Crocodile Tears: the Life and Death of Steve Irwin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sacrificing Steve

Cultural Studies Review volume 16 number 2 September 2010 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 179–93 Luke Carman 2010 Sacrificing Steve How I Killed the Crocodile Hunter LUKE CARMAN UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY There has been a long campaign claiming that in a changed world and in a changed Australia, the values and symbols of old Australia are exclusive, oppressive and irrelevant. The campaign does not appear to have succeeded.1 Let’s begin this paper with a peculiar point of departure. Let’s abjure for the moment the approved conventions of academic discussion and begin not with the obligatory expounding of some contextualising theoretical locus, but instead with an immersion much more personal. Let’s embrace the pure, shattering honesty of humiliation. Let’s begin with a tale of shame and, for the sake of practicality, let’s make it mine. Early in September 2006, I was desperately trying to finish a paper on Australian representations of masculinity. The deadline had crept up on me, and I was caught struggling for a focusing point. I wanted a figure to drape my argument upon, one that would fit into a complicated and altogether shaky coagulation of ideas surrounding Australian icons, legends and images—someone who perfectly ISSN 1837-8692 straddled an exploration of masculine constructions within a framework of cringing insecurities and historical silences. I could think of men, I could think of iconic men, and I could think of them in limitless abundance, but none of them encapsulated everything I wanted to say. -

The Plight of Our Planet the Relationship Between Wildlife Programming and Conservation Efforts

! THE PLIGHT OF OUR PLANET fi » = ˛ ≈ ! > M Photo: https://www.kmogallery.com/wildlife/2 = 018/10/5/ry0c9a1o37uwbqlwytiddkxoms8ji1 u f f ≈ f Page 1 The Plight of Our Planet The Relationship Between Wildlife Programming And Conservation Efforts: How Visual Storytelling Can Save The World By: Kelsey O’Connell - 20203259 In Fulfillment For: Film, Television and Screen Industries Project – CULT4035 Prepared For: Disneynature, BBC Earth, Netflix Originals, National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Animal Planet, Etc. Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I cannot express enough gratitude to everyone who believed in me on this crazy and fantastic journey; everything you have done has molded me into the person I am today. To my family, who taught me to seek out my own purpose and pursue it wholeheartedly; without you, I would have never taken the chance and moved to England for my Masters. To my professors, who became my trusted resources and friends, your endless and caring teachings have supported me in more ways than I can put into words. To my friends who have never failed to make me smile, I am so lucky to have you in my life. Finally, a special thanks to David Attenborough, Steve Irwin, Terri Irwin, Jane Goodall, Peter Gros, Jim Fowler, and so many others for making me fall in love with wildlife and spark a fire in my heart for their welfare. I grew up on wildlife films and television shows like Planet Earth, Blue Planet, March of the Penguins, Crocodile Hunter, Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, Shark Week, and others – it was because of those programs that I first fell in love with nature as a kid, and I’ve taken that passion with me, my whole life. -

DER SONNENSTAAT AUSTRALIENS Jahre ALLGEMEINE INFORMATIONEN HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN in QUEENSLAND!

QUEENSLAND 2018/19 25 DER SONNENSTAAT AUSTRALIENS Jahre ALLGEMEINE INFORMATIONEN HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN IN QUEENSLAND! Sie träumen schon lange von einer faszinierenden Reise nach Australien? Wer ist die Best of Travel Group? Der Bundesstaat Queensland ist voller Überraschungen und unvergesslicher Erlebnisse. Die Sonne taucht Die Gruppe wurde 1993 gegründet und ist eine Ein- die Land schaften in das schönste Licht: tiefrotes Outback, üppig grüner Regenwald, goldene Strände, blau kaufsgemeinschaft unabhängiger Reise veranstalter schimmernde Ozeane und bunte Korallenriffe. Lassen Sie sich verzaubern von der einmaligen Flora und in Deutschland, den Niederlanden, Belgien und der Fauna, faszinieren von lebhaften Metro polen und vom weiten Outback. Schweiz. 11 starke Partner mit langjähriger Erfahrung und sehr guten Ziel gebietskenntnissen über Australien Erleben Sie die spektakulären Plätze & Routen auf eigene Faust stehen für Sie bereit. • Gateways Brisbane & Cairns: Metropolen sowie Ausgangspunkte mit internationalen Flughäfen Darüber hinaus bieten wir Ihnen noch die folgenden • Australia‘s Nature Coast: Strände, Regenwald und Riffe im Süden Queenslands Spezial-Kataloge an: • Great Barrier Reef Islands: schönste Inseln des Great Barrier Reef von Nord nach Süd Australien, Indischer Ozean, Afrika, Tauchen, • Great Tropical Drive: tropischer Norden mit atemberaubenden Sonnenuntergängen, tropischem Regen- Neuseeland /Südsee, Südamerika & Asien. wald und weitem Hinterland • Outback: ein Abenteuer mit faszinierenden Nationalparks, weiten Landschaften und unvergesslichen Menschen Viel Spaß beim Lesen und Planen! Die Australien-Liebhaber der Best of Travel Group (BoTG) haben für Sie ein vielfältiges Angebot zusammen- gestellt. Alle Angebote in diesem Katalog sind mit den Reisen im Hauptkatalog Australien kombinierbar; mit der Fluglinie Ihrer Wahl und auf Wunsch mit weiteren Reise leistungen, die Sie vielleicht in anderen Katalogen gefunden haben. -

Steve Irwin on Drugs! - Never

Steve Irwin on drugs! - Never Late Summer in 2004 I was in my Sydney office and took a phone call from the HR department manager at Australia Zoo in Qld. I had launched Drug-Safe Australia about four and a half years previously, worked hard to build a viable business with a great reputation. As a result, I was used to getting calls through word of mouth recommendations but this one certainly interested me as I had been a great admirer of Steve and Terri Irwin for a couple of years. It seems that Steve was concerned about drug use amongst his young and enthusiastic team of helpers. One incident in particular had recently made him aware how easy it was to have a tragic accident, even though he himself had grown up with the knowledge and respect crocodiles deserved there were others he couldn’t be so sure of. Steve and Terri’s house backed onto Australia Zoo. It was in fact their front yard. Steve’s notoriety had exploded across the world and he and his family were having difficulty in finding quiet moments to themselves. One of Steve’s greatest pleasures was to walk with his 5-year-old daughter Bindi through the crocodile areas after the Park had closed. One afternoon shortly before I was called, Steve was enjoying his afternoon walk only to find many of the gates on the enclosures were wide open and some smaller crocs were not where they should have been. It turned out that one of his staff, (a young female) had been using marijuana for some time with resulting hallucinations. -

LISTENING (Time: 32 Minutes) Task 1. 1. You Hear a Boy Making a Phone Call. Why Is He Phoning? a to Ask for Money B to Explai

ВСЕРОССИЙСКАЯ ОЛИМПИАДА ШКОЛЬНИКОВ ПО АНГЛИЙСКОМУ ЯЗЫКУ 2013/2014 Второй (окружной) этап 9-11 класс LISTENING (Time: 32 minutes) Task 1. You will hear people talking in eight different situations. For questions 1-8, choose the best answer (A, B or C). 1. You hear a boy making a phone call. Why is he phoning? A to ask for money B to explain why he is late C to tell someone where he is 2. You hear two friends talking at school. How does the girl feel now? A tired B happy C nervous 3. You hear part of a music programme on the radio. Where is the speaker? A in a club B on a boat C at the beach 4. You hear two friends talking about some shoes they see in a shop window. What do they agree about? A The shoes are too expensive. B The heels are too high. C The colour is too dark. 5. You hear a girl talking to her brother. Why is she annoyed with him? A He didn’t buy any milk. B He lost his keys. C He didn’t send her a message. 6. You hear two friends talking about day out. Where are they going? A to take part in a sports event B to watch a sports event C to visit a sports museum 7. You hear a teacher talking to her class. What does she want them to do? A take some notes B write an essay C prepare a presentation 8. You hear a brother and sister talking in their kitchen at home. -

POLLUTION STUDIES of the GANGA RIVER. Biomonitoring Of

CROCODILE SPECIALIST GROUP _____________________________________________________________________________________ NEWSLETTER VOLUME 23 No. 1 ● JANUARY 2004 – MARCH 2004 IUCN - World Conservation Union ● Species Survival Commission The CSG NEWSLETTER is produced and distributed by the Crocodile Specialist Group of CROCODILE the Species Survival Commission, IUCN – The World Conservation Union. CSG NEWSLETTER provides information on the conservation, status, news and current events concerning crocodilians, SPECIALIST and on the activities of the CSG. The NEWSLETTER is distributed to CSG members and, upon request, to other interested individuals and organizations. All subscribers are asked to GROUP contribute news and other materials. A voluntary contribution (suggested $40.00 US per ____________________________ year) is requested from subscribers to defray expenses of producing the NEWSLETTER. All communications should be addressed to: Dr. J.P. Ross, Executive Officer CSG, Florida NEWSLETTER Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA. Fax 1 352 392 9367, ____________________________ E-mail <[email protected]>. VOLUME 23 Number 1 JANUARY 2004 – MARCH 2004 PATRONS We gratefully express our thanks to the IUCN−The World Conservation Union following patrons who have donated to the CSG Species Survival Commission conservation program during the last year. ____________________________ Big Bull Crocs! ($25,000 or more annually or in aggregate donations) Prof. Harry Messel, Chairman Japan, JLIA − Japan Leather & Leather Goods IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group Industries Association, CITES Promotion School of Physics Committee & All Japan Reptile Skin and University of Sydney Leather Association, Tokyo, Japan. Australia Mainland Holdings Ltd., Lae, Papua New Guinea. Heng Long Leather Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore. EDITORIAL OFFICE: Reptilartenshutz, Offenbach am Main, Germany. Florida Museum of Natural History D. -

An Evening with Chris Palmer the BEST and WORST of WILDLIFE

An Evening with Chris Palmer THE BEST AND WORST OF WILDLIFE FILMS Environmental Film Festival in the Nation’s Capital By Professor Chris Palmer Distinguished Film Producer in Residence Director, Center for Environmental Filmmaking School of Communication, American University [email protected]; (202) 885-3408 www.environmentalfilm.org Tuesday, March 20, 2012 A few days ago I received the following e-mail from the author and journalist Mark Dowie. He wrote: On a recent trip to Ecuador I befriended a renowned wildlife photographer. Over drinks one evening he invited me to join him on a shoot the next day. His prey was a very rare and beautiful tropical snake. We met the next morning and drove with a small crew to the edge of the rainforest. I was braced for a long exploratory trek into the wild in search of the elusive viper. Fortunately we didn't have to go far. His porter had one in a cloth bag. He removed it from the bag and placed it on the branch of a tree three paces into the rainforest. The snake coiled itself comfortably around the branch and posed while lights were assembled, lit, and some perfect shots were captured. On the way back to Quito my friend confessed that most of his shots were somehow posed like this. Mark Dowie added, “I'm sure this is not new or shocking to you. But it did rather spoil all those hours I'd spent watching Wild Kingdom, Nature, Attenborough and others on Sunday morning TV as a child.” As many of you know, I published a book in 2010 called Shooting in the Wild which discussed many examples of unethical wildlife filmmaking like the one Mark Dowie described. -

Crikey! It's the Irwins

Paul Schur, 212-548-5588 For Immediate Release: [email protected] September 12, 2018 Nicole VanderPloeg, 212-548-5176 [email protected] Katherine Wilkins, 212-548-4923 [email protected] THE IRWIN FAMILY – TERRI, BINDI AND ROBERT – COME HOME TO ANIMAL PLANET IN “CRIKEY! IT’S THE IRWINS” WHICH LAUNCHES AS A GLOBAL SERIES PREMIERE OCT. 28 AT 8PM ET/PT -The Irwins return to Animal Planet for the first time as a family in all-new series that continues Steve Irwin’s legacy - Lace up your boots because you’re about to embark on the journey of a lifetime with the family that’s bringing khaki back! The Irwins – Terri, Bindi and Robert – return to Animal Planet in a new series that gives audiences an all-access, front row seat to experience the sights and sounds of their thrilling wildlife adventures around the globe and the amazing animals that continue to inspire their conservation efforts. From running Australia’s largest family-owned zoo, Australia Zoo in Queensland, to crisscrossing the world protecting and celebrating the most wondrous animals on the planet, The Irwins work thoughtfully and tirelessly to carry on Steve’s mission to bring people closer to animals and ignite the connection that will ensure an abundance of wildlife for generations to come. CRIKEY! IT’S THE IRWINS launches as a global series premiere beginning Sunday, October 28 at 8pm ET/PT and will be seen in Animal Planet’s 360 million homes around the world. CRIKEY! IT’S THE IRWINS features the Irwins working together to care for more than 1,200 animals at Australia Zoo; overseeing a world class wildlife hospital, the largest of its kind in the world; and conducting high-octane global expeditions. -

Chef for Our Kids.” White Remarked

Local coverage since 1951 Oden Woods and Waters Spring MONTGOMERY projects underway COUNTY NEWS Page 5 USPS 361 - 700 • 75¢ • Vol. 68 • Issue 11 • Thursday, March 14, 2019 • 1 Section • 10 Pages • Published in Mount Ida, Arkansas News Briefs Mount Ida Lions say no to eight man football DEWAYNE HOLLOWAY Ouachita National [email protected] Forests recreation MOUNT IDA - After months of speculation, Mount Ida Head Coach Zack Wuichet has put areas opening for to rest the rumors of the Lions moving to eight season man football in the 2019 football season. Talk of a move to eight man football began The Ouachita and Ozark-St. Francis National Forests are even before the start of the 2018 season. beginning seasonal openings of A decline in school enrollment coupled with recreation areas and facilities in a decline in interest in football among high March. school students were among the reason for the Visitors to the 1.8 million-acre discussion. Ouachita National Forest and 1.2 Mike White, former coach and now super- million-acre Ozark-St. Francis intendent at Mount Ida High School, stated National Forests will find diverse that he had contacted the Arkansas Activities recreational activities available to Association last year about the possibility, but them. only as a last resort. Recreation contributes greatly “Regular 11 man football is always what we to the physical, mental, and spiri- want to play at Mount Ida, but we also always tual health of individuals, bonds want to provide the opportunity to play football family and friends, instills pride in DEWAYNE HOLLOWAY | Montgomery County News heritage, and provides economic Raul Ortiz measures out some spices as family, friends and K-12 Culinary Connection’s Chef for our kids.” White remarked. -

Executive Hopefuls Start Lining up WILDLIFEWARRIORS

STREAK FINAL PLAY FAILS DUCKS unablE TO FIRE ENDS OFF A LAST-SECOND SHOT MEN BEAT SPORTS » PAGE 5 USC IN L.A. SPORTS » PAGE 6 OREGON .COM DA I LYT EMhe independent student newspaperE at the UniversityRAL of Oregon | Since 1900 | Volume 111,D Issue 101 FRIDAY | FEBRUARY 26, 2010 CAMPUS WORLD women’s WILDLIFE WRAP-UP WARRIORS SEE UO-USC GAME The Irwin family addressed a group of children to encourage involvement with conservation and preservation HIGHLIGHts AND POst- GAME INTERVIEWS WITH taYLOR LILLEY AND COACH WESTHEAD DAILYEMERALD.COM/MULTIMEDIA CAMPUS Governor candidate visits with students Bill Bradbury spoke with ASUO, ASLCC presidents about educational funding IAN GERONIMO | NEWS REPORTER esterday afternoon, the EMU was flooded with children patiently waiting to be let into the ballroom to see Bindi Democratic gubernatorial candidate and Robert Irwin speak about their experiences as the chil- Bill Bradbury visited the University last dren of the late “Crocodile Hunter,” Steve Irwin. night to speak about issues important to YIn September 2006, Steve Irvin died after being stung by a stingray college students — namely, the cost of while snorkeling, but Irwin’s wife Terri, a Eugene native, and their higher education. children are continuing his work by promoting causes to preserve Bradbury called the education forum and protect the Earth’s wildlife. “Students Speak Up,” and he maintained Yesterday’s event, “Empowering the Next Generation of Wildlife an open dialogue with approximately a Warriors,” aimed to educate children about current issues regard- dozen students in the EMU Boardroom ing wildlife conservation and preservation. Terri, Bindi and Robert and others who asked questions via PHOTOS BY SHAWN HATJES | PHOTOGRAPHER TuRN TO IRWIN | PaGE 4 Facebook. -

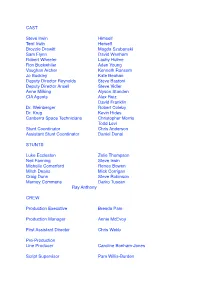

The Crocodile Hunter Collision Course Tail Credits

CAST Steve Irwin Himself Terri Irwin Herself Brozzie Drewitt Magda Szubanski Sam Flynn David Wenham Robert Wheeler Lachy Hulme Ron Buckwhiler Aden Young Vaughan Archer Kenneth Ransom Jo Buckley Kate Beahan Deputy Director Reynolds Steve Bastoni Deputy Director Ansell Steve Vidler Anne Milking Alyson Standen CIA Agents Alex Ruiz David Franklin Dr. Weinberger Robert Coleby Dr. Krug Kevin Hides Canberra Space Technicians Christopher Morris Todd Levi Stunt Coordinator Chris Anderson Assistant Stunt Coordinator Daniel Donai STUNTS Luke Eccleston Zelie Thompson Neil Fanning Steve Irwin Michelle Comerford Renee Bowen Mitch Deans Mick Corrigan Craig Dunn Steve Robinson Marney Commens Darko Tuscan Ray Anthony CREW Production Executive Brenda Pam Production Manager Annie McEvoy First Assistant Director Chris Webb Pre-Production Line Producer Caroline Bonham-Jones Script Supervisor Pam Willis-Burden Second Assistant Director Angella McPherson Third Assistant Director Jo Suna Production Accountants Trish Ashenden Ben Breen Petrece Horne Post Production Accountant Kirsten Le Bon Assistant to John Stainton/ The Irwins Justin Lyons Assistant to Arnold Rifkin Martha Haight Production Coordinators Jennine Heymer Sheila Lind Production Secretary Susannah Ingham-Myers Camera Operator Anthony Politis 1st Assistant Camera David Elmes Clapper Loader Cameron Murchison BTS Camera Trevor Smith Chief Lighting Technician Graham Rutherford Assistant Lighting Technician Steve Gordon Key Grip Lester Bishop Grip Sean Aston Production Sound Recordist Paul "Salty" Brincat -

Ripple Marks B Y C H E Ry L Ly N D Y B a S

This article has This been published in or collective redistirbution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The approval portionthe ofwith any permitted articleonly photocopy by is of machine, reposting, this means or collective or other redistirbution Ripple Marks B Y C H E RY L LY N D Y B A S The Story Behind the Story Oceanography , Volume 20, Number 4, a quarterly journal of The 20, Number 4, a quarterly , Volume Winter Ice on Lakes, Rivers, Ponds GO ing , G O ing , G O N E? If you’re planning to ice skate on a local lake or river this winter, you may need to think twice, according to scientists John Magnuson, Olaf Jensen, and Barbara Benson of the University of Wisconsin at Madison and their colleagues. O ceanography Society. Copyright 2007 by The 2007 by Copyright Society. ceanography From sources as diverse as newspaper archives, transportation ledgers, and reli- gious observances, the researchers have amassed 150 years of lake and river ice records spanning the Northern Hemisphere. during a period of rapid climate warming Almost all show a steady trend of fewer (1975–2004). They published their results days of ice cover. in the September 2007 issue of the journal Photos courtesy of John Magnuson, If the pattern continues, only in Currier Limnology & Oceanography. University of Wisconsin at Madison O Average rates of change in ice freeze and Society. ceanography and Ives prints will ice skaters twirl across O ceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or Th e [email protected] Send Society.