Kanafani in Kuwait: a Clinical Cartography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acknowledgments 1 Background

NOTES Acknowledgments 1. Science and Science Policy in the Arab World , published by Centre for Arab Unity Studies 1979 and Croom Helm, 1980; and The Arab World and the Challenges of Science and Technology: Progress without Change , published by Centre for Arab Unity Studies, 1999. 1 Background 1. These numbers, as we shall see, are approximate. 2. “10 Emerging Technologies 2009,” Technology Review 102, 2 (April 2009), 37–54. 3. For a report on the ongoing debate in Germany on this issue, see Carter Dougherty, “Debate in Germany: Research or Manufacturing,” New York Times , August 12, 2009. 4. See Alvin and Heidi Toffler, Revolutionary Wealth (Currency Doubleday, 2006), 94. 5. Ibid., part 6, 146ff. 6. Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries: The Making of the Modern World (Grove Press, 2007). 7. It is speculated that the steam engine may have been invented earlier by Pharaonic priests and that knowledge of this invention was available to Hero of Alexandria at about 10 to 60 CE 8. It seems that cats became domesticated around 1450 BC and were used at that time to protect granaries in Egypt. See, for an interesting account of the cat in Egypt, Jaromir Malek, The Cat in Ancient Egypt (London: The British Museum Press, 2006), 54–55, Revised Edition. 9. Research concerning the conversion to steam shipping was already well under way. See Christine Macleod, Jeremy Stein, Jennifer Tann, and James Andrew, “Making Waves: The Royal Navy’s Management of Invention and Innovation in Steam Shipping, 1815–1832,” History and Technology , 16 (2000), 307–333. 10. Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Allen Lane, 2007). -

The Suffering of Refugees in Ghassan Kanafani's “The Child Goes to The

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2632-279X.htm ff Suffering of The su ering of refugees in refugees Ghassan Kanafani’s “The Child Goes to the Camp”: a critical appraisal Rania Mohammed Abdel Abdel Meguid Received 8 August 2020 Revised 19 September 2020 Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Arts, 18 October 2020 Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt Accepted 11 November 2020 Abstract Purpose – This paper aims to present a critical appraisal of Ghassan Kanafani’s short story “The Child Goes to the Camp” using the Appraisal Theory proposed by Martin and Rose (2007) in an attempt to investigate the predicament of the Palestinians who were forced to flee their country and live in refugee camps as well as the various effects refugee life had on them. Design/methodology/approach – Using the Appraisal Theory, and with a special focus on the categories of Attitude and Graduation, the paper aims to shed light on the plight of refugees through revealing the narrator’s suffering in a refugee camp where the most important virtue becomes remaining alive. Findings – Analysing the story using the Appraisal Theory reveals the impact refugee life has left on the narrator and his family. This story serves as a warning for the world of the suffering refugees have to endure when they are forced to flee their war-torn countries. Originality/value – Although Kanafani’ resistance literature has been studied extensively, his short stories have not received much scholarly attention. In addition, his works have not been subject to linguistic analysis. -

A Comparison of Sawt Al-Arab ("Voice of the Arabs") and A1 Jazeera News Channel

The Development of Pan-Arab Broadcasting Under Authoritarian Regimes -A Comparison of Sawt al-Arab ("Voice of the Arabs") and A1 Jazeera News Channel Nawal Musleh-Motut Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of fistory O Nawal Musleh-Motut 2006 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2006 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Approval Name: Nawal Musleh-Motut Degree: Master of Arts, History Title of Thesis: The Development of Pan-Arab Broadcasting Under Authoritarian Regimes - A Comparison of SdwzdArab ("Voice of the Arabs") and AI Jazeera News Channel Examining Committee: Chair: Paul Sedra Assistant Professor of History William L. Cleveland Senior Supervisor Professor of History - Derryl N. MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor of History Thomas Kiihn Supervisor Assistant Professor of History Shane Gunster External Examiner Assistant Professor of Communication Date Defended/Approved: fl\lovenh 6~ kg. 2006 UN~~ER~WISIMON FRASER I' brary DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational -

The Origins of Kuwait's National Assembly

THE ORIGINS OF KUWAIT’S NATIONAL ASSEMBLY MICHAEL HERB LSE Kuwait Programme Paper Series | 39 About the Middle East Centre The LSE Middle East Centre opened in 2010. It builds on LSE’s long engagement with the Middle East and provides a central hub for the wide range of research on the region carried out at LSE. The Middle East Centre aims to enhance understanding and develop rigorous research on the societies, economies, polities, and international relations of the region. The Centre promotes both specialised knowledge and public understanding of this crucial area and has outstanding strengths in interdisciplinary research and in regional expertise. As one of the world’s leading social science institutions, LSE comprises departments covering all branches of the social sciences. The Middle East Centre harnesses this expertise to promote innovative research and training on the region. About the Kuwait Programme The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a multidisciplinary global research programme based in the LSE Middle East Centre and led by Professor Toby Dodge. The Programme currently funds a number of large scale col- laborative research projects including projects on healthcare in Kuwait led by LSE Health, urban form and infrastructure in Kuwait and other Asian cities led by LSE Cities, and Dr Steffen Hertog’s comparative work on the political economy of the MENA region. The Kuwait Programme organises public lectures, seminars and workshops, produces an acclaimed working paper series, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. The Programme is funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. -

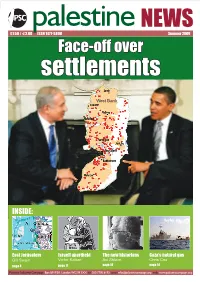

Face-Off Over Settlements

summer09 palestine NEWS 1 £1.50 / €2.00 ISSN 1477-5808 Summer 2009 Face-off over settlements West Bank INSIDE: East Jerusalem Israeli apartheid The new historians Gaza’s natural gas Gill Swain Victor Kattan Avi Shlaim Chris Cox page 4 page 11 page 14 page 18 Palestine Solidarity Campaign Box BM PSA London WC1N 3XX tel 020 7700 6192 email [email protected] web www.palestinecampaign.org 2 palestine NEWS summer09 Contents 3 Can Obama deliver? Betty Hunter examines the clash between Obama and Netanyahu over settlements 4 East Jerusalem — a stolen city Dramatic map reveals how settlements are spreading through Jerusalem 6 Q: Where are the Palestinian Ghandis? A: In Jail Bekah Wolf reports on a grassroots resistance movement — and the Israeli response 9 Trade unionists shocked and angry Kiri Tunks and Bernard Regan on a trade union delegation to the OPTs 10 BBC betrays Jeremy Bowen How the BBC Trust caved in to pressure and censured its Middle East editor Cover map: fmep_v18n1_map. pdf from the Foundation for 11 Israel guilty of colonialism and apartheid Middle East Peace. Victor Kattan on a hard-hitting South African report www.fmep.org 12 Dialogue with the Diaspora ISSN 1477 - 5808 Jeff Halper reflects on the reasons for the uproar he caused in Australia Also in this issue... 14 The ‘new history’ and the Nakba Gaza music school reopens Prof Avi Shlaim describes the impact of re-examining the past page 21 16 Operation ‘Hasbara’ Diane Langford examines how the Israeli propaganda machine manipulates the message 17 Between a rock and -

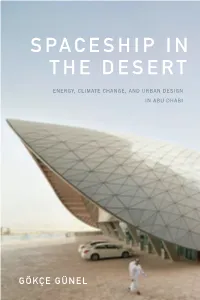

Spaceship in the Desert

SPACESHIP IN THE DESERT ENERGY, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND URBAN DESIGN IN ABU DHABI GÖKÇE GÜNEL SPACESHIP IN THE DESERT EXPERIMENTAL FUTURES Technological Lives, Scientifi c Arts, Anthropological Voices A series edited by Michael M. J. Fischer and Joseph Dumit Spaceship in the Desert Energy, Climate Change, and Urban Design in Abu Dhabi GÖKÇE GÜNEL Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Günel, Gökçe, [date] author. Title: Spaceship in the desert : energy, climate change, and urban design in Abu Dhabi / Gökçe Günel. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Experimental futures | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: lccn 2018031276 (print) | lccn 2018041898 (ebook) isbn 9781478002406 (ebook) isbn 9781478000723 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478000914 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Sustainable urban development--United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) | City planning— Environmental aspects—United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) | Technological innovations— Environmental aspects—United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) | Urban ecology (Sociology) —United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) Classifi cation: lcc ht243.u52 (ebook) | lcc ht243.u52 a28 2019 (print) ddc 307.1/16095357—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018031276 -

Britain and the Development of Professional Security Forces in the Gulf Arab States, 1921-71: Local Forces and Informal Empire

Britain and the Development of Professional Security Forces in the Gulf Arab States, 1921-71: Local Forces and Informal Empire by Ash Rossiter Submitted to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arab and Islamic Studies February 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Abstract Imperial powers have employed a range of strategies to establish and then maintain control over foreign territories and communities. As deploying military forces from the home country is often costly – not to mention logistically stretching when long distances are involved – many imperial powers have used indigenous forces to extend control or protect influence in overseas territories. This study charts the extent to which Britain employed this method in its informal empire among the small states of Eastern Arabia: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the seven Trucial States (modern day UAE), and Oman before 1971. Resolved in the defence of its imperial lines of communication to India and the protection of mercantile shipping, Britain first organised and enforced a set of maritime truces with the local Arab coastal shaikhs of Eastern Arabia in order to maintain peace on the sea. Throughout the first part of the nineteenth century, the primary concern in the Gulf for the British, operating through the Government of India, was therefore the cessation of piracy and maritime warfare. -

Kanafani's Returnee to Haifa

2021-4117-AJP – 15 FEB 2021 1 A Discursive Study of the Unscheduled Dialogue in G. 2 Kanafani’s Returnee to Haifa 3 4 In Ghassan Kanafani’s tale Returnee to Haifa, ‘What’s in a name?’ is a 5 restless question in search of an answer. Although it does not openly speak 6 to any specific situation, this question turns into a clue to understanding the 7 cross-grained narrative discourse of the tale. All of the four main characters 8 enmeshed in an untimely dialogue over identity and belonging find 9 themselves facing a multifaceted dilemma that intensifies the urge for 10 reframing the concept of identity and belonging as regards homeland and 11 blood kinship. Accordingly, this paper reviews attribution theory and refers 12 to it as a research tool to look at the significance of the messages embedded 13 in the conflicting discourses that shape the un-orchestrated dialogue through 14 which all the characters involved tend to tell and defend different versions of 15 the one story, the Palestinian Nakba1. 16 17 Keywords: Kanafani, Haifa, discourse, homeland, dialogue, memory, 18 identity 19 20 21 Introduction 22 23 “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose 24 By any other name would smell as sweet.” 25 (Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act II, sc. ii, 2) 26 27 28 „What‟s in a Name?‟ sounds too elusive for a clue used in an academic 29 research paper. However, I am not hunting for an enigmatic title to impress my 30 readers. I just came across the above quote while re-reading William 31 Shakespeare‟s Romeo and Juliet (1597) to outline my literature course syllabus 32 prescribed for undergraduate students taking my literature course (ENG311) at 33 The Lebanese American University in Beirut, Lebanon. -

Palestinian Authority, Hamas

HUMAN TWO AUTHORITIES, RIGHTS ONE WAY, ZERO DISSENT WATCH Arbitrary Arrest & Torture Under the Palestinian Authority & Hamas Two Authorities, One Way, Zero Dissent Arbitrary Arrest and Torture Under the Palestinian Authority and Hamas Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36673 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36673 Two Authorities, One Way, Zero Dissent Arbitrary Arrest and Torture Under the Palestinian Authority and Hamas Map .................................................................................................................................... i Glossary ............................................................................................................................. ii Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

2021 Esfandiary Dina 063365

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Changing security dynamics in the Persian Gulf the case of the United Arab Emirates Esfandiary, Dina Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Changing security dynamics in the Persian Gulf: The case of the United Arab Emirates PhD in War Studies Dina Esfandiary 1 Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. -

Newsletter No

Newsletter No. 1, October 2006 Available online at www.ex.ac.uk/iais 1. Forthcoming events 7. Visiting research fellows 2. Institute news 8 Library staff 3. Programme news & new modules 9. Recent PhD graduates 4. Teaching staff 10. PhD candidates 5. Emeritus & visiting professors 11. New publications by Institute members 6. Honorary research fellows 12. Book & film reviews 1. FORTHCOMING EVENTS Wednesday Lunchtime Seminars, 12:00–2:00pm, Lecture Theatre 1 The lunchtime Postgraduate Research Seminar is open to everyone. Attendance is compulsory for MPhil/PhD students in their first year. All other MPhil/PhD and MA students are encouraged to attend. Professor Rob Gleave, Director of Postgraduate Studies, is the Seminar Convener. 12:00–12:50pm 1:10–2:00pm Oct. 4 Introductory Session ‘Objectification of “Mental Networks”: The Production of Text and the Role of Patronage in a Persianate Context’ by Dr JanPeter Hartung (Universität Erfurt) Oct. 11 Training Session ‘The PalestinianJordanian Identity: a Socioeconomic Perspective’ by Luisa Gandolfo (PhD candidate, IAIS, Exeter) Oct. 18 ‘Tawfiq alHakam and the West’ by Professor Rasheed ElEnany (IAIS, Exeter) Oct. 25 Training Session ‘Boundary Disputes on the Arabian Peninsula’ by Andrew Brown (PhD candidate, IAIS, Exeter) Nov. 1 ‘Transnational Merchants in the 19 th Century Gulf: The Case of the Safar Family’ by Dr James Onley (IAIS, Exeter) Nov. 15 ‘Said alShartuni’s Contribution to the ‘The Leadership of Gamal AbdalNasir and Abdal Arabic Linguistic and Literary Heritage’ Karim Qassim’ by Anne Alexander (PhD candidate, by Abdulrazzak Patel (PhD candidate, IAIS, Exeter) IAIS, Exeter) Nov. -

Ghassan Kanafani: the Palestinian Voice of Resistance

Angloamericanae Journal Vol. 3, No. 1, 2018, pp. 12-17 http://aaj.ielas.org ISSN: 2545-4128 Ghassan Kanafani: The Palestinian Voice of Resistance Shamenaz Bano Assistant Professor, Department of English, S. S. Khanna Girls’ Degree College, Allahabad, India Received: 2018-05-10 Accepted: 2018-06-20 Published online: 2018-07-30 ______________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Ghassan Kanafani is a Palestinian writer who is has raised his voice against injustice and tyranny of Zionist regime in his writings. He is the voice of subaltern or voice of voiceless and through his writings one can easily trace out the struggle which he has undergone throughout his life but has been firm in his resolution to speak against any kind of injustice done against his countrymen. Kanafani have tried to highlight issues related to humanity through his writings. So in depiction about issues related with humanity his perspective is to raise his voice against all kinds of racism, imperialism and atrocities. In his works he has depicted characters who are trying to uplift themselves from all kinds of colonial encounters. Characters who are trying to assert their autonomy in adverse situations, who are trying to liberate themselves from various kinds of exploitation, oppression, persecution and inhuman activities, are part of their writings. Keywords: voice, resistance, subaltern, racism, imperialism. __________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction Some people are born for a cause and Kanafani is one of them. Being born in Acre, Palestine in 1936, when Palestine was a British mandate. But unfortunately in 1948, his family had to flee away from their motherland because of illegal Zionist occupation.