Recovery of Pulmonary Function After Lung Wedge Resection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anesthesia for Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery

23 Anesthesia for Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Edmond Cohen Historical Considerations of Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy ....................................... 331 Medical Thoracoscopy ................................................................................................. 332 Surgical Thoracoscopy ................................................................................................. 332 Anesthetic Management ............................................................................................... 334 Postoperative Pain Management .................................................................................. 338 Clinical Case Discussion .............................................................................................. 339 Key Points Jacobaeus Thoracoscopy, the introduction of an illuminated tube through a small incision made between the ribs, was • Limited options to treat hypoxemia during one-lung venti- first used in 1910 for the treatment of tuberculosis. In 1882 lation (OLV) compared to open thoracotomy. Continuous the tubercle bacillus was discovered by Koch, and Forlanini positive airway pressure (CPAP) interferes with surgi- observed that tuberculous cavities collapsed and healed after cal exposure during video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery patients developed a spontaneous pneumothorax. The tech- (VATS). nique of injecting approximately 200 cc of air under pressure • Priority on rapid and complete lung collapse. to create an artificial pneumothorax became a widely used • Possibility -

Anesthesia for Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery

Thoracic Anesthesia Can Be a Pleasure! Tips and Tricks For Maximizing Success Karen Sibert, MD Associate Clinical Professor Department of Anesthesiology & Perioperative Medicine David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA UCLA Health Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment in many areas of oncology, lung cancer remains a deadly disease and is the major source of the increasing caseload of thoracic surgery procedures today. A steadily increasing proportion of these cases are diagnosed in women. Complete surgical excision of tumor remains the only hope of cure. With more cardiac procedures moving from the OR to the cardiac catheterization laboratory, many cardiac surgeons are returning for fellowships in the burgeoning field of minimally invasive thoracic surgery. Only about 14% of lung carcinomas are of the small cell type; the remainder are squamous or adenocarcinomas which are operable if diagnosed early. Anesthesia for minimally invasive, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is similar to anesthesia for open thoracic cases in many respects. However, achieving lung isolation quickly and completely is even more important, since even a slightly inflated lung may obstruct the surgeon’s view. Procedures that are amenable to VATS include: Mediastinoscopy Wedge resection or lung biopsy Lobectomy or segmentectomy Pleurodesis, mechanical or talc, for pleural effusion or spontaneous pneumothorax Decortication, including evacuation of empyema or hemothorax Lung volume reduction as treatment for severe emphysema. Any patient may be a candidate regardless of extremes of age or pulmonary disease. Procedures still requiring open thoracotomy include pneumonectomy, tracheal resection, and chest wall resection. The advantages of VATS include decreased hospital length of stay, decreased morbidity, and the ability to do more cases per day in each OR. -

Post-Pneumonectomy Changes Charles-Lwanga Bennin, MD

Case Reports Post-Pneumonectomy Changes Charles-Lwanga Bennin, MD Case shift in keeping with prior right pneumonectomy. There were several surgical clips seen in the right hemithorax. The left A 71-year-old woman, with a history of non-small cell lung lung field was unremarkable without pneumothorax, pleural cancer (NSCLC) with subsequent pneumonectomy presented effusion, pulmonary edema or focal consolidation. The cardio- with worsening dyspnea on exertion and non-productive cough. mediastinal silhouette evaluation was severely limited due to The patient first noted the shortness of breath and cough 4 significant left-to-right mediastinal shift. The chest radiograph weeks prior to presentation, which were refractory to albuterol was interpreted by radiology as “stable post-pneumonectomy nebulization. The patient also reported a 6 lb. weight loss during changes with no effusions, edema or consolidation.” A this time period. She denied fevers, chills, night sweats or chest computed tomography scan was revealed hilar adenopathy with pain. The patient was diagnosed with NSCLC 11 years ago and mass effect as well as a new 3 mm nodule in the left lower lobe. underwent a right-sided extrapleural pneumonectomy at that A diagnosis of small cell cancer was made from bronchoscopy time. She received no radiation or chemotherapy. She did not and subsequent tissue biopsy. A nuclear bone scan revealed require home oxygen and reported a generally good functional no metastatic disease and the patient was treated with 3 doses status prior to the development of her latest symptoms. Other of cisplatin and etoposide. She was discharged home in stable past medical history included hyperlipidemia. -

4. Mediastinal Staging at the Time of Lung Resection

CHAPTER 5 | Invasive Mediastinal Staging Overview 93 overall. However, this latter value heavily depends on the indications for mediastinos- copy. 7 For example, in patients with clinical stage I disease, the incidence of nodal in- volvement detected by mediastinoscopy is only 3% and that detected by thoracotomy is only 5.6%. 2 Newer staging modalities such as EBUS and EUS are dependent on ultrasound local- ization of lymph nodes. In EBUS-guided transbronchial needle aspiration, nodal biop- sies are usually not attempted if the nodes cannot be visualized using ultrasonography, so these stations are often considered clinically negative. Nodes not visualized on ultrasonography are highly likely to be benign, and EBUS has a very low false nega- tive rate for detecting nonbiopsied “normal” nodes. 8 In contrast, EUS has a false negative rate of 13% when the nodes are radiographically normal; however, this rate is higher—about 23%—in patients with other mediastinal nodal involvement. This indicates that mediastinoscopy or VATS should be used to complete mediastinal stag- ing believed to be incomplete using EBUS alone or EBUS combined with EUS. (Please see Chapter 6 on the controversies of EBUS/EUS.) Comparative studies have dem- onstrated that mediastinoscopy offers a greater number of nodes sampled, a greater number of stations sampled, and more conclusive fi ndings than EBUS or EUS.9–11 Documentation of ipsilateral N2 disease alone is often insuffi cient to inform treatment recommendations; the status of the contralateral nodes must also be documented to enable surgeons to make specifi c recommendations regarding possible resection after induction therapy. -

Pulmonary Complications Following Lung Resection* a Comprehensive Analysis of Incidence and Possible Risk Factors

Pulmonary Complications Following Lung Resection* A Comprehensive Analysis of Incidence and Possible Risk Factors Franc¸ois Ste´phan, MD, PhD; Sophie Boucheseiche, MD; Judith Hollande, MD; Antoine Flahault, MD, PhD; Ali Cheffi, MD; Bernard Bazelly, MD; and Francis Bonnet, MD Study objectives: To assess the incidence and clinical implications of postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) after lung resection, and to identify possible associated risk factors. Design: Retrospective study. Setting: An 885-bed teaching hospital. Patients and methods: We reviewed all patients undergoing lung resection during a 3-year period. The following information was recorded: preoperative assessment (including pulmonary function tests), clinical parameters, and intraoperative and postoperative events. Pulmonary complications were noted according to a precise definition. The risk of PPCs associated with selected factors was evaluated using multiple logistic regression analysis to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Results: Two hundred sixty-six patients were studied (87 after pneumonectomy, 142 after lobectomy, and 37 after wedge resection). Sixty-eight patients (25%) experienced PPCs, and 20 patients (7.5%) died during the 30 days following the surgical procedure. An American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) score > 3 (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.16; p < 0.02), an operating time > 80 min (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.09 to 3.97; p < 0.02), and the need for postoperative mechanical ventilation > 48 min (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.75; p < 0.04) were independent factors associated with the development of PPCs, which was, in turn, associated with an increased mortality rate and the length of ICU or surgical ward stay. -

Lung Wedge Resection, Pulmonary Metastasis (Metastasectomy)

Surgical Services: Thoracoscopy; Lung Wedge Resection, Pulmonary Metastasis (Metastasectomy) POLICY INITIATED: 06/30/2019 MOST RECENT REVIEW: 06/30/2019 POLICY # HH-5566 Overview Statement The purpose of these clinical guidelines is to assist healthcare professionals in selecting the medical service that may be appropriate and supported by evidence to improve patient outcomes. These clinical guidelines neither preempt clinical judgment of trained professionals nor advise anyone on how to practice medicine. The healthcare professionals are responsible for all clinical decisions based on their assessment. These clinical guidelines do not provide authorization, certification, explanation of benefits, or guarantee of payment, nor do they substitute for, or constitute, medical advice. Federal and State law, as well as member benefit contract language, including definitions and specific contract provisions/exclusions, take precedence over clinical guidelines and must be considered first when determining eligibility for coverage. All final determinations on coverage and payment are the responsibility of the health plan. Nothing contained within this document can be interpreted to mean otherwise. Medical information is constantly evolving, and HealthHelp reserves the right to review and update these clinical guidelines periodically. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without permission from HealthHelp. All -

Preoperative Pulmonary Evaluation for Lung Resection

PCCP 17th MIDYEAR CONVENTION State-of-the Art Pulmonology: Convergence of Practice August 7, 2014 Preoperative Pulmonary Evaluation for Lung Resection Outline of Discussion Objectives of preoperative pulmonary evaluation of patients for surgical resection Use of predicted postoperative pulmonary function parameters to identify patients at increased risk for complications after lung resection Prediction of postoperative pulmonary function by technique of simple calculation and use of lung perfusion scan Algorithm for preoperative evaluation of patients for lung resection Reduction of Pulmonary Function after Resection Across various studies, postoperative pulmonary function values were assessed at various time intervals after lobectomy or pneumonectomy: • FEV1: 84% - 91% of preoperative values for lobectomy, 64% - 66% for pneumonectomy • DLCO : 89% - 96% of preoperative values after lobectomy 72% - 80% after pneumonectomy. • VO2 max: 87% - 100% of preoperative values after lobectomy 71% - 89% after pneumonectomy. P. Mazzone. Preoperative evaluation of the lung resection candidate. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine May 2012; Vol 79, e-S17-22 Why do we do preoperative pulmonary evaluation? • Physiologic changes in the respiratory system occur in all patients undergoing surgical/anesthetic procedures. • These changes may lead to complications, mortality and/or morbidity. Postoperative Complications (Within 30 days of surgery) • Acute CO2 retention (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) • Prolonged mechanical ventilation (> 48 h) • Infections (bronchitis & pneumonia) • Atelectasis (necessitating bronchoscopy) • Bronchospasm • Exacerbation of the underlying chronic lung disease • Pulmonary embolism • Symptomatic cardiac arrhythmias • Myocardial infarction • Death C. Wyser et al. Prospective Evaluation of an Algorithm for the Functional Assessment of Lung Resection Candidates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:1450–1456. F. Grubisic-Cabo et al., Preoperative Pulmonary Evaluation for Pulmonary and Extrapulmonary Operations. -

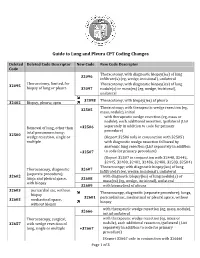

Guide to Lung and Pleura CPT Coding Changes

Guide to Lung and Pleura CPT Coding Changes Deleted Deleted Code Descriptor New Code New Code Descriptor Code Thoracotomy, with diagnostic biopsy(ies) of lung 32096 infiltrate(s) (eg, wedge, incisional), unilateral Thoracotomy, limited, for Thoracotomy, with diagnostic biopsy(ies) of lung 32095 biopsy of lung or pleura 32097 nodule(s) or mass(es) (eg, wedge, incisional), unilateral 32098 Thoracotomy, with biopsy(ies) of pleura 32402 Biopsy, pleura; open Thoracotomy; with therapeutic wedge resection (eg, 32505 mass, nodule), initial with therapeutic wedge resection (eg, mass or nodule), each additional resection, ipsilateral (List Removal of lung, other than +32506 separately in addition to code for primary total pneumonectomy; procedure) 32500 wedge resection, single or (Report 32506 only in conjunction with 32505) multiple with diagnostic wedge resection followed by anatomic lung resection (List separately in addition +32507 to code for primary procedure) (Report 32507 in conjunction with 32440, 32442, 32445, 32480, 32482, 32486, 32488, 32503, 32504) Thoracoscopy; with diagnostic biopsy(ies) of lung Thoracoscopy, diagnostic 32607 infiltrate(s) (eg, wedge, incisional), unilateral (separate procedure); 32602 with diagnostic biopsy(ies) of lung nodule(s) or lungs and pleural space, 32608 mass(es) (eg, wedge, incisional), unilateral with biopsy 32609 with biopsy(ies) of pleura 32603 pericardial sac, without Thoracoscopy, diagnostic (separate procedure); lungs, biopsy 32601 pericardial sac, mediastinal or pleural space, without mediastinal -

(VATS) and Thoracotomy

ADDRESSOGRAPH DATA INFORMED CONSENT INFORMATION THORACOTOMY The purpose of this document is to provide written information regarding the risks, benefits and alternatives of the procedure named above. This material serves as a supplement to the discussion you have with your physician. It is important that you fully understand this information, so please read this document thoroughly. If you have any questions regarding the procedure, ask your physician prior to signing the consent form. We appreciate your selecting UCLA Healthcare to meet your needs. The Procedure: Thoracotomy is usually performed to remove a cancer of the lung. In some cases, it may be performed to treat tuberculosis or fungal infection. Surgery is the most effective and potentially curative procedure for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. The surgery must obtain complete removal of all the tumor on the same side of the chest to be effective. Incomplete removal of the tumor gives no survival advantage. Various procedures on the lung include: Lobectomy: Involves the entire removal of one lobe of the lung along with all draining lymph nodes in the region of the primary tumor. Pneumonectomy: An entire lung is removed and major pulmonary function is sacrificed. Segmentectomy: Removes the tumor and less surrounding lung than a lobectomy. Usually reserved for older patients with major pulmonary function defects. Wedge resection: Removes only a small wedge of lung containing the tumor. Video Assisted Thoracoscopic (VATS) procedure (video): Performed through small openings in the chest, using a fiber optic scope connected to a monitor to guide the instruments. Benefits You might receive the following benefits. -

31Ada520558ff133638d3a0654c

Korean J Anesthesiol 2013 August 65(2): 174-176 Letter to the Editor http://dx.doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2013.65.2.174 Anesthesia under cardiopulmonary bypass for video assisted thoracoscopic wedge resection in patient with spontaneous pneumothorax and contralateral post-tuberculosis destroyed lung Joo-Duck Kim1, Eun Sung Ko2, Jee-Young Kim2, and Seong-Hyop Kim2 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, 1Kosin University Gospel Hospital, Busan, 2Konkuk University Medical Center, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Pneumothorax with contralateral destroyed lung is a rare preoperative evaluation showed pneumothorax with chest condition. However, the anesthetic management poses signi- tube in the left lung and the right lung was destroyed with fi cant risks and can be quite challenging because conventional marked volume loss with deviation of trachea to right. one-lung ventilation (OLV) for wedge resection in pneumo- Computed tomography showed multiple bullae, fibrotic bands thorax with contralateral destroyed lung is impossible. and pneumothorax with chest tube in the left lung. Further, a A 69-year-old man with height 167 cm and weight 57 kg destroyed lung with bronchopleural fistula (BPF) at the right was scheduled for video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lung was visible (Fig. 1). due to pneumothorax in left lung. A thoracostomy tube was Due to contralateral post-tuberculosis destroyed lung and inserted but failed to resolve completely the pneumothorax BPF, OLV at dependent lung was impossible. VATS for pneumo- and persistent air leakage remained. The patient had a history thorax under cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was decided after of pulmonary tuberculosis, 16 years ago. -

SJH Procedures

SJH Procedures - Thoracic Service New Name Old Name CPT Code Service BIOPSY OR EXCISION, LESION, FACE AND NECK, 2 OR MORE EXCISE/BIOPSY (MASS/LESION/LIPOMA/CYST) MULTIPLE FACE/NECK 11102 Tangential biopsy of skin (eg, shave, scoop, saucerize, curette); General, Gynecology, single lesion Aesthetics, Urology, Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11103 Tangential biopsy of skin (eg, shave, scoop, saucerize, curette); General, Gynecology, each separate/additional lesion (list separately in addition to Aesthetics, Urology, code for primary procedure) Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11104 Punch biopsy of skin (including simple closure, when General, Gynecology, performed); single lesion Aesthetics, Urology, Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11105 Punch biopsy of skin (including simple closure, when General, Gynecology, performed); each separate/additional lesion (list separately in Aesthetics, Urology, addition to code for primary procedure) Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11106 Incisional biopsy of skin (eg, wedge) (including simple closure, General, Gynecology, when performed); single lesion Aesthetics, Urology, Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11107 Incisional biopsy of skin (eg, wedge) (including simple closure, General, Gynecology, when performed); each separate/additional lesion (list Aesthetics, Urology, separately -

1550 the Preoperative Evaluation of Patients

Pretreatment Assessment of the Lung Resection Candidate Peter Mazzone Disclosures § None related to the content of this talk. Case 1 § 50 year old man diagnosed with a stage IIIA squamous cell cancer of the right upper lobe (N2 involvement) was treated with definitive chemoradiation. § Cancer has persisted at the tumor site. Restaging suggests no nodal involvement. He has received maximal doses of radiation. § He feels he could walk at least 1/2 mile. He rides a bicycle with his 11 year old grandson, perhaps 10-12 city blocks. He has a chronic cough and recently an episode of frank hemoptysis. § He is a former smoker with known COPD receiving an ICS/LABA and LAMA for maintenance therapy. He does not have known cardiac risks. Case 1 § PFTs - FEV1 1.38L, 39% predicted; DLCO 20.6, 70% predicted Which statement is most correct about his preoperative evaluation? A. He should have a cardiac stress test. B. Segment methods for calculating predicted post-operative values will be more accurate than perfusion methods. C. He should have some form of exercise test. D. He should participate in pulmonary rehab prior to surgery. Case 2 § A 70 year old smoker is seen with a localized adenocarcinoma of the lung. She currently feels well, exercising regularly without limitation from excessive dyspnea. § She is an active smoker, down to 1 cigarette per week. § She has been diagnosed with emphysema and started using maintenance tiotropium within the year. § She developed a severe influenza infection 8 months ago. She required hospitalization and was discharged with home oxygen for 3 weeks.