung, Berlin Berlin, 23 October 2015

Press release Decision taken in closed architectural competition for the Bauhaus- Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung, Berlin Berlin, 23 October 2015. The winner of the closed competition for the ‘Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum for Gestaltung, Berlin’, announced in June 2015 by the Senate Administration for Urban Develop- ment and the Environment, has been decided following a two-day meeting of the jury on 21 and 22 October 2015. The jury has awarded the first prize to the design submitted by Berlin architect Volker Staab and has recommended that the design should be implemented. Senate Director of Urban Development Regula Lüscher: ‘Volker Staab has given us a design that will cause a sensation. It has an attractively modest quality and it will complete the landscape ensemble of the Villa von der Heydt and the Walter Gropius building. An open, flexible museum setting will be created that upholds the experimentational quality of the Bauhaus idea. It will attract people to meet up there, exchange views and rediscover the many different aspects of the Bauhaus idea. A lantern shining in the night will be created, a glittering gem on the new square with a view opening onto the Landwehrkanal. The lower-lying courtyard will form the heart of the complex, enabling the existing building to enter into dialogue with the new one.’ The Minister of State for Culture, Monika Grütters, comments on the result: ‘I am delighted that Volker Staab, who already has an established reputation in the field of museum architecture – in Bayreuth and Münster, for example – has now presented a convincing design for Berlin as well. -

Museums Castles Gardens the Weimar Cosmos

Opening Times and Prices TOURS Winter Summer Adults Reduced Pupils Goethe National Museum Museums and historical sites MTWTFSS starts on last starts on last 16 – 20 years Tour 1: A Sunday in October Sunday in March Goethe and Classical Weimar with the Goethe Residence MUSEUMS Bauhaus-Museum Weimar* 10.00 am – 2.30 pm 10.00 am – 2.30 pm € 11.00 € 7.00 € 3.50 5 min. Goethe National Museum, Wittumspalais, 10.00 am – 6.00 pm 10.00 am – 6.00 pm € 11.00 € 7.00 € 3.50 Park on the Ilm and the Goethe Gartenhaus B Wittumspalais Ducal Vault 10.00 am – 4.00 pm 10.00 am – 6.00 pm € 4.50 € 3.50 € 1.50 All year round CASTLES Duration: 5 hours, distance: ca. 1,5 km Goethe Gartenhaus 10.00 am – 4.00 pm 10.00 am – 6.00 pm € 6.50 € 5.00 € 2.50 8 min. Cost: Price of admission to the respective museums Tip: Goethe National Museum 9.30 am – 4.00 pm 9.30 am – 6.00 pm € 12.50 € 9.00 € 4.00 Park on 10 min. Goethe- und The exhibition “Flood of Life – Storm of Deeds” reveals how C GARDENS Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv 8.30 am – 6.00 pm 8.30 am – 6.00 pm free modern Goethe’s ideas still are today. We recommend planning the Ilm Schiller-Archiv Opening times vary at the following at least two hours for your visit to the Goethe Residence where weekends: 12/13 Jan; 13/14 Apr; 11.00 am – 6.00 pm 10.00 am – 4.00 pm free 8 min. -

Bauhaus Centenary Year May Be Over, but the Influential Art and Design Movement Remains in the International Spotlight

Dear Journalist/Editor The Bauhaus centenary year may be over, but the influential art and design movement remains in the international spotlight. Below is an article that in- cludes comments from eminent publications, pointing out that 2019 was a cat- alyst for a new appreciation of the Bauhaus movement. And that interest con- tinues in 2020. Inspired by exhibitions both in Germany and around the world, more and more visitors are planning vacations in BauhausLand, the German federal states of Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. This editorial contribution is, of course, free for use. Bauhaus: Still in the spotlight! BAUHAUSLAND: ATTRACTING NEW FANS In 2019, the worldwide celebrations for the centenary of the Bauhaus focused on the achievements of this influential art and design movement. The range of exhibitions appealed to aficionados, but they also attracted a brand-new audi- ence. Leila Stone wrote in The Architect’s Newspaper: “Bauhaus is architec- ture. Bauhaus is costume design. Bauhaus is textile design. Bauhaus is furni- ture…it has never been more clear that Bauhaus is everywhere.” With appre- ciation increasing, more and more fans are planning to visit BauhausLand www.gobauhaus.com to spend their 2020 vacations in the German federal states of Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia. BAUHAUSLAND: THE HOT DESTINATION FOR 2020 GQ Magazine trumpeted the headline: “Why travel trendsetters are heading for the birthplace of Bauhaus.” The list of ‘must dos’ includes the striking new Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, where the ‘must sees’ range from Josef Albers’ ground-breaking Nesting Tables to Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s Glass Table Lamp, which is still manufactured today! As for Architectural Digest, it names the brand-new Bauhaus Museum Dessau as one of its “Top 20 Places to Travel in 2020,” adding that “If you decide to go on a Bauhaus-themed pilgrimage, be sure to visit the Meisterhäuser, a group of white cubist homes where Gropius, Kandinsky, and other Bauhaus luminaries lived.” TourComm Germany Olbrichtstr. -

Museen Schlösser Gärten Museen Schlösser Gärten

ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN UND PREISE TOUREN Winter Sommer Erwachsene ermäßigt Schüler Goethe-Nationalmuseum Einrichtungen M D M D F S S ab dem letzten ab dem letzten 16 – 20 Jahre Tour 1 A Sonntag im Oktober Sonntag im März Goethe und das Klassische Weimar mit Goethes Wohnhaus MUSEEN 5 min. MUSEEN Bauhaus-Museum Weimar 9.30 – 18 9.30 – 18 10 € 7 € 3,50 € GoetheNationalmuseum, Wittumspalais, Fürstengruft 10 – 16 10 – 18 4,50 € 3,50 € 1,50 € Park an der Ilm und Goethes Gartenhaus B Wittumspalais Goethes Gartenhaus 10 – 16 10 – 18 6,50 € 5 € 2,50 € Ganzjährig SCHLÖSSER 8 min. SCHLÖSSER Dauer: 5 Stunden, Strecke: ca. 1,5 km TIPP Goethe-Nationalmuseum 9.30 – 16 9.30 – 18 12,50 € 9 € 4 € Kosten: jeweiliger Museumseintritt Park an 10 min. Goethe- und Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv 8.30 – 18 8.30 – 18 frei C der Ilm Schiller-Archiv GÄRTEN Dass Goethe noch immer aktuell ist, zeigt die Ausstellung An folgenden Wochenenden geschlossen GÄRTEN 4./5. Jan, 11./12. Jan, 18./19. Jan, 25./26. Jan, 11 – 16 11 – 16 frei „Lebensfl uten – Tatensturm“, für die Sie zusammen mit der 8 min. 1./2. Feb, 8./9. Feb, 20./21. Jun Besichtigung von Goethes Wohn haus mindestens zwei Stunden Goethes Haus Am Horn 10 – 16 10 – 18 4,50 € 3,50 € 1,50 € einplanen sollten. Das Wittumspalais, in dem die verwitwete Herzogin D Gartenhaus Haus Hohe Pappeln 10 – 16 10 – 18 4,50 € 3,50 € 1,50 € Anna Amalia bis zu ihrem Tod lebte, ist heute ein Geheimtipp für Tou risten, die die adlige Wohnkultur erleben möchten. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einführung

Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einführung........................................................................................... 9 2 Anfänge.................................................................................................19 2.1 Herkunft, Jugend, Ausbildung...........................................................................19 2.2 Einstieg in den Beruf.........................................................................................22 3 Anfänge im Umfeld des Bauhauses Weimar und Dessau.................25 3.1 Im Bauatelier bei Walter Gropius und Adolf Meyer, 1919-20...................... 25 3.2 Unterricht bei Johannes Itten.......................................................................... 29 3.2.1 Spanienreise mit Paul Linder und Kurt Löwengard, Herbst 1920-21 - Begegnung mit Antoni Gaudi........................................................................32 3.3 Bekanntschaft mit Comelis van Eesteren, Jena 1922 .....................................40 4 Anfänge der Normungsbestrebungen................................................45 4.1 Maßtoleranzen und Präzision............................................................................45 4.2 Vorfertigung, Serienbau, Typisierung - Die Architekturausstellung des Bau büros Gropius 1922 und die Internationale Bauhausausstellung................. 1923 48 4.3 Carl Benscheidt sen. - „Der Mensch als Maß aller Dinge".........................59 4.4 Aufenthalt in Alfeld 1923-24 - Bekanntschaft mit Carl Benscheidt sen. und Karl Benscheidt jun. - Serienproduktion -

The Analysis of the Influence and Inspiration of the Bauhaus on Contemporary Design and Education

Engineering, 2013, 5, 323-328 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/eng.2013.54044 Published Online April 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/eng) The Analysis of the Influence and Inspiration of the Bauhaus on Contemporary Design and Education Wenwen Chen1*, Zhuozuo He2 1Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai, China 2Zhongyuan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, China Email: *[email protected] Received October 11, 2012; revised February 24, 2013; accepted March 2, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Wenwen Chen, Zhuozuo He. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The Bauhaus, one of the most prestigious colleges of fine arts, was founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius. Although it is closed in the last century, its influence is still manifested in design industries now and will continue to spread its principles to designers and artists. Even, it has a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, fashion design and design education. Up until now, Bauhaus ideal has al- ways been a controversial focus that plays a crucial role in the field of design. Not only emphasizing function but also reflecting the human-oriented idea could be the greatest progress on modern design and manufacturing. Even more, harmonizing the relationship between nature and human is the ultimate goal for all the designers to create their artworks. This essay will analyze Bauhaus’s influence on modern design and manufacturing in terms of technology, architecture and design education. -

Frankfurt Rhine-Ruhr Metropole Berlin 2012

Frankfurt Rhine-Ruhr Metropole Berlin 2012 SATURDAY ICAM 16 CONFERENCE IS HOSTED BY: SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAm) Schaumainkai 43, 60596 Frankfurt Tel: +49 (0)69 212 36 706; Fax: +49 (0)69 212 36 386 www.dam-online.de Peter Cachola Schmal, Director [email protected]; mobile: +49 (0)170 85 95 840 Wolfgang Voigt, Deputy Director [email protected]; mobile: +49 (0)162 61 65 677 Inge Wolf, Head of Archive [email protected] Peter Körner [email protected]; mobile: +49 (0)177 78 88 869 MUseUM FÜR ArchitektUR Und INGenieUrkUnst NRW (m:Ai) Leithestraße 33, 45886 Gelsenkirchen Tel: +49 (0)209 92 57 80; Fax: +49 (0)209 31 98 111 www.mai-nrw.de Dr. ursula kleefisch-Jobst, Director [email protected]; mobile: +49 (0)177 58 60 210 Peter Köddermann, Project Managment [email protected]; mobile: +49 (0)177 58 60 211 Akademie Der künste (AdK) Pariser Platz 4, 10117 Berlin Tel: +49 (0)30 20 05 70; Fax: +49 (0)30 20 05 71 702 www.adk.de Dr. eva-maria Barkhofen, Head of Architectural Archive [email protected]; mobile: +49 (0)176 46 686 386 OFFICIAL TRAVEL AGENCY: AGentUR ZeitsprUNG Kokerei Zollverein, Tor 3, Arendahlswiese, 45141 Essen Tel: +49 (0)201 28 95 80; Fax: +49 (0)201 28 95 818 www.zeitsprung-agentur.de Contact person: Anne Brosk [email protected]; mobile: +49 (0)179 51 64 504 2 SATURDAY SEPTEMBER 1, 2012 PRE-CONFERENCE TOUR DAM 13.00 – 17.00 REGISTRATION / MARKET PLACE 14.00 DEPARTURE BY BUS FROM THE DAM 14.20 – 15.30 FARBWERKE HOECHST ADMINISTRATION BUILDING by Peter Behrens, 1920 – 1924 With bridge and tower, the former administration building of the Hoechst AG is a master piece of expressionist architecture.