The Victorians and the Visual Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement

Andrea Korda “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Citation: Andrea Korda, “‘The Streets as Art Galleries’: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/korda-on-the-streets-as-art-galleries-hubert- herkomer-william-powell-frith-and-the-artistic-advertisement. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Korda: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement by Andrea Korda By the second half of the nineteenth century, advertising posters that plastered the streets of London were denounced as one of the evils of modern life. In the article “The Horrors of Street Advertisements,” one writer lamented that “no one can avoid it.… It defaces the streets, and in time must debase the natural sense of colour, and destroy the natural pleasure in design.” For this observer, advertising was “grandiose in its ugliness,” and the advertiser’s only concern was with “bigness, bigness, bigness,” “crudity of colour” and “offensiveness of attitude.”[1] Another commentator added to this criticism with more specific complaints, describing the deficiencies in color, drawing, composition, and the subjects of advertisements in turn. Using adjectives such as garish, hideous, reckless, execrable and horrible, he concluded that advertisers did not aim to appeal to the intellect, but only aimed to attract the public’s attention. -

Calendar of Events

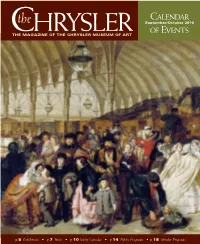

Calendar the September/October 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 5 Exhibitions • p 7 News • p 10 Daily Calendar • p 14 Public Programs • p 18 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours William Powell Frith Open during Museum hours (English, 1819–1909) Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 The Railway 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Station (detail), 1862 Norfolk, VA 23510 Oil on canvas Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Courtesy of Royal Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Holloway Collection, E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin University of London Website: www.chrysler.org Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones General admission to the Chrysler Museum Linda H. -

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

Victorian Paintings Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian paintings Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada To cite this version: Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada. Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian paintings. Polysèmes, Société des amis d’inter-textes (SAIT), 2016, L’or et l’art, 10.4000/polysemes.860. hal-02092857 HAL Id: hal-02092857 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02092857 Submitted on 8 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian Paintings This article proposes to examine the treatment of Greek myths of the golden apples in paintings by late-Victorian artists then categorized in contemporary reception as “classical” or “classic.” These terms recur in many reviews published in periodicals.1 The artists concerned were trained in the academic and neoclassical Continental tradition, and they turned to Antiquity for their forms and subjects. -

Wilde's World

Wilde’s World Anne Anderson Aesthetic London Wilde appeared on London’s cultural scene at a propitious moment; with the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in May 1877 the Aesthetes gained the public platform they had been denied. Sir Coutts Lindsay and his wife Blanche, who were behind this audacious enterprise, invited Edward Burne-Jones, George Frederick Watts, and James McNeill Whistler to participate in the first exhibition; all had suffered rejections from the Royal Academy.1 The public were suddenly confronted with the avant-garde, Pre-Raphaelitism, Symbolism, and even French Naturalism. Wilde immediately recognized his opportunity, as few would understand “Art for Art’s sake,” that paintings no longer had to be didactic or moralizing. Rather, the function of art was to appeal to the senses, to focus on color, form, and composition. Moreover, the aesthetes blurred the distinction between the fine and decorative arts, transforming wallpapers and textiles into objets d’art. The goal was to surround oneself with beauty, to create a House Beautiful. Wilde hitched his star to Aestheticism while an undergraduate at Oxford; his rooms were noted for their beauty, the panelled walls thickly hung with old engravings and contemporary prints by Burne-Jones and filled with exquisite objects: Blue and White Oriental porcelain, Tanagra statuettes brought back from Greece, and Persian rugs. He was also aware of the controversy surrounding Aestheticism; debated in the Oxford and Cambridge Undergraduate in April and May 1877, the magazine at first praised the movement as a civilizing influence. It quickly recanted, as it sought “‘implicit sanction’” for “‘Pagan worship of bodily form and beauty’” and renounced morals in the name of liberty (Ellmann 85, emphasis in original). -

Iconic Images: the Stories They Tell

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2011 Volume I: Writing with Words and Images Iconic Images: The Stories They Tell Curriculum Unit 11.01.06 by Kristin M. Wetmore Introduction An important dilemma for me as an art history teacher is how to make the evidence that survives from the past an interesting subject of discussion and learning for my classroom. For the art historian, the evidence is the artwork and the documents that support it. My solution is to have students compare different approaches to a specific historical period because they will have the chance to read primary sources about each of the three images selected, discuss them, and then determine whether and how they reveal, criticize or correctly report the events that they depict. Students should be able to identify if the artist accurately represents an historical event and, if it is not accurately represented, what message the artist is trying to convey. Artists and historians interpret historical events. I would like my students to understand that this interpretation is a construction. Primary documents provide us with just one window to view history. Artwork is another window, but the students must be able to judge on their own the factual content of the work and the artist's intent. It is imperative that students understand this. Barber says in History beyond the Text that there is danger in confusing history as an actual narrative and "construction of the historians (or artist's) craft." 1 The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines iconic as "an emblem or a symbol." 2 The three images I have chosen to study are considered iconic images from the different time periods they represent. -

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013

Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM Last updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required (*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Ford Madox Brown The Seeds and Fruits of English Poetry, 1845-1853 oil on canvas 36 x 46 cm (14 3/16 x 18 1/8 in.) framed: 50 x 62.5 x 6.5 cm (19 11/16 x 24 5/8 x 2 9/16 in.) The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Presented by Mrs. W.F.R. Weldon, 1920 William Holman Hunt The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, 1854-1860 oil on canvas 85.7 x 141 cm (33 3/4 x 55 1/2 in.) framed: 148 x 208 x 12 cm (58 1/4 x 81 7/8 x 4 3/4 in.) Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Presented by Sir John T. -

The People's Institute, the National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America

In Defense of the Moving Pictures: The People's Institute, The National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America Nancy J, Rosenbloom Located in the midst of a vibrant and ethnically diverse working-class neighborhood on New York's Lower East Side, the People's Institute had by 1909 earned a reputation as a maverick among community organizations.1 Under the leadership of Charles Sprague Smith, its founder and managing director, the Institute supported a number of political and cultural activities for the immigrant and working classes. Among the projects to which Sprague Smith committed the People's Institute was the National Board of Censorship of Motion Pictures. From its creation in June 1909 two things were unusual about the National Board of Censorship. First, its name to the contrary, the Board opposed growing pressures for legalized censorship; instead it sought the voluntary cooperation of the industry in a plan aimed at improving the quality and quantity of pictures produced. Second, the Board's close affiliation with the People's Institute from 1909 to 1915 was informed by a set of assumptions about the social usefulness of moving pictures that set it apart from many of the ideas dominating American reform. In positioning itself to defend the moving picture industry, the New York- based Board developed a national profile and entered into a close alliance with the newly formed Motion Picture Patents Company. What resulted was a partnership between businessmen and reformers that sought to offset middle-class criticism of the medium. The officers of the Motion Picture Patents Company also hoped 0026-3079/92/3302-O41$1.50/0 41 to increase middle-class patronage of the moving pictures through their support of the National Board. -

Art in the Modern World

Art in the Modern World A U G U S T I N E C O L L E G E Beata Beatrix 1863 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI The Girlhood of Mary 1849 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Ecce ancilla Domini 1850 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Our English Coasts William Holman HUNT | 1852 Our English Coasts detail 1852 William Holman HUNT The Hireling Shepherd 1851 | William Holman HUNT The Awakening Conscience 1853 William Holman HUNT The Scapegoat 1854 | William Holman HUNT The Shadow of Death 1870-73 William Holman HUNT Christ in the House of His Parents 1849 | John Everett MILLAIS Portrait of John Ruskin 1854 John Everett MILLAIS Ophelia 1852 | John Everett MILLAIS George Herbert at Bemerton 1851 | William DYCE The Man of Sorrows 1860 | William DYCE Louis XIV & Molière 1862 | Jean-Léon GÉRÔME Harvester 1875 William BOUGUEREAU Solitude 1890 Frederick Lord LEIGHTON Seaside 1878 James Jacques Joseph TISSOT The Awakening Heart 1892 William BOUGUEREAU The Beguiling of Merlin 1874 | Edward BURNE JONES Innocence 1873 William BOUGUEREAU Bacchante 1894 William BOUGUEREAU The Baleful Head 1885 Edward BURNE JONES Springtime 1873 Pierre-Auguste COT The Princesse de Broglie James Joseph Jacques TISSOT A Woman of Ambition 1883-85 James Joseph Jacques TISSOT Prayer in Cairo Jean-Léon GEROME The Boyhood of Raleigh 1870 | John Everett MILLAIS Flaming June 1895 Frederick Lord LEIGHTON Lady Lilith 1864 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Holyday 1876 | James Joseph Jacques TISSOT Autumn on the Thames 1871 James Joseph Jacques TISSOT A Dream of the Past: Sir Isumbras at the Ford 1857 | John Everett MILLAIS A Reading -

3. Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

• Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 1 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange. -

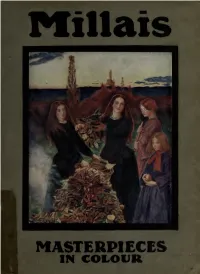

Masterpieces in Colour in M^Moma

Millais -'^ Mi m' 'fS?*? MASTERPIECES IN COLOUR IN M^MOMA FOR MA>4Y YEARS ATEACKEi;. IN THIS COLLEOE:>r55N.£>? THIS B(2);ClSONE^ANUMB€R FFPH THE LIBRARY 9^JvLK >10JMES PRESENTED TOTKEQMTARIO CDltECE 9^ART DY HIS REIATIVES D^'-CXo'.. MASTERPIECES IN COLOUR EDITED BY - - T. LEMAN HARE MILLAIS 1829--1S96 "Masterpieces in Colour" Series Artist. Author. BELLINI. Georgb Hay. BOTTICELLI. Henry B. Binns. BOUCHER. C. Haldane MacFall. burne.jones. A. Ly3 Baldry. carlo dolci. George Hay. CHARDIN. Paul G. Konody. constable. C. Lewis Hind. COROT. Sidney Allnutt. DA VINCL M. W. B ROCKWELL. DELACROIX. Paul G. Konody. DtTRER. H. E. A. Furst. FRA ANGELICO. James Mason. FRA FILIPPO LIPPI. Paul G. Konody. FRAGONARD. C Haldane MacFall. FRANZ HALS. Edgcumbe Staley. GAINSBOROUGH Max Rothschild. GREUZE. Alys Eyre MackLi.j. HOGARTH. C. Lewis Hind. HOLBEIN. S. L. Bensusan. HOLMAN HUNT. Mary E. Coleridge. INGRES. A. J. FiNBERG. LAWRENCE. S. L. Bensusan. LE BRUN, VIGEE. C. Haldane MacFail LEIGHTON. A. Lys Baldry, LUINL James Mason. MANTEGNA. Mrs. Arthur Bell. MEMLINC. W. H. J. & J. C. Wealb. MILLAIS. A. Lys Baldry. MILLET. Percy M. Turner. MURILLO. S. L. Bensusan. PERUGINO. Sblwyn Brinton. RAEBURN. James L. Caw. RAPHAEL. Paul G. Konody. REMBRANDT. JosEP Israels. REYNOLDS. S. L. Bensusan. ROMNEY. C. Lewis Hind. ROSSETTl LuciBN Pissarro. RUBENS. S. L. Bensusan. SARGENT. T. Martin Wood. TINTORETTO S. L. Bensusan. TITIAN. S. L. Bensusan. TURNER. C. Lewis Hind. VAN DYCK. Percy M. Turner. VELAZQUEZ. S. L. Bensusan. WATTEAU. C. Lewis Hinb. WATTS. W. LoFTUs Hark. WHISTLER. T. Martin Wood Others in Preparation. PLATE I.—THE ORDER OF RELEASE.