Very Pressing Television and Other Imaginary Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 © Copyright by Lindsay Nicole Giggey 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Producing Reality Stardom: Constructing, Programming, and Branding Celebrity on Reality Television by Lindsay Nicole Giggey Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair The popular preoccupation with celebrity in American culture in the past decade has been bolstered by a corresponding increase in the amount of reality programming across cable and broadcast networks that centers either on established celebrities or on celebrities in the making. This dissertation examines the questions: How is celebrity constructed, scheduled, and branded by networks, production companies, and individual participants, and how do the constructions and mechanisms of celebrity in reality programming change over time and because of time? I focus on the vocational and cultural work entailed in celebrity, the temporality of its production, and the notion of branding celebrity in reality television. Dissertation chapters will each focus on the kinds of work that characterize reality television production cultures at the network, production company, and individual level, with specific attention paid to programming focused ii on celebrity making and/or remaking. Celebrity is a cultural construct that tends to hide the complex labor processes that make it possible. This dissertation unpacks how celebrity status is the product of a great deal of seldom recognized work and calls attention to the hidden infrastructures that support the production, maintenance, and promotion of celebrity on reality television. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

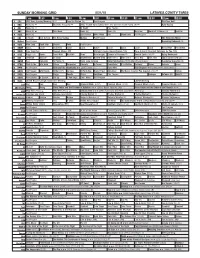

Sunday Morning Grid 5/31/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/31/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2015 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program The Simpsons Movie 13 MyNet Paid Program Becoming Redwood (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Easy Yoga Pain Deepak Chopra MD JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Pets. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Duro Pero Seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Andrea Von Foerster Music Supervisor

ANDREA VON FOERSTER MUSIC SUPERVISOR MOTION PICTURES FANTASTIC FOUR Kevin Feige, Matthew Vaughn, Simon Kinberg, 20 th Century Fox Hutch Parker, Gregory Goodman, prods. Joshua Trunk, dir. GREATER Brian Reindl, prod. Blue Ribbon Digital Media David Hunt, dir. HELICOPTER MOM Salome Breziner, Josh Cole, Stephen Israel, American Film Productions J.M.R. Luna, prods. Salome Breziner, dir. NAOMI AND ELY’S NO KISS LIST Robert Abramoff, Kristin Hanggi, Alexandra 20 th Century Fox Milchan, Emily Gerson Saines, prods. Kristin Hanggi, dir. SATURN RETURNS Anselm Clinard, Gregory Lemkin, Shawn Moonrise Pictures Tolleson, prods. Shawn Tolleson, dir. 1:30 TRAIN Howard Baldwin, Karen Elise Baldwin, G4 Productions Chris Evans, William Immerman, prods. Chris Evans, dir. GRACE OF A STRANGER (short) Troy Hollar, prod / dir. Lovemakers WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS Justin X. Duprie, Brian Udovich, prods. PLACE Zeke Hawkins, Simon Hawkins, dirs. Rough & Tumble Films A GIRL AND A GUN Liz Federowicz, Filip Jan Rymsza, Thomas Royal Road Entertainment D. Adelman, Brent Travers, prods. Filip Jan Rymsza, dir. DEVIL’S DUE John Davis, prod. 20 th Century Fox Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, Tyler Gillett, dirs. TIME LAPSE B.P. Cooper, Rick Montgomery, prods. Veritas Productions Bradley King, dir. SEA OF DARKNESS Salome Breziner, prod. Concrete Images Michael Oblowitz, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 ANDREA VON FOERSTER MUSIC SUPERVISOR BEGIN AGAIN Judd Apatow, Sam Hoffman, Ben Nearn, Exclusive Media Group Tom Rice, exec. prods. John Carney, dir. NO CLUE Brent Butt, Laura Lightbown, prods. Sparrow Media Carl Bessai, dir. GROWING UP AND OTHER LIES Nicole Diane Lederman, Katie Mustard, Embark Productions / Gold Apple Jason Weiss, prods. -

Gay and Lesbian Television Scripts and Transcripts Collection Coll2008.001

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1j49q65b No online items Inventory of the gay and lesbian television scripts and transcripts collection Coll2008.001 Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Michael C. Oliveira Processing this collection has been funded by a generous grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California, 90007 (213) 741-0094 [email protected] © 2008 Inventory of the gay and lesbian Coll2008.001 1 television scripts and transcripts collection C... Title: Gay and Lesbian Television Scripts and Transcripts collection Identifier/Call Number: Coll2008.001 Contributing Institution: ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, USC Libraries, University of Southern California Language of Material: English Physical Description: 2.8 linear feet[7 archives cartons] Date (bulk): Bulk, 1986-1997 Date (inclusive): 1965-2001 Abstract: Scripts and transcripts of broadcast and cable network television programs, specials, and made-for-television movies, most with a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender theme. The bulk of the collection contains scripts from the series Brothers (1984-1989) and Ellen (1994-1998). creator: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Access The collection is open to researchers. There are no access restrictions. Conditions Governing Use All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the ONE Archivist. Permission for publication is given on behalf of ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives at USC Libraries as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. -

Mrts 4450/5660.001: It's Not Tv, It's Hbo!

MRTS 4450/5660.001: IT’S NOT TV, IT’S HBO! University of North Texas Fall 2020 Professor: Jennifer Porst Email: [email protected] Class: T 2:30-5:20P Office Hours: By appointment Course Description: Since its debut in the early 1970s, HBO has been a powerhouse in American television and film. They regularly dominate the nominations for Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and their success has profoundly affected the television and film industries and the content they produce. Through an examination of the birth and development of HBO, we will see what a closer analysis of the channel can tell us about television, Hollywood, and American culture over the last four decades. We will also look to the future to see what HBO might become in the increasingly global and digital television landscape. Student Learning Goals: This course will provide students with an opportunity to: • Understand the industrial conditions that led to the birth and success of HBO • Gain insight into the contemporary challenges and opportunities faced by the media industries • Develop critical thinking skills through focused analysis of readings and HBO content • Communicate clearly and confidently in class discussion and presentations Required Texts: 1. Edgerton, Gary R. and Jeffrey P. Jones, Eds. The Essential HBO Reader. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008. Available as an e-book via the UNT Library website. 2. Subscription to HBO Go/Now 3. Additional required readings and screenings will be available for free through the class website. 4. Students will need to register for use of the Packback Questions site, which should cost between $10- 15 for the semester. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

2018 – Volume 6, Number

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 & 3 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor KEVIN CALCAMP Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Bump in the Night” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of Pixabay/Kellepics EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH PAUL BOOTH Minnesota State University, Moorhead DePaul University GARY BURNS ANNE M. CANAVAN Northern Illinois University Salt Lake Community College BRIAN COGAN ASHLEY M. DONNELLY Molloy College Ball State University LEIGH H. EDWARDS KATIE FREDICKS Florida State University Rutgers University ART HERBIG ANDREW F. HERRMANN Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO KATHLEEN A. KENNEDY Maryville University of St. Louis Missouri State University SARAH MCFARLAND TAYLOR KIT MEDJESKY Northwestern University University of Findlay CARLOS D. MORRISON SALVADOR MURGUIA Alabama State University Akita International -

About the Filmmakers

Regia Jon Turteltaub Con Nicolas Cage, Jay Baruchel, Monica Bellucci, Alfred Molina, Teresa Palmer. Il produttore Jerry Bruckheimer e il regista Jon Turteltaub, già creatori del franchise National Treasure, presentano L’Apprendista Stregone, una commedia avventurosa e romantica in cui un mago e il suo sventurato apprendista si ritrovano al centro dell’antico conflitto fra bene e male. Balthazar Blake (NICOLAS CAGE) è un maestro della magia che vive nell’odierna Manhattan e che intende difendere la città dalla sua nemesi per eccellenza, Maxim Horvath (ALFRED MOLINA). Ma per farlo Balthazar ha bisogno di aiuto, e recluta quindi Dave Stutler (JAY BARUCHEL), un ragazzo apparentemente normale ma che possiede doti nascoste, sottoponendolo ad un folle addestramento per fargli apprendere il più in fretta possibile tutti i segreti della magia. In questo nuovo ruolo di apprendista stregone, Dave dovrà fare appello a tutto il suo coraggio per sopravvivere all’ addestramento, arrestare le forze del male e conquistare il cuore della ragazza che ama. Uscita: 18 agosto 2010 Genere: commedia/avventura Durata:1 ora e 50 minuti Distribuito da Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures Italia Per immagini e materiali: www.image.net www.disney.it/apprendistastregone www.twitter.com/disneystregone www.facebook.com/apprendistastregoneitalia Walt Disney Pictures, il produttore Jerry Bruckheimer e il regista Jon Turteltaub, la squadra che ha lavorato alla creazione del franchise de Il mistero dei templari (National Treasure), di nuovo insieme per presentare L'Apprendista Stregone (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice) una nuova avventura emozionante che racconta la storia di uno stregone e del suo sfortunato apprendista che si trova nel bel mezzo di un antico conflitto tra il bene e il male. -

September 21, 2019

SKYLIGHT THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF WRITTEN BY WENDY KOUT DIRECTED BY TONY ABATEMARCO AND CELIA MANDELA RIVERA STARRING: EVIE ABAT, ADAM FOSTER BALLARD, ELIZA BLAIR, MICHAEL KACZKOWSKI, JOEY MILLIN, SARAH TUBERT SCENIC AND LIGHTING DESIGNER: CAROLINE ANDREW SOUND DESIGNER: CHRISTOPHER MOSCATELIO COSTUME DESIGNER: MYLETTE NORA VIDEO DESIGNER: LILY BARTENSTEIN PUBLICIST: JUDITH BORNE GRAPHIC DESIGNER: GUILLERMO PEREZ PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGERS: CHRISTOPHER HOFFMAN, GARRETT CROUCH ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS: WENDY HAMMERS, AMY PELCH PRODUCERS: GARY GROSSMAN, MICHAEL KEARNS OPENING NIGHT: SEPTEMBER 21, 2019 Adapted from Survivors by Wendy Kout commissioned, developed and produced by the Center Stage Theatre at the Louis S. Wolk Jewish Community Center of Greater Rochester, Ralph Meranto, Artistic Director. Welcome... “Collaboration, which in circumstances associated with hate-generating leadership, has often and rightfully been given a bad name. In the theatre, it is our lifeblood; the essential component that allows for creativity to thrive. In light of recent events in our world that may equate collaboration with complacency or worse, we have made an intensive effort to accentuate the positive definition of that word. Using the testimonies of Survivors of Hitler’s death camps and the gift of hope they continue to share with succeeding generations, they have become our lodestar, guiding us toward light, reframing our present dread into action. That action makes use of our skills as artists. We hope that by sharing Never Is Now with you, we may help you reframe what seems daunting into something life-affirming. For those of us collaborating on the making of this event, we’re stronger than we were when we began.