Another Brick in the Wall: Public Space, Visual Hegemonic Resistance, and the Physical/Digital Continuum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is Modern Art 2014/15 Season Lisa Portes Lisa

SAVERIO TRUGLIA PHOTOGRAPHY BY PHOTOGRAPHY BY 2014/15 SEASON STUDY GUIDE THIS IS MODERN ART (BASED ON TRUE EVENTS) WRITTEN BY IDRIS GOODWIN AND KEVIN COVAL DIRECTED BY LISA PORTES FEBRUARY 25 – MARCH 14, 2015 INDEX: 2 WELCOME LETTER 4 PLAY SYNOPSIS 6 COVERAGE OF INCIDENT AT ART INSTITUTE: MODERN ART. MADE YOU LOOK. 7 CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS 8 PROFILE OF A GRAFFITI WRITER: MIGUEL ‘KANE ONE’ AGUILAR 12 WRITING ON THE WALL: GRAFFITI GIVES A VOICE TO THE VOICELESS with classroom activity 16 BRINGING CHICAGO’S URBAN LANDSCAPE TO THE STEPPENWOLF STAGE: A CONVERSATION WITH PLAYWRIGHT DEAR TEACHERS: IDRIS GOODWIN 18 THE EVOLUTION OF GRAFFITI IN THE UNITED STATES THANK YOU FOR JOINING STEPPENWOLF FOR YOUNG ADULTS FOR OUR SECOND 20 COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS SHOW OF 2014/15 SEASON: CREATE A MOVEMENT: THE ART OF A REVOLUTION. 21 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 22 NEXT UP: PROJECT COMPASS In This Is Modern Art, we witness a crew of graffiti writers, Please see page 20 for a detailed outline of the standards Made U Look (MUL), wrestling with the best way to make met in this guide. If you need further information about 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS people take notice of the art they are creating. They choose the way our work aligns with the standards, please let to bomb the outside of the Art Institute to show theirs is us know. a legitimate, worthy and complex art form born from a rich legacy, that their graffiti is modern art. As the character of As always, we look forward to continuing the conversations Seven tells us, ‘This is a chance to show people that there fostered on stage in your classrooms, through this guide are real artists in this city. -

Moral Rights: the Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2018 Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H. Chused New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Chused, Richard H., "Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz" (2018). Articles & Chapters. 1172. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters/1172 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard Chused* INTRODUCTION Graffiti has blossomed into far more than spray-painted tags and quickly vanishing pieces on abandoned buildings, trains, subway cars, and remote underpasses painted by rebellious urbanites. In some quarters, it has become high art. Works by acclaimed street artists Shepard Fairey, Jean-Michel Basquiat,2 and Banksy,3 among many others, are now highly prized. Though Banksy has consistently refused to sell his work and objected to others doing so, works of other * Professor of Law, New York Law School. I must give a heartfelt, special thank you to my artist wife and muse, Elizabeth Langer, for her careful reading and constructive critiques of various drafts of this essay. Her insights about art are deeply embedded in both this paper and my psyche. Familial thanks are also due to our son, Benjamin Chused, whose knowledge of the graffiti world was especially helpful in composing this paper. -

Prohm in Transferts, Appropriations Et Fonctions De L’Avant-Garde Dans L’Europe Intermédiaire Et Du Nord Ed

AUCUN RETOUR POSSIBLE – AN EVENT LOGIC OF THE AVANT-GARDE Alan Prohm in Transferts, appropriations et fonctions de l’avant-garde dans l’Europe intermédiaire et du Nord ed. Harri Veivo Cahiers de la Nouvelle Europe No. 16 2012 Kunst und Kamp, poster, April, 1986 Inherent in the notion of an avant-garde is the irreversibility of its measure of progress. The vector of a cultural effort need be neither straight nor singular nor without setbacks for this to be asserted: to occupy a position that has been surpassed is to not be avant-garde. It is stunning the degree to which this logic is disregarded by fans. Art historians can hardly be faulted for keeping warm the corpses of their favorite moments. It is a mortuary profession, and for many sufficiently well paid to keep up their confidence that scholars are anyway smarter than the artists they study; “We’ll be the judge of what’s dead and when.” More charitably, taking scholars as journalists, there are new sightings of the avant-garde to report every day, so we should expect the glorified blogging of peer-review journals on the topic to continue. And here, too, there is no foul. What approaches the kind of tragedy worth regretting, however, is that so many people of such lively genius should suffer their intellectual enthusiasms to be diverted, and secured off the track of any real cultural agency. The main veins of avant-garde activity in the European sphere, the now canonical cycle Futurism-Dada- Surrealism-Etcetera, gambled art and literature’s stakes in the centuries-old entitlement for a new chance at impacting the human situation. -

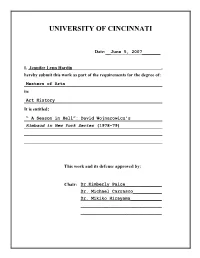

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:__June 5, 2007_______ I, Jennifer Lynn Hardin_______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Masters of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: “ A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York Series (1978-79) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr.Kimberly Paice______________ Dr. Michael Carrasco___________ Dr. Mikiko Hirayama____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud In New York Series (1978-79) A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Jennifer Hardin June 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was an interdisciplinary artist who rejected traditional scholarship and was suspicious of institutions. Wojnarowicz’s Arthur Rimbaud in New York series (1978-79) is his earliest complete body of work. In the series a friend wears the visage of the French symbolist poet. My discussion of the photographs involves how they convey Wojnarowicz’s notion of the city. In chapter one I discuss Rimbaud’s conception of the modern city and how Wojnarowicz evokes the figure of the flâneur in establishing a link with nineteenth century Paris. In the final chapters I address the issue of the control of the city and an individual’s right to the city. In chapter two I draw a connection between the renovations of Paris by Baron George Eugène Haussman and the gentrification Wojnarowicz witnessed of the Lower East side. -

5Pointz Decision

Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 1 of 100 PageID #: 4939 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------x JONATHAN COHEN, SANDRA Case No. 13-CV-05612(FB)(RLM) FABARA, STEPHEN EBERT, LUIS LAMBOY, ESTEBAN DEL VALLE, RODRIGO HENTER DE REZENDE, DANIELLE MASTRION, WILLIAM TRAMONTOZZI, JR., THOMAS LUCERO, AKIKO MIYAKAMI, CHRISTIAN CORTES, DUSTIN SPAGNOLA, ALICE MIZRACHI, CARLOS GAME, JAMES ROCCO, STEVEN LEW, FRANCISCO FERNANDEZ, and NICHOLAI KHAN, Plaintiffs, -against- G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON DECISION AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------x MARIA CASTILLO, JAMES COCHRAN, Case No. 15-CV-3230(FB)(RLM) LUIS GOMEZ, BIENBENIDO GUERRA, RICHARD MILLER, KAI NIEDERHAUSEN, CARLO NIEVA, RODNEY RODRIGUEZ, and KENJI TAKABAYASHI, Plaintiffs, -against- Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 2 of 100 PageID #: 4940 G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. -----------------------------------------------x Appearances: For the Plaintiff For the Defendant ERIC BAUM DAVID G. EBERT ANDREW MILLER MIOKO TAJIKA Eisenberg & Baum LLP Ingram Yuzek Gainen Carroll & 24 Union Square East Bertolotti, LLP New York, NY 10003 250 Park Avenue New York, NY 10177 BLOCK, Senior District Judge: TABLE OF CONTENTS I ..................................................................5 II ..................................................................6 A. The Relevant Statutory Framework . 7 B. The Advisory Jury . 11 C. The Witnesses and Evidentiary Landscape. 13 2 Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 3 of 100 PageID #: 4941 III ................................................................16 A. -

Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Joshua Carlisle Harzman University of the Pacific, [email protected]

Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research Volume 14 Article 3 2015 Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Joshua Carlisle Harzman University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope Recommended Citation Harzman, Joshua Carlisle (2015) "Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming," Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: Vol. 14 , Article 3. Available at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/kaleidoscope/vol14/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Cover Page Footnote Many thanks to all of my colleagues and mentors at the University of the Pacific; special thanks to my fiancé Kelly Marie Lootz. This article is available in Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ kaleidoscope/vol14/iss1/3 Banksy at Disneyland: Generic Participation in Culture Jamming Joshua Carlisle Harzman Culture jamming is a profound genre of communication and its proliferation demands further academic scholarship. However, there exists a substantial gap in the literature, specifically regarding a framework for determining participation within the genre of culture jamming. This essay seeks to offer such a foundation and subsequently considers participation of an artifact. First, the three elements of culture jamming genre are established and identified: artifact, distortion, and awareness. Second, the street art installment, Banksy at Disneyland, is analyzed for participation within the genre of culture jamming. -

Illstyle and Peace Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE Illstyle and Peace Productions Useful Vocabulary and Terms to Share Break beat: The beat of the most danceable section of a song. Popping: A street dance style based upon the Additional Resources technique of quickly contracting and relaxing muscles to cause a jerk in the dancer’s body Johan Kugelberg, Born in the Bronx; a visual record Locking: A dance style relying on perfect timing and of the early days of hip hop NYPL link frequent “locking” of limbs in time with music. 6 step: A basic hip-hop move in which the dancer’s Jeff Chang , Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop NYPL link arms support the body which spins in a circle above the floor. Eric Felisbret, Graffiti New York NYPL link Downrock: All breakdance moves performed with a part of the body (other than the feet) is in Bronx Rhymes interactive map contact with the floor. http://turbulence.org/Works/bronx_rhymes/what.html Smithsonian article on birth of hip-hop: http://invention.smithsonian.org/resources/online_arti Background Information for Students cles_detail.aspx?id=646 There are four essential elements of hip-hop: 5 Pointz, New York Graffiti Mecca: http://5ptz.com/ DJing: The art of spinning records and using two turn- NY Times Articles on 5 Pointz: tables to create your own instrument. http://goo.gl/i1F2I0 Also the art of touching and moving records with your hands. http://goo.gl/kOCFnv Breakdancing: A style of dancing that includes gymnastic moves, head spins, and backspins. Young 5Pointz Buzzfeed article with photos: people who were into dancing to the “breaks” at Bronx http://goo.gl/1ItqX9 parties started calling themselves B-boys and B-girls, and their style of dancing came to be known as NY Times Article on Taki183, one of the first taggers breakdancing. -

App. 1 950 F.3D 155 (2D Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals

App. 1 950 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit Maria CASTILLO, James Cochran, Luis Gomez, Bien- benido Guerra, Richard Miller, Carlo Nieva, Kenji Taka- bayashi, Nicholai Khan, Plaintiffs-Appellees, Jonathan Cohen, Sandra Fabara, Luis Lamboy, Esteban Del Valle, Rodrigo Henter De Rezende, William Tramon- tozzi, Jr., Thomas Lucero, Akiko Miyakami, Christian Cortes, Carlos Game, James Rocco, Steven Lew, Francisco Fernandez, Plaintiffs-Counter- Defendants-Appellees, Kai Niederhause, Rodney Rodriguez, Plaintiffs, v. G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 Jackson Avenue Owners, L.P., 22-52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff, Defendants-Appellants. Nos. 18-498-cv (L), 18-538-cv (CON) August Term 2019 Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York Nos. 15-cv-3230 (FB) (RLM), 13-cv-5612 (FB) (RLM), Frederic Block, District Judge, Presiding. Argued August 30, 2020 Decided February 20, 2020 Amended February 21, 2020 Attorneys and Law Firms ERIC M. BAUM (Juyoun Han, Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, Christopher J. Robinson, Rottenberg Lipman Rich, P.C., New York, NY, on the brief), Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, for Plaintiffs-Appellees. MEIR FEDER (James M. Gross, on the brief), Jones Day, New York, NY, for Defendants-Appellants. App. 2 Before: PARKER, RAGGI, and LOHIER, Circuit Judges. BARRINGTON D. PARKER, Circuit Judge: Defendants‐Appellants G&M Realty L.P., 22‐50 Jack- son Avenue Owners, L.P., 22‐52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff (collec- tively “Wolkoff”) appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York (Frederic Block, J.). -

RON ENGLISH New York, NY 10014

82 Gansevoort Street RON ENGLISH New York, NY 10014 p (212) 966 - 6675 Born 1959 in Decatur, IL allouchegallery.com Based in Beacon, NY University of North Texas; University of Texas, Austin SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Ron English at Art Wynwood, Eternity Gallery, Miami 2018 Ron English: Universal Grin, Galerie Matthew Namour, Montréal 2018 Delusionville, Allouche Gallery, New York, NY 2017 Toybox, Corey Helford Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2016 Guernica, Allouche Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Popaganda NYC Pop-Up!, Redbird NYC, New York, NY 2016 Dorothy Circus Gallery, Rome, Italy 2015 NeoNature, Corey Helford Gallery, Culver City, CA 2015 EVOLUTIONARY ALTERNATIVES, Tribeca Grand Hotel, New York, NY 2014 Ron English, From Studio to Street, Caixa Cultural, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2014 Death and the Eternal Forever, Atomica Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2014 Brandit-Popmart, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 2012 Family Tradition, MINDstyle, Los Angeles, CA 2012 Crucial Fiction, Opera Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Last Supper in South Park, Opera Gallery, New York, NY 2011 Seasons in Superbia, Corey Helford Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2011 Dim Dum Dolls, Dream in Plastic, New York, NY 2011 Skin Deep, Lazarides Rathbone, London, United Kingdom 2009 The Don Gallery, Milan, Italy 2009 MACRO Future, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Rome, Italy 2009 Immortal Underground, Opera Gallery, New York, NY 2008 Shooting Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2006 Robert Berman Gallery, Santa Monica, CA 2005 Varnish Fine Art, San Francisco, CA 2003 Robert Berman Gallery, Santa Monica, CA 2002 Minna Gallery, San Francisco, CA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2019 Here’s looking at you: modern and contemporary portraiture to fall in love with, Artsnap 2019 Street Art Collection, Artsnap 2019 Statement Piece: Recent Acquisitions and Consignments, The Missing Plinth 2019 Lucky 13 Anniversary Show, Pt. -

Together in Distance

Press Release Poster Design: Lynn Hai Together in Distance An Online Benefit Auction for COVID-19 Relief July 8–July 20, 2020 Auction Website: https://www.artspace.com/auctions/n95fornyc-benefit-auction-2020? preview=5d4ae52bce951d789e1b7f862bfdf9c7 “On this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it's up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences.” “A loveless world is a dead world.” ― Albert Camus, The Plague Ever since the beginning of 2020, our longstanding belief in the peacefulness of daily life has been shattered as the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic attacks the whole world. In May, the Press Release George Floyd Protests as part of the Black Lives Matter Movement began in Minneapolis and soon spread over not only the entire United States but across the globe. During the pandemic and the protests, more and more people have united to confront both the virus and systemic inequality. Battling natural disasters and human injustice is not heroism. It is “a matter of common decency” (Camus, 1947) that everyone should maintain. Besides supporting peaceful protests while keeping social distance, what extra efforts can we take as art professionals to help people who have been suffering? Art has always been powerful and educational for the public. Even now, when physical access to art is extremely limited, creative insights, reflections and manifestos are not constrained. On the contrary, this is a time that motivates artists to recapitulate aspects of their work and move toward new breakthroughs. It is our responsibility to struggle and explore, to look for an outlet for our anxieties or a solution to the newly disrupted reality of life, and to respond to the upheavals that have happened or are about to happen. -

Banksy Was Here: State Strategy Versus Individual Tactics in the Form of Urban Art Author: Meghan Hughes Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Title: Banksy Was Here: State Strategy Versus Individual Tactics in the Form of Urban Art Author: Meghan Hughes Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring, 2017). Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/28581 Urban art, according to Lu Pan entails a sense of “illicitness that may either pass by unnoticed or disturb the predominant order.”1 In creating this art, the ‘writers’ as they call themselves, seek to subvert the perceived framework of power represented by the city, and create alternate spaces to contest these structures outside the state-sponsored scope. Urban art seeks to subvert and disrupt normative relations between producers and consumers, by creating a space of free exchange. Through this changing and re-appropriating of space, the graffitist challenges the “illusion of ownership” and draws attention to the unseen struggle between the individual and the institutions of the metropolis.2 Using the theories of Michel de Certeau and Georg Simmel to frame my analysis, I will examine the ways in which the works of London-based urban artist Banksy engage in this practice. In exploring the ‘alternate’ spaces that Banksy creates, I seek to demonstrate how his anti-consumer, anti-political works function as avenues to negotiate and re- conceptualize relations between the individual and the structures of power represented by the city. Michel de Certeau’s work, The Practice of Everyday Life is an exploration of the daily practices, or ‘tactics’ of individuals that utilize urban space in a unique or unconventional way. -

Field Guide for Creative Placemaking in Parks

FIELD GUIDE FOR CREATIVE PLACEMAKING IN PARKS by Matthew Clarke Created by Symbolon Created by Grzegorz Oksiuta Created by Jennifer Cozzette from the Noun Project from the Noun Project from the Noun Project FIELD GUIDE FOR Copyright © 2017 by The Trust for Public Land and The City CREATIVE PLACEMAKING Parks Alliance All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be re- IN PARKS produced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embod- ied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses by Matthew Clarke permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Chief Marketing Officer,” at the address below. The Trust for Public Land 101 Montgomery Street, #900 San Francisco, CA 94104 www.tpl.org Printed in the United States of America Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data Clarke, Matthew. Field Guide for Creative Placemaking in Parks / Matthew Clarke; The Trust for Public Land and the City Parks Alliance p. cm. ISBN 978-0-692917411-00 (softbound) 1. Parks and Open Space 2. Arts and Culture. 3. Local Gov- ernment —Community Development. I. Clarke, Matthew. II. Field Guide for Creative Placemaking in Parks. forward by First Edition Lily Yeh 14 13 12 11 10 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 produced by The Trust for Public Land & City Parks Alliance FIELD GUIDE FOR CREATIVE PLACEMAKING AND PARKS TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 8 Letter Creative placemaking, as a field, has matured over the past decade.