1298 Enacts Paid Sick Leave Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Affordability of Overall Shelter Costs, It Creates Significant Business Risks for the State’S Utilities As Well;

HOME ENERGY AFFORDABILITY GAP: 2011 Connecticut Legislative Districts Prepared for: Operation Fuel Bloomfield, Connecticut Pat Wrice, Executive Director Prepared by: Roger D. Colton Fisher, Sheehan & Colton Public Finance and General Economics Belmont, Massachusetts December 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents………………………………………………………….. i Table of Tables…………………………………………………….……… iii The Home Energy Affordability Gap in Connecticut……………………... 1 Home Energy Affordability Gap Reaches into Moderate Income……....... 3 Home Energy Burdens…………………………………………………….. 5 Federal LIHEAP Coverage……………………………………………....... 6 Basic Family Needs Budgets……………………………………………… 7 What Contributes to the Inability to Meet Basic Needs Budget………… 10 Overall Median Income………………………………………………… 10 Mean Income by Poverty Level………………………………………… 10 The Particular Needs of the Working Poor…………………………….. 11 Impact of Energy Prices on Total Shelter Costs…………………………... 13 The Consequences of Home Energy Unaffordability in 14 Connecticut………………………………………………………………... The “Social Problems” of Home Energy Unaffordability………………. 15 Public Health Implications……………………………………………. 15 Nutrition Implications…………………………………………………. 17 Public Safety Implications…………………………………………….. 19 The Competitiveness of Business and Industry……………………….. 20 Connecticut Home Energy Affordability Gap: 2011 Page i Summary………………………………………………………………. 22 The “Business Problems” of Home Energy Unaffordability……………. 22 Home Energy Burdens and Utility Bill Payment Problems…………... 23 Utility Bill Payment Problems……………………………………….. -

Leaders of the General Assembly

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Joint Committee on Legislative Management wishes to thank Information Technology employee Robert Caroti for the cover photograph of the State Capitol. Also thank you to the legislators and staff who participated in the selection of this year’s photo. LEADERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY SENATE President Pro Tempore, Martin M. Looney Majority Leader, Bob Duff Chief Deputy President Pro Tempore and Federal Relations Liaison, Joseph J. Crisco Jr. Deputy President Pro Tempore, Eric D. Coleman Deputy President Pro Tempore, John Fonfara Deputy President Pro Tempore, Joan Hartley Deputy President Pro Tempore, Carlo Leone Assistant President Pro Tempore, Steve Cassano Assistant President Pro Tempore, Cathy Osten Deputy Majority Leader, Beth Bye Deputy Majority Leader, Paul Doyle Deputy Majority Leader, Edwin Gomes Deputy Majority Leader, Andrew Maynard Assistant Majority Leader, Dante´ Bartolomeo Assistant Majority Leader, Terry Gerratana Assistant Majority Leader, Gayle Slossberg Assistant Majority Leader, Gary Winfield Majority Whip, Mae Flexer Majority Whip, Ted Kennedy, Jr. Majority Whip, Tim Larson Majority Whip, Marilyn Moore Senate Minority Leader, Leonard Fasano Senate Minority Leader Pro Tempore, Kevin Witkos Deputy Senate Minority Leader Pro Tempore/Minority Caucus Chairman, Rob Kane Chief Deputy Minority Leader, Toni Boucher Chief Deputy Minority Leader, Tony Guglielmo Chief Deputy Minority Leader, John Kissel Deputy Minority Leader, Clark Chapin Deputy Minority Leader, L. Scott Frantz Deputy Minority Leader, Michael McLachlan Assistant Minority Leader, Tony Hwang Assistant Minority Leader, Kevin Kelly Assistant Minority Leader, Art Linares Assistant Minority Leader/Screening Chairman Joe Markley Minority Whip, Paul Formica Minority Whip, Henri Martin LEADERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Speaker of the House, J. -

2011- 2012 Legislative Guide

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Joint Committee on Legislative Management wishes to thank Information Technology employee Robert Caroti for the cover photograph of the State Capitol taken from the Travelers’ tower. Many thanks Bob. LEADERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY SENATE President Pro Tempore, Donald E. Williams, Jr. Majority Leader, Martin M. Looney Chief Deputy President Pro Tempore and Federal Relations Liaison, Joseph J. Crisco Jr. Deputy President Pro Tempore, Eric D. Coleman Deputy President Pro Tempore, Eileen M. Daily Deputy President Pro Tempore, Toni N. Harp Deputy President Pro Tempore, Gary LeBeau Deputy Majority Leader, Edwin A. Gomes Deputy Majority Leader, John W. Fonfara Deputy Majority Leader, Andrew Maynard Deputy Majority Leader, Andrea L. Stillman Assistant President Pro Tempore, Joan Hartley Assistant President Pro Tempore, Edith G. Prague Assistant Majority Leader, Bob Duff Assistant Majority Leader, Edward Meyer Assistant Majority Leader, Gayle Slossberg Majority Whip, Paul Doyle Majority Whip, Anthony Musto Senate Minority Leader, John McKinney Senate Minority Leader Pro Tempore, Leonard Fasano Deputy Senate Minority Leader Pro Tempore/Minority Caucus Chairman Andrew Roraback Chief Deputy Minority Leader, Tony Guglielmo Chief Deputy Minority Leader, John Kissel Deputy Minority Leader, Antonietta “Toni” Boucher Deputy Minority Leader, Robert Kane Deputy Minority Leader, Kevin Witkos Assistant Minority Leader, L. Scott Frantz Assistant Minority Leader, Michael McLachlan Minority Whip, Kevin Kelly Minority Whip, Jason Welch LEADERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Speaker of the House, Christopher G. Donovan Majority Leader, J. Brendan Sharkey Deputy Speaker of the House, Emil “Buddy” Altobello Deputy Speaker of the House, Joe Aresimowicz Deputy Speaker of the House, Robert Godfrey Deputy Speaker of the House, Marie Lopez Kirkley-Bey Deputy Speaker of the House, Linda Orange Deputy Speaker of the House, Kevin Ryan Assistant Deputy Speaker of the House, Louis Esposito Jr. -

The Connecticut General Assembly

The Connecticut General Assembly Joint Committee on Legislative Management Martin M. Looney J. Brendan Sharkey Senate President Pro Tempore Speaker of the House Bob Duff, Senate Majority Leader Joe Aresimowicz, House Majority Leader Leonard Fasano, Senate Minority Leader Themis Klarides, House Republican Leader James P. Tracy Executive Director REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL: 2015 TRANSCRIPTION SERVICES CONTRACT #: JCLM16REG0015 RFP ISSUANCE DATE: June 24, 2015 PROPOSAL DUE DATE: July 24, 2015 TIME: 12:00 pm (noon) Suite 5100 * Legislative Office Building * Hartford, CT 06106-1591 * (860) 240-0100 * fax (860) 240-0122 * [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A CONTRACT INFORMATION ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 A.1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 A.2 Official Agency Contact Information ....................................................................................................................................... 1 A.3 Term of Contract ............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 A.4 Terms and Conditions ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Joint Standing Committee Hearings Appropriations

JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE HEARINGS APPROPRIATIONS PART 21 6993 - 7303 2009 006993 C-/4&7 Post Office Box 1329 To: Appropriations CommMee^, New Haven, CT 06505 Telephone 203 865 1957 From: Sandra KoorejianvJ ^ Facsimile 203 562.9450 Date: 2/23/09 Hotline 203 789 8104 Re: Funding for Legal Services TTY 203 773 0192 endabuse@dvsgnh org htlpV/www dvsgnh org New Haven Legal Assistance Association (LAA) provides support to many victims of domestic violence that they won't receive anywhere else. For over ten years, LAA and Domestic Violence Services of Greater New Haven (DVS) have been in a partnership that has provided civil legal assistance to victims; joint advocacy by attorneys and our advocates; and cross-training to enhance each others' skills. Their work with victims with language barriers and immigrants has been exceptional. Our low income clients desperately need them because there is no one else to provide legal services that keep them and their children safe at home. Our services complement each other. LAA has worked with hundreds of our clients over the years. LAA attorneys not only possess the most up to date knowledge regarding victims' legal rights, they are also sensitive to victims' issues. They are clear about what the courts can and can't do in resolving matters and make good use of community resources. Their prompt availability gives our clients the encouragement they need to deal with the often confusing and intimidating court process. Communication between our offices has been fluid. The following case illustrates how our close collaboration helped a woman become and stay safe. -

Newsletter 5

The Capitol Update SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 CLIENT ALERT: ELECTION 2012 Election season is upon us. On November 6th which will hinge on results in the voters will head to the polls to cast their ballots battleground states of Ohio, Florida, for the Office of President, U.S. Senate, House Virginia, North Carolina, Wisconsin, of Representatives, State Senator and State Iowa, Colorado and New Hampshire. Representative. In the weeks leading up to As of this writing in late September, election day you can expect to be inundated with An update on Connecticut President Obama has 247 electoral State Government mail, television ads and phone calls describing votes in his pocket with Mr. Romney and Politics from The the virtues of one candidate and the failings of Government Affairs Group at 191. Ohio and Florida are “must win” of Murtha Cullina LLP. the opponent. states for Romney. No Republican has Elizabeth M. Gemski Here is a look at races of importance to ever been elected President without Michael J. Martone Connecticut. winning Ohio. It’s also hard to conceive David J. McQuade President of a scenario which has Romney losing Janemarie W. Murphy Florida and winning the election. Should Connecticut remains a solid blue state. The Romney win both Ohio and Florida, he last republican presidential candidate to carry Visit our website at: Connecticut was George Bush Toss Ups Obama/Biden Romney/Ryan www.govtaffairsgroup.com Sr. in 1988. In 2008, then Senator 247 100 191 142 37 68 100 57 58 76 Barack Obama defeated Senator 270 Electoral Votes Needed To Win (Recent Race Changes) John McCain by a whopping WA VT NH 12 Murtha Cullina LLP 3 4 ME MT ND 23 percentage points. -

Home Energy Affordability Gap: 2010 (Connecticut Legislative Districts)

HOME ENERGY AFFORDABILITY GAP: 2010 Connecticut Legislative Districts Prepared for: Operation Fuel Bloomfield, Connecticut Pat Wrice, Executive Director Prepared by: Roger D. Colton Fisher, Sheehan & Colton Public Finance and General Economics Belmont, Massachusetts January 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents………………………………………………………. i Table of Tables…………………………………………………….…… ii The Home Energy Affordability Gap in Connecticut………………….. 1 Home Energy Affordability Gap Reaches into Moderate Income……... 3 Home Energy Burdens…………………………………………………. 5 Federal LIHEAP Coverage……………………………………………... 6 Basic Family Needs Budgets…………………………………………… 7 What Contributes to the Inability to Meet Basic Needs Budget………… 9 Overall Median Income………………………………………………… 10 The Particular Needs of the Working Poor…………………………….. 10 Impact of Energy Prices on Total Shelter Costs……………….. 12 Household Responses to Energy Affordability…………………………. 13 Increasing Funding for Bill Payment Assistance Programs…………….. 15 Funding for LIHEAP………………………………………………….. 15 State Public Benefits Programs……………………………………….. 15 Fuel Fund Funding……………………………………………………. 17 Additional Actions Not Considered…………………………………... 18 Connecticut Home Energy Affordability Gap: 2010 Page i TABLE OF TABLES TABLE Total Home Energy Affordability Gap by Congressional 1 2 District…………………………………………………………… Increase in Home Energy Affordability Gap by Federal Poverty 2 4 Level……………………………………………………………... 3 Poverty Households in Connecticut (2000 Census)……….…….. 5 State Aggregate Home Energy Burdens by Ratio of Income to -

2006 Legislative Guide and Robert Caroti for the Wonderful Photograph of the State Capitol Building

Click on the “Bookmarks” tab to the right for a hot link Table of Contents of the Legislative Guide ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Joint Committee on Legislative Management wishes to thank Information Technology employees Sophie King for editing the 2006 Legislative Guide and Robert Caroti for the wonderful photograph of the State Capitol Building LEADERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY SENATE President Pro Tempore, Donald E. Williams, Jr. Majority Leader, Martin M. Looney Chief Deputy President Pro Tempore and Majority Caucus Chairman, Biagio “Billy” Ciotto Deputy President Pro Tempore, Eric D. Coleman Deputy President Pro Tempore, Eileen M. Daily Deputy President Pro Tempore, Toni N. Harp Deputy President Pro Tempore, Joan Hartley Chief Deputy Majority Leader, Thomas P. Gaffey Deputy Majority Leader, Thomas A. Colapietro Deputy Majority Leader, John W. Fonfara Deputy Majority Leader, Mary Ann Handley Deputy Majority Leader, Andrew J. McDonald Chief Assistant President Pro Tempore and Federal Relations Liaison, Joseph J. Crisco, Jr. Assistant President Pro Tempore, Gary LeBeau Assistant President Pro Tempore, Edith G. Prague Assistant Majority Leader, Donald J. DeFronzo Assistant Majority Leader, Christopher Murphy Majority Whip, Bill Finch Deputy Majority Whip, Bob Duff Deputy Majority Whip, Andrea L. Stillman Assistant Majority Whip, Edward A. Gomes Assistant Majority Whip, Jonathan A. Harris Assistant Majority Whip, Edward Meyer Assistant Majority Whip, Gayle Slossberg Republican Leader, Louis C. DeLuca Minority Leader Pro Tempore, John McKinney Chief Deputy Minority Leader, Catherine Cook Chief Deputy Minority Leader, William H. Nickerson Deputy Minority Leader-At-Large, George L. Gunther Deputy Minority Leader, David Cappiello Deputy Minority Leader, Judith Freedman Deputy Minority Leader, Thomas Herlihy Deputy Minority Leader, John Kissel Assistant Minority Leader, Len Fasano Assistant Minority Leader, Tony Guglielmo Assistant Minority Leader, Andrew Roraback LEADERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Speaker of the House, James A. -

Debating the Statute of Limitations in Child Sexual Abuse Cases; Current Limit of Age 48 Would Be Li…

1/3/13 Debating The Statute of Limitations In Child Sexual Abuse Cases; Current Limit Of Age 48 Would Be Li… HOME | ABOUT | CT POLITICS | EMAIL | RSS FEED BY COURANT STAFF Try FREE Breaking News Mobile Text Alerts: Mobile Phone # SUBSCRIBE More Info ‹‹ Education Committee Hears Test... | Main | Democrats In Canton Thursday N... ›› ABOUT Debating The Statute of Limitations In Child Sexual Abuse Jon Lender, Christopher Keating and Daniela Cases; Current Limit Of Age 48 Would Be Lifted Under Bill Altimari provide insightful and indepth coverage of Connecticut politics... read more By Christopher Keating on March 17, 2010 7:04 PM | Permalink | Comments (2) Email | CT Politics on Courant.com | About Attorneys and advocates called Wednesday for Connecticut to become the fourth state in the nation to eliminate the civil statute of limitations in child sexual abuse cases. The current age of 48 was established by the legislature in 2002 when lawmakers said that a victim should have 30 years to make a claim upon reaching the age of 18. As such, the age of 48 was written into the law. Follow @capitolwatch Sen. Andrew McDonald, a Stamford Democrat who cochairs the judiciary committee, said that many of the witnesses Wednesday were talking about the Roman Catholic Church and Search the allegations of sexual abuse against the late Dr. George Reardon at St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center in Hartford. But he said the bill doesn't mention any particular entity. Archives Select a Month... "This legislation doesn't speak about anybody in particular,'' McDonald said. "It could be family members suing family members.'' ALL OUR BLOGGERS Prompted by the Reardon case, some lawmakers are trying to eliminate the statute of limitations in a similar move to a failed attempt last year that expired in the judiciary committee without a vote. -

TOWN of MANSFIELD TOWN COUNCIL MEETING MONDAY, January 24,2011 COUNCIL CHAMBERS AUDREY P

Note: The Council will hold a reception for Secretary ofState Denise Merrill, State Representative Gregory Haddad and Judge Claire Twerdyat 7:00PM. TOWN OF MANSFIELD TOWN COUNCIL MEETING MONDAY, January 24,2011 COUNCIL CHAMBERS AUDREY P. BECK MUNICIPAL BUILDING 7:30 p.m. AGENDA CALL TO ORDER Page ROLLCALL APPROVAL OF MINUTES 1 OPPORTUNITY FOR PUBLIC TO ADDRESS THE COUNCIL REPORT OF THE TOWN MANAGER REPORTS AND COMMENTS OF COUNCIL MEMBERS OLD BUSINESS 1. Status Report on Assisted/Independent Living Project (Item #2, 10-25-10 Agenda) '" 17 2. Community Water and Wastewater Issues (Item #2,12-13-10 Agenda) 19 NEW BUSINESS 3. Appointment of Council Member 73 4. Meeting with State Legislators 75 5. Appointment to Mansfield Downtown Partnership Board of Directors 87 6. Proposed Open Space Acquisition - Penner Property, White Oak Drive/Jonathan Lane/Fieldstone Drive 89 7. Town Manager's Goals 93 DEPARTMENTAL AND COMMITTEE REPORTS 99 REPORTS OF COUNCIL COMMITTEES PETITIONS, REQUESTS AND COMMUNICATIONS 8. J. Russell re: Town of Mansfield Website's Search Functions 121 9. Storrs Center Phases 1A and 1B Zoning Permit Application 125 10. Legal Notice: Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports 167 11. Governor Dannel P. Malloy Inaugural Message 169 12. Regions as Partners: Recommendations to Governor-Elect Malloy 175 13. MalloylWyman Transition Team: Final Report of the Policy Committee 191 14. Executive Summary: Report to the Connecticut General Assembly From the SustiNet Health Partnership Board of Directors 199 15. Department of Children and Families re: Heart Gallery 201 16. Report of the Task Force to De-Escalate Spring Weekend 203 17. -

Connecticut Federal Candidates U.S

CANDIDATE ENDORSEMENTS 2012 Ratings are as of Sept. 14, 2012 • For any updates go to www.NRAPVF.org a CONNECTICUT FEDERAL CANDIDATES U.S. Senate (R) Linda McMahon AQ (D/WF) Chris Murphy F U.S. House of Representatives DISTRICT 1 DISTRICT 3 DISTRICT 5 (R) John Henry Decker B (R) Wayne Winsley AQ (R) Andrew Roraback C (D) *John Larson F (D) *Rosa DeLauro F (D) Elizabeth Esty DISTRICT 2 DISTRICT 4 (R) Paul Formica ? (R) Steve Obsitnik 7 (D) *Joe Courtney D (D) *Jim Himes F Senate DISTRICT 9 DISTRICT 18 DISTRICT 26 DISTRICT 1 (R) Joe "D" Dinunzio A- (R) Theresa Madonna AQ (R) *Toni Boucher A- (D) Carolanne Curry 7 (R) Barbara Ruhe ? (D) *Paul R. Doyle A (D) *Andrew Maynard A (D) *John W. Fonfara D- DISTRICT 27 DISTRICT 10 DISTRICT 19 (R) Barry Michelson A- DISTRICT 2 (D) *Toni N. Harp D- (R) Christopher Coutu A (D) *Carlo Leone D- (R) Malvi Garcia Lennon ? (D) Catherine A. Osten 7 (D) *Eric D. Coleman D- DISTRICT 11 DISTRICT 28 (D) *Martin M. Looney D- DISTRICT 20 (R) *John McKinney DISTRICT 3 (R) Mike Doyle D- (R) Hector Reveron 7 DISTRICT 12 (D) *Andrea L. Stillman D- DISTRICT 29 (R) Sally White A- (D) *Gary D. LeBeau D- (R) Cindy Cartier AQ (D) * Edward Meyer C DISTRICT 21 (D) *Donald E.Williams D- DISTRICT 4 (R) *Kevin C. Kelly B DISTRICT 30 ? DISTRICT 13 (R) Cheri Ann Pelletier (R) Clark J. Chapin A (R) *Len Suzio A DISTRICT 22 (D) *Steve Cassano B (D) William 0. -

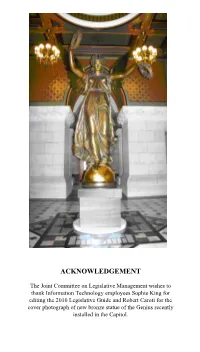

2010 Legislative Guide and Robert Caroti for the Cover Photograph of New Bronze Statue of the Genius Recently Installed in the Capitol

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Joint Committee on Legislative Management wishes to thank Information Technology employees Sophie King for editing the 2010 Legislative Guide and Robert Caroti for the cover photograph of new bronze statue of the Genius recently installed in the Capitol. LEADERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY SENATE President Pro Tempore, Donald E. Williams, Jr. Majority Leader, Martin M. Looney Chief Deputy President Pro Tempore, Thomas P. Gaffey Deputy President Pro Tempore, Eric D. Coleman Deputy President Pro Tempore, Eileen M. Daily Deputy President Pro Tempore, Toni N. Harp Deputy President Pro Tempore, Gary LeBeau Chief Deputy Majority Leader, Mary Ann Handley Deputy Majority Leader, Thomas A. Colapietro Deputy Majority Leader, John W. Fonfara Deputy Majority Leader, Andrew J. McDonald Deputy Majority Leader, Andrea L. Stillman Deputy Caucus Leader and Federal Relations Liaison, Joseph J. Crisco, Jr. Assistant President Pro Tempore, Donald J. DeFronzo Assistant President Pro Tempore, Joan Hartley Assistant President Pro Tempore, Edith G. Prague Chief Assistant Majority Leader, Jonathan A. Harris Assistant Majority Leader, Bob Duff Assistant Majority Leader, Edwin A. Gomes Assistant Majority Leader, Edward Meyer Assistant Majority Leader, Gayle Slossberg Majority Whip, Paul Doyle Majority Whip, Andrew Maynard Assistant Majority Whip, Anthony Musto Senate Minority Leader, John McKinney Senate Minority Leader Pro Tempore, Leonard Fasano Deputy Senate Minority Leader Pro Tempore/Minority Caucus Chairman Andrew Roraback Chief Deputy Minority Leader, Tony Guglielmo Chief Deputy Minority Leader, John Kissel Deputy Minority Leader, Sam Caligiuri Deputy Minority Leader, Dan Debicella Deputy Minority Leader, Robert Kane Assistant Minority Leader, Antonietta “Toni” Boucher Assistant Minority Leader, Kevin Witkos Minority Whip, L.