Appropriation & Attribution Questions for Classroom Discussions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![ISSUE 31 | AUGUST 2-8, 2018 | FREE [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI AUGUST 2-8, 2018 AUGUST 2-8 2018 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] Alibi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1208/issue-31-august-2-8-2018-free-2-weekly-alibi-august-2-8-2018-august-2-8-2018-weekly-alibi-3-alibi-1811208.webp)

ISSUE 31 | AUGUST 2-8, 2018 | FREE [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI AUGUST 2-8, 2018 AUGUST 2-8 2018 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] Alibi

GOOD OL’ FASHIONED CYNICISM SINCE 1992 PHOTO BY ERIC WILLIAMS PHOTOGRAPHY VOLUME 27 | ISSUE 31 | AUGUST 2-8, 2018 | FREE [ 2] WEEKLY ALIBI AUGUST 2-8, 2018 AUGUST 2-8 2018 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 27 | ISSUE 31 | AUGUST 2-8, 2018 EDITORIAL MANAGING AND FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC AND NEWS EDITOR: August March (ext. 245) [email protected] ARTS AND LIT.EDITOR: Maggie Grimason (ext. 239) [email protected] FOOD EDITOR: Robin Babb [email protected] COPY EDITOR: Taylor Grabowsky [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR: Ashli Mayo [email protected] STAFF WRITER: Joshua Lee (ext. 243) [email protected] SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR: Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] EDITORIAL INTERN: Adam Wood [email protected] CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Rob Brezsny, Carolyn Carlson, Desmond Fox, Taylor Grabowsky, Hosho McCreesh, Mayo Lua de Frenchie, Adam Wood PRODUCTION PRODUCTION MANAGER/EDITORIAL DESIGNER: Valerie Serna (ext. 254) [email protected] GRAPHIC DESIGNERS: Corey Yazzie [email protected] Ramona Chavez [email protected] STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER: Eric Williams [email protected] CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS: Max Cannon, Michael Ellis, Ryan North, Mike Organisciak, Jen Sorensen SALES SALES DIRECTOR: Tierna Unruh-Enos (ext. 248) [email protected] ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES: Kittie Blackwell (ext. 224) [email protected] John Hankinson (ext. 235) [email protected] Shane Boyd (ext. 223) [email protected] Sarah Shipman (ext. 210) [email protected] STREET TEAM: Alexis Al Omari [email protected] ADMINISTRATION PUBLISHER: Constance Moss (ext. 222) [email protected] CONTROLLER: Courtney Foster (ext. 257) [email protected] SYSTEMS MANAGER: Kyle Silfer (ext. 242) [email protected] WEB MONKEY: John Millington (ext. -

NEW RELEASE Cds 29/11/19

NEW RELEASE CDs 29/11/19 ADWAITH Melyn[Libertino]£9.99 THE KEYS Bring Me The Head Of Jerry Garcia[Libertino]£9.99 TIM BURGESS & BOB STANLEY PRESENT / VARIOUS ARTISTS Tim Peaks: Songs For A Late Night Diner[Ace] £9.99 *Signed postcards from Bob & Tim, while stocks last! * ALFFA Rhyddid O’r Gysgodion Gwenwynig[Recordiau Cosh]£9.99First Welsh Band To Hit One Million Spotify Plays! ANNE MÜLLER Heliopause[Erased Tapes]£11.99 BEANS ON TOAST The Inevitable Train Wreck£9.99Collaborative Project With Kitty Durham Of Kitty, Daisy & Lewis BLOOD INCANTATION Hidden History Of The Human Race[Century Media]£12.99 DOON KANDA Labyrinth [Hyperdub]£10.99Visual Artist And Musician Widely Known For His Modern Gothic Surrealist Art, Especially His Work With Björk, Arca, And Fka Twigs EMILY BARKER Shadow Box£9.99 FLYING COLORS Third Degree£12.99 FRIZBEEY 4 Albym[4CD Set]£9.99 JACK PEÑATE After You[XL Recordings]£9.99 JESPER LINDELL (Blues Pills) Everyday Dreams[Alive]£9.99 JOHN DENVER & THE MUPPETS A Christmas Together £9.99 JOSEPHINE FOSTER & The Supposed All The Leaves Are Gone [Fire]£9.99 MARCONI UNION Dead Air£9.99 MICK RONSON Only After Dark: The Complete Mainman Recordings[4CD Set on Cherry Red]£21.99Famously Played On A Number Of David Bowie Albums! RICK WAKEMAN (Yes Christmas Portraits£9.99 SCORN Café Mor Feat. Jason Williamson of Sleaford Mods £9.99 SIMPLY RED Blue Eyed Soul[Deluxe 2CD]£14.99 SNOOP DOGG I Wanna Thank Me£9.99 SOME BODIES Sunscreen£9.99 STICK IN THE WHEEL Against The Loathsome Beyond Mixtape£7.99 THE FLAMING LIPS Feat. -

Flaming Lips'

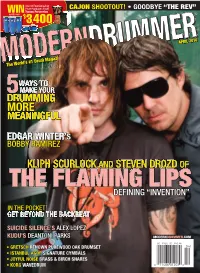

WILL CALHOUN’S DRUMSET $ WIN VALUED OVER 5,900 PINK’S MARK SCHULMAN GEARS UP MODERNTHE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE DRUMMERNOVEMBER 2013 FLAMING LIPS’ DROZD AND SCURLOCK LIGHT OUR FIRE AGAIN ILAN RUBIN HOT PARAMORE AND 10 NEW REGIME BEATS ’SREAL-DEAL RAGER PREPARATION, MEET OPPORTUNITY MODERNDRUMMER.com + TONY THOMPSON’s POWER STATION + IN THE STUDIO SPECIALTY MIC APPLICATIONS + KENNY WASHINGTON AND DAFNIS PRIETO ON BACKING SOLOISTS + REVIEWED: MAPEX SATURN IV MH EXOTIC KIT paiste.com THE NEW ALTERNATIVE FOR SIGNATURE PLAYERS Scan the QR Code to see Sutter Jason Vanderbilt, Franklin (pictured), Dean Butterworth and John Robinson demo the new Signature «Precision» series. The new Signature «Precision» series is created using Paiste’s proprietary Signature Alloy, and features the typical hallmarks of Paiste’s original Signature sound - brightness, fullness, strong presence and projection, with brilliant musicality. A particular quality of the Signature «Precision» is its clean and focused character in combination with a very articulate, straight-ahead sound. The goal for the Signature «Precision» was to create a more affordable Signature sound. Part of the success of this project is the incredible sound potency that already exists within the Signature Alloy. QUALITY HAND CRAFTED CYMBALS MADE IN SWITZERLAND • 830 Series Hardware • Demonator Bass Pedal • OptiLoc Tom Mounts • Blended Shell Construction • Exclusive Lifetime Warranty THE BEST SELLING DRUMSET OF ALL TIME. INTRODUCING THE ALL NEW EXPORT SERIES Welcome to Ground Zero for a legion of pro drummers. From Joey Jordison of Slipknot and Mike Wengren of Disturbed to Ray Luzier of Korn and Will Hunt of Evanescence, this is where it all began. -

Gig” “This Won’T TICKETS Be Just MONKEYSARCTICTO SEE

Gruff Rhys Pete Doherty Wolf Alice SECRET ALBUM DETAILS! Tune-Yards “I’ve been told not to tell but…” 24 MAY 2014 MAY 24 The Streets IAN BROWN IAN “This won’t Arctic be just another gig” Monkeys “It’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at...” on their biggest weekend yet and what lies beyond ***R U going to be down the front?*** Interviews with the stellar Finsbury Park line-up Miles Kane Tame Impala Royal Blood The Amazing Snakeheads TICKETS TO SEE On the town with Arctics’ THE PAST, PRESENT favourite new band ARCTIC & FUTURE OF MUSIC WIN 24 MAY 2014 | £2.50 HEADLINE US$8.50 | ES€3.90 | CN$6.99 MONKEYS BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME14021105.pgs 16.05.2014 12:29 BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME14018164.pgs 25.04.2014 13:55 ESSENTIAL TRACKS NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 24 MAY 2014 4 SOUNDING OFF 8 THE WEEK THIS WEEK 16 IN THE STUDIO Pulled Apart By Horses 17 ANATOMY OF AN ALBUM The Streets – WE ASK… ‘A Grand Don’t Come For Free’ NEW 19 SOUNDTRACK OF MY LIFE Anton Newcombe, The Brian Jonestown Massacre BANDS TO DISCOVER 24 REVIEWS 40 NME GUIDE → THE BAND LIST 65 THIS WEEK IN… Alice Cooper 29 Lykke Li 6, 37 Anna Calvi 7 Lyves 21 66 THINK TANK The Amazing Mac Miller 6 Snakeheads 52 Manic Street Arctic Monkeys 44 Preachers 7 HOW’s PETE SPENDING Art Trip And The Michael Jackson 28 ▼FEATURES Static Sound 21 Miles Kane 50 Benjamin Booker 20 Mona & Maria 21 HIS TIME BEFORE THE Blaenavon 32 Morrissey 6 Bo Ningen 33 Mythhs 22 The Brian Jonestown Nick Cave 7 Massacre 19 Nihilismus 21 LIBS’ COMEBACK? Chance The Rapper 7 Oliver Wilde 37 Charli XCX 32 Owen Pallett 27 He’s putting together a solo Chelsea Wolfe 21 Palm Honey 22 8 Cheerleader 7 Peace 32 record in Hamburg Clap Your Hands Phoria 22 Say Yeah 7 Poliça 6 The Coral 15 Pulled Apart By 3 Courtly Love 22 Horses 16 IS THERE FINALLY Courtney Barnett 31 Ratking 33 Arctic Monkeys Courtney Love 36 Rhodes 6 Barry Nicolson gets the skinny Cymbals Eat Guitars 7 Royal Blood 51 A GOOD Darlia 40 Röyksopp & Robyn 27 on their upcoming Finsbury Echo & The San Mei 22 Park shows. -

Drumming More Meaningful

One Of Four Amazing Prize Packages From CAJON SHOOTOUT! • GOODBYE “THE REV” WIN Tycoon Percussion worth over $ 3,400 APRIL 2010 The World’s #1 Drum Magazine WAYS TO 5MAKE YOUR DRUMMING MORE MEANINGFUL EDGAR WINTER’S BOBBY RAMIREZ KLIPH SCURLOCK AND STEVEN DROZD OF THE FLAMING LIPS DEFINING “INVENTION” IN THE POCKET GET BEYOND THE BACKBEAT SUICIDE SILENCE’S ALEX LOPEZ KUDU’S DEANTONI PARKS MODERNDRUMMER.COM • GRETSCH RENOWN PUREWOOD OAK DRUMSET • ISTANBUL AGOP SIGNATURE CYMBALS • JOYFUL NOISE BRASS & BIRCH SNARES • KORG WAVEDRUM April2010_Cover.indd 1 1/22/10 10:38:19 AM CONTENTS Volume 34, Number 4 • Cover photo by Timothy Herzog Timothy Herzog Paul La Raia 58 46 42 FEATURES 42 SUICIDE SILENCE’S ALEX LOPEZ 14 UPDATE TESLA’S Over-the-top rock? Minimalist metal? Who cares what bag they put him in— TROY LUCCKETTA Suicide Silence’s drummer has chops, and he knows how to use ’em. ARK’S JOHN MACALUSO 46 THE FLAMING LIPS’ JACKYL’S CHRIS WORLEY 16 GIMME 10! KLIPH SCURLOCK AND STEVEN DROZD BOBBY SANABRIA The unfamiliar beats and tones of the Lips’ trailblazing new studio album, Embryonic, were born from double-drummer experiments conducted in an empty house. How the 36 SLIGHTLY OFFBEAT timekeepers in rock’s most exploratory band define invention. ERIC FISCHER 38 A DIFFERENT VIEW 58 KUDU’S DEANTONI PARKS PETER CASE Once known as a drum ’n’ bass pioneer, the rhythmic phenom is harder than ever to pigeonhole. But for sheer bluster, attitude, and uniqueness on the kit, look no further. 76 PORTRAITS MUTEMATH’S DARREN KING MD DIGITAL SUBSCRIBERS! When you see this icon, click on a shaded box on the MARK SHERMAN QUARTET’S TIM HORNER page to open the audio player. -

The Flaming Lips at the Christmason Mars Set in Early September

nWynethe' 1 Flaming L f Redefi ) Oklah4qmI Music . " Plus; rs with' HlKe ldf0~ tk,'ICi ss ~i~titiii~ain~*$ This 1 oklahornatc corn $.- - ~Upr-~,WByrnCaynr,ondMlchadMnr oklahomal&afChtirhnar &A- I -,y;km Christw Parade NOVEMBER 19THRUJANUARY 2 Lawton Fort Sill presents the Bouleva )f Liqhts Display enchantment of the holiday season with a variety of memory-making I events and performances. Bring a friend, bring your family, and enjoy all we have to offer during this special time of year. For a completelisting of events, maps and brochures come visit www.lawtonfortsillchamber.com u4CEMBER 2-4 Y- I Csmmu* re.mACharley's La 629 SW CAvenue Lawton, Oklahoma 73501 .580.355354 - SQO.d?+ % Supporting medical resea always been a no-braine making the decisio~l+" the Oklahoma Mdkdl fh Foundation has never Bee attractive. For every donaa make to OMRF, you'll eaq credit worth half that (up to a total credit of $1, It's simple-t give, the more you sabe. h NOVEMBER DECEMBER 2005 1 VOLUME 55, NUMBER 6 TODAY Onthe cover. In an exclusive !E Oklahoma Today shoot, OI5 J. Michelle Madn-Coyne photographedthe Flaming Lips at the Christmason Mars set in early September. I FEATURES A High Gloss Lip Service Red-Dirt Holidays Cenhrry City At the Gloss Mountain State By many accounts, the Who is this bright-eyed Oklahoma was never the same Park, one writer finds what Flaming Lips may be the youngster? Turn to page 46 after the 1905discovery of oil it means to return home and greatest band in the world, to find out which Oklahoma in northeastern Oklahoma. -

The Flaming Lips Embryonic Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Flaming Lips Embryonic mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Embryonic Country: US Released: 2009 Style: Psychedelic Rock, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1306 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1519 mb WMA version RAR size: 1333 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 656 Other Formats: WMA AHX WAV MP3 VOC VOX MP1 Tracklist A1 Convinced Of The Hex 3:57 A2 The Sparrow Looks Up At The Machine 4:14 A3 Evil 5:38 A4 Aquarius Sabotage 2:10 B1 See The Leaves 4:24 B2 If 2:05 B3 Gemini Syringes 3:41 B4 Your Bats 2:35 B5 Powerless 6:57 C1 The Ego's Last Stand 5:40 C2 I Can Be A Frog 2:14 C3 Sagittarius Silver Announcement 2:59 C4 Worm Mountain 5:22 C5 Scorpio Sword 2:02 D1 The Impulse 3:30 D2 Silver Trembling Hands 3:59 D3 Virgo Self-Esteem Broadcast 3:44 D4 Watching The Planets 5:17 Credits Artwork By [Design & Layout] – George Salisbury Who Is Particle? Engineer – Dave Fridmann Engineer [Additional] – Michael Ivins Mastered By – Dave Fridmann Mixed By – Dave Fridmann, The Flaming Lips Music By, Songwriter – The Flaming Lips Performer – Kliph Scurlock, Michael Ivins, Steven Drozd, Wayne Coyne Performer [Additional Singing & Playing] – MGMT (tracks: C4) Performer [Additional Singing, Screaming, Animal Sounds And Noises] – Karen O (tracks: B3, C2, D4) Producer – Dave Fridmann, Scott Booker, The Flaming Lips Programmed By – Dave Fridmann Recorded By – Dave Fridmann, The Flaming Lips Voice [Spoken Announcements] – Thorsten Möhrmann Notes The first song on side D "Scorpio Sword" was accidentally placed at the end of side C. -

Drummer's Journal's

Contents Masthead 08 Subterranean Rolling Stock Larry & Sonia Wright 20 The Art Of Self-Deprecation Kliph Scurlock of The Flaming Lips 33 More Than Fun And Games Robb Reiner and Lips of Anvil Win! 48 This Is Not a Wrap Keith Davidson of Premier Percussion 67 Technicalities Ben Martin A Call To Arms 70 Selective Colour CONTENTS A Conversation with Fay Milton of Savages Issue Four, August 2013 79 Artefacts Carl Palmer, Premier and Chrome Plating We’ve made the magazine easier to navigate, and the contents page is now fully interactive. You can click the title of any article to skip straight to it. You can also click on any of The Support Drummer’s Journal’s logos throughout the magazine to return to the contents page. 83 The Man With The Golden Arms If you’re viewing in full screen mode, which we’d heartily recommend, you can use your Ben Reimer keyboard’s arrow keys to access the next or previous page. Ads are clickable too, so if you see something you like, you can click it for more information. Subscriptions/Newsletter Editor: Tom Hoare [email protected] Creative: Luke Douglas [email protected] Technical: Andrew Jones Creative Consultant: Flora Hodson Contributors: Ben Martin, Nick Hopkin, Dan Stadnicki, Julia Kaye, Dalila Kriheli, Michael J Fajardo, Antoine Carlier, Kris Krug, Rob Wheatley. Thanks: Caitlin Reeves, Karen Whitlam, Elaine Smith, Mike Thomas, Patrick Johnson, John Wilkinson, John Best, Florian Leroy-Alcantara, Kate Darracott, Greg And Julia. Special Mentions: David Kirby and Michael Noyd. Cover: Veneers MASTHEAD www Issue Four, August 2013 Copyright © The Drummer’s Journal 2013 The proprietors and contributors to The Drummer’s Journal have asserted their right under the Copyright Designs and Patens Act 1988 to be identified as the owners and authors of this work. -

Appropriation & Attribution Questions for Classroom Discussions

Appropriation & Attribution Questions for classroom discussions 1) What is the relationship between attribution and appropriation? How are they similar? How are they different? 2) The video acknowledges that artistic progress may not be possible without incorporating important developments from the past. Do you agree? Why or why not? 3) How can artists use others’ creative works in an ethical manner? When is appropriation unethical? 4) Have you ever pirated or copied works protected by copyright? What harms did you cause? Do you feel you were ethically justified to do so? Why or why not? 5) Think of an example of something you consider to be a “rip-off” and something you think is an innovative repurposing of another’s work. What makes them different? Could your conclusions be shaped by your own interests? 6) Fair use is a doctrine that allows for limited use of copyrighted materials without acquiring permission, for purposes such as teaching, journalism, parody, or critique. Do you agree with these parameters? Are there other instances that should constitute fair use? 1 Case Study: Christina Fallin: “Appropriate Culturation?” In March 2014, twenty-seven year old Christina Fallin, daughter of Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin, found herself at the center of controversy when she posted an image of herself wearing a red Plains headdress on Facebook and Instagram with the tag “Appropriate Culturation.” Fallin posed for this photo as a promotional piece for her band, Pink Pony. Public outcry criticized Fallin for appropriating Native American cultures, sparking uproar on social media and leading to protests at their shows. In response, Fallin and Pink Pony removed the photo and released a statement on their Facebook page explaining their aesthetic appreciation for Native American culture. -

The Flaming Lips the Terror Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Flaming Lips The Terror mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: The Terror Country: Europe Released: 2013 Style: Indie Rock, Psychedelic Rock, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1612 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1358 mb WMA version RAR size: 1970 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 802 Other Formats: AAC MP2 DXD VQF TTA MOD MIDI Tracklist A1 Look…The Sun Rising 5:11 A2 Be Free, A Way 5:13 A3 Try To Explain 5:00 B1 You Lust 13:02 B2 The Terror 6:21 C1 You Are Alone 3:46 C2 Butterfly, How Long It Takes To Die 7:30 C3 Turning Violent 4:16 C4 Always There, In Our Hearts 4:34 D We Don't Control the Controls 14:36 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – The Flaming Lips Copyright (c) – The Flaming Lips Published By – BMG Platinum Songs Published By – Lovely Sorts Of Death Music Recorded At – Tarbox Road Studios Recorded At – Pink Floor Studios Engineered At – Pink Floor Studios Mixed At – Pink Floor Studios Credits Design, Layout – George Salisbury Engineer [Additional] – Michael Ivins Engineer [Additional], Recorded By [Additional], Mixed By [Additional] – Mack Hawkins Mastered By – Dave Fridmann Music By [Additional], Vocals [Additional] – Phantogram (tracks: 4) Music By, Performer – Derek Brown , Kliph Scurlock, Michael Ivins, Steven Drozd, Wayne Coyne Producer – Dave Fridmann, Scott Booker, The Flaming Lips Recorded By, Mixed By – Dave Fridmann, The Flaming Lips Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 6 02537 32476 7 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Warner Bros. The Flaming The Terror (CD, Records, Lovely 534627-2, none 534627-2, none US 2013 Lips Album) Sorts of Death Records Warner Bros. -

2017Spring Prasch.Pdf

Warner Brothers premiered Dodge City in the real Kansas town of that name on April 1, 1939. Activities included a parade, of course, that featured the film’s star Errol Flynn (mounted, right) and dozens of other cast members, along with tens of thousands of visitors and residents of the “Cowboy Capital.” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 40 (Spring 2017): 46-71 46 Kansas History The Place of the Present in the Past: Dichronicity in Recent Kansas/Plains Films Edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch rranging the films in this year’s selection of reviews (coming to you an issue earlier than usual because of the special issue devoted to the sesquicentennial of the Chisholm Trail this summer) presented an interesting quandary. Usually, it is a simple enough procedure: start with the classic films, then go in chronological order. But where, in that case, did Kevin Flanagan’s review of American Interior belong? On the one hand, the film was about John Evans, whose quixotic expedition in the 1790s to find the Welsh-speaking AIndians that he was convinced lived in the American interior (there is this legend about the twelfth-century Welsh Prince Madoc, see) took him deep into the Great Plains, as far as Mandan territory in the Dakotas. On the other hand, it was just as much, or more, about the quixotic expedition of the contemporary Welsh rocker Gruff Rhys, retracing the route of his distant ancestor in a series of concerts and conversations that reflected as often on contemporary issues and circumstances as they did on the eighteenth century. -

Audio + Video 4/27/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

New Releases WEA.CoM iSSUE 08 APRiL 27 + MAy 4, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word audio + video 4/27/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CD- B.o.B Presents: The ATL 518903 B.O.B Adventures of Bobby Ray $13.99 4/27/10 4/7/10 B.o.B Presents: The CD- Adventures of Bobby Ray ATL 524375 B.O.B (Amended) $13.99 4/27/10 4/7/10 REP A-523482 CLAPTON, ERIC Money & Cigarettes (Vinyl) $22.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 Billion Dollar Babies (180 RRW A-2685 COOPER, ALICE Gram Vinyl) $34.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 CD- TSG 25490 LONESTAR Party Heard Around the World $17.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 CD- CUR 79181 MESSINA, JO DEE Unmistakable Love $9.94 4/27/10 4/7/10 CD- LAT 524047 MAGO DE OZ Gaia III - Atlantia $20.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 CD- LAT 524445 MAGO DE OZ Gaia III - Atlantia (Amended) $20.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 CD- LAT 524398 MOENIA En Electrico $9.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 CD- LAT 524401 MOENIA En Electrico - Super 6 Tracks $6.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 DV- LAT 524400 MOENIA En Electrico (DVD) $14.99 4/27/10 3/31/10 CX- Clasicos Para La Bohemia LAT 524373 PESADO (CD/DVD) $14.98 4/27/10 3/31/10 TYLER, JONATHAN & THE CD- NORTHERN ATL 523005 LIGHTS Pardon Me $13.99 4/27/10 4/7/10 CD- Gloryland 2: Bluegrass Gospel TL 25482 VARIOUS ARTISTS Classics $14.98 4/27/10 4/7/10 Last Update: 03/21/10 ARTIST: B.o.B TITLE: B.o.B Presents: The Adventures Of Bobby Ray Label: ATL/Atlantic Config & Selection #: CD 518903 Street Date: 04/27/10 Order Due Date: 04/07/10 UPC: 075678966507 Box Count: 30 WEBSITES: Unit Per Set: 1 www.bobatl.com SRP: $13.99 Myspace Link Alphabetize Under: B Twitter Link File Under: Hip Hop YouTube Link For the latest up to date info on WEA.com OTHER EDITIONS: this release visit .