Peter E. Gordon Professor of History Harvard University Introduction Harvard University Now Boasts of a Great Number of Accompli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Surface and Postmodern Simulation a Retrospective Retrieval

introduction Modern Surface and Postmodern Simulation A Retrospective Retrieval Denn was innen, das ist außen! Johann Wolfgang von Goethe agendas of surface and simulacrum It is in our time that the Enlightenment project has reached its ultimate implosion. In visual terms, the twentieth century of the western hemi- sphere will be remembered as the century in which content yielded to form, text to image, depth to façade, and Sein to Schein. For over a hundred years, mass cultural phenomena have been growing in importance, taking over from elite structures of cultural expression to become sites where real power resides, and dominating ever more surely our social imaginary. As reflections of the processes of capitalist industrialization in forms clad for popular consumption, these manifestations are literal and conceptual expressions of surface:1 they promote external appearance to us in such arenas as architecture, advertising, film, and fashion. Located as we are at the outset of the new millennium, some may recognize with trepidation that mass culture is becoming so wedded to highly orchestrated and intru- sive electronic formats that there seems to be less and less opportunity for any creative maieutics, or participatory “wiggle room.” Modernity’s sur- faces, entirely site-and-street-specific yet mobile and mobilizing, have been replaced by the stasis of the fluid mobility granted to our perception by the technologies of television, the VCR, the World Wide Web, and vir- tual reality.2 Perhaps as a result of this underlying discomfort, we appear to have a case of what Fredric Jameson has called “inverted millenarianism”:3 rather than look forward at future developments, we choose, almost apotropai- 1 2 / Introduction cally, to look back at how mass culture emerged in the first place. -

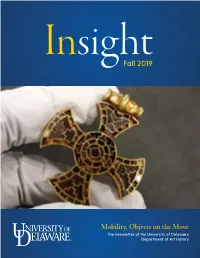

Fall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move

InsightFall 2019 Mobility, Objects on the Move The newsletter of the University of Delaware Department of Art History Credits Fall 2019 Editor: Kelsey Underwood Design: Kelsey Underwood Visual Resources: Derek Churchill Business Administrator: Linda Magner Insight is produced by the Department of Art History as a service to alumni and friends of the department. Contact Us Sandy Isenstadt, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History Contents E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8105 Derek Churchill, Director, Visual Resources Center E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 From the Chair 4 Commencement 28 Kelsey Underwood, Communications Coordinator From the Editor 5 Graduate Student News 29 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-1460 Around the Department 6 Graduate Student Awards Linda J. Magner, Business Administrator E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8416 Faculty News 11 Graduate Student Notes Lauri Perkins, Administrative Assistant Faculty Notes Alumni Notes 43 E: [email protected] P: 302-831-8415 Undergraduate Student News 23 Donors & Friends 50 Please contact us to pose questions or to provide news that may be posted on the department Undergraduate Student Awards How to Donate website, department social media accounts and/ or used in a future issue of Insight. Undergraduate Student Notes Sign up to receive the Department of Art History monthly newsletter via email at ow.ly/ The University of Delaware is an equal opportunity/affirmative action Top image: Old College Hall. (Photo by Kelsey Underwood) TPvg50w3aql. employer and Title IX institution. For the university’s complete non- discrimination statement, please visit www.udel.edu/home/legal- Right image: William Hogarth, “Scholars at a Lecture” (detail), 1736. -

TRACIE M. MATYSIK Department of History

TRACIE M. MATYSIK Department of History . University of Texas at Austin 1 University Station, B7000 Austin, TX 78704 ACADEMIC POSITIONS • 2009-present: Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin Core Faculty Member, Center for European Studies Core Faculty Member, Comparative Literature Core Faculty Member, Schustermann Center for Jewish Studies Core Faculty Member, Center for Women’s and Gender Studies • 2002-2009: Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin • 2016-present: Co-editor, Modern Intellectual History • 2015-2018: Associate Director, Center for European Studies, University of Texas at Austin • 2007, 2010: Guest Faculty, Viadrina Universität, Frankfurt an der Oder, Germany • 2002-2003: James Bryant Conant Fellow, Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University • 2001-2002: Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of German Studies, Cornell University EDUCATION Ph.D., August 2001 Department of History, Cornell University M.A., August 1997 Department of History, Cornell University B.A., June 1994 Program in the Comparative History of Ideas, University of Washington, Seattle RECENT SIGNIFICANT PUBLICATIONS Books Reforming the Moral Subject: Ethics and Sexuality in Central Europe, 1890-1930 (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2008). German Modernities from Wilhelm to Weimar: A Contest of Futures, co-edited with Geoff Eley and Jennifer L. Jenkins (London: Bloomsbury, 2016). When Spinoza Met Marx: Experiments in Non-Humanist Activity, manuscript in progress, under contract with University of Chicago Press. Articles “Revolutionary Messianisms, Spinozist Variations: German-Jewish Responses to Hegelian Dialectics,” in Spinoza and Modern Jewish Philosophy, ed. Michael Rosenthal (New York, Palgrave, forthcoming 2019) (9,367 words). “Writing the History of Spinozism,” History and Theory 55:3 (2016): 401-417. -

Martin Jay – Habermas and Postmodernism

218 / JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND AESTHETICS HABERMAS AND POSTMODERNISM / 219 Whether or not his more recent works signification of detour, temporalizing delay; will dispel this caricature remains to be seen. ‘deferring.”4 Differentiation, in other words, FROM THE ARCHIVES From all reports of the mixed reception he implies for Derrida either nostalgia for a lost received in Paris when he gave the lectures unity or conversely a utopian hope for a that became Die philosophische Diskurs der future one. Additionally, the concept is Moderne, the odds are not very high that a suspect for deconstruction because it implies more nuanced comprehension of his work the crystallization of hard and fast will prevail, at least among certain critics. distinctions between spheres, and thus fails Habermas and Postmodernism At a time when virtually any defence of to register the supplementary rationalism is turned into a brief for the interpenetrability of all subsystems, the automatic suppression of otherness, effaced trace of alterity in their apparent heterogeneity and non-identity, it is hard to homogeneity, and the subversive absence predict a widely sympathetic hearing for his undermining their alleged fullness or complicated argument. Still, if such an presence. outcome is to be made at all possible, the Now, although deconstruction ought not Martin Jay task of unpacking his critique of to be uncritically equated with postmodernism and nuanced defence of postmodernism, a term Derrida himself has modernity must be forcefully pursued. One never embraced, one can easily observe that n the burgeoning debate over the out-dated liberal, enlightenment way to start this process is to focus on a the postmodernist temper finds différance apparent arrival of the postmodern rationalism. -

Department of History

———— UC BERKELEY ———— DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY winter 2016 newsletter 1 CONTENTS Chair's Letter, 4 Department News, 6 Faculty Updates, 8 In Memoriam, 13 Faculty Book Reviews, 14 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY University of California, Berkeley 3229 Dwinelle Hall, MC 2550 Berkeley, CA 94720-2550 Phone: 510-642-1971 Fax: 510-643-5323 Email: [email protected] Web: history.berkeley.edu Like Berkeley History on Facebook! Facebook.com/UCBerkeleyHistory Cover images courtesy of UC Berkeley Public Affairs Photo by Daniel Parks SUPPORT THE FUTURE OF HISTORY Donor support plays a critical role in the ways we are able to sustain and enhance the teaching and research mission of the department. Friends of Cal funds are utilized throughout the year in the following ways: • Travel grants for undergraduates researching the material for their senior thesis project • Summer grants (for travel or language study) for graduate students • Dissertation write-up grants for PhD candidates • Conference travel for graduate students who are presenting papers or participating in job interviews • Prizes for the best dissertation and undergraduate thesis • Equipment for the graduate computer lab • Workstudy positions that provide instructional support • Graduate space coordinator position Most importantly, Friends of Cal funds allow the department to direct funding to students in any field of study, so that the money can be directed where it is most needed. This unrestricted funding has enabled us to enhance our multi-year funding package so that we can continue to focus on maintaining the quality that is defined by a Berkeley degree. To support the Department of History, please donate online at give.berkeley.edu or mail checks payable to UC Berkeley Foundation to the address listed on the previous page. -

Theodor W. Adorno - Essays on Music

Theodor W. Adorno - Essays on Music Selected, with Introduction, Commentary, and Notes by Richard Leppert. Translations by Susan H. Gillespie and others Contents Preface and Acknowledgments Translator's Note Abbreviations Introduction by Richard Leppert 1. LOCATING MUSIC: SOCIETY, MODERNITY, AND THE NEW Commentary by Richard Leppert Music, Language, and Composition (1956) Why Is the New Art So Hard to Understand? (1931) On the Contemporary Relationship of Philosophy and Music (1953) On the Problem of Musical Analysis The Aging of the New Music (1955) The Dialectical Composer (1934) 2. CULTURE, TECHNOLOGY, AND LISTENING Commentary by Richard Leppert The Radio Symphony (1941) The Curves of the Neddle (1927/1965) The Form of the Phonograph Record Opera and the Long-Playing Record (1969) On the Fetish-Character in Music and the Regression of Listening (1938) Little Heresy (1965) 3. MUSIC AND MASS CULTURE Commentary by Richard Leppert What National Socialism Has Done to the Arts (1945) On the Social Situation of Music (1932) On Popular Music [With the assistance of George Simpson] (1941) On Jazz (1936) Farewell to Jazz (1933) Kitsch (c. 1932) Music in the Background (c. 1934) 4. COMPOSITION, COMPOSERS, AND WORKS Commentary by Richard Leppert Late Style in Beethoven (1937) Alienated Masterpiece: The Missa Solemnis (1959) Wagner's Relevance for Today (1963) Mahler Today (1930) Marginalia on Mahler (1936) The Opera Wozzeck (1929) Toward an Understanding of Schoenberg (1955/1967) Difficulties (1964, 1966) Bibliography Introduction Richard Leppert Life and Works Adorno was a genius; I say that without reservation. [He] had a presence of mind, a spontaneity of thought, a power of formulation that I have never seen before or since. -

Response to Critics Adorno and Existence

Abstract Peter Gordon’s response to Espen Hammer, Gordon Finlayson, and Iain Macdonald. Volume 2, Issue 1, September 2018 Keywords Response to Critics Theodor W. Adorno; Peter E. Gordon, existentialism, Adorno and Existence; philosophy Adorno and Existence Peter E. Gordon Harvard University [email protected] 71 | Gordon Response FOR any author it is a true gift to receive genuinely Adorno’s criticisms of Husserl and then Heidegger, with special discerning and critical remarks that open up one’s work in attention Adorno’s controversial claim that both philosophers unexpected ways to reveal themes and problems the author remained in some fashion, either overtly or covertly, confined may have never anticipated. I am deeply grateful to Espen to a kind of philosophical idealism. 3) In the third and final Hammer, Iain Macdonald, and Gordon Finlayson for their portion of this paper, I respond to concerns raised chiefly by commentaries on my book, Adorno and Existence. They have Macdonald, though also by Hammer, regarding the status of stated their views with remarkable generosity, though the religion in my interpretation, namely, the question as to challenges they have presented are considerable. My only whether I am “theologizing” Adorno, and whether we should regret is that I could not benefit from this criticism before instead adopt a more materialist perspective on Adorno’s publishing the book (though I should note that Espen Hammer readings, especially though not exclusively his readings of did offer a great many discerning comments on the Kierkegaard and Kafka’s “Odradek.” manuscript, and the book is far better than it might have been thanks to his insights along with those of the other readers Immanent Critique or Meta-Critique? whose names appear in the acknowledgements). -

The Concept of Critique in Critical Theory

Outhwaite W. Generations of Critical Theory? Berlin Journal of Critical Theory 2017, 1(1), 5-27. Copyright: ©2017. With permission granted from the publisher, this is the accepted manuscript of an article published by Berlin Journal of Critical Theory. weblink to article: http://www.bjct.de/home.html Date deposited: 25/08/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Generations of Critical Theory? This journal is oriented to re-evaluating early critical theory and is therefore an appropriate place to pose some questions about the periodisation of critical theory as a whole. Whether or not one accepts a generational model with Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse et al in the first generation, Habermas, Apel and Wellmer in the second and Honneth, Fraser and a cluster of other German and North American theorists in the third, a model powerfully criticised in relation to Habermas by Stefan Müller-Doohm (2017), there is general agreement that Habermas’s project has always been substantially diferent from that of the earlier critical theorists – themselves of course quite differentiated despite Horkheimer’s somewhat managerial attempts to present them as a team. But whereas Horkheimer’s earlier opposition to Habermas was based on anxiety that he was too radical and outspoken (Müller-Doohm 2016: 80-88), later commentators have polarised roughly between those who see Habermas’s project as a continuation of critical theory in a different mode more adapted to the realities of postwar advanced capitalist societies with their apparently stable liberal polities and those who see it as an abandonment of some of the more radical motifs of earlier critical theory. -

The Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia

Praxis Philosophy’s ’Older Sister‘ The Reception of Critical Theory in the Former Yugoslavia Marjan Ivković* Without any doubt, the former Yugoslavia was among the more fertile soils globally for the reception and flourishing of the tradition of Critical Theory over a span of several decades. Practically all major works by both the ‘first’- and ‘second-generation’ critical theorists were translated into Serbo-Croatian in the 1970s and 1980s. Not only were there translations of the most influential studies of Critical Theory’s history and theoretical legacy of that time (Martin Jay, Alfred Schmidt and Gian-Enrico Rusconi), there were also studies by local authors such as Simo Elaković’s Filozofija kao kritika društva (Philosophy as Critique of Society) and Žarko Puhovski’s Um i društvenost (Reason and Sociality). Contemporary Serbian political scientist Đorđe Pavićević remarks about Critical Theory in Yugoslavia that “this group of authors can perhaps be considered the most thoroughly covered area of scholarhip within political theory and philosophy in terms of both translations and original works up to the early 1990s” (2011: 51). Yet, throughout socialist times, the broad and differentiated reception of Critical Theory never really crossed the threshold of a truly original appropriation, whether it be attempts to elaborate existing perspectives in Critical Theory, modify them in light of particular socio-historical circumstances of the local context, or apply them as a research framework for the empirical study of society. The peculiarity -

Pgordon CV Sept 2020

PETER E. GORDON Amabel B. James Professor of History Faculty Affiliate, Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures Faculty Affiliate, Department of Philosophy The Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University 27 Kirkland Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138 [email protected] CURRENT ACADEMIC TITLES Amabel B. James Professor of History, Harvard University: appointed 2011 Walter Channing Cabot Fellow: Excellence in Scholarship, 2017-2018 Faculty Affiliate, Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures Faculty Affiliate, Department of Philosophy Resident Faculty, The Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies Steering Committee, The Committee on Degrees in Social Studies Co-Editor, UPenn Series in Intellectual History of the Modern Age (ongoing) Steering Committee, The School of Criticism and Theory (Cornell University) BOOKS & BOOK AWARDS Continental Divide: Heidegger, Cassirer, Davos. Harvard University Press, 2010 (hardcover); 2012 (paper) • The Jacques Barzun Prize, awarded by the American Philosophical Society, 2010 • Japanese translation forthcoming Rosenzweig and Heidegger: Between Judaism and German Philosophy (The University of California Press, 2003, hardcover; 2005, paperback) • Morris D. Forkosch Prize, Best Book in Intellectual History, 2003 by The Journal of the History of Ideas • Salo W. Baron Prize, Best Book in Jewish Studies, 2003 by The American Academy for Jewish Research • Goldstein-Goren Prize, Best Book in Jewish Thought in Three Years, 2004 by Ben-Gurion University, Israel • Koret Foundation Publication Prize, 2002 The Cambridge Companion to Modern Jewish Philosophy. Co-Editor, with Michael Morgan. (Cambridge University Press, 2007) The Modernist Imagination: Intellectual History and Critical Theory. Essays in Honor of Martin Jay. Co-Editor, with Breckman, et al. (Berghahn Books, 2008) Weimar Thought: A Contested Legacy. -

Heidegger and Cassirer on Science After the Cassirer and Heidegger of Davos

History of European Ideas ISSN: 0191-6599 (Print) 1873-541X (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rhei20 Heidegger and Cassirer on Science after the Cassirer and Heidegger of Davos Hans-Jörg Rheinberger To cite this article: Hans-Jörg Rheinberger (2015) Heidegger and Cassirer on Science after the Cassirer and Heidegger of Davos, History of European Ideas, 41:4, 440-446, DOI: 10.1080/01916599.2014.981020 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2014.981020 © 2015 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 27 Nov 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 420 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rhei20 History of European Ideas, 2015 Vol. 41, No. 4, 440–446, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01916599.2014.981020 Heidegger and Cassirer on Science after the Cassirer and Heidegger of Davos HANS-JÖRG RHEINBERGER* Director Emeritus, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin, Germany Summary The paper exposes the views of Ernst Cassirer and Martin Heidegger on the dynamics of the sciences of their day, as both developed them in the two decades after the encounter of the two philosophers in Davos in 1928. It emphasizes points of common concern, and it compares their positions to those of contemporary philosophers of science Gaston Bachelard and Edgar Wind. Keywords: Heidegger; Age of the World Picture; Cassirer; Logic of the Humanities; Gaston Bachelard; Edgar Wind; historical epistemology Content 1. -

What Is Intellectual History? a Frankly Partisan Introduction to a Frequently Misunderstood Field

What is Intellectual History? A Frankly Partisan Introduction to a Frequently Misunderstood Field Peter E. Gordon Amabel B. James Professor of History & Harvard College Professor Harvard University Revised Summer, 2013 Please do not cite or circulate without author’s permission Introduction Harvard University now boasts of a great number of accomplished historians whose interests and methods align them primarily—though not necessarily exclusively—with intellectual history. These include (in alphabetical order): David Armitage, Ann Blair, Peter Bol, Joyce Chaplin, Peter Gordon, James Hankins, Andrew Jewett, James Kloppenberg, Samuel Moyn, and Emma Rothschild. But just what is intellectual history? Intellectual history is an unusual discipline, eclectic in both method and subject matter and therefore resistant to any single, globalized definition. Practitioners of intellectual history tend to be acutely aware of their own methodological commitments; indeed, a concern with historical method is characteristic of the discipline. Because intellectual historians are likely to disagree about the most fundamental premises of what they do, any one definition of intellectual history is bound to provoke controversy. In this essay, I will offer a few introductory remarks about intellectual history, its origins and current directions. I have tried to be fair in describing the diversity of the field, but where judgment has seemed appropriate I have not held back from offering my own opinions. The essay is frankly partisan, in that it reflects my own preferences and my own conception of where intellectual history stands in relation to other methodologies. I hope, however, that it can serve as an introductory summary and guide, one will be of some use for students at both the undergraduate and graduate level who are considering work in intellectual history.