Brazilian Agouti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammal Abundances and Seed Traits Control the Seed Dispersal and Predation Roles of Terrestrial Mammals in a Costa Rican Forest

BIOTROPICA 45(3): 333–342 2013 10.1111/btp.12014 Mammal Abundances and Seed Traits Control the Seed Dispersal and Predation Roles of Terrestrial Mammals in a Costa Rican Forest Erin K. Kuprewicz1 Department of Biology, University of Miami, 1301 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL, 33146, U.S.A. ABSTRACT In Neotropical forests, mammals act as seed dispersers and predators. To prevent seed predation and promote dispersal, seeds exhibit physical or chemical defenses. Collared peccaries (Pecari tajacu) cannot eat some hard seeds, but can digest chemically defended seeds. Central American agoutis (Dasyprocta punctata) gnaw through hard-walled seeds, but cannot consume chemically defended seeds. The objectives of this study were to determine relative peccary and agouti abundances within a lowland forest in Costa Rica and to assess how these two mammals affect the survival of large seeds that have no defenses (Iriartea deltoidea, Socratea exorrhiza), physical defenses (Astrocaryum alatum, Dipteryx panamensis), or chemical defenses (Mucuna holtonii) against seed predators. Mammal abundances were deter- mined over 3 yrs from open-access motion-detecting camera trap photos. Using semi-permeable mammal exclosures and thread-marked seeds, predation and dispersal by mammals for each seed species were quantified. Abundances of peccaries were up to six times higher than those of agoutis over 3 yrs, but neither peccary nor agouti abundances differed across years. Seeds of A. alatum were predomi- nantly dispersed by peccaries, which did not eat A. alatum seeds, whereas non-defended and chemically defended seeds suffered high levels of predation, mostly by peccaries. Agoutis did not eat M. holtonii seeds. Peccaries and agoutis did not differ in the distances they dispersed seeds. -

Carrion Consumption by Dasyprocta Leporina

a http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/bjb.2014.0087 Original Article Carrion consumption by Dasyprocta leporina (RODENTIA: DASYPROCTIDAE) and a review of meat use by agoutis Figueira, L.a, Zucaratto, R.a, Pires, AS.a*, Cid, B.band Fernandez, FAS.b aDepartamento de Ciências Ambientais, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro – UFRRJ, Rodovia BR 465, Km 07, CEP 23890-000, Seropédica, RJ, Brazil bDepartamento de Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ, Av. Carlos Chagas Filho, 373, Bloco A, CCS, Ilha do Fundão, CP 68020, CEP 21941-902, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: August 27, 2012 – Accepted: April 30, 2013 – Distributed: August 31, 2014 Abstract The consumption of the carrion of a tapiti by a reintroduced female Dasyprocta leporina was observed in the wild. Herein, besides describing this event, we reviewed other evidence of vertebrate consumption by agoutis. Most of the studies describing this behaviour have been carried out in captivity. The preyed animals included birds and small rodents, which were sometimes killed by agoutis. This pattern suggests that this is not an anomalous behaviour for the genus, reflecting its omnivorous habits. This behaviour can be a physiologically sound feeding strategy, so new studies should focus on the temporal variation in the consumption of this resource, possibly related to food scarcity periods or to reproductive seasons, when the need for high-quality food tends to increase. Keywords: diet, Rodentia, zoophagy, carrion. Consumo de carniça por Dasyprocta leporina (RODENTIA: DASYPROCTIDAE) e uma revisão do uso de carne por cutias Resumo Foi observado na natureza o consumo da carniça de um tapiti (Sylvilagus brasiliensis) por uma fêmea reintroduzida da cutia Dasyprocta leporina. -

Red-Rumped Agouti)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Dasyprocta leporina (Red-rumped Agouti) Family: Dasyproctidae (Agoutis) Order: Rodentia (Rodents) Class: Mammalia (Mammals) Fig. 1. Red-rumped agouti, Dasyprocta leporina. [http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3b/Dasyprocta.leporina-03-ZOO.Dvur.Kralove.jpg, downloaded 12 November 2012] TRAITS. Formerly Dasyprocta aguti, and also known as the Brazilian agouti and as “Cutia” in Brazil and “Acure” in Venezuela. The average Dasyprocta leporina weighs approximately between 3 kg and 6 kg with a body length of about 49-64 cm. They are medium sized caviomorph rodents (Wilson and Reeder, 2005) with brown fur consisting of darker spots of brown covering their upper body and a white stripe running down the centre of their underside (Eisenberg, 1989). Show sexual dimorphism as the males are usually smaller in size than the females but have a similar appearance (Wilson and Reeder, 2005). Locomotion is quadrupedal. Forefeet have four toes while hind feet (usually longer than forefeet) have 3. Small round ears with short hairless tail not more than 6 cm in length (Dubost 1998). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour ECOLOGY. Dasyprocta leporina is found in the tropical forests of Trinidad and conserved in the Central Range Wildlife Sanctuary at the headwaters of the Tempuna and Talparo watersheds in central Trinidad (Bacon and Ffrench 1972). They are South American natives and are distributed widely in Venezuela, French Guiana and Amazon forests of Brazil (Asquith et al. 1999; Dubost 1998). Has widespread distribution in the Neotropics (Eisenberg 1989; Emmons and Feer 1997). -

Panthera Onca) Distribution, Density, and Movement in the Brazilian Pantanal

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Dissertations and Theses 6-10-2019 Drivers of jaguar (Panthera onca) distribution, density, and movement in the Brazilian Pantanal Allison Devlin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Devlin, Allison, "Drivers of jaguar (Panthera onca) distribution, density, and movement in the Brazilian Pantanal" (2019). Dissertations and Theses. 114. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds/114 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DRIVERS OF JAGUAR (PANTHERA ONCA) DISTRIBUTION, DENSITY, AND MOVEMENT IN THE BRAZILIAN PANTANAL by Allison Loretta Devlin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York June 2019 Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Approved by: Jacqueline L. Frair, Major Professor Stephen V. Stehman, Chair, Examining Committee James P. Gibbs, Examining Committee Jonathan B. Cohen, Examining Committee Peter G. Crawshaw Jr., Examining Committee Luke T.B. Hunter, Examining Committee Melissa K. Fierke, Department Chair S. Scott Shannon, Dean, The Graduate School © 2019 Copyright A.L. Devlin All rights reserved Acknowledgements I am indebted to many mentors, colleagues, friends, and loved ones whose guidance, support, patience, and constructive challenges have carried this project to its culmination. -

Matses Indian Rainforest Habitat Classification and Mammalian Diversity in Amazonian Peru

Journal of Ethnobiology 20(1): 1-36 Summer 2000 MATSES INDIAN RAINFOREST HABITAT CLASSIFICATION AND MAMMALIAN DIVERSITY IN AMAZONIAN PERU DAVID W. FLECK! Department ofEveilltioll, Ecology, alld Organismal Biology Tile Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210-1293 JOHN D. HARDER Oepartmeut ofEvolution, Ecology, and Organismnl Biology Tile Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210-1293 ABSTRACT.- The Matses Indians of northeastern Peru recognize 47 named rainforest habitat types within the G61vez River drainage basin. By combining named vegetative and geomorphological habitat designations, the Matses can distinguish 178 rainforest habitat types. The biological basis of their habitat classification system was evaluated by documenting vegetative ch<lracteristics and mammalian species composition by plot sampling, trapping, and hunting in habitats near the Matses village of Nuevo San Juan. Highly significant (p<:O.OOI) differences in measured vegetation structure parameters were found among 16 sampled Matses-recognized habitat types. Homogeneity of the distribution of palm species (n=20) over the 16 sampled habitat types was rejected. Captures of small mammals in 10 Matses-rc<:ognized habitats revealed a non-random distribution in species of marsupials (n=6) and small rodents (n=13). Mammal sighlings and signs recorded while hunting with the Matses suggest that some species of mammals have a sufficiently strong preference for certain habitat types so as to make hunting more efficient by concentrating search effort for these species in specific habitat types. Differences in vegetation structure, palm species composition, and occurrence of small mammals demonstrate the ecological relevance of Matses-rccognized habitat types. Key words: Amazonia, habitat classification, mammals, Matses, rainforest. RESUMEN.- Los nalivos Matslis del nordeste del Peru reconacen 47 tipos de habitats de bosque lluvioso dentro de la cuenca del rio Galvez. -

Using Allele-Specific

NOTES AND COMMENTS Rapid identification of capybara (Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris) using allele-specific PCR Henrique-Silva, F.*, Cervini, M., Rios, WM., Lusa, AL., Lopes, A., Gonçalves, D., Fonseca, D., Franzin, F., Damalio, J., Scaramuzzi, K., Camilo, R., Ferrarezi, T., Liberato, M., Mortari, N. and Matheucci Jr., E. Departamento de Genética e Evolução, Universidade Federal de São Carlos – UFSCar, Rod. Washington Luiz, Km 235, CEP 13565-905, São Carlos, SP, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received August 11, 2005 – Accepted February 10, 2006 – Distributed February 28, 2007 (With 1 figure) The capybara is the largest rodent in the world and is ments of frozen meat using treatment with proteinase K, widely distributed throughout Central and South America as described in (Sambrook et al., 1989). Basically, the (Paula et al., 1999). It is an animal of economic interest meat fragments were incubated in 400 µL buffer (10 mM due to the pleasant flavor of its meat and higher protein Tris-HCl, pH:7.8; 5 mM EDTA; 0.5% SDS) containing content in comparison to beef and pork meat. The hide, 400 µg of. proteinase K at 65 °C for 2 hours. After that, hair and fat also have economic advantages. Thus, as an the solution was treated with an equal volume of phenol- animal with such high economic potential, it is the target chloroform, and the DNA was purified from the aqueous of hunters, even though hunting capybara is prohibited phase by ethanol precipitation. Approximately 50 ng of by law in Brazil (Fauna Law, number 9.605/98). the DNA was used in amplification reactions containing Due to their similarities, capybara meat is easily 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 8.4; 50 mM KCl; 1.5 mM MgCl2, confused with pork. -

Richness of Plants, Birds and Mammals Under the Canopy of Ramorinoa Girolae, an Endemic and Vulnerable Desert Tree Species

BOSQUE 38(2): 307-316, 2017 DOI: 10.4067/S0717-92002017000200008 Richness of plants, birds and mammals under the canopy of Ramorinoa girolae, an endemic and vulnerable desert tree species Riqueza de plantas, aves y mamíferos bajo el dosel de Ramorinoa girolae, una especie arbórea endémica y vulnerable del desierto Valeria E Campos a,b*, Viviana Fernández Maldonado a,b*, Patricia Balmaceda a, Stella Giannoni a,b,c a Interacciones Biológicas del Desierto (INTERBIODES), Av. I. de la Roza 590 (O), J5402DCS Rivadavia, San Juan, Argentina. *Corresponding author: b CIGEOBIO, UNSJ CONICET, Universidad Nacional de San Juan- CUIM, Av. I. de la Roza 590 (O), J5402DCS Rivadavia, San Juan, Argentina, phone 0054-0264-4260353 int. 402, [email protected], [email protected] c IMCN, FCEFN, Universidad Nacional de San Juan- España 400 (N), 5400 Capital, San Juan, Argentina. SUMMARY Dominant woody vegetation in arid ecosystems supports different species of plants and animals largely dependent on the existence of these habitats for their survival. The chica (Ramorinoa girolae) is a woody leguminous tree endemic to central-western Argentina and categorized as vulnerable. We evaluated 1) richness of plants, birds and mammals associated with the habitat under its canopy, 2) whether richness is related to the morphological attributes and to the features of the habitat under its canopy, and 3) behavior displayed by birds and mammals. We recorded presence/absence of plants under the canopy of 19 trees in Ischigualasto Provincial Park. Moreover, we recorded abundance of birds and mammals and signs of mammal activity using camera traps. -

Dolichotis Patagonum (CAVIOMORPHA; CAVIIDAE; DOLICHOTINAE) Mastozoología Neotropical, Vol

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 ISSN: 1666-0536 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Silva Climaco das Chagas, Karine; Vassallo, Aldo I; Becerra, Federico; Echeverría, Alejandra; Fiuza de Castro Loguercio, Mariana; Rocha-Barbosa, Oscar LOCOMOTION IN THE FASTEST RODENT, THE MARA Dolichotis patagonum (CAVIOMORPHA; CAVIIDAE; DOLICHOTINAE) Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 26, no. 1, 2019, -June, pp. 65-79 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45762554005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 26(1):65-79, Mendoza, 2019 Copyright ©SAREM, 2019 Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 http://www.sarem.org.ar https://doi.org/10.31687/saremMN.19.26.1.0.06 http://www.sbmz.com.br Artículo LOCOMOTION IN THE FASTEST RODENT, THE MARA Dolichotis patagonum (CAVIOMORPHA; CAVIIDAE; DOLICHOTINAE) Karine Silva Climaco das Chagas1, 2, Aldo I. Vassallo3, Federico Becerra3, Alejandra Echeverría3, Mariana Fiuza de Castro Loguercio1 and Oscar Rocha-Barbosa1, 2 1 Laboratório de Zoologia de Vertebrados - Tetrapoda (LAZOVERTE), Departamento de Zoologia, IBRAG, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Maracanã, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Evolução do Instituto de Biologia/Uerj. 3 Laboratorio de Morfología Funcional y Comportamiento. Departamento de Biología; Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras (CONICET); Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata. -

Mammal List of Mindo Lindo

Mammal list of Mindo Lindo Fam. Didelphidae (Opossums) Didelphis marsupialis, Black-eared/ Common Opossum Fam. Soricidae (Shrews) Cryptotis spec Fam. Myrmecophagidae (Anteaters) Tamandua mexicana, Northern Tamandua Fam. Dasypodidae (Armadillos) Dasypus novemcinctus, Nine-banded Armadillo Fam. Megalonychidae (Two-toed sloths) Choloepus hoffmanni, Hoffmann’s two-toed sloth Fam. Cebidae (Cebid monkeys) Cebus capucinus, White-throated Capuchin Fam. Atelidae (Atelid monkeys) Alouatta palliata, Mantled Howler Fam. Procyonidae (Procyonids) Nasua narica, Coati Potos flavus, Kinkajou Bassaricyon gabbii, Olingo Fam. Mustelidae (Weasel Family) Eira barbara, Tayra Mustela frenata, Long-tailed Weasel Fam. Felidae (Cats) Puma concolor, Puma Felis pardalis, Ozelot Fam. Tayassuidae (Peccaries) Tayassu tajacu, Collared Peccary Fam. Cervidae (Deer Family) Odocoileus virginianus, White-tailed Deer Fam. Sciuridae (Squirrels and Marmots) Sciurus granatensis, Neotropical Red Squirrel Fam. Erethizontidae (Porcupines) Coendou bicolor, Bicolor-spined Porcupine Fam. Dasyproctidae (Agoutis) Dasyprocta punctata, Central American Agouti Fam. Phyllostomatidae (New World Leaf-nosed bats) Carollia brevicauda, Silky short-tailed bat Anoura fistulata, Tube-lipped nectar bat Micronycteris megalotis, Little big-eared bat Fam. Vespertilionidae (Vesper bats) Myotis spec. There are far more mammal species in Mindo Lindo but until now we could not identify them for sure (especially the bats and rodents). Systematics follow: Eisenberg, J.F. & K.H. Redford (1999): Mammals of the Neotropics, vol.3. Various Wikipedia articles as well as from the Handbook of the mammals of the world. . -

Relative Rates of Molecular Evolution in Rodents and Their Symbionts

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1997 Relative Rates of Molecular Evolution in Rodents and Their yS mbionts. Theresa Ann Spradling Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Spradling, Theresa Ann, "Relative Rates of Molecular Evolution in Rodents and Their yS mbionts." (1997). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6527. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6527 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. hi the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Ecological Roles and Conservation Challenges of Social, Burrowing

REVIEWS REVIEWS REVIEWS Ecological roles and conservation challenges 477 of social, burrowing, herbivorous mammals in the world’s grasslands Ana D Davidson1,2*, James K Detling3, and James H Brown1 The world’s grassland ecosystems are shaped in part by a key functional group of social, burrowing, herbivorous mammals. Through herbivory and ecosystem engineering they create distinctive and important habitats for many other species, thereby increasing biodiversity and habitat heterogeneity across the landscape. They also help maintain grassland presence and serve as important prey for many predators. However, these burrowing mammals are facing myriad threats, which have caused marked decreases in populations of the best-studied species, as well as cascading declines in dependent species and in grassland habitat. To prevent or mitigate such losses, we recommend that grasslands be managed to promote the compatibility of burrowing mammals with human activities. Here, we highlight the important and often overlooked ecological roles of these burrowing mammals, the threats they face, and future management efforts needed to enhance their populations and grass- land ecosystems. Front Ecol Environ 2012; 10(9): 477–486, doi:10.1890/110054 (published online 28 Sep 2012) rassland ecosystems worldwide are fundamentally Australia (Figure 1). Often living in colonies ranging Gshaped by an underappreciated but key functional from tens to thousands of individuals, these mammals col- group of social, semi-fossorial (adapted to burrowing and lectively transform grassland landscapes through their bur- living underground), herbivorous mammals (hereafter, rowing and feeding activity. By grouping together socially, burrowing mammals). Examples include not only the phy- they also create distinctive habitat patches that serve as logenetically similar species of prairie dogs of North areas of concentrated prey for many predators. -

Counting on Forests and Accounting for Forest Contributions in National

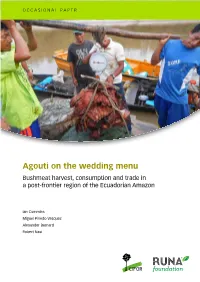

OCCASIONAL PAPER Agouti on the wedding menu Bushmeat harvest, consumption and trade in a post-frontier region of the Ecuadorian Amazon Ian Cummins Miguel Pinedo-Vasquez Alexander Barnard Robert Nasi OCCASIONAL PAPER 138 Agouti on the wedding menu Bushmeat harvest, consumption and trade in a post-frontier region of the Ecuadorian Amazon Ian Cummins Runa Foundation Miguel Pinedo-Vasquez Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Earth Institute Center for Environmental Sustainability (EICES) Alexander Barnard University of California Robert Nasi Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Occasional Paper 138 © 2015 Center for International Forestry Research Content in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-602-387-009-7 DOI: 10.17528/cifor/005730 Cummins I, Pinedo-Vasquez M, Barnard A and Nasi R. 2015. Agouti on the wedding menu: Bushmeat harvest, consumption and trade in a post-frontier region of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Occasional Paper 138. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. Photo by Alonso Pérez Ojeda Del Arco Buying bushmeat for a wedding CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] cifor.org We would like to thank all donors who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund. For a list of Fund donors please see: https://www.cgiarfund.org/FundDonors Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIFOR, the editors, the authors’ institutions, the financial sponsors or the reviewers.