Key Concepts of Gambit Play Yuri Razuvaev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Floridachess Summer 2019

Summer 2019 GM Olexandr Bortnyk wins the 26th Space Coast Open FCA BOARD OF DIRECTORS [term till] kqrbn Contents KQRBN President Kevin J. Pryor (NE) [2019] Editor Speaks & President’s Message .................................................................... 3 Jacksonville, FL [email protected] FCA’s Membership Growth .......................................................................................... 4 FCA Elections ....................................................................................................................... 4 Vice President Ukrainian Takes Over Space Coast Open by Peter Dyson .................................. 5 Stephen Lampkin (NE) [2019] Port Orange, FL Space Coast Open Brilliancy Prize winners by Javad Maharramzade .............. 5 [email protected] 2019 CFCC Sunshine Open by Steven Vigil ............................................................... 10 by Miguel Ararat ................................................. Secretary Some games from recent events 12 Bryan Tillis (S) [2019] A game from the 26th Space Coast Open ............................................................. 16 West Palm Beach, FL Meet the Candidates .........................................................................................................19 [email protected] 2019 FCA Voting Procedures .......................................................................................19 Treasurer 2019 Queen’s Cup Challenge by Kevin Pryor .............................................................. 20 Scott -

A Book About Razuvaev.Indb

Compiled by Boris Postovsky Devoted to Chess The Creative Heritage of Yuri Razuvaev New In Chess 2019 Contents Preface – From the compiler . 7 Foreword – Memories of a chess academic . 9 ‘Memories’ authors in alphabetical order . 16 Chapter 1 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – I . 17 Garry Kasparov . 17 Anatoly Karpov . 19 Boris Spassky . 20 Veselin Topalov . .22 Viswanathan Anand . 23 Magnus Carlsen . 23 Boris Postovsky . 23 Chapter 2 – Selected games . 43 1962-1973 – the early years . 43 1975-1978 – grandmaster . 73 1979-1982 – international successes . 102 1983-1986 – expert in many areas . 138 1987-1995 – always easy and clean . 168 Chapter 3 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – II . 191 Evgeny Tomashevsky . 191 Boris Gulko . 199 Boris Gelfand . 201 Lyudmila Belavenets . 202 Vladimir Tukmakov . .202 Irina Levitina . 204 Grigory Kaidanov . 206 Michal Krasenkow . 207 Evgeny Bareev . 208 Joel Lautier . 209 Michele Godena . 213 Alexandra Kosteniuk . 215 5 Devoted to Chess Chapter 4 – Articles and interviews (by and with Yuri Razuvaev) . 217 Confessions of a grandmaster . 217 My Gambit . 218 The Four Knights Opening . 234 The gambit syndrome . 252 A game of ghosts . 258 You are right, Monsieur De la Bourdonnais!! . 267 In the best traditions of the Soviet school of chess . 276 A lesson with Yuri Razuvaev . 283 A sharp turn . 293 Extreme . 299 The Botvinnik System . 311 ‘How to develop your intellect’ . 315 ‘I am with Tal, we all developed from Botvinnik . ’. 325 Chapter 5 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – III . .331 Igor Zaitsev . 331 Alexander Nikitin . 332 Albert Kapengut . 332 Alexander Shashin . 335 Boris Zlotnik . 337 Lev Khariton . 337 Sergey Yanovsky . -

FIDE Trainers Committee V22.1.2005

FIDE Training! Don’t miss the action! by International Master Jovan Petronic Chairman, FIDE Computer & Internet Chess Committee In 1998 FIDE formed a powerful Committee comprising of leading chess trainers around the chess globe. Accordingly, it was named the FIDE Trainers Committee, and below, I will try to summarize the immense useful information for the readers, current major chess training activities and appeals of the Committee, etc. Among their main tasks in the period 1998-2002 were FIDE licensing of chess trainers and the recognition of these by the International Olympic Committee, benefiting in the long run, to all chess federations, trainers and their students. The proven benefits of playing and studying chess have led to countries, such as Slovenia, introducing chess into their compulsory school curiccullum! The ASEAN Chess Academy, headed by FIDE Vice President, FM, IA & IO - Ignatius Leong, has organized from November 7th to 14th 2003 - a Training Course under the auspices of FIDE and the International Olympic Committee! IM Nikola Karaklajic from Serbia & Montenegro provided the training. The syllabus was targeted for middle and lower levels. At the time, the ASEAN Chess Academy had a syllabus for 200 lessons of 90 minutes each! I am personally proud of having completed such a Course in Singapore. You may view the official Certificate I received here. Another Trainers’ Course was conducted by FIDE and the Asean Chess Academy from 12th to 17th December 2004! Extensive testing was done, here is the list of the candidates who had passed the FIDE Trainer high criteria! The main lecturer was FIDE Senior Trainer Israel Gelfer. -

Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion

Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion Isaak & Vladimir Linder Foreword by Andy Soltis Game Annotations by Karsten Müller World Chess Champions Series 2020 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 Mikhail Botvinnik Sixth World Chess Champion ISBN: 978-1-949859-16-4 (print) ISBN: 949859-17-1 (eBook) © Copyright 2020 Vladimir Linder All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Janel Lowrance Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Foreword by Andy Soltis Signs and Symbols Everything about the World Championships Prologue Chapter 1 His Life and Fate His Childhood and Youth His Family His Personality His Student Life The Algorithm of Mastery The School of the Young and Gifted Political Survey Guest Appearances Curiosities The Netherlands Great Britain Chapter 2 Matches, Tournaments, and Opponents AVRO Tournament, 1938 Alekhine-Botvinnik: The Match That Did Not Happen Alekhine Memorial, 1956 Amsterdam, 1963 and 1966 Sergei Belavienets Isaak Boleslavsky Igor Bondarevsky David Bronstein Wageningen, 1958 Wijk aan Zee, 1969 World Olympiads -

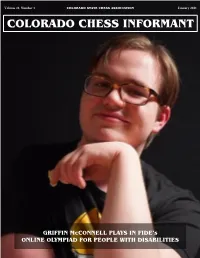

January 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 1 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION January 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT GRIFFIN McCONNELL PLAYS IN FIDE’s ONLINE OLYMPIAD FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES Volume 48, Number 1 Colorado Chess Informant January 2021 From the Editor And so we begin the New Year with renewed hope that can only arrive none too soon... Hello everyone and Happy New Year! I hope that you have en- joyed the holiday season as much as you can and that you are safe and as happy as can be. I understand that a few of our fellow The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a Colorado chess players have been afflicted with Covid-19 but as Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- I understand, they are all on the road to recovery or have already tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are healed up and are back at life full tilt. tax deductible. As you can read in this issue, the CSCA Board of Directors are Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) working hard to at least plan on having some in-person tourna- memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to ments held this year. We all hope that it does indeed come to additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- pass - so stay tuned. tic tournament membership is available for $3. The lead story in this issue is about a remarkable young man and ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the his wonderful play at FIDE’s Online Olympiad for People with email address [email protected]. -

NEWSLETTER 68 (March 26, 2012)

NEWSLETTER 68 (March 26, 2012) EUROPEAN CHESS UNION WON THE COURT CASE AGAINST TURKISH CHESS FEDERATION IN CAS In October 2011, the Turkish Chess Federation filed an Appeal at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) against the decision of the ECU concerning the award of competitions during the bidding procedure for 2013. According to the Appeal by the Turkish Chess Federation, the decision to award the European Youth Championship 2013 to the organizer from Budva, Montenegro was illegal. Also, the Appellant believed that they should have been awarded the organization of the European Senior Team Championship 2013 directly. In the arbitration between the Turkish Chess Federation and the European Chess Union, the CAS and the Panel of three Arbitrators presided by Mr. Robert Reid from England delivered the Arbitral Award on March 22, 2012. The Appeal filed by the Turkish Chess Federation was dismissed, while the decisions made by the European Chess Union Board were accepted as valid. In addition, according to CAS, ‘the costs of the arbitration... shall be borne by the Appellant’. You can download the complete Arbitral Award from the ECU web site. Official web site: http://www.europechess.net/ © Europechess.net Page 1 EUROPEAN CHESS UNION BOARD MEETING IN PLOVDIV The European Chess Union Board meeting was held in "Novotel" hotel in Plovdiv during the European Individual Chess Championship. The main topic of the meeting was the endorsement of the Written Declaration ‘Chess in School’ in the European Parliament. ECU President Silvio Danailov thanked the Board members and others who helped the Declaration to be adopted. -

July 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 3 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION July 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT BACK TO “NEARLY NORMAL” OVER-THE-BOARD PLAY Volume 48, Number 3 Colorado Chess Informant July 2021 From the Editor Slowly, we are getting there... Only fitting that the return to over-the-board tournament play in Colorado resumed with the Senior Open this year. If you recall, that was the last over-the-board tournament held before we went into lockdown last year. You can read all about this year’s offer- The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a ing on page 12. Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- The Denver Chess Club has resumed activity (read the resump- tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are tive result on page 8) with their first OTB tourney - and it went tax deductible. like gang-busters. So good to see. They are also resuming their Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) club play in August. Check out the latest with them at memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to www.DenverChess.com. additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- And if you look at the back cover you will see that the venerable tic tournament membership is available for $3. Colorado Open has returned in all it’s splendor! Somehow I ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the think that this maybe the largest turnout so far - just a hunch on email address [email protected]. my part as players in this state are so hungry to resume the tour- ● Send pay renewals & memberships to the CSCA. -

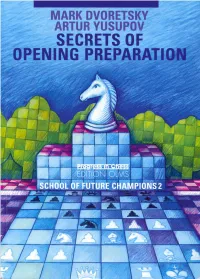

Sfc-2-Opening-Preparation.Pdf

Dvoretsky I Yusupov · Secrets of Opening Preparation PrOgressinCfiess Volume 23 of the ongoing series Editorial board GM Victor Korchnoi GM Helmut Pfleger GM Nigel Short GM Rudolf Teschner 2007 EDITION OLMS m Mark Dvoretsky and Artur Yusupov Secrets of Opening Preparation School of Future Champions 2 Edited and translated by Ken Neat 2007 EDITION OLMS m 4 Books by the same authors: MarkDvorefsky, Artur Yusupov, School of Future Champions Vol. 1 : Secretsof Chess Training ISBN 978-3-283-00515-3 Available Vol. 2: Secretsof Opening Preparation ISBN 978-3-283-00516-0 Available Vol. 3: Secretsof Endgame Technique ISBN 978-3-283-00517-7 In Preparation Vol. 4: Secretsof Positional Play ISBN 978-3-283-00518-4 In Preparation Vol. 5: Secretsof Creative Thinking ISBN 978-3-283-00519-1 In Preparation Mark Dvorefsky, School of Chess Excellence Vol. 1 : Endgame Analysis ISBN 978-3-283-00416-3 Available Vol. 2: Tactical Play ISBN 978-3-283-00417-0 Available Vol. 3: Strategic Play ISBN 978-3-283-00418-7 Available Vol. 4: Opening Developments ISBN 978-3-283-00419-4 Available Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2007 Edition Olms AG Willikonerstr. 1 0 · CH-8618 Oetwil a. S./Zurich E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.edition-olms.com All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not. by way of trade or otherwise. be lent. re-sold. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 21/04/2019 15:32 Page 3

01-01 Cover_Layout 1 22/04/2019 18:18 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 21/04/2019 15:32 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Aditya Munshi ................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine The Nottingham teenager certainly enjoys his chess Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk A Silver Lining........................................................................................................8 Russia won the World Team Championship and England also shone Subscription Rates: United Kingdom Forthcoming Events.........................................................................................20 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Will you be playing chess over either Bank Holiday weekend? 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 The Old and the New .......................................................................................22 Europe Hikaru Nakamura and Jennifer Yu triumphed at the U.S. Championships 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Manx Derailed.....................................................................................................24 3 year (36 issues) £165 Guildford -

LLOYDS BANK MASTERS Strong Open Swiss System Tournament

LLOYDS BANK MASTERS Strong Open swiss system tournament series sponsored by Lloyds Bank, United Kingdom, organised during each summer in London from 1977 to 1994. Year Champion Country Points 1977 Miguel Ángel Quinteros, clear first Argentina 8/10 1978 John Peters, on tie-break USA 7'5/10 1979 Murray Chandler, on tie-break England 7/9 1980 Florin Gheorghiu, on tie-break Romania 7/9 1981 Raymond Keene, on tie-break England 7/9 1982 Anthony Miles, on tie-break England 7/9 1983 Yuri Razuvaev, on tie-break USSR 7/9 1984 John Nunn, on tie-break England 7/9 1985 Alexander Beljavsky, clear first USSR 7'5/9 1986 Simen Adgestein, clear first Norway 8/9 1987 Michael Wilder, after play-off USA 8/10 1988 Gary Lane, after play-off England 8/10 1989 Zurab Azmaiparashvilli, clear first USSR 8‘5/10 1990 Stuart Conquest, on tie-break USSR 8/10 1991 Alexei Shirov, clear first Latvia 8/10 1992 Jonathan Speelman, on tie-break England 8/10 1993 Jonathan Speelman, clear first England 8'5/10 1994 Alexander Morozevich, clear first Russia 9'5/10 http://www.ajedrezdeataque.com/05%20Palmares/Torneos/Europa/Lloyds.htm Note: Sometimes shared winners (for full list, see further below), in case of a tie, mostly the Buchholz tie-break score was used, but in some years, a speed play-off between the two leading players had been organised. In the first two editions1977 & 1978, and again from 1987 on, ten rounds had been played at the Lloyds Bank Masters, from 1979 to 1986, the Open was organized with nine rounds (swiss system). -

GENEVA-GENEVE Major City of Switzerland On

GENEVA-GENEVE Major city of Switzerland on the bank of the Lac Léman (Lake Geneva). Alekhine, Pachman, Korchnoi, Ivkov, Larsen, Spassky, Portisch, Hort, Torre, Timman, Miles, Kasparov, Short, Gelfand, Anand, Adams, Topalov, Kramnik, Svidler, Judit Polgar, Aronian, Bacrot, Grischuk, Eljanov, Alexandra Kosteniuk, Mamedyarov, Radjabov, Nakamura, or Hou Yifan (listed by order of birth) engaged in various events: Simul, Candidate's match, GP, Invitation tournament, Open series, Women, Youth, Rapid, Blitz, Team The Geneva chess history starts with simultaneous chess displays of Alexander Alekhine in 1925, 1928 and 1933: Tribune de Genève, 27-28 September 1925. Alekhine 48 parties simultanées (courtesy of Edward Winter, Chess Notes 6613): https://en.chessbase.com/post/edward-winter-s-che-explorations-69- *** In 1977, Geneva was organizing the FIDE Candidate’s semi-final match Boris Spassky (USSR) vs. Lajos Portisch (Hun) 8½-6½ http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chess.pl?tid=84495 The same year in 1977, Geneva hosted an international invitation tournament (‘Méditerranée’): Bent Larsen won: http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chesscollection?cid=1028672 • 1977 Méditerranée-Turnier in Genf Sieger Larsen, vor 2. Andersson, 3./4. Sosonko, Dzindzichashvili, 5./6. Pachman, Torre, ferner ua. Ivkov, Timman, F. Olafsson, Westerinen, Werner Hug (14 Spieler). Als Chefschiedsrichter wurde der legendäre belgisch-amerikanische Schachspieler und Turnierorganisator George Koltanowski verpflichtet, zu Turnierzeitpunkt auch amtierender Präsident der USCF (US Chess Federation), der britische Schachspieler und Schiedsrichter (und im Zweiten Weltkrieg Codeknacker Enigma-Entschlüsseler) Harry Golombek amtierte als sein Assistent. Im Turniersaal herrschte eine beinahe religiöse Andacht. Da sich der Kandidaten-Viertelfinal Kortschnoi gegen Petrosian zeitlich hinzog, konnte Viktor Kortschnoi nicht wie ursprünglich geplant mitspielen, er spielte anschliessend in Montreux. -

NEWSLETTER 68 (March 26, 2012)

NEWSLETTER 68 (March 26, 2012) EUROPEAN CHESS UNION WON THE COURT CASE AGAINST TURKISH CHESS FEDERATION IN CAS In October 2011, the Turkish Chess Federation filed an Appeal at the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) against the decision of the ECU concerning the award of competitions during the bidding procedure for 2013. According to the Appeal by the Turkish Chess Federation, the decision to award the European Youth Championship 2013 to the organizer from Budva, Montenegro was illegal. Also, the Appellant believed that they should have been awarded the organization of the European Senior Team Championship 2013 directly. In the arbitration between the Turkish Chess Federation and the European Chess Union, the CAS and the Panel of three Arbitrators presided by Mr. Robert Reid from England delivered the Arbitral Award on March 22, 2012. The Appeal filed by the Turkish Chess Federation was dismissed, while the decisions made by the European Chess Union Board were accepted as valid. In addition, according to CAS, ‘the costs of the arbitration... shall be borne by the Appellant’. You can download the complete Arbitral Award from the ECU web site. Official web site: http://www.europechess.net/ © Europechess.net Page 1 EUROPEAN CHESS UNION BOARD MEETING IN PLOVDIV The European Chess Union Board meeting was held in "Novotel" hotel in Plovdiv during the European Individual Chess Championship. The main topic of the meeting was the endorsement of the Written Declaration ‘Chess in School’ in the European Parliament. ECU President Silvio Danailov thanked the Board members and others who helped the Declaration to be adopted.