Oral History of James Lee Nagle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Floor, City Hall

AGENDA OF MATTERS TO BE CONSIDERED BY THE COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC l[AY ON Tuesday, December B, 2015 Room 201-A Second Floor, City Hall 1:00 p m hJ kJ ë.Èl '" fY.i i - .' (J ¡,;l , It; ,." . i-i ,,: c.J i ' 'l.i í i r ";'¡ l -1,1 |\J f"At o ORDINANGES FOR GRANTS OF PRIVILEGE IN THE PUBLIC WAY: WARD (1) 1650-1654 W. DtVtStON, LLC . 02015-8111 To construct, install, maintain and use six (6) planter railings on the public right-of-way for beautification purposes adjacent to its premises known as 1664 West Division Street. (1) GHEES|E'S PUB & GRUB - 02015-8108 To maintain and use one (1) sign over the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1365 North Milwaukee Avenue. (1) NETGHBORSPACE - 02015-81 09 To maintain and use, as now constructed, one (1) lawn hydrant on the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1255 North Hermitage Avenue. (1) wHrsKEY BUSTNESS - 02015-8110 To maintain and use one (1) sign over the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1367 North Milwaukee Avenue. (2) AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION . 02015.8117 To maintain and use, as now constructed, two (2) vaults under the public righlof-way adjacent to its premises known as 211 East Chicago Avenue. (2) CHIGAGO TITLE LAND TRUST AS SUCGESSOR TRUSTEE UNDER TRUST NO, 34369 - 02015-8120 To maintain and use one (1) sign over the public right-of-way adjacent to its premises known as 1200 North State Parkway. -

YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture

1 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture Fall 2011 Contents “Permanent Change” symposium review by Brennan Buck 2 David Chipperfield in Conversation Anne Tyng: Inhabiting Geometry 4 Grafton Architecture: Shelley McNamara exhibition review by Alicia Imperiale and Yvonne Farrell in Conversation New Users Group at Yale by David 6 Agents of Change: Geoff Shearcroft and Sadighian and Daniel Bozhkov Daisy Froud in Conversation Machu Picchu Artifacts 7 Kevin Roche: Architecture as 18 Book Reviews: Environment exhibition review by No More Play review by Andrew Lyon Nicholas Adams Architecture in Uniform review by 8 “Thinking Big” symposium review by Jennifer Leung Jacob Reidel Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern 10 “Middle Ground/Middle East: Religious review by Enrique Ramirez Sites in Urban Contexts” symposium Pride in Modesty review by Britt Eversole review by Erene Rafik Morcos 20 Spring 2011 Lectures 11 Commentaries by Karla Britton and 22 Spring 2011 Advanced Studios Michael J. Crosbie 23 Yale School of Architecture Books 12 Yale’s MED Symposium and Fab Lab 24 Faculty News 13 Fall 2011 Exhibitions: Yale Urban Ecology and Design Lab Ceci n’est pas une reverie: In Praise of the Obsolete by Olympia Kazi The Architecture of Stanley Tigerman 26 Alumni News Gwathmey Siegel: Inspiration and New York Dozen review by John Hill Transformation See Yourself Sensing by Madeline 16 In The Field: Schwartzman Jugaad Urbanism exhibition review by Tributes to Douglas Garofalo by Stanley Cynthia Barton Tigerman and Ed Mitchell 2 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 David Chipperfield David Chipperfield Architects, Neues Museum, façade, Berlin, Germany 1997–2009. -

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

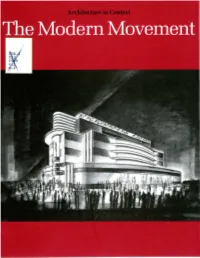

Aspects of Architectural Drawings in the Modern Era

Acknowledgments Fellows of the Program (h Architecture Society 1oiLl13l I /113'1 l~~g \JI ) C,, '"l.,. This exhibition of drawings by European and American archi Darcy Bonner Exhibition tects of the Modern Movement is the fifth in The Art Institute of Laurence Booth The Modern Movement: Selections from the Chicago's Architecture in Context series. The theme of Modern William Drake, Jr. Permanent Collection April 9 - November 20, 1988 ism became a viable exhibition topic as the Department of Archi Lonn Frye Galleries 9 and 10, The Art Institute of Chicago tecture steadily strengthened over the past five years its collection Michael Glass Lectures of drawings dating from the first four decades of this century. In Joseph Gonzales Dennis P. Doordan, Assistant Professor of Architec the case of some architects, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Bruce Gregga tural History, University of Illinois at Chicago, "The Ludwig Hilberseimer, Paul Schweikher, William Deknatel, and Marilyn and Modern Movement in Architectural Drawin gs," James Edwin Quinn, the drawings represented in this exhibition Wilbert Hasbrouck Wednesday, April 27, 1988,at 2:30 p.m. , at The Art are only a small selection culled from the large archives of their Scott Himmel Institute of Chicago. Admission by ticket only. For reservations, telephone 443-3915. drawings that have been donated to the Art Institute. In the case Helmut Jahn of European Modernists whose drawings rarely come on the mar James L. Nagle Steven Mansbach, Acting Associate Dean of the ket, such as Eric Mendelsohn, J. J. P. Oud, and Le Corbusier, the Gordon Lee Pollock Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Na Art Institute has acquired drawings on an individual basis as John Schlossman tional Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., "Reflections works by these renowned architects have become available. -

Awakening the „Forgotten Folk‟: Middle Class Consumer Activism in Post-World War I America by Mark W. Robbins B.A., Universi

AWAKENING THE „FORGOTTEN FOLK‟: MIDDLE CLASS CONSUMER ACTIVISM IN POST-WORLD WAR I AMERICA BY MARK W. ROBBINS B.A., UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN AT ANN ARBOR, 2003 A.M., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2004 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2009 ©Copyright 2009 Mark W. Robbins iii This dissertation by Mark W. Robbins is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date ___________ __________________________ Mari Jo Buhle, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ___________ __________________________ Robert Self, Reader Date ___________ __________________________ Elliott Gorn, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date ___________ __________________________ Shelia Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iv VITA Mark W. Robbins was born in Lansing, MI on August 31, 1981. He attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor where he received a B.A. in History with high honors and high distinction in 2003 with academic minors in Anthropology and Applied Statistics. In 2004, he received an A.M. in History from Brown University, where he specialized in U.S. cultural, labor and political history. His dissertation research has been funded by Brown University, the Newberry Library, the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library Association, the Historical Society of Southern California and the John R. Haynes Foundation. He has taught classes in American and African history at the University of Rhode Island, the Johns Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth and Brown University. -

President's Letter

SeptemberJanuary, 20092008 P.O. Box 550 • Sharpsburg, MD 21782 • 301.432.2996 • [email protected] • www.shaf.org A Letter from Our President President’s Letter The SHAF board of directors Greetings from SHAF and we wish you the best in 2009. As we close the door on 2008is pleased SHAF members to present can our be newproud of our accomplishments.As summer winds SHAF down hosted and twothe Workleaves Days, begin one to in fall, the Springit must where be time we plantedlogo, over which150 trees graces as part the of covera forscene another restoration Antietam project anniversary.along Antietam This Creek. year’s The Sharpsburg trees also fi lterHeritage pollution Festival and prevent of it fromthis newsletter.entering the creek,We deter which- willultimately expand helps to keeptwo daysthe Chesapeake and will again Bay pollution-free.feature several Our members second Work of SHAF Day, held Novembermined 1, last cleared year aboutto incorporate 250 yards providingof the Piper free Lane lectures. in the very We center hope of tothe meet battlefi you eld. there Removing and we’ll the beold happyfencing, to underbrush into and our trees logo from what this is lane perhaps will allow a walking trail from the Visitor’s Center to connect to the parking lot at the National Cemetery.the single You most may recognizable recall this is spend some time chatting about our favorite historic site. the trail that will complete the trail system from the north end of the battlefi eld to the southernCivil end.War Itbattlefield is also the projecticon, theto which youAnother donated exciting $5,000 to eventhelp construct. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS OCTOBER 1976 VOL. XX NO. 5 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103 • Marian C. Donnelly, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Associate Editor: Dora P. Crouch, School of Architecture RPI, Troy, New York 12181 • Assistant Editor: Richard Guy Wilson, 1318 Qxford Place, Charlottesville, Virginia22901. SAH NOTICES 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles-February 2-6. Adolf K. CONTRIBUTIONS OF BACK ISSUES OF SAH Placzek, Columbia University, is general chairman and David JOURNAL REQUESTED Gebhard, University of California, Santa Barbara, is local chairman. The Board of Directors of SAH voted at their May, 1976 Sessions will be held at the Biltmore Hotel February 3, 4 and 5. meeting to request those members who have the back (For a complete listing, please refer to the April1976 issue of the issues of the SAH Journal listed below and are willing to Newsletter.) The College Art Association of America will be part with them to donate them to the central office: Vols. meeting at the Hilton Hotel (a few blocks from the Biltmore) at I-VIII (1940-1949)- all numbers; Vol. IX (1950)-nos. 1, 2, 3; Vol. X (1951) - nos. I & 3; Vol. XI (1952)-nos. I, 2, the same time. As is customary, registration with either organiza tion entitles participants to attend either SAH or CAA sessions, 4; Vol. XII (1953) - no.-2; Vol. XIII (1954) - nos. I & 2; and a fruitful scholarly exchange is anticipated. Vol. XIV (1955)- all numbers; Vol. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1872

S1872 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 21, 2018 clear that they are opposed to the bill. Without objection, it is so ordered. truth behind why Black men were We shouldn’t be putting at risk vulner- The clerk will report the nomina- being lynched in the South. Ida B. able groups and small startups. tions en bloc. Wells’ work forced her from her home Given that, I believe that this bill, The bill clerk read the nominations in the South, and after traveling to which will clearly pass, will be some- of David J. Ryder, of New Jersey, to be New York and England, Ida settled in thing the Senate will come to deeply Director of the Mint for a term of five Chicago. regret. I will be opposing the bill. years; and Thomas E. Workman, of Among her many accomplishments, The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Sen- New York, to be a Member of the Fi- including helping launch the National ator’s time has expired. nancial Stability Oversight Council for Association of Colored Women and the The bill was ordered to a third read- a term of six years. National Association for the Advance- ing and was read the third time. Thereupon, the Senate proceeded to ment of Colored People, Ida B. Wells The PRESIDING OFFICER. The bill consider the nominations en bloc. became an early pioneer in social having been read the third time, the Mr. MCCONNELL. I ask unanimous work, fighting for justice and equality. question is, Shall the bill pass? consent that the Senate vote on the Following her death, the Chicago Hous- Mr. -

Search for Conceptual Framework in Architectural Works of Muzharullslam .'

:/ • .. Search for Conceptual Framework in Architectural Works of Muzharullslam .' 111111111 1111111111111111111111111 1191725# Mohammad Foyez Ullah This thesis is submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture August, 1997 • Department of Architecture Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology Dhaka. Bangladesh . II DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE BANGLADESH UNIVERSIlY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY Dhaka 1000 On this day, the 14'h August, Thursday, 1997, the undersigned hereby recommends to the Academic Council that the thesis titled "Search for Conceptual Framework in Architectural Works of Muzharul Islam" submitted by Mohammad Foyez Ullah, Roll no. 9202, Session 1990-91-92 is acceptable in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture. Dr. M. Shahidul Ameen Associate Professor and Supervisor Department of Architecture Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology Professor Faruque A. U. Khan Dean, Faculty of Architecture and Planning Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology ~ Professor Khaleda Rashid Member ---------- Head, Department of Architecture Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology ~<1 ';;5 Member~n*-/. Md. Salim Ullah Senior Research Architect (External) Housing and Building Research Institute Dar-us-Salam, Mirpur III To my Father IV Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincerest thank to Dr. M. Shahidul Ameen for supervising the thesis and for his intellectual impulses that he offered in making the thesis a true critical discourse. lowe my sincerest thank to Professor Meer Mobashsher Ali for his commitment to make the research on this eminent architect a reality. I am extremely grateful to Muzharul Islam. who even at his age of 74 showed his ultimate modesty by sharing his experiences and knowledge with me, which helped me to see his enterprises in a truer enlightened way. -

Muzharul Islam- Pioneer of Modern Architecture in Bangladesh

ArchSociety Page 1/9 Muzharul Islam: Pioneer of Modern Architecture in Bangladesh Kaanita Hasan, Wednesday 31 January 2007 - 18:00:00 (This essay was submitted by Architect Kaanita Hasan as a part of the course MA Architecture: Alternative Urbanism & History and Theory in the University of East London School of Architecture) His pioneering works from the 1950 s onward marked the beginning of modernism in Bangladesh (then East Pakistan). He brought about a massive change in the contemporary scene of International Style Architecture of Bangladesh. He is none other than the most influential architects of Bangladesh, Architect Muzharul Islam. Being a teacher, architect, activist and politician he has set up the structure of architectural works in the country through his varied works. His commitment to societal changes and his ethics for practicing architectures is visible in his work. These thoughts are more like a means of progress towards transformation and changes rather than drawing a conclusion by themselves. The existence of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, as a sustainable city is the most critical statement that confronts it today. It is not only difficult but would be quiet inaccurate to judge this issue from its current architectural and planning scenario. Although there is a recent ever growing building activity going on in the city, it hardly compliments the surrounding environment it is being built on. These steel, concrete and brick structures of varied types and heights are growing rapidly, resulting a decrease of open space and water bodies. Roads bear more traffic and congestions and the air we breathe in is becoming more contaminated. -

List of Illinois Recordations Under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (As of April 2021)

List of Illinois Recordations under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (as of April 2021) HABS = Historic American Buildings Survey HAER = Historic American Engineering Record HALS = Historic American Landscapes Survey HIBS = Historic Illinois Building Survey (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey) HIER = Historic Illinois Engineering Record (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Engineering Record) Adams County • Fall Creek Station vicinity, Fall Creek Bridge (HABS IL-267) • Meyer, Lock & Dam 20 Service Bridge Extension Removal (HIER) • Payson, Congregational Church, Park Drive & State Route 96 (HABS IL-265) • Payson, Congregational Church Parsonage (HABS IL-266) • Quincy, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, Freight Office, Second & Broadway Streets (HAER IL-10) • Quincy, Ernest M. Wood Office and Studio, 126 North Eighth Street (HABS IL-339) • Quincy, Governor John Wood House, 425 South Twelfth Street (HABS IL-188) • Quincy, Illinois Soldiers and Sailors’ Home (Illinois Veterans’ Home) (HIBS A-2012-1) • Quincy, Knoyer Farmhouse (HABS IL-246) • Quincy, Quincy Civic Center/Blocks 28 & 39 (HIBS A-1991-1) • Quincy, Quincy College, Francis Hall, 1800 College Avenue (HABS IL-1181) • Quincy, Quincy National Cemetery, Thirty-sixth and Maine Streets (HALS IL-5) • Quincy, St. Mary Hospital, 1415 Broadway (HIBS A-2017-1) • Quincy, Upper Mississippi River 9-Foot Channel Project, Lock & Dam No. 21 (HAER IL-30) • Quincy, Villa Kathrine, 532 Gardner Expressway (HABS IL-338) • Quincy, Washington Park (buildings), Maine, Fourth, Hampshire, & Fifth Streets (HABS IL-1122) Alexander County • Cairo, Cairo Bridge, spanning Ohio River (HAER IL-36) • Cairo, Peter T. Langan House (HABS IL-218) • Cairo, Store Building, 509 Commercial Avenue (HABS IL-25-21) • Fayville, Keating House, U.S. -

Designated Historic and Natural Resources Within the I&M Canal

Designated historic and natural resources within the I&M Canal National Heritage Corridor Federal Designations National Cemeteries • Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery National Heritage Areas • Abraham Lincoln National Heritage Area National Historic Landmarks • Adler Planetarium (Chicago, Cook County) • Auditorium Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Carson, Pirie, Scott, and Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Chicago Board of Trade Building (LaSalle Street, Chicago, Cook County) • Depriest, Oscar Stanton, House (Chicago, Cook County) • Du Sable, Jean Baptiste Point, Homesite (Chicago, Cook County) • Glessner, John H., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Hegeler-Carus Mansion (LaSalle, LaSalle County) • Hull House (Chicago, Cook County) • Illinois & Michigan Canal Locks and Towpath (Will County) • Leiter II Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marquette Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marshall Field Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Mazon Creek Fossil Beds (Grundy County) • Old Kaskaskia Village (LaSalle County) • Old Stone Gate, Chicago Union Stockyards (Chicago, Cook County) • Orchestra Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Pullman Historic District (Chicago, Cook County) • Reliance Building, (Chicago, Cook County) • Rookery Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Shedd Aquarium (Chicago, Cook County) • South Dearborn Street-Printing House Row North (Chicago, Cook County) • S. R. Crown Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Starved Rock (LaSalle County) • Wells-Barnettm Ida B., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Williams, Daniel Hale, House (Chicago, Cook County) National Register of Historic Places Cook County • Abraham Groesbeck House, 1304 W. Washington Blvd. (Chicago) • Adler Planetarium, 1300 S. Lake Shore Dr., (Chicago) • American Book Company Building, 320-334 E. Cermak Road (Chicago) • A. M. Rothschild & Company Store, 333 S. State St. (Chicago) • Armour Square, Bounded by W 33rd St., W 34th Place, S. Wells Ave. and S.