Oranges Oranges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Ballets Trockedero De Monte Carlo

Le Lac des Cygnes (Swan Lake), Act II Saturday, March 14, 2020, 8pm Sunday, March 15, 2020, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Les Ballet Trockadero de Monte Carlo Featuring Ludmila Beaulemova Maria Clubfoot Nadia Doumiafeyva Helen Highwaters Elvira Khababgallina Irina Kolesterolikova Varvara Laptopova Grunya Protozova Eugenia Repelskii Alla Snizova Olga Supphozova Maya Thickenthighya Minnie van Driver Guzella Verbitskaya Jacques d’Aniels Boris Dumbkopf Nicholas Khachafallenjar Marat Legupski Sergey Legupski Vladimir Legupski Mikhail Mudkin Boris Mudko Mikhail Mypansarov Yuri Smirnov Innokenti Smoktumuchsky Kravlji Snepek William Vanilla Tino Xirau-Lopez Tory Dobrin Artistic Director Isabel Martinez Rivera Associate Director Liz Harler General Manager Cal Performances’ 2019–20 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 21 22 PLAYBILL PROGRAM Le Lac des Cygnes (Swan Lake), Act II Music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Choreography after Lev Ivanovich Ivanov Costumes by Mike Gonzales Décor by Clio Young Lighting by Kip Marsh Benno: Mikhail Mypansarov (friend and confidant to) Prince Siegfried: Vladimir Legupski (who falls in love with) Alla Snizova (Queen of the) Swans Ludmila Beaulemova, Maria Clubfoot, Nadia Doumiafeyva, Minnie van Driver, Elvira Khababgallina, Grunya Protozova, Maya Thickenthighya, Guzella Verbitskaya (all of whom got this way because of) Von Rothbart: Yuri Smirnov (an evil wizard who goes about turning girls into swans) INTERMISSION Pas de Deux or Modern Work to be Announced Le Grand Pas de Quatre Music by Cesare Pugni Choreography after Jules -

Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova

Compiled by Irina Kuzmina Marina Medkova English version Olga Perevezentseva Dmitry Osipenko Digital version Dmitry Osipenko Graphic Design Lilia Garifullina Theatre Union of the Russian Federation Strastnoy Blvd., 10, Moscow, 107031, Russia Tel: +7 (495) 6502846 Fax: +7 (495) 6500132 e-mail: [email protected] www.stdrf.ru Russian Theatre Festivals Guide Compiled by Irina Kuzmina, Marina Medkova. Moscow, Theatre Union of Russia, April 2016 A reference book with information about the structure, locations, addresses and contacts of organisers of theatre festivals of all disciplines in the Russian Federation as of April, 2016. The publication is addressed to theatre professionals, bodies managing culture institutions of all levels, students and lecturers of theatre educational institutions. In Russian and English. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. The publisher is very thankful to all the festival managers who are being in constant contact with Theatre Union of Russia and who continuously provide updated information about their festivals for publication in electronic and printed versions of this Guide. The publisher is particularly grateful for the invaluable collaboration efforts of Sergey Shternin of Theatre Information Technologies Centre, St. Petersburg, Ekaterina Gaeva of S.I.-ART (Theatrical Russia Directory), Moscow, Dmitry Rodionov of Scena (The Stage) Magazine and A.A.Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum. 3 editors' notes We are glad to introduce you to the third edition of the Russian Theatre Festival Guide. -

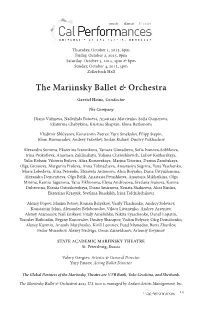

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

Download Booklet

Sergey PROKOFIEV Romeo and Juliet Complete ballet Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop CD 1 75:03 CD 2 69:11 Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953) Romeo and Juliet Act I Act II (contd.) It is a measure of the achievement of Prokofiev’s most ballet’). Rejecting the supposedly empty-headed 1 Introduction 2:39 1 Romeo at Friar Laurence’s 2:50 well-loved stage work that today we take for granted the confections of Marius Petipa (legendary choreographer of 2 Romeo 1:35 2 Juliet at Friar Laurence’s 3:16 concept of a narrative full-length ballet, in which every Tchaikovsky’s ballets), Radlov and his choreographers dance and action advances its story. Indeed, we are now aimed to create ballets with realistic narratives and of 3 The Street Wakens 1:33 3 Public Merrymaking 3:23 so familiar with this masterpiece that it is easy to overlook psychological depth, meanwhile teaching dancers how to 4 4 Morning Dance 2:12 Further Public Festivities 2:32 how audacious was the concept of translating so verbal a convey the thoughts and motivations of the characters 5 The Quarrel 1:43 5 Meeting of Tybalt and Mercutio 1:56 drama as Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into a full- they portrayed. As artistic director of the Leningrad State 6 The Fight 3:43 6 The Duel 1:27 length ballet. Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet (formerly the 7 The Duke’s Command 1:21 7 Death of Mercutio 2:31 We largely owe its existence to Sergey Radlov, a Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, but now widely known by the 8 Interlude 1:54 8 Romero Decides to Avenge Mercutio 2:07 disciple of the revolutionary theatre director Vsevolod abbreviation Akopera), Radlov directed two early 9 At the Capulets’ 9 Finale 2:07 Meyerhold. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

St. Petersburg Is Recognized As One of the Most Beautiful Cities in the World. This City of a Unique Fate Attracts Lots of Touri

I love you, Peter’s great creation, St. Petersburg is recognized as one of the most I love your view of stern and grace, beautiful cities in the world. This city of a unique fate The Neva wave’s regal procession, The grayish granite – her bank’s dress, attracts lots of tourists every year. Founded in 1703 The airy iron-casting fences, by Peter the Great, St. Petersburg is today the cultural The gentle transparent twilight, capital of Russia and the second largest metropolis The moonless gleam of your of Russia. The architectural look of the city was nights restless, When I so easy read and write created while Petersburg was the capital of the Without a lamp in my room lone, Russian Empire. The greatest architects of their time And seen is each huge buildings’ stone worked at creating palaces and parks, cathedrals and Of the left streets, and is so bright The Admiralty spire’s flight… squares: Domenico Trezzini, Jean-Baptiste Le Blond, Georg Mattarnovi among many others. A. S. Pushkin, First named Saint Petersburg in honor of the a fragment from the poem Apostle Peter, the city on the Neva changed its name “The Bronze Horseman” three times in the XX century. During World War I, the city was renamed Petrograd, and after the death of the leader of the world revolution in 1924, Petrograd became Leningrad. The first mayor, Anatoly Sobchak, returned the city its historical name in 1991. It has been said that it is impossible to get acquainted with all the beauties of St. -

The History of Russian Ballet

Pet’ko Ludmyla, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Dragomanov National Pedagogical University Savina Kateryna Dragomanov National Pedagogical University Institute of Arts, student THE HISTORY OF RUSSIAN BALLET Петько Людмила к.пед.н., доцент НПУ имени М.П.Драгоманова (Украина, г.Киев) Савина Екатерина Национальный педагогический университет имени М.П.Драгоманова (Украина, г.Киев), Інститут искусствб студентка Annotation This article is devoted to describing of history of Russian ballet. The aim of the article is to provide the reader some materials on developing of ballet in Russia, its influence on the development of ballet schools in the world and its leading role in the world ballet art. The authors characterize the main periods of history of Russian ballet and its famous representatives. Key words: Russian ballet, choreographers, dancers, classical ballet, ballet techniques. 1. Introduction. Russian ballet is a form of ballet characteristic of or originating from Russia. In the early 19th century, the theatres were opened up to anyone who could afford a ticket. There was a seating section called a rayok, or «paradise gallery», which consisted of simple wooden benches. This allowed non- wealthy people access to the ballet, because tickets in this section were inexpensive. It is considered one of the most rigorous dance schools and it came to Russia from France. The specific cultural traits of this country allowed to this technique to evolve very fast reach his most perfect state of beauty and performing [4; 22]. II. The aim of work is to investigate theoretical material and to study ballet works on this theme. To achieve the aim we have defined such tasks: 1. -

Kirov Ballet & Orchestra of the Mariinsky Theatre

Cal Performances Presents Tuesday, October 14–Sunday, October 19, 2008 Zellerbach Hall Kirov Ballet & Orchestra of the Mariinsky Theatre (St. Petersburg, Russia) Valery Gergiev, Artistic & General Director The Company Diana Vishneva, Irma Nioradze, Viktoria Tereshkina Alina Somova, Yulia Kasenkova, Tatiana Tkachenko Andrian Fadeev, Leonid Sarafanov, Yevgeny Ivanchenko, Anton Korsakov Elena Bazhenova, Olga Akmatova, Daria Vasnetsova, Evgenia Berdichevskaya, Vera Garbuz, Tatiana Gorunova, Grigorieva Daria, Natalia Dzevulskaya, Nadezhda Demakova, Evgenia Emelianova, Darina Zarubskaya, Lidia Karpukhina, Anastassia Kiru, Maria Lebedeva, Valeria Martynyuk, Mariana Pavlova, Daria Pavlova, Irina Prokofieva, Oksana Skoryk, Yulia Smirnova, Diana Smirnova, Yana Selina, Alisa Sokolova, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Lira Khuslamova, Elena Chmil, Maria Chugay, Elizaveta Cheprasova, Maria Shirinkina, Elena Yushkovskaya Vladimir Ponomarev, Mikhail Berdichevsky, Stanislav Burov, Andrey Ermakov, Boris Zhurilov, Konstantin Zverev, Karen Ioanessian, Alexander Klimov, Sergey Kononenko, Valery Konkov, Soslan Kulaev, Maxim Lynda, Anatoly Marchenko, Nikolay Naumov, Alexander Neff, Sergey Popov, Dmitry Pykhachev, Sergey Salikov, Egor Safin, Andrey Solovyov, Philip Stepin, Denis Firsov, Maxim Khrebtov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vasily Sherbakov, Alexey Timofeev, Kamil Yangurazov Kirov Ballet of the Mariinsky Theatre U.S. Management: Ardani Artists Management, Inc. Sergei Danilian, President & CEO Made possible, in part, by The Bernard Osher Foundation, in honor of Robert -

Ballet, Culture and Elite in the Soviet Union on Agrippina Vaganova’S Ideas, Teaching Methods, and Legacy

Ballet, culture and elite in the Soviet Union On Agrippina Vaganova’s Ideas, Teaching Methods, and Legacy Magdalena L. Midtgaard Magdalena Midtgaard VT 2016 Examensarbete, 15 hp Master program, Idéhistoria 120 hp Balett, kultur och elit i Sovjetunionen Om Agrippina Vaganovas idéer, undervisningsmetoder och arv Magdalena Midtgaard vt. 2016 Abstract. Balettutbildning har varit auktoritär och elitistisk i århundraden. Med utgångspunkt i Agrippina Vaganova och hennes metodiska systematisering av balettundervisning diskuteras frågor om elit, lärande och tradition inom balettundervisning. Vaganova var en länk mellan tsartidens Ryssland och det nya Sovjet och bidrog aktivt till att balett som konstform, trots sin aristokratiska bakgrund, fördes vidare och blev en viktig kulturpolitiskt aktivitet i Sovjet. Med underlag i texter av Bourdieu och Said diskuteras elit, kulturellt kapital och elitutbildning för att förklara några av de politiska och samhällsmässiga mekanismer som bidragit till balettens unika position i Sovjet. För att placera Vaganova som pedagog i förhållande till balettundervisning och balett genom tiden, presenteras korta informativa kapitel om baletthistoria, och utveckling och spridning av Vaganovas metod, både i Sovjet/Ryssland och i andra länder. Key words: Classical ballet, Vaganova, ballet education, elite education, cultural politics in the Soviet Union My sincere thanks to Sharon Clark Chang for proof reading and correcting my English, and to Louise Midtgaard and Sofia Linnea Berglund for valuable thoughts on Vaganova and ballet pedagogy and education in general. 2 Contents 1. Introduction p. 5 1.1 Sources and method p. 6 1.2 Theoretical perspectives on elite culture p. 7 2. Background p. 8 2.1 A short history of ballet p. -

Worldballetday 2021 Join the World's Top Ballet Companies for Biggest

Press Release 1 September 2021 #WorldBalletDay 2021 Join the world’s top ballet companies for biggest-ever global celebration of dance • Free digital live stream on 19 October • #WorldBalletDay collaborates with TikTok for the first time • Watch via www.worldballetday.com Today, The Royal Ballet, Bolshoi Ballet and The Australian Ballet are delighted to announce that #WorldBalletDay 2021 will take place on 19 October. The global celebration returns for its eighth year, bringing together a host of the world’s leading companies for a packed day of dance. Over the course of the day, rehearsals, discussions and classes will be streamed for free across 6 continents, offering unique behind-the-scenes glimpses of ballet’s biggest stars and upcoming performers. With COVID-19 guidelines changing daily across the globe, dance companies have struggled to return to stages and rehearsal studios. This year's celebration will recognise the extraordinary resilience of this art form in the face of those challenges, showcasing the breadth of talent performing, choreographing, and working on productions today. The 2021 edition of #WorldBalletDay is set to be the biggest ever. In collaboration with TikTok, and with streams across YouTube and Facebook, this year’s viewership is expected to exceed the previous record set in 2019, when #WorldBalletDay content was viewed over 300 million times. Kevin O’Hare, Director of The Royal Ballet, comments: ‘This year’s celebration of our cherished art form will be more important and meaningful than ever, as friends and colleagues around the world return to the stage and the studio, many still with great difficulty. -

Dead Souls and Gogol's Readers: Collective Creation And

New Zealand Slavonic Journal, vol. 41 (2007) Benjamin Sutcliffe (Miami University, USA) WRITING THE URALS: PERMANENCE AND EPHEMERALITY IN OL'GA SLAVNIKOVA’S 2017 Ol'ga Slavnikova’s novel 2017 (Vagrius, 2006) made her the second woman to win Russia’s coveted Booker Prize, garnering conflicting critical responses in the process.1 Many hurried to label the narrative a dystopia: 2017’s last hundred pages depict the centenary of the November ‘revolu- tion’, chronicling how crowds commemorate the event by dressing up as Reds or Whites and slaughtering their enemies (Chantsev 287; Eliseeva 14). Other critics, and Slavnikova herself, see dystopia as only one strand in the work (Slavnikova ‘Mne ne terpitsia’, 18; Basinskii 13). As Elena Elagina observes, this is a work whose different layers appeal to varying readers, yet ultimately the narrative is less stratified than interwoven as it portrays the life of one Veniamin Iur'evich Krylov, a gem poacher (khitnik) and skilled carver of valuable stones (Elagina 217). Krylov, who lives in Ekaterinburg, discovers that his new love, the enigmatic yet nondescript Tania, is none other than the Stone Maiden of local legend—a being who shows some men the location of buried gems and lures others to destruc- tion. According to the idiosyncratic rules of their relationship, they meet at randomly chosen locations, knowing neither the other’s address, nor phone number, nor real name—a scenario that results in Krylov losing contact with Tania after a terrorist attack disrupts their planned rendezvous (Slav- nikova 2017, 324, 255-56, 84-86, 31). When he finds her, Krylov discov- ers that Tania is now less a human than a stylised image. -

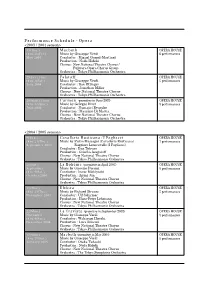

Performance Schedule

Performance Schedule - Opera <2003 / 2004 season> 13(Thu.) Macbeth OPERA HOUSE thru 28(Fri.) Music by Giuseppe Verdi 6 performances May 2004 Conductor : Miguel Gomez-Martinez Production : Noda Hideki Chorus : New National Theatre Chorus / Fujiwara Opera Chorus Group Orchestra : Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra 25(Fri.) June Falstaff OPERA HOUSE thru 3(Sat.) Music by Giuseppe Verdi 5 performances July 2004 Conductor : Dan Ettinger Production : Jonathan Miller Chorus : New National Theatre Chorus Orchestra : Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra 28(Mon.) June Carmen (première in June 2002) OPERA HOUSE thru 11(Sun.) Music by Georges Bizet 5 performances July 2004 Conductor : Numajiri Ryusuke Production : Maurizio Di Mattia Chorus : New National Theatre Chorus Orchestra : Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra <2004 / 2005 season> 9(Thu.) Cavalleria Rusticana / I Pagliacci OPERA HOUSE thru 23(Thu.) Music by Pietro Mascagni (Cavalleria Rusticana) 7 performances September 2004 Ruggiero Leoncavallo (I Pagliacci) Conductor : Ban Tetsuro Production : Grischa Asagaroff Chorus : New National Theatre Chorus Orchestra : Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra 25(Sat.) La Bohème (première in April 2003) OPERA HOUSE September Music by Giacomo Puccini 5 performances thru 9(Sat.) Conductor : Inoue Michiyoshi October 2004 Production : Aguni Jun Chorus : New National Theatre Chorus Orchestra : Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra 11(Thu.) Elektra OPERA HOUSE thru 23(Tue.) Music by Richard Strauss 5 performances November 2004 Conductor : Ulf Schirmer Production : Hans-Peter Lehmann Chorus : New National