It's All in the Mindset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Pages

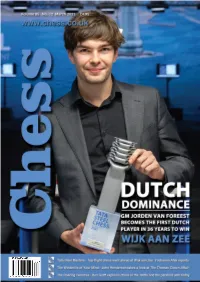

01-01 Cover -March 2021_Layout 1 17/02/2021 17:19 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/02/2021 09:47 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Jorden van Foreest.......................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with the man of the moment after Wijk aan Zee Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Dutch Dominance.................................................................................................8 The Tata Steel Masters went ahead. Yochanan Afek reports Subscription Rates: United Kingdom How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Daniel King presents one of the games of Wijk,Wojtaszek-Caruana 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 Up in the Air ........................................................................................................21 Europe There’s been drama aplenty in the Champions Chess Tour 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Howell’s Hastings Haul ...................................................................................24 3 year (36 issues) £165 David Howell ran -

Game Changer

Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan Game Changer AlphaZero’s Groundbreaking Chess Strategies and the Promise of AI New In Chess 2019 Contents Explanation of symbols 6 Foreword by Garry Kasparov �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Introduction by Demis Hassabis 11 Preface 16 Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 19 Part I AlphaZero’s history . 23 Chapter 1 A quick tour of computer chess competition 24 Chapter 2 ZeroZeroZero ������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 33 Chapter 3 Demis Hassabis, DeepMind and AI 54 Part II Inside the box . 67 Chapter 4 How AlphaZero thinks 68 Chapter 5 AlphaZero’s style – meeting in the middle 87 Part III Themes in AlphaZero’s play . 131 Chapter 6 Introduction to our selected AlphaZero themes 132 Chapter 7 Piece mobility: outposts 137 Chapter 8 Piece mobility: activity 168 Chapter 9 Attacking the king: the march of the rook’s pawn 208 Chapter 10 Attacking the king: colour complexes 235 Chapter 11 Attacking the king: sacrifices for time, space and damage 276 Chapter 12 Attacking the king: opposite-side castling 299 Chapter 13 Attacking the king: defence 321 Part IV AlphaZero’s -

In This Issue

CHESS MOVES The newsletter of the English Chess Federation | 6 issues per year | May/June 2015 John Nunn, Keith Arkell and Mick Stokes at the 15th European Senior Chess Championships - John with his Silver Medal and Keith with his Bronze for the Over 50s section IN THIS ISSUE - ECF News 2-4 Calendar 14-16 Tournament Round-Up 5-6 Supplement --- Junior Chess 6-8 Simon Williams S7 Euro Seniors 9-10 Readers’ Letters S36 National Club 10 Never Mind the GMs S44 Grand Prix 11-12 Home News S52-53 Book Reviews 13 1 ECF NEWS The Chess Trust The Chess Trust has now been approved by the Charity Commission as registered charity no. 1160881. This will be the charitable arm of the ECF with wide ranging charitable purposes to support the provision and development of chess within England. This is good news There is still work to be done to enable the Trust to become operational, which the trustees will address over the next few months. The initial trustees are Ray Edwards, Keith Richardson, Julian Farrand, Phil Ehr and David Eustace. Questions about the Trust can be raised on the ECF Forum at http://www.englishchess.org.uk/Forum/view- topic.php?f=4&t=261 FIDE – ECF meeting report FIDE President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, ECF President Dominic Lawson and Russian Chess Federation President Andrei Filatov met in London on 11 March 2015. The other ECF participants were Chief Executive Phil Ehr and FIDE Delegate Malcolm Pein. The other FIDE participants were Assistant to the FIDE President Barik Balgabaev and Secretary of FIDE’s Chess in Schools Commission Sainbayar Tserendorj, who is also the founder and ECF Council member for the UK Chess Academy. -

Floridachess Summer 2019

Summer 2019 GM Olexandr Bortnyk wins the 26th Space Coast Open FCA BOARD OF DIRECTORS [term till] kqrbn Contents KQRBN President Kevin J. Pryor (NE) [2019] Editor Speaks & President’s Message .................................................................... 3 Jacksonville, FL [email protected] FCA’s Membership Growth .......................................................................................... 4 FCA Elections ....................................................................................................................... 4 Vice President Ukrainian Takes Over Space Coast Open by Peter Dyson .................................. 5 Stephen Lampkin (NE) [2019] Port Orange, FL Space Coast Open Brilliancy Prize winners by Javad Maharramzade .............. 5 [email protected] 2019 CFCC Sunshine Open by Steven Vigil ............................................................... 10 by Miguel Ararat ................................................. Secretary Some games from recent events 12 Bryan Tillis (S) [2019] A game from the 26th Space Coast Open ............................................................. 16 West Palm Beach, FL Meet the Candidates .........................................................................................................19 [email protected] 2019 FCA Voting Procedures .......................................................................................19 Treasurer 2019 Queen’s Cup Challenge by Kevin Pryor .............................................................. 20 Scott -

A Book About Razuvaev.Indb

Compiled by Boris Postovsky Devoted to Chess The Creative Heritage of Yuri Razuvaev New In Chess 2019 Contents Preface – From the compiler . 7 Foreword – Memories of a chess academic . 9 ‘Memories’ authors in alphabetical order . 16 Chapter 1 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – I . 17 Garry Kasparov . 17 Anatoly Karpov . 19 Boris Spassky . 20 Veselin Topalov . .22 Viswanathan Anand . 23 Magnus Carlsen . 23 Boris Postovsky . 23 Chapter 2 – Selected games . 43 1962-1973 – the early years . 43 1975-1978 – grandmaster . 73 1979-1982 – international successes . 102 1983-1986 – expert in many areas . 138 1987-1995 – always easy and clean . 168 Chapter 3 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – II . 191 Evgeny Tomashevsky . 191 Boris Gulko . 199 Boris Gelfand . 201 Lyudmila Belavenets . 202 Vladimir Tukmakov . .202 Irina Levitina . 204 Grigory Kaidanov . 206 Michal Krasenkow . 207 Evgeny Bareev . 208 Joel Lautier . 209 Michele Godena . 213 Alexandra Kosteniuk . 215 5 Devoted to Chess Chapter 4 – Articles and interviews (by and with Yuri Razuvaev) . 217 Confessions of a grandmaster . 217 My Gambit . 218 The Four Knights Opening . 234 The gambit syndrome . 252 A game of ghosts . 258 You are right, Monsieur De la Bourdonnais!! . 267 In the best traditions of the Soviet school of chess . 276 A lesson with Yuri Razuvaev . 283 A sharp turn . 293 Extreme . 299 The Botvinnik System . 311 ‘How to develop your intellect’ . 315 ‘I am with Tal, we all developed from Botvinnik . ’. 325 Chapter 5 – Memories of Razuvaev’s contemporaries – III . .331 Igor Zaitsev . 331 Alexander Nikitin . 332 Albert Kapengut . 332 Alexander Shashin . 335 Boris Zlotnik . 337 Lev Khariton . 337 Sergey Yanovsky . -

London Chess Classic, Round 2

PRESS RELEASE London Chess Classic, Round 2 WINTER DRAWS ON John Saunders reports: The second round of the 9th London Chess Classic saw the tournament migrate back to its familiar home at the Olympia Conference Centre, West London, after the brief dalliance with Google’s London HQ in Pancras Square. Round three takes place on Monday 4 December, but at the changed time of 16.00 London time. “We meet again, Mr Karjakin!” The 2016 world championship opponents renew their rivalry. (Photo John Saunders) As Maurice Ashley put it, quoting an earlier US sports commentator, "it was déjà vu all over again." First to finish were Magnus Carlsen and Sergey Karjakin who concluded hostilities on move 30. The first movement of the oeuvre was Giuoco Piano, the second pianissimo, the third molto doloroso and the fourth whatever the Italian is for non- existent. The score of this game may be examined on our website but is one for devoted chessologists only. I don't propose to do much more than hum the main theme. Contradicting what Emperor Joseph said in the film Amadeus, I felt there were not enough notes. Understandable, perhaps, that Carlsen and Karjakin should be sick of staring across the board at their opponent's coat of many sponsors’ colours. I'll confine myself to one second-hand comment: super-GM emeritus Jon Speelman, watching from the VIP Room, thought 21.f4 might have given White a little something. He was speaking without benefit of silicon, as he always does, but the engines agreed with him. The idea was to open up the e-file for White's rooks. -

Qualifiers for the British Championship 2020 (Last Updated 14Th November 2019)

Qualifiers for the British Championship 2020 (last updated 14th November 2019) Section A: Qualification from the British Championship A1. British Champions Jacob Aagaard (B1), Michael Adams (A3, B1, C), Leonard Barden (B3), Robert Bellin (B3), George Botterill (B3), Stuart Conquest (B1), Joseph Gallagher (B1), William Hartston (B3), Jonathan Hawkins (A3, B1), Michael Hennigan (B3), Julian Hodgson (B1), David Howell (A3, B1), Gawain Jones (A3, B1), Raymond Keene (B1), Peter Lee, Paul Littlewood (B3), Jonathan Mestel (B1), John Nunn (B1), Jonathan Penrose (B1), James Plaskett (B1), Jonathan Rowson (B1), Matthew Sadler (B1), Nigel Short (B1), Jon Speelman (B1), Chris Ward (A3, B1), William Watson (B1), A2. British Women’s Champions Ketevan Arakhamia-Grant (B1, B2), Jana Bellin (B2), Melanie Buckley, Margaret Clarke, Joan Doulton, Amy Hoare, Jovanka Houska (A3, B2, B3), Harriet Hunt (B2, B3), Sheila Jackson (B2), Akshaya Kalaiyalahan, Susan Lalic (B2, B3), Sarah Longson, Helen Milligan, Gillian Moore, Dinah Norman, Jane Richmond (B6), Cathy Forbes (B4), A3. Top 20 players and ties in the 2018 British Championship Luke McShane (C), Nicholas Pert (B1), Daniel Gormally (B1), Daniel Fernandez (B1), Keith Arkell (A8, B1), David Eggleston (B3), Tamas Fodor (B1), Justin Hy Tan (A5), Peter K Wells (B1), Richard JD Palliser (B3), Lawrence Trent (B3), Joseph McPhillips (A5, B3), Peter T Roberson (B3), James R Adair (B3), Mark L Hebden (B1), Paul Macklin (B5), David Zakarian (B5), Koby Kalavannan (A6), Craig Pritchett (B5) A4. Top 10 players and ties in the 2018 Major Open Thomas Villiers, Viktor Stoyanov, Andrew P Smith, Jonah B Willow, Ben Ogunshola, John G Cooper, Federico Rocco (A7), Robert Stanley, Callum D Brewer, Jacob D Yoon, Jagdish Modi Shyam, Aron Teh Eu Wen, Maciej Janiszewski A5. -

British Knockout Chess Championship

PRESS RELEASE BRITISH KNOCKOUT CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP John Saunders reports: The 3rd British Knockout Championship takes place alongside the London Chess Classic from 1-9 December 2017, featuring most of the leading grandmasters from the UK plus the winner of the 4NCL Open held over the weekend of 3-5 November in Coventry. Pairings (The first named player has White in Game 1) Quarter Finals 1 Nigel Short v Alan Merry 2 Matthew Sadler v Jonathan Rowson 3 David Howell v Jonathan Hawkins 4 Gawain Jones v Luke McShane Semi Finals 1 Winner Quarter Final 1 v Winner Quarter Final 4 2 Winner Quarter Final 3 v Winner Quarter Final 2 Final Winner Semi Final 2 v Winner Semi Final 1 In the Final the colours will be reversed after the four Standardplay games, so that the winner of Semi Final 2 will have White in Games 1 and 3 (Standardplay) and Black in Games 5 and 7 (Rapid). A draw for colours in each match was performed on Tuesday 28th November at Chess and Bridge under the supervision of Malcolm Pein. Players were seeded based on their rating as at 1 November 2017, with Nigel Short placed ahead of Matthew Sadler based on his greater number of games played. Nigel Short returns as the reigning British Knockout Champion, having defeated Daniel Fernandez, Luke McShane and then David Howell in last year’s competition to claim the first prize of £20,000. Most grandmasters start drifting away from the game in their fifties but Nigel shows no sign of slackening the pace of his globe- trotting chess career. -

The Queen's Gambit

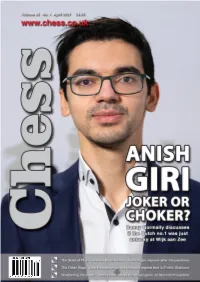

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

Newsletter 2

http://sut5.co.uk/l/c.php?c=33538&ct=81709 The English Chess Federaon eNewsleer HEADLINE NEWS --- Michael Adams enters the British Chess Championships See the arcle on the Brish in the “Forthcoming Events secon for further details ... Already the second edition of the ECF eNewsletter, and we were pleased with the response we got for the first one! It will be sent out on the 24th of each month to anyone for whom we have an email address*. We experienced a few distribution gremlins the first time around but we think we have it mostly sorted out this time. Nonetheless, if you did not find your eNewletter in either your inbox or spam, please email us at [email protected] . You'll also be able to access the eNewsletter via a link on the ECF website ... If you have any chess news you think we should know about, or if you have any comments you would like to make on this newsletter, do contact us at [email protected] ... the deadline for the newsletter will normally be on the 18th of each month, so don’t send us the info too late! --- Mark Jordan, Publicity Manager Email: [email protected] * If you don’t want to receive the eNewsle er you can ck the opt-out box at the bo om of the email. If, on the other hand, we haven’t got your email address, you’ve somehow managed to see this anyway and you’d like to receive it regularly, contact us at o'ce(englishchess.org.uk and we’ll put you on the list and also email you if there is anything else we think you might like to know. -

Chess Moves.Qxp

ChessChess MovesMoveskk ENGLISH CHESS FEDERATION | MEMBERS’ NEWSLETTER | July 2013 EDITION InIn thisthis issueissue ------ 100100 NOTNOT OUT!OUT! FEAFEATURETURE ARARTICLESTICLES ...... -- thethe BritishBritish ChessChess ChampionshipsChampionships 4NCL4NCL EuropeanEuropean SchoolsSchools 20132013 -- thethe finalfinal weekendweekend -- picturespictures andand resultsresults GreatGreat BritishBritish ChampionsChampions TheThe BunrBunrattyatty ChessChess ClassicClassic -- TheThe ‘Absolute‘Absolute ChampionChampion -- aa looklook backback -- NickNick PertPert waswas therethere && annotatesannotates thethe atat JonathanJonathan Penrose’Penrose’ss championshipchampionship bestbest games!games! careercareer MindedMinded toto SucceedSucceed BookshelfBookshelf lookslooks atat thethe REALREAL secretssecrets ofof successsuccess PicturedPictured -- 20122012 BCCBCC ChampionsChampions JovankJovankaa HouskHouskaa andand GawainGawain JonesJones PhotogrPhotographsaphs courtesycourtesy ofof BrendanBrendan O’GormanO’Gorman [https://picasawe[https://picasaweb.google.com/105059642136123716017]b.google.com/105059642136123716017] CONTENTS News 2 Chess Moves Bookshelf 30 100 NOT OUT! 4 Book Reviews - Gary Lane 35 Obits 9 Grand Prix Leader Boards 36 4NCL 11 Calendar 38 Great British Champions - Jonathan Penrose 13 Junior Chess 18 The Bunratty Classic - Nick Pert 22 Batsford Competition 29 News GM Norm for Yang-Fang Zhou Congratulations to 18-year-old Yang-Fan Zhou (far left), who won the 3rd Big Slick International (22-30 June) GM norm section with a score of 7/9 and recorded his first grandmaster norm. He finished 1½ points ahead of GMs Keith Arkell, Danny Gormally and Bogdan Lalic, who tied for second. In the IM norm section, 16-year-old Alan Merry (left) achieved his first international master norm by winning the section with an impressive score of 7½ out of 9. An Englishman Abroad It has been a successful couple of months for England’s (and the world’s) most travelled grandmaster, Nigel Short. In the Sigeman & Co. -

FIDE Trainers Committee V22.1.2005

FIDE Training! Don’t miss the action! by International Master Jovan Petronic Chairman, FIDE Computer & Internet Chess Committee In 1998 FIDE formed a powerful Committee comprising of leading chess trainers around the chess globe. Accordingly, it was named the FIDE Trainers Committee, and below, I will try to summarize the immense useful information for the readers, current major chess training activities and appeals of the Committee, etc. Among their main tasks in the period 1998-2002 were FIDE licensing of chess trainers and the recognition of these by the International Olympic Committee, benefiting in the long run, to all chess federations, trainers and their students. The proven benefits of playing and studying chess have led to countries, such as Slovenia, introducing chess into their compulsory school curiccullum! The ASEAN Chess Academy, headed by FIDE Vice President, FM, IA & IO - Ignatius Leong, has organized from November 7th to 14th 2003 - a Training Course under the auspices of FIDE and the International Olympic Committee! IM Nikola Karaklajic from Serbia & Montenegro provided the training. The syllabus was targeted for middle and lower levels. At the time, the ASEAN Chess Academy had a syllabus for 200 lessons of 90 minutes each! I am personally proud of having completed such a Course in Singapore. You may view the official Certificate I received here. Another Trainers’ Course was conducted by FIDE and the Asean Chess Academy from 12th to 17th December 2004! Extensive testing was done, here is the list of the candidates who had passed the FIDE Trainer high criteria! The main lecturer was FIDE Senior Trainer Israel Gelfer.