Brought to You by Provided by Firenze University Press: E-Journals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents (Pdf)

Contents Poetry Ireland Review 123 Eavan Boland 5 editorial Nan Cohen 7 a liking for clocks Eamon McGuinness 8 a gift Afric McGlinchey 9 in an instant of refraction and shadow Mara Bergman 10 the night we were dylan thomas Joseph Horgan 11 art history of emigration Maria Johnston 12 review: michael longley, john montague Harry Clifton 17 thérèse and the jug Simon West 18 on a trip to van diemen’s land Maresa Sheehan 20 our last day Niamh Boyce 21 hans ardently collects patients’ art work Alan Titley 22 maolra seoighe Proinsias Ó Drisceoil 23 review: biddy jenkinson, aifric mac aodha John D Kelly 27 the red glove Eva Bourke 28 small railway stations Catherine Phil MacCarthy 29 legacies of empire Richard W Halperin 30 the beach, malahide Matt Kirkham 31 kurt responds to adele’s call to remove a spider from the bathtub Susan Lindsay 32 when they’ve grown another me Jaki McCarrick 34 review: pete mullineaux, noel duffy, patrick moran Stav Poleg 39 listen, you have to read in a foreign language Noel Monahan 40 two women at a window Stephen Spratt 41 subjectivity AB Jackson 42 the mermayd Cathi Weldon 43 in the key of alzheimer’s John F Deane 44 old bones June Wentland 46 ‘their whiteness bears no relation to laundry ...’ Louis Mulcahy 47 potadóireacht na caolóige Harry Clifton 48 review: michael o’loughlin Matt Bryden 52 the lookout Orla Martin 53 the poets Catullus 54 ‘if you’re lucky you’ll dine well’ John Sewell 55 being alive Tess Adams 56 i hate my stinking therapist Patrick Holloway 57 barrage Eleanor Rees 58 st. -

Fleming-The-Book-Of-Armagh.Pdf

THE BOOK OF ARMAGH BY THE REV. CANON W.E.C. FLEMING, M.A. SOMETIME INCUMBENT OF TARTARAGHAN AND DIAMOND AND CHANCELLOR OF ARMAGH CATHEDRAL 2013 The eighth and ninth centuries A.D. were an unsettled period in Irish history, the situation being exacerbated by the arrival of the Vikings1 on these shores in 795, only to return again in increasing numbers to plunder and wreak havoc upon many of the church settlements, carrying off and destroying their treasured possessions. Prior to these incursions the country had been subject to a long series of disputes and battles, involving local kings and chieftains, as a result of which they were weakened and unable to present a united front against the foreigners. According to The Annals of the Four Masters2, under the year 800 we find, “Ard-Macha was plundered thrice in one month by the foreigners, and it had never been plundered by strangers before.” Further raids took place on at least seven occasions, and in 941 they record, “Ard-Macha was plundered by the same foreigners ...” It is, therefore, rather surprising that in spite of so much disruption in various parts of the country, there remained for many people a degree of normality and resilience in daily life, which enabled 1 The Vikings, also referred to as Norsemen or Danes, were Scandinavian seafarers who travelled overseas in their distinctive longships, earning for themselves the reputation of being fierce warriors. In Ireland their main targets were the rich monasteries, to which they returned and plundered again and again, carrying off church treasures and other items of value. -

Spectral Clustering on Mercury Hollows: the Dominici Crater Case

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) 1329.pdf SPECTRAL CLUSTERING ON MERCURY HOLLOWS: THE DOMINICI CRATER CASE. A. Lucchetti1, M. Pajola2,3,1, G. Cremonese1, C. Carli4, G. A. Marzo5 and T. Roush3, 1INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, 35131 Padova, Italy ([email protected] ), 2Universities Space Research Association, NASA NPP Program (Supported by an appointment at NASA Ames Research Center: [email protected]), 3NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA; 4INAF-IAPS Roma, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali di Roma, Via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 00133 Rome, Italy; 5ENEA Centro Ricerche Casaccia, 00123 Rome, Italy. Introduction: The Mercury Dual Imaging System [8], i.e. incidence angle of 30°, emission angle of 0° (MDIS, [1]) onboard NASA MESSENGER (MErcury and phase angle of 30°. On the photometrically cor- Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and rected dataset we applied a statistical clustering over Ranging) spacecraft, provided the first global coverage the entire dataset based on a K-means partitioning al- of Mercury's surface with varying spatial resolution. gorithm [9]. It was developed and evaluated by [9-11] Early in the mission, high-resolution images showed and makes use of the Calinski and Harabasz criterion that specific areas exhibiting high reflectance and rela- [12] to find the intrinsically natural number of clusters, tive bluer in color were composed of shallow, irregular making the process unsupervised. A natural number of and rimless, flat-floored depressions with bright interi- ten clusters was identified within the crater and its ors and halos, often found on crater walls, rims, floors closest surroundings, see Fig. -

Declaration in Support of Plaintiffs

Case: 18-36082, 02/07/2019, ID: 11183380, DktEntry: 21-12, Page 1 of 80 Case No. 18-36082 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT KELSEY CASCADIA ROSE JULIANA, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al., Defendants-Appellants. On Interlocutory Appeal Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) DECLARATION OF STEVEN W. RUNNING IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ URGENT MOTION UNDER CIRCUIT RULE 27-3(b) FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION JULIA A. OLSON PHILIP L. GREGORY (OSB No. 062230, CSB No. 192642) (CSB No. 95217) Wild Earth Advocates Gregory Law Group 1216 Lincoln Street 1250 Godetia Drive Eugene, OR 97401 Redwood City, CA 94062 Tel: (415) 786-4825 Tel: (650) 278-2957 ANDREA K. RODGERS (OSB No. 041029) Law Offices of Andrea K. Rodgers 3026 NW Esplanade Seattle, WA 98117 Tel: (206) 696-2851 Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees Case: 18-36082, 02/07/2019, ID: 11183380, DktEntry: 21-12, Page 2 of 80 I, Steven W. Running, hereby declare and if called upon would testify as follows: 1. In this Declaration, I offer my expert opinion about how excessive greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, largely from the burning of fossil fuels, are causing climate change that is dangerously warming the surface of the Earth and causing devastating impacts to the Youth Plaintiffs in this case. Because there is a decades-long delay between the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) and the resultant warming of the climate, these Youth Plaintiffs have not yet experienced the full amount of warming that will occur from emissions already released. -

List of Manuscript and Printed Sources Current Marks and Abreviations

1 1 LIST OF MANUSCRIPT AND PRINTED SOURCES CURRENT MARKS AND ABREVIATIONS * * surrounds insertions by me * * variant forms of the lemmata for finding ** (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted by me + + surrounds insertion from the addenda ++ (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted from addenda † † marks what is (I believe) certainly wrong !? marks an unidentified source reference [ro] Hogan’s Ro [=reference omitted] {1} etc. different places but within a single entry are thus marked Identical lemmata are numbered. This is merely to separate the lemmata for reference and cross- reference. It does not imply that the lemmata always refer to separate names SOURCES Unidentified sources are listed here and marked in the text (!?). Most are not important but they are nuisance. Identifications please. 23 N 10 Dublin, RIA, 967 olim 23 N 10, antea Betham, 145; vellum and paper; s. xvi (AD 1575); see now R. I. Best (ed), MS. 23 N 10 (formerly Betham 145) in the Library of the RIA, Facsimiles in Collotype of Irish Manuscript, 6 (Dublin 1954) 23 P 3 Dublin, RIA, 1242 olim 23 P 3; s. xv [little excerption] AASS Acta Sanctorum … a Sociis Bollandianis (Antwerp, Paris, & Brussels, 1643—) [Onomasticon volume numbers belong uniquely to the binding of the Jesuits’ copy of AASS in their house in Leeson St, Dublin, and do not appear in the series]; see introduction Ac. unidentified source Acallam (ed. Stokes) Whitley Stokes (ed. & tr.), Acallam na senórach, in Whitley Stokes & Ernst Windisch (ed), Irische Texte, 4th ser., 1 (Leipzig, 1900) [index]; see also Standish H. -

2019 Publication Year 2020-12-22T16:29:45Z Acceptance

Publication Year 2019 Acceptance in OA@INAF 2020-12-22T16:29:45Z Title Global Spectral Properties and Lithology of Mercury: The Example of the Shakespeare (H-03) Quadrangle Authors BOTT, NICOLAS; Doressoundiram, Alain; ZAMBON, Francesca; CARLI, CRISTIAN; GUZZETTA, Laura Giovanna; et al. DOI 10.1029/2019JE005932 Handle http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12386/29116 Journal JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH (PLANETS) Number 124 RESEARCH ARTICLE Global Spectral Properties and Lithology of Mercury: The 10.1029/2019JE005932 Example of the Shakespeare (H-03) Quadrangle Key Points: • We used the MDIS-WAC data to N. Bott1 , A. Doressoundiram1, F. Zambon2 , C. Carli2 , L. Guzzetta2 , D. Perna3 , produce an eight-color mosaic of the and F. Capaccioni2 Shakespeare quadrangle • We identified spectral units from the 1LESIA-Observatoire de Paris-CNRS-Sorbonne Université-Université Paris-Diderot, Meudon, France, 2Istituto di maps of Shakespeare 3 • We selected two regions of high Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali-INAF, Rome, Italy, Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma-INAF, Monte Porzio interest as potential targets for the Catone, Italy BepiColombo mission Abstract The MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging mission showed the Correspondence to: N. Bott, surface of Mercury with an accuracy never reached before. The morphological and spectral analyses [email protected] performed thanks to the data collected between 2008 and 2015 revealed that the Mercurian surface differs from the surface of the Moon, although they look visually very similar. The surface of Mercury is Citation: characterized by a high morphological and spectral variability, suggesting that its stratigraphy is also Bott, N., Doressoundiram, A., heterogeneous. Here, we focused on the Shakespeare (H-03) quadrangle, which is located in the northern Zambon, F., Carli, C., Guzzetta, L., hemisphere of Mercury. -

Images and Perceptions of South America, Central America and the Caribbean in Irish Culture

specializes in “Formes et Représentations en Littérature”. Teacher in a high school in La Rochelle and temporary lecturer at the university of La Rochelle Estelle Epinoux is currently working on Irish cinema, with a particular interest in aesthetics, history, identity, diaspora, space, territory, and transnationalism. Her most recent publications include: Estelle Epinoux, Frank Healy, Post-Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring new Cultural Spaces, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016; Magalie-Flores-Lonjou, Estelle Epinoux, La famille au cinéma: regards juridiques et esthétiques, Mare Martin, 2016; Estelle Epinoux, Nathalie Martinière Rewriting in the 20th WORKSHOP –21st Centuries: Aesthetic Choice or Political Act?, Michel Houdiard, 2014. She has also contributed to collective volumes, including “Le long cheminement de la rédemption en Bosnie Herzégovine” in Le silence et la parole au lendemain des guerres yougoslaves, (2015) and “Irish Cinema and Europe throughout the Twentieth Century: An Overview” in, Contemporary Irish Cinema (2011), among others. Lecturer at the Department of English Studies in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Limoges, France. Images and Perceptions Frank Healy: For many years his research was focused on the molecular basis of identity and he published extensively in this field. More recently, he has been working on the Irish diaspora in Scotland, and is involved in a project looking at soccer and nationalism. He is also involved in a research project examining the work of the contemporary Northern Irish playwright of South America, Owen McCafferty. He co-translated into French one of his plays, Mojo Mickybo (1998), which was premièred in French at the University of Tours in March 2012 and has been performed in various cities in France since then. -

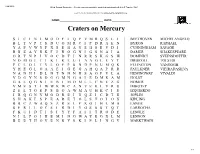

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

St. Grellan, Patron of Hy-Maine, Counties of Galway and Roscommon. John O'hanlon Introduction—Hy-Maine, Its Boundaries and O

St.Grellan,PatronofHy-Maine, counties of Galway and Roscommon. John O’Hanlon [Fifth or Sixth centuries.] CHAPTER I. Introduction—Hy-Maine, its boundaries and original inhabitants—The Firbolgs—Maine Mor succeeds and gives name to the territory—Afterwards occupied by the O’Kellys— Authorities for the acts of St. Grellan—His descent and birth—Said to have been a disciple of St. Patrick—A great miracle wrought by St. Grellan at Achadh Fionnabrach. OF this holy man Lives have been written ; while one of them is to be found in a Manu- script of the Royal Irish Academy, [1] and another among the Irish Manuscripts, in the Royal Library of Bruxelles. Extracts containing biographical memoranda relating to him are given by Colgan, [2] and in a much fuller form by Dr. John O’Donovan, as taken from the Book of Lecan. [3] There is also a notice of him, in the “ Dictionary of Christian Biography.” [4] Colgan promised to present his Life in full, at the 10th of November ; but he did not live to fulfil such promise. Besides the universal reverence and love, with which Ireland regards the memory of her great Apostle, St. Patrick, most of our provincial districts and their families of distinction have patron saints, for whom a special veneration is entertained. Among the latter, St. Grellan’s name is connected with his favoured locality. The extensive territory of Hy-Many is fairly defined, [5] by describing the northern line as running from Ballymoe, County of Galway, to Lanesborough, at the head of Lough Ree, on the River Shannon, and in the County of Roscommon. -

The Computer Analysis of Medieval Irish English

In: Raymond Hickey, Merja Kytö, Ian Lancashire and Matti Rissanen (eds) Tracing the trail of time. Proceedings of the conference on diachronic corpora, Toronto, May 1995. (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997, 167-83). The computer analysis of medieval Irish English Raymond Hickey Essen University 1. Introduction The history of English in Ireland began in the late 12th century with the coming of Norman settlers who had English speakers (along with some Welsh and Flemish) in their retinue. The long-term effect of this initial settlement was the virtually complete Anglicisation of Ireland. However this did not involve a simple substitution of Irish by English. The fortunes of English in the beginning suffered some reverses due to the resurgence of Gaelic culture in the centuries after the coming of the original settlers. This phenomenon provides the historical justification for dividing the development of English in Ireland into two main periods. The first is that of medieval Irish English which lasted from the end of the 12th to at least the 15th century and the second is the modern period which began in the early 17th century with the demise of the Gaelic social and political order as a consequence of military defeat by the English. One of the immediate effects of the latter was the spread of new varieties of English, particularly with the settlement of relatively large numbers of ‘planters’ as of the mid 17th century. At the time of the first English incursions in the latter half of the 12th century the linguistic situation in Ireland was quite homogeneous. It is true that in the 9th century Ireland was ravaged by Scandinavians just like the rest of Britain but these had settled down in the following three centuries and become assimilated with the native Irish population much as they did in other countries, such as England and France. -

Jefferson Holdridge Cv

JEFFERSON HOLDRIDGE English Dept. Wake Forest University P.O. Box 7387 Reynolda Station Winston-Salem, NC, 27109-7387 Ph: 336-758-3365 email: [email protected] EDUCATION University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland (1991-97). Ph.D. in Anglo-Irish Literature (supervisor, Prof. Declan Kiberd; external examiner, Prof. Terence Brown). Thesis on Yeats, the beautiful and the sublime, entitled Those Mingled Seas. University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland (1986-1988). M.A. in Anglo-Irish Literature. 1st class honors (supervisor, Prof. Augustine Martin; external examiner, Prof. A. N. Jeffares). Thesis on Irish and English literature of the 1890s entitled Prayers Out of the Canon. San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA (1979-1983). B.A. in English. Also concentrated on Greek and Roman mythology and literature. School of Irish Studies, Dublin, Ireland (1981-1982). Undergraduate study of the history, language, folklore and literature of Ireland. TEACHING AND RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (2002-present). Associate Professor of English and Director of Wake Forest University Press. Duties include teaching undergraduate and graduate courses on Irish literature from the 18th century to the contemporary periods, teaching intensive writing courses, introduction to literature surveys, and first-year seminars, as well as supervising WFU Press. General duties as Director of Wake Forest University Press: editing, acquisitions and management. University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland (1997-2000). Faculty of Arts Fellow in Department of Modern English. Lectured on Modernism/Postmodernism and on 18th-century to contemporary Anglo-Irish literature, ran seminars for postgraduates, taught 3rd-year tutorials, and supervised M.A. theses in Anglo-Irish literature. -

Town in the 14Th Century

URBANIZATION AND POLLUTION IN AN IRISH (?) TOWN IN THE 14TH CENTURY In this article my intention is to offer a rather different interpretation from the ones so far provided by scholars who have analysed the medieval poem known as Satire on the people of Kildare by underlining the sociological and ‘environmentalist’ concerns of the anonymous author of this work contained in MS. British Library Harley 913. The latter is a parchment codex composed of 64 folia in 12mo, which can be roughly ascribed to the first quarter of the 14th century, the terminus post quem being 1308, year of the death of Piers of Birmingham, the fierce opponent of the Irish in memoriam of whom a poem in the manuscript, which is now considered a mock-eulogy, is dedicated.1 Its pocket-size measure (140 x 91 mm.) and the items it contains, which were described by Wanley for the first time on the occasion of the cataloguing of the Harley collection, Catalogi librorum manuscriptorum Angliae et Hiberniae in unum collecti, cum indice alphabetico, which he started work on in 1708, and whose list was reproposed by Heuser,2 would lead us to presume that it was destined for personal use. It is a trilingual miscellany, containing mainly Latin texts, 16 poems written in English (but the number rises to 17 if we add the short Five hateful things, on Fl. 6v, which is not in Wanley’s list) and two in French; a linguistic composition not infrequent in other miscellanies of English origin of that age, although in Harley 913 the presence of French “is of too little importance to provide much compilatory stimulus” (Scahill 2003: 31).