Addressing Correctional Officer Stress: Programs and Strategies (Issues and Practices)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Letter

SeptemberJanuary, 20092008 P.O. Box 550 • Sharpsburg, MD 21782 • 301.432.2996 • [email protected] • www.shaf.org A Letter from Our President President’s Letter The SHAF board of directors Greetings from SHAF and we wish you the best in 2009. As we close the door on 2008is pleased SHAF members to present can our be newproud of our accomplishments.As summer winds SHAF down hosted and twothe Workleaves Days, begin one to in fall, the Springit must where be time we plantedlogo, over which150 trees graces as part the of covera forscene another restoration Antietam project anniversary.along Antietam This Creek. year’s The Sharpsburg trees also fi lterHeritage pollution Festival and prevent of it fromthis newsletter.entering the creek,We deter which- willultimately expand helps to keeptwo daysthe Chesapeake and will again Bay pollution-free.feature several Our members second Work of SHAF Day, held Novembermined 1, last cleared year aboutto incorporate 250 yards providingof the Piper free Lane lectures. in the very We center hope of tothe meet battlefi you eld. there Removing and we’ll the beold happyfencing, to underbrush into and our trees logo from what this is lane perhaps will allow a walking trail from the Visitor’s Center to connect to the parking lot at the National Cemetery.the single You most may recognizable recall this is spend some time chatting about our favorite historic site. the trail that will complete the trail system from the north end of the battlefi eld to the southernCivil end.War Itbattlefield is also the projecticon, theto which youAnother donated exciting $5,000 to eventhelp construct. -

The Antietam and Fredericksburg

North :^ Carolina 8 STATE LIBRARY. ^ Case K3€X3Q£KX30GCX3O3e3GGG€30GeS North Carolina State Library Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from State Library of North Carolina http://www.archive.org/details/antietamfredericOOinpalf THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG- Norff, Carof/na Staie Library Raleigh CAMPAIGNS OF THE CIVIL WAR.—Y. THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG BY FEAISrCIS WmTHEOP PALFEEY, BREVET BRIGADIER GENERAL, U. 8. V., AND FORMERLY COLONEL TWTENTIETH MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY ; MEMBER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETF, AND OF THE MILITARY HIS- TORICAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS. NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNEE'S SONS 743 AND 745 Broadway 1893 9.73.733 'P 1 53 ^ Copyright bt CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1881 PEEFAOE. In preparing this book, I have made free use of the material furnished by my own recollection, memoranda, and correspondence. I have also consulted many vol- umes by different hands. As I think that most readers are impatient, and with reason, of quotation-marks and foot-notes, I have been sparing of both. By far the lar- gest assistance I have had, has been derived from ad- vance sheets of the Government publication of the Reports of Military Operations During the Eebellion, placed at my disposal by Colonel Robert N. Scott, the officer in charge of the War Records Office of the War Department of the United States, F, W. P. CONTENTS. PAGE List of Maps, ..«.••• « xi CHAPTER I. The Commencement of the Campaign, .... 1 CHAPTER II. South Mountain, 27 CHAPTER III. The Antietam, 43 CHAPTER IV. Fredeeicksburg, 136 APPENDIX A. Commanders in the Army of the Potomac under Major-General George B. -

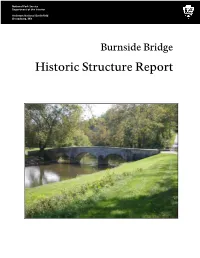

Burnside Bridge FINAL HSR.Pdf

National Park Service Department of the Interior Antietam National Battlefield Sharpsburg, MD Burnside Bridge Historic Structure Report The historic structure report presented here exists in two formats. A traditional, printed version is available for study at Antietam National Battlefield, the National Capital Regional Office of the NPS, Denver Service Center of the NPS, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, the historic structure report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps.gov for more information. Antietam National Battlefield Burnside Bridge Historic Structure Report February 2017 for Antietam National Battlefield Sharpsburg, MD by Jennifer Leeds NCPE Historical Architect Intern & Rebecca Cybularz Historical Architect Historic Preservation Training Center Office of Learning and Development Workplace, Relevancy, and Inclusion (WASO) National Park Service Frederick, MD Approved by: _________________________________________________________________ Superintendent, Antietam National Battlefield Date This page intentionally blank. Table of Contents Project Team 1 Executive Summary 3 Administrative Data 7 List of Abbreviations 10 List of Figures 11 List of Tables 12 Part 1 Developmental History Historical Background and Context 15 Chronology of Development and Use 29 Architectural Descriptions 59 Physical Description 60 Character-Defining Features 69 Condition Assessment 75 Part 2 Treatment and Use Requirements for Treatment and Use -

The Department of the Susquehanna

GLENN E. BILLET THE DEPARTMENT OF THE SUSQUEHANNA Here for the first time is the history of the military department and its com- mander who was charged with repel- ling the Confederate invaders of Penn- sylvania. INTRODUCTION Many historians state that 1863 was the crucial year of the Civil War. Pennsylvania's part in this crisis was, to say the least, of great sig- nificance, especially when the dual role of the Keystone State is consid- ered: first, Pennsylvania provided nearly one-third of Meade's total force at Gettysburg, the battle which thwarted the desire of the Confederacy to end the war quickly; secondly, the creation and organization of the De- partment of the Susquehanna helped frustrate Lee's intentions of carry- ing the war north of the Mason and Dixon line in a victorious fashion. After his triumph over Hooker at Chancellorsville, Lee decided to undertake an invasion of Pennsylvania. Whatever his specific military objectives might have been, Lee probably hoped for a quick, decisive tri- umph over the Army of the Potomac on Northern soil or the capture of an important city such as Harrisburg or Philadelphia. Such a military coup would draw away some of Grant's troops at Vicksburg for home defense and, at the same time, increase the agitation of certain disgrun- tled groups in the North against the administration. Perhaps, Lee must have thought, it might even bring the end of the war. What response did the aspirations of Lee and the South arouse in Lincoln, Stanton and Halleck? One remedy, the replacement of Joseph Hooker by George Gordon Meade at the head of the Army of the Poto- mac, was a panacea used under similar circumstances before. -

Congressional Record-Rouse

6044 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-ROUSE . NOVEMBER 29, Evan Stark Evans. NORTH CAROLINA.. G ... orge Frank Holland. Ernest L. Auman, Ashboro. Howard Pendleton Kirtley. J :-> cob Carl Kr::ifft. SOUTH CAROLINA. Otis Burge s Nesbit. J. F. Rickenbaker, Lake City. Walter Scott Rountree. A. 0. Thompson, Conway. PROMOTIONS AND APPOINTMENTS IN THE NA.VY. SOUTH DAKOTA. Commanoer Mark L. Bristol to be a captain. William }foore, Armour. Veut. Commander Roscoe C. Bulmer to be a commander. VIRGINIA. Lieut. Iloger Williams to be a lieutenant commander. Lillie L. Davis, National Soldiers Home. Lieut (Junior Grade) Guy ID. Baker to be a lieutenant. John S. Scott, Parksley. Tbe followjng-named citizens to be assistant surgeons in the WASHINGTON. Medicnl Ile;:erve Corps: Frank C. Willey, Shelton. Hubley R. Owen, and Foster H. Bowman. WISCONSIN. POSTMASTERS. Annie K. Blanclmrd, Blanchardville. ARKANSAS. Charles F. Dillett, Shawano. Irvin H. Ecker, Whitehall~ A. D. A~ee, Gui·don. Albert F. Fuchs, Loyal. J. E. Leeper, Dermott. Aloys Grimm, Cassvi11e. CALIFORXIA. David A. Holmes. MiJton. Alfred Belieu, Watts. Franz Markus, Medford. P. L. Byers, Huntington Park. John O'Neil, North Freedom. Anna l\fary Carson. Compton. Edward Porter, Cornell. 1\1. F. Cochrane. San Rafael. E. D. Singleton. Camp Douglas. E. J. Cnrne. Menlo Park. J. V. Swift, Benton. Wnlter J. De8mond. Long Bea.ch (late Longbeach). W. M. Ward, Soldiers Grove. George P. Dobyns, El Monte. Frnnk P. Firey, Pomona. Thomas F. Fogarty, Marysville. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Floyd Godfl'ey, San Dimas. Duncan A. Gray, 8oldiers Home. SATURDAY, November ~9, 1913. George Gribble, Scotia. The House met at 12 o'clock noon. -

The Antietam Manuscript of Ezra Ayres Carman

General Ezra Ayres Carman The Antietam Manuscript of Ezra Ayres Carman "Ezra Ayres Carman was Lt. Colonel of the 7th Regiment of New Jersey Volunteers during the Civil War. He volunteered at Newark, NJ on 3 Sept 1861, and was honorably discharged at Newark on 8 Jul 1862 (This discharge was to accommodate his taking command of another Regiment). Wounded in the line of duty at Williamsburg, Virginia on 5 May 1862 by a gunshot wound to his right arm in action. He also served as Colonel of the 13th Regiment of New Jersey Volunteers from 5 August 1862 to 5 June 1865. He was later promoted to the rank of Brigadier General." "Ezra Ayes Carman was Chief Clerk of the United States Department of Agriculture from 1877 to 1885. He served on the Antietam Battlefield Board from 1894 to 1898 and he is acknowledged as probably the leading authority on that battle . In 1905 he was appointed chairman of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park Commission." "The latest Civil War computer game from Firaxis is Sid Meier's "Antietam". More significant is the inclusion of the previously unpublished manuscript of Ezra Carman, the commanding officer of the 13th New Jersey Volunteers during the battle of Antietam. His 1800-page handwritten account of the battle has sat in the National Archives since it was penned and its release is of interest to people other than gamers." "As an added bonus, the game includes the previously unpublished Civil War manuscript of Ezra Carman, the commanding officer of the 13th New Jersey Volunteers. -

Oral History of James Lee Nagle

ORAL HISTORY OF JAMES LEE NAGLE Interviewed by Annemarie van Roessel Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project The Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 2000 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. CONTENTS Preface iv Outline of Topics vi Oral History 1 Selected References 155 Appendix: Curriculum Vitæ 159 Index of Names and Buildings 161 iii PREFACE A true son of the Midwest, James ‘Jim” Nagle was born into a family where building skills were paramount. Always passionate about carpentry and construction, he expanded his expertise by studying architecture on both the east and west coasts and by sating his interest in early modern Dutch and Scandinavian design philosophies though international travel and study. Nagle began his career in Chicago in a small atelier of like-minded architects, soon opening his own firm with kindred spirit Larry Booth. In the midst of Chicago’s fledgling preservation movement in the 1960s and 70s, he contributed his expertise and enthusiasm to the rescue of H.H. Richardson’s magnificent Glessner House and was a founding member of the Chicago Architecture Foundation. In the mid-1970s, he accepted an invitation to join the Chicago Seven, a brotherhood of brash young architects that challenged the reign of Miesians in Chicago through architecture and sought to reclaim the legacy of lesser-appreciated architects through writings and exhibitions. -

The Influence of Socio-Economic Background on Union Soldiers During the American Civil War John David Hoptak Lehigh University

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 2003 The influence of socio-economic background on Union soldiers during the American Civil War John David Hoptak Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Recommended Citation Hoptak, John David, "The influence of socio-economic background on Union soldiers during the American Civil War" (2003). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 782. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hoptak, John. Davia ~ The Influence of Socio-Economic Background on Union Soldiers during the American... May 2003 The Influence ofSocio-Economic Background on Union Soldiers during the American Civil War By John David Hoptak A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee ofLehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master ofArts m The Department ofHistory Lehigh University (May 2003) Table ofContents Certificate ofApproval ~ 11 Table ofContents iii List ofTables . IV Abstract 1 "The Influence ofSocio-Economic Background on Union Soldiers during the American Civil War" . 2 Bibliography . 43 Appendix 1: "Port Clinton White Males ofFighting Age and Port Clinton Civil War Enlistees Compared" 48 th Appendix 2: "Breakdown in Age ofLinked Soldiers in the 48 " 50 Appendix 3: "Foreign Born Soldiers in the 48th Pennsylvania" 51 Appendix 4: "Breakdown in Total Wealth ofLinked Soldiers in the 48th PA". 53 Appendix 5: "Prewar Occupations ofSoldiers in the 48th Pennsylvania Compared with all Union Soldiers" . 56 Appendix 6: "Breakdown in Household and Marital Status" 57 Vita 58 111 List ofTaB1~s/ Appendix 1: "Port Clinton White Males ofFighting Age in 1860 and Port Clinton Civil War Enlistees Compared" 48 Table 1: "Ages" . -

Members of the Division of Nuclear Physics, APS FROM: Benjamin F

TO: Members of the Division of Nuclear Physics, APS FROM: Benjamin F. Gibson, LANL – Secretary-Treasurer, DNP ACCOMPANYING THIS NEWSLETTER: Charles Glashausser, Rutgers, Vice Chair (2000) • APS Spring Meeting DNP Symposia Walter F. Henning, ANL, Past Chair (2000) • DNP Fall Meeting Speaker Nomination Form Benjamin F. Gibson, LANL, Secretary-Treasurer (2000) J. Dirk Walecka, College of William & Mary Divisional Councilor (December 2001) Christopher R. Gould, N. Carolina State Univ. (2000) Barry R. Holstein, U Mass (2001) Brian Serot, Indiana U (2000) T. James M. Symons, LBNL (2000) Robert E. Tribble, Texas A&M (2001) Future Deadlines Michael C. T. Wiescher, Notre Dame (2001) • 1 April 2000 — APS Fellowship Nominations • 4 May 2000 — Speaker Nominations for Fall Meeting 2. CALL FOR DNP COMMITTEE SUGGESTIONS • 1 July 2000 — Nominations for Bonner Prize • 1 July 2000 — Nominations for Bethe Prize The terms of some of the members of the following DNP committees • 1 July 2000 — Nominations for Dissertation Award expire in April 2000: Bethe, Bonner, Fellowship, Nominating, Home Page, and Education. Suggestions from the DNP membership for new members of these committees for 2000 are welcome and should be sent WWW Home Page for DNP - “http://www.phy.anl.gov/dnp/”. to Hamish Robertson. A list of committee members for 2000 will be published in the August newsletter. A worldwide web home page for the Division of Nuclear Physics is currently available at “http://www.phy.anl.gov/dnp/”. Information of interest to DNP members, such as current NP topics, deadlines for Inside . meetings, prizes, nomination forms, special announcements, and useful links are listed there. -

"The Vortex of Hell" from Richmond to Manassas in 1862

"The Vortex of Hell" From Richmond to Manassas in 1862 "The name of every officer, non-commissioned officer, and private who has shared in the toils and privations of this campaign should be mentioned... I would that I could do justice to all of these gallant officers and men in this report. As that is impossible." ~ Confederate General James Longstreet 1 2 1862 - The Peninsula Campaign While fighting raged near Richmond, on June 26th a new Union army was created from three separate commands that had been previously operating In the second year of the Civil War, Northern hopes were again raised for independently in northern Virginia. Maj. Gen. John Pope was assigned to a quick victory. However, Union Gen. George B. McClellan made little command this new force, christened the "Army of Virginia." progress beginning a spring campaign in 1862, resulting in a restless public and press. Finally forced into action, McClellan decided to move his By mid-July, Pope's new army was beginning to take shape and move massive Army of the Potomac by water to Fortress Monroe in Virginia and southward across Virginia. Even though McClellan's huge army remained from there advance up the James River Peninsula to take the Confederate at Harrison's Landing and the movement would weaken Richmond's capital of Richmond. defenses, on July 13th, Lee dispatched Jackson's wing of the army north to confront Pope and protect the vital railroad junction at Gordonsville. Gathering a force of some 63,000 men around Richmond, Confederate Lee remained with the other wing, under the command of Gen. -

O'donnellk Phd2000.Pdf

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture Author(s) O'Donnell, Katherine Publication date 2000 Original citation O'Donnell, K. 2000. Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b1306492~S0 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2000, Katherine O'Donnell http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1611 from Downloaded on 2021-10-06T06:10:51Z DP ,too 0 OO'DtJ Edmund Burke & the Heritage of Oral Culture Submitted by: Katherine O'Donnell Supervisor: Professor Colbert Kearney External Examiner: Professor Seamus Deane English Department Arts Faculty University College Cork National University of Ireland January 2000 I gcuimhne: Thomas O'Caliaghan of Castletownroche, North Cork & Sean 6 D6naill as Iniskea Theas, Maigh Eo Thuaidh Table of Contents Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" 1 Burke in Nagle Country 13 "Image of a Relation in Blood"- Parliament na mBan &Burke's Jacobite Politics 32 Burke &the School of Irish Oratory 56 Cuirteanna Eigse & Literary Clubs n "I Must Retum to my Indian Vomit" - Caoineadh's Cainte - Lament and Recrimination 90 "Homage of a Nation" - Burke and the Aisling 126 Bibliography 152 Introduction· ''To love the little Platoon" Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) ofpublic affections. -

The Final Attack Trail 1 STOP 1 - Parking Area at Driving Tour Stop 9 the Final Attack Trail Begins at Auto of the Crucial Antietam Creek Tour Stop 9

The Final Attack Trail 1 STOP 1 - Parking area at Driving Tour Stop 9 The Final Attack Trail begins at Auto of the crucial Antietam Creek Tour Stop 9. The trail is 1.7 miles in crossing behind you. Finally the length and takes 60 to 90 minutes to Confederates retreated from this walk. The terrain is rolling and the high ground defending the bridge. trail can be uneven, so good walking shoes are recommended and please For two hours thousands of stay on the trail. sweat stained, clanking, blue clad soldiers tramped by to your left and In this part of the battle, which right in preparation for the final lasted from 3:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m., advance to drive Robert E. Lee's there were five times as many Confederate army from Maryland. casualties than there were in the Approximately 8,000 Union soldiers action at the Burnside Bridge. Two would resupply and reorganize Generals were killed and Colonel into a mile wide line of battle and Harrison Fairchild's Brigade of advance across the ground that you Union soldiers suffered the highest will walk. percentage of casualties for any brigade in the Union army at the Things have quieted down on the Battle of Antietam. These final north end of the battlefield, but two and one half hours of combat the artillery in front of and behind concluded the twelve hour struggle you is still banging away as another that still ranks as the bloodiest one- battery of guns rumbles past with day battle in American history.