Economic and Social Cbiihcii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR) Monazamet El Seha El Alamia Street Extension of Abdel Razak El Sanhouri Street P.O

ISSN: 2071-2510 Vol. 11 No.2 For further information contact: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Knowledge Sharing and Production (KSP) Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR) Monazamet El Seha El Alamia Street Extension of Abdel Razak El Sanhouri Street P.O. Box 7608, Nasr City Cairo 11371, Egypt Tel: +20 2 22765047 IMEMR Current Contents Fax: +20 2 22765424 September 2017 e-mail: [email protected] Vol. 16 No. 3 Providing Access to Health Knowledge to Build a Healthy Future http://www.emro.who.int/information-resources/imemr/imemr.html Index Medicus for the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region with Abstracts IMEMR Current Contents September 2017 Vol. 16 No. 3 © World Health Organization 2017 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate borderlines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. -

And “Climate”. Qarah Dagh in Khorasan Ostan on the East of Iran 1

IRAN STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 1397 1. LAND AND CLIMATE Introduction T he statistical information that appeared in this of Tehran and south of Mazandaran and Gilan chapter includes “geographical characteristics and Ostans, Ala Dagh, Binalud, Hezar Masjed and administrative divisions” ,and “climate”. Qarah Dagh in Khorasan Ostan on the east of Iran 1. Geographical characteristics and aministrative and joins Hindu Kush mountains in Afghanistan. divisions The mountain ranges in the west, which have Iran comprises a land area of over 1.6 million extended from Ararat mountain to the north west square kilometers. It lies down on the southern half and the south east of the country, cover Sari Dash, of the northern temperate zone, between latitudes Chehel Cheshmeh, Panjeh Ali, Alvand, Bakhtiyari 25º 04' and 39º 46' north, and longitudes 44º 02' and mountains, Pish Kuh, Posht Kuh, Oshtoran Kuh and 63º 19' east. The land’s average height is over 1200 Zard Kuh which totally form Zagros ranges. The meters above seas level. The lowest place, located highest peak of this range is “Dena” with a 4409 m in Chaleh-ye-Loot, is only 56 meters high, while the height. highest point, Damavand peak in Alborz The southern mountain range stretches from Mountains, rises as high as 5610 meters. The land Khouzestan Ostan to Sistan & Baluchestan Ostan height at the southern coastal strip of the Caspian and joins Soleyman Mountains in Pakistan. The Sea is 28 meters lower than the open seas. mountain range includes Sepidar, Meymand, Iran is bounded by Turkmenistan, the Caspian Sea, Bashagard and Bam Posht Mountains. -

Country of Origin Information Report Somalia July 2008

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SOMALIA 30 JULY 2008 UK BORDER AGENCY COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 30 JULY 2008 SOMALIA Contents Preface LATEST NEWS EVENTS IN SOMALIA, FROM 4 JULY 2008 TO 30 JULY 2008 REPORTS ON SOMALIA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED SINCE 4 JULY 2008 Paragraphs Background Information GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................. 1.01 Maps .............................................................................................. 1.04 ECONOMY ................................................................................................. 2.01 Currency change, 2008 ................................................................ 2.06 Drought and famine, 2008 ........................................................... 2.10 Telecommunications.................................................................... 2.14 HISTORY ................................................................................................... 3.01 Collapse of central government and civil war ........................... 3.01 Peace initiatives 2000-2006 ......................................................... 3.14 ‘South West State of Somalia’ (Bay and Bakool) ...................... 3.19 ‘Puntland’ Regional Administration............................................ 3.20 The ‘Republic of Somaliland’ ...................................................... 3.21 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................... 4.01 CONSTITUTION ......................................................................................... -

"Disappearances" in the Philippines

May 1990 "DISAPPEARANCES" IN THE PHILIPPINES Johnny Salivo, an organizer for the National Federation of Sugar Workers in Negros Occidental, Philippines, disappeared on April 6, 1990 after being abducted by armed men believed linked to the Armed Forces of the Philippines. He is the fourteenth person to have been abducted by agents of the government this year. Seven persons remain missing and three others died while in military custody. Asia Watch is concerned by the growing number of disappearances throughout the Philippines, from rural areas of Bulacan Province to Manila. Most of the victims are members of labor, peasant, or urban poor organizations suspected by the military of being front organizations for the Communist Party of the Philippines or its armed wing, the New People's Army (NPA). Others are suspected NPA combatants of sympathizers. Asia Watch is calling on the Philippine government to conduct full and impartial investigations into all cases of disappearances and to bring those responsible to justice. It welcomes the invitation extended by the Philippines government to the United Nations Working Group on Disappearances in August 1989 to visit the Philippines and urges that everything possible be done to ensure that the visit takes place in 1990. Legal and Institutional Obstacles to Investigating Disappearances A person "disappears" when he or she is abducted or taken into custody by agents of the government who then refuse to acknowledge holding the person in question. Because of the severity of the problems of disappearances during the final years of the Marcos government, human rights lawyers and others made a concerted effort to get legal safeguards established by the Aquino administration which would prevent disappearances from taking place. -

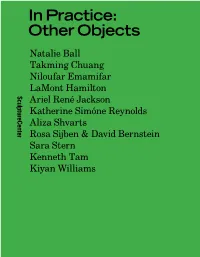

In Practice: Other Objects

In Practice: Other Objects Natalie Ball Takming Chuang Niloufar Emamifar LaMont Hamilton Ariel René Jackson Katherine Simóne Reynolds Aliza Shvarts Rosa Sijben & David Bernstein Sara Stern Kenneth Tam Kiyan Williams In Practice: Other Objects All rights reserved, including rights of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. © SculptureCenter and the authors Published by SculptureCenter 44-19 Purves Street Long Island City, NY 11101 +1 718 361 1750 [email protected] www.sculpture-center.org ISBN: 978-0-9998647-4-6 Design: Chris Wu, Yoon-Young Chai, and Ella Viscardi at Wkshps Copy Editor: Lucy Flint Printer: RMI Printing, New York All photographs by Kyle Knodell, 2019 unless otherwise noted. 2 SculptureCenter In Practice: Other Objects 3 Natalie Ball In Practice: With a foundation in visual archives, materiality, gesture, and historical research, I make art as proposals of refusal to complicate an easily affirmed Other Objects and consumed narrative and identity without absolutes. I am interested in examining internal and external discourses that shape American history and Indigenous identity to challenge historical discourses that have constructed a limited and inconsistent visual archive. Playing Dolls is a series of assemblage sculptures as Power Objects that are influenced by the paraphernalia and aesthetics of a common childhood activity. In Practice: Other Objects presents new work by eleven artists and artist teams Using sculptures and textile to create a space of reenactment, I explore modes who probe the slippages and interplay between objecthood and personhood. of refusal and unwillingness to line up with the many constructed mainstream From personal belongings to material evidence, sites of memory, and revisionist existences that currently misrepresent our past experiences and misinform fantasies, these artists isolate curious and ecstatic moments in which a body current expectations. -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Games of Truth in Chile´S University Entrance Exam Involving the Controversy Around the Occupation of the Palestine Territory by Israel

SEÇÃO: ARTIGOS Jogos de verdade no vestibular chileno na polêmica pela ocupação do território palestino por Israel María Paulina Castro Torres1 Resumo Com interesse em aprofundar a compreensão das provas estandardizadas de admissão universitária e com o objetivo de discutir as relações entre o vestibular e o currículo chileno, propomo-nos, neste artigo, a analisar uma polêmica suscitada por uma pergunta de história, geografia e ciências sociais que circulou na mídia digital do país no ano 2015. Com esse escopo, a partir da análise discursiva de Maingueneau, Grillo e Possenti, sustentaremos um diálogo teórico entre Bakhtin, Bourdieu e Foucault. Desse modo, focaremos nos comentários desenvolvidos por internautas em torno da verdade ou da falsidade de uma questão desse vestibular, a qual se refere à ocupação do território da Palestina por Israel. Além disso, para melhor apresentarmos nossa perspectiva analítica, tomaremos, da mesma disciplina da prova do ano 2012, o gabarito comentado de uma questão que faz referência à resistência indígena do povo mapuche à colonização dos espanhóis. Assim, a partir desse corpus, procederemos à descrição e à comparação das regras de formação discursiva desenvolvidas no que consideraremos um campo de possibilidades estratégicas que permite interesses irreconciliáveis. Afinal, não apenas discutiremos as relações de pressão e de legitimação entre as perguntas desse exame de admissão e o currículo chileno por competências, mas também trataremos da constituição dos candidatos como efeitos de poder e de saber, isto é, a constituição dos candidatos tidos então como competentes ou incompetentes no acesso à universidade. Palavras chave Vestibular chileno – Currículo – Discurso. 1- Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brasil. -

Official 2021 Neqas-Cc Participants As of July 13, 2021

OFFICIAL 2021 NEQAS-CC PARTICIPANTS AS OF JULY 13, 2021 REGION I ACCU HEALTH DIAGNOSTICS ACCURA-TECH DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY AGOO FAMILY HOSPITAL AGOO LA UNION MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER, INC. ALAMINOS CITY HEALTH OFFICE LABORATORY ALCALA MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE LABORATORY ALLIANCE DIAGNOSTIC CENTER APELLANES ADULT & PEDIATRIC CLINIC AND LABORATORY ASINGAN COMMUNITY HOSPITAL ASINGAN DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC BACNOTAN DISTRICT HOSPITAL BALAOAN DISTRICT HOSPITAL BANGUI DISTRICT HOSPITAL BANI-RHU CLINICAL LABORATORY BASISTA RURAL HEALTH UNIT LABORATORY BAYAMBANG DISTRICT HOSPITAL BETHANY HOSPITAL, INC. BETTERLIFE MEDICAL CLINIC BIO-RAD DIAGNOSTIC CENTER BIOTECHNICA DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY BLESSED FAMILY DOCTORS GENERAL HOSPITAL BLOOD CARE CLINICAL LABORATORY BOLINAO COMMUNITY HOSPITAL BRILLIANTMD LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER BUMANGLAG SPECIALTY HOSPITAL CABA DISTRICT HOSPITAL CABUGAO RHU LABORATORY CALASIAO DIAGNOSTIC CENTER CALASIAO MUNICIPAL CLINICAL LABORATORY CANDON GENERAL HOSPITAL CANDON ST. MARTIN DE PORRES HOSPITAL CANDON ST. MARTIN DE PORRES HOSPITAL (REGIONAL) CAOAYAN RHU CLINICAL LABORATORY CARDIO WELLNESS LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER CHRIST BEARER CLINICAL LABORATORY CICOSAT LABORATORY CIPRIANA COQUIA MEMORIAL DIALYSIS AND KIDNEY CENTER, INC. CITY GOVERNMENT OF BATAC CLINICAL LABORATORY CLINICA DE ARCHANGEL RAFAEL DEL ESPIRITU SANTO AND LABORATORY CORDERO DE ASIS CLINIC, X-RAY & LABORATORY OFFICIAL 2021 NEQAS-CC PARTICIPANTS AS OF JULY 13, 2021 CORPUZ CLINIC AND HOSPITAL CUISON HOSPITAL INCORPORATED DAGUPAN DOCTORS VILLAFLOR MEMORIAL HOSPITAL, INC. DASOL COMMUNITY HOSPITAL DDVMH-URDANETA DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY & X-RAY CLINIC DE GUZMAN CLINICAL LABORATORY DECENA GENERAL HOSPITAL DEL CARMEN MEDICAL CLINIC & HOSPITAL, INC. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH-DRUG TREATMENT AND REHABILITATION CENTER DAGUPAN CLINICAL LABORATORY SERVICES DINGRAS ACCU-PRIME CLINICAL LABORATORY DINGRAS DISTRICT HOSPITAL DIVINE MERCY FOUNDATION OF URDANETA HOSPITAL DOCTOR'S LINK CLINIC & LABORATORY DONA JOSEFA EDRALIN MARCOS DISTRICT HOSPITAL DR. -

Name: Seyyed Taghi Surname: Heidari Sex: Male Date Of

CURRICULUM OF VITAE Name: Seyyed Taghi Surname: Heydari Sex: Male Date of birth: March 21, 1977 Place of birth: Shiraz, Iran Nationality: Iranian Marital status: Married Professional address: PhD of Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran Tel & Fax: + 98-711-2349330 E-Mail [email protected] [email protected] Languages: English: Good Farsi: Mother Language 1 Education: Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (PhD, 2004-2011) Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran ( MS, 2000-2003) Department of Statistics, Faculty of Basic Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. ( BS, 1996-2003) Namazi School, Shiraz, Iran. (Mathematical Diploma, 1991-1995) Teaching Experiences: Biostatistics and Mathematics, Faculty of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (2008 until now) Associate Professor Biotatistics and Epidemiology, Jahrom School of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran. (2003- 2005) Biostatistics and Mathematics, Faculty of Public Health, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (2001-2008) Biostatistics, Fasa School of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran. (2004-2007) Biostatistics, Lar School of Nursing, Lar, Iran. (2004) Teaching of Statistics, Kavar Jameh University, Kavar, Iran. (2004-2005) Member: Iranian Statistical Society (ISS) 2 Certification: Ethics in Epidemiology Research & Public Health Practice Workshop. 6th IEA Eastern Mediterranean Regional Scientific Meeting, Ahwaz University of Medical Sciences, Ahwaz, Iran. (9-11 December, 2003). Ethics in Research Workshop. Jahrom School of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran. (10 March, 2004). Medical Research Methods Workshop. Jahrom School of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran. (9-13 July, 2004). Quality Management Workshop. Jahrom School of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran. -

Iranian Medicinal Plants: from Ethnomedicine to Actual Studies

medicina Review Iranian Medicinal Plants: From Ethnomedicine to Actual Studies Piergiacomo Buso 1, Stefano Manfredini 1 , Hamid Reza Ahmadi-Ashtiani 2,3, Sabrina Sciabica 1, Raissa Buzzi 1,4, Silvia Vertuani 1,* and Anna Baldisserotto 1 1 Department of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Master Course in Cosmetic Sciences, University of Ferrara, Via Luigi Borsari 43, 44121 Ferrara, Italy; [email protected] (P.B.); [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Basic Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Tehran 194193311, Iran; [email protected] 3 Cosmetic, Hygienic and Detergent Sciences and Technology Research Center, Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Tehran 194193311, Iran 4 Ambrosialab S.r.l. University of Ferrara Spinof Company, Via Mortara 171, 44121 Ferrara, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 January 2020; Accepted: 21 February 2020; Published: 26 February 2020 Abstract: Iran has a rich and diverse cultural heritage, consisting of a complex traditional medicine deeply rooted in the history of the territory that goes back to the Assyrian and Babylonian civilizations. The ethnomedical practices that can be identifiable nowadays derive from the experience of local people who have developed remedies against a wide range of diseases handing down the knowledge from generation to generation over the millennia. Traditional medicine practices represent an important source of inspiration in the process of the development of new drugs and therapeutic strategies. In this context, it is useful to determine the state of the art of ethnomedical studies, concerning the Iranian territory, and of scientific studies on plants used in traditional Iranian medicine. -

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト

Mayors for Peace Member Cities 2021/10/01 平和首長会議 加盟都市リスト ● Asia 4 Bangladesh 7 China アジア バングラデシュ 中国 1 Afghanistan 9 Khulna 6 Hangzhou アフガニスタン クルナ 杭州(ハンチォウ) 1 Herat 10 Kotwalipara 7 Wuhan ヘラート コタリパラ 武漢(ウハン) 2 Kabul 11 Meherpur 8 Cyprus カブール メヘルプール キプロス 3 Nili 12 Moulvibazar 1 Aglantzia ニリ モウロビバザール アグランツィア 2 Armenia 13 Narayanganj 2 Ammochostos (Famagusta) アルメニア ナラヤンガンジ アモコストス(ファマグスタ) 1 Yerevan 14 Narsingdi 3 Kyrenia エレバン ナールシンジ キレニア 3 Azerbaijan 15 Noapara 4 Kythrea アゼルバイジャン ノアパラ キシレア 1 Agdam 16 Patuakhali 5 Morphou アグダム(県) パトゥアカリ モルフー 2 Fuzuli 17 Rajshahi 9 Georgia フュズリ(県) ラージシャヒ ジョージア 3 Gubadli 18 Rangpur 1 Kutaisi クバドリ(県) ラングプール クタイシ 4 Jabrail Region 19 Swarupkati 2 Tbilisi ジャブライル(県) サルプカティ トビリシ 5 Kalbajar 20 Sylhet 10 India カルバジャル(県) シルヘット インド 6 Khocali 21 Tangail 1 Ahmedabad ホジャリ(県) タンガイル アーメダバード 7 Khojavend 22 Tongi 2 Bhopal ホジャヴェンド(県) トンギ ボパール 8 Lachin 5 Bhutan 3 Chandernagore ラチン(県) ブータン チャンダルナゴール 9 Shusha Region 1 Thimphu 4 Chandigarh シュシャ(県) ティンプー チャンディーガル 10 Zangilan Region 6 Cambodia 5 Chennai ザンギラン(県) カンボジア チェンナイ 4 Bangladesh 1 Ba Phnom 6 Cochin バングラデシュ バプノム コーチ(コーチン) 1 Bera 2 Phnom Penh 7 Delhi ベラ プノンペン デリー 2 Chapai Nawabganj 3 Siem Reap Province 8 Imphal チャパイ・ナワブガンジ シェムリアップ州 インパール 3 Chittagong 7 China 9 Kolkata チッタゴン 中国 コルカタ 4 Comilla 1 Beijing 10 Lucknow コミラ 北京(ペイチン) ラクノウ 5 Cox's Bazar 2 Chengdu 11 Mallappuzhassery コックスバザール 成都(チォントゥ) マラパザーサリー 6 Dhaka 3 Chongqing 12 Meerut ダッカ 重慶(チョンチン) メーラト 7 Gazipur 4 Dalian 13 Mumbai (Bombay) ガジプール 大連(タァリィェン) ムンバイ(旧ボンベイ) 8 Gopalpur 5 Fuzhou 14 Nagpur ゴパルプール 福州(フゥチォウ) ナーグプル 1/108 Pages