Alex San Diego

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCTOBER 1960 • • R St Rs (Conthiued Fi.·Om Page 1) Some :Sources in 1959 to 1960 ; Ary Increases for the Business

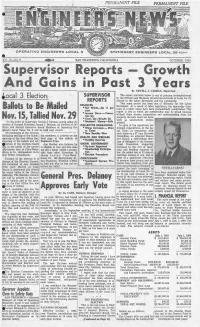

•.' _, -PERMANENT FILE '•' STATIONARY. ~ ENGfNEERS. ·. '· ... .·. -~· - .. OCTOBER,"1960 • " ~- ~- .,,.,. " J ' • •• r • • '•Ort ~ - r • :• s• "'• Past. -~ .' . --· \! . By NEWELL J. · CA~MAN, Superf isor : ·, io~aL B< Election;,, .·· ·. ;: .c. " , .' SUPElR.V.ISOR TM report-. unfolded ~ below is -~one ::. of .genuine .· accorriplfshmerit : by the Officers and Members toward improvement ·oftoc~l :N·o. 3's - .. REPORTS -~ st~tti:i-e iii: the LabOr Movement and :the community. This same p~dod _has been one of difficulty _·::1\ . :.- ~a~:-:::·-~- ·t· .. _,;·_··;_··· o~/·.:··· a-- ···- e:· < ~_:: ·· a ·ctlle:-=- .l -.-i·. · ;FiNANCES: · .. for the--Laj)or ... _. :- .. ·. ~ __1, ...:- .~ ~. '·. /: u t' Movement: As a result of labor legislation, the day-to;.day £:unc :.ye · ~q~·t W:~rt,h~Op' ll , per tions of a. labor union . · · c;ent have been.. tremendously complicated .. This · . .· .. • · . · · report is one in which · -•Income Down ;.... .Protec:- the membership m<~y be· proud because . -tici'n ·.up,·. · · · withoqt .the~r sincere --cooperation and understanding from the maj~.r,:ity tb,e task could not h<~ up-.;-:Resul!:s.Up _ve •• . Mo•~ " t5~·. l'alliid ·: Nov.,• 2~ -.>•_Cost~ '. been·· · so suec~ssfully · acc'oni- ()n the ord~i: ~ of S_up~~vis.or New ,eli. '"J~ . C~rn~a:n.; a_cting unde;, di · . • Members: , Moriey~Safe plished. · · . , r.ectlon' Qf-Ge)l'eralPresidell,t Joseph JhD_elaney~ an'electlori of' ·cott~ctrve aA.fiG~INI;i\iG - . In spite. of the significant'" ad~ · fleers and -D1§tricf Executive ·J.3oard ·.Memb€rs .of Operating . · ··wage: Increases - 'More 'd'itional expenditures of 'the1' Lo giiie$rs :· LCic<U Union ·· N:o: 3 :will b.e li~la .:ne:xtrnonth . -

30, 1981 Evefy Thuridajr 26 Pages—25 Cents 11 Wwfcu.N.1

O O\ o oc- c< : <Q 2 m o - M a Q THE WESTFIELD LEADER o J The Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper In Union County Publ[ih«d NINETY-FIRST YEAR, NO. 39 S^-ood Cbn PnUft PM WESTFIELD. NEW JERSEY,.THURSDAY, APRIL 30, 1981 Evefy Thuridajr 26 Pages—25 Cents 11 WWfcU.N.1. Y Official Balks at Town Another Sidewalk Battle Looms The battle of the Earl Lambert. project is needed to provide by the opponents is the Fairmont Ave., one of more sidewalks leading to Similar dissention oc- safe access for the walk to possibility of converting the than a dozen speakers at the Competition in Camp Market Washington School has been curred about a year ago Washington School and school system to a middle - public hearing on the or- revived—this year on the when council eventually opponents claiming their school concept which would dinance. "We don't need the Summer sports camps compete with the cost," he Jeremiah said he feared southeast side of St. Marks agreed to put sidewalks on own surveys do not warrant eliminate the two upper "Safety starts at home," Recreation Commission as a would emanate to make the said. the entrance of the Ave. between South South Chestnut St., and the the walks and subsequent grades in elementary replied Fred Gould of 716 St. competitor," William camps self-supporting and The Recreation Com- recreation' commission, or Chestnut and Sherman Sts. neighborhood was split on disruption to their schools and reduce Marks Ave. "Cost is not a Jeremiah toM Mayor Allen not dependent on tax mission proposes among its the "public factor," into a Originally scheduled for the issue. -

Proliferation of Hallyu Wave and Korean Popular Culture Across the World: a Systematic Literature Review from 2000-2019

Journal of Content, Community & Communication Amity School of Communication Vol. 11 Year 6, June - 2020 [ISSN: 2395-7514 (Print)] Amity University, Madhya Pradesh [ISSN: 2456-9011 (Online)] PROLIFERATION OF HALLYU WAVE AND KOREAN POPULAR CULTURE ACROSS THE WORLD: A SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW FROM 2000-2019 Garima Ganghariya Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication and Media Studies, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, India Dr Rubal Kanozia Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication and Media Studies, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, Punjab, India ABSTRACT The exponential growth in the popularity of Korean pop cultural products across the globe known as Hallyu wave has grabbed the attention of people worldwide. At times when the geographic boundaries have become blurred due to the virtual connectivity and advancement in internet technology, South Korean popular culture is developing at an unprecedented rate across the globe. The popularity is such that it has entered the mainstream even competing with the Hollywood films, dramas and music. The field of Hallyu though has attracted many from the academia, as it is still a newer research area, not many significant attempts have been made to review the literature in a systematic manner. The major objective of this paper is to acquire a better understanding, and a detailed review of the research regarding Hallyu wave, its allied areas, current status and trends. Systematic Literature Review (SLR) is the method used for this paper. This research has utilized the methods presented by Junior & Filho (2010), Jabbour (2013) and Seuring (2013). The researchers have deployed a systematic literature review approach to collect, analyze and synthesize data regarding the Hallyu wave, addressing a variety of topics using Google Scholar between 2000 and 2019 and selected 100 primary research articles. -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

JYP Entertainment (035900 KQ ) Margin Recovery in 3Q19 Will Be Key

JYP Entertainment (035900 KQ ) Margin recovery in 3Q19 will be key Entertainment 2Q19 review: OP slightly misses expectations, at W9.4bn Results Comment For 2Q19, JYP Entertainment announced consolidated revenue of W39.2bn (+24.1% YoY; all growth figures hereafter are YoY) and operating profit of W9.4bn (+3.9%). Operating profit was August 16, 2019 slightly below our estimate (W10.3bn) and the consensus. Revenue growth continued to be driven by the content (+40% for album/digital music) and global digital (+52% to W1.3bn for YouTube revenue) segments , and the monetization of new artists also gained traction. That said, margins contracted due to increased artist royalties and management costs (gross margin fell 4.6%p to 43.7%). While the decline was modest, these costs are affected by a (Maintain) Buy number of factors, including the terms of individual artist contracts, leverage effects from album sales, and overseas schedules. We advise keeping a close eye on any structural changes Target Price (12M, W) ▼ 28,000 through 3Q19, when revenue from TWICE’s dome tour is likely to be recognized. Share Price (08/14/19, W) 18,800 Album/digital music revenue grew 40% to W14.7bn. Album sales included 400,000 copies of TWICE’s new album, 300,000 copies of GOT7’s mini album, and 160,000 copies of Stray Kids ’ special album. Global digital music revenue grew 54% to W2bn, which included sales from the Expected Return 49% distribution partnership with The Orchard (less than W0.3bn). Concert revenue dipped 34% to W4.7bn, as attendance declined as a result of the absence of TWICE and GOT7 concerts in Japan. -

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

English-To-Korean Code Switching and Code Mixing in Korean Music Show After School Club Episode 191

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ENGLISH-TO-KOREAN CODE SWITCHING AND CODE MIXING IN KOREAN MUSIC SHOW AFTER SCHOOL CLUB EPISODE 191 AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By NATALIA PANTAS Student Number: 144214057 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2018 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ENGLISH-TO-KOREAN CODE SWITCHING AND CODE MIXING IN KOREAN MUSIC SHOW AFTER SCHOOL CLUB EPISODE 191 AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By NATALIA PANTAS Student Number: 144214057 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2018 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI GO FOR IT. NO MATTER HOW IT ENDS, IT WAS AN EXPERIENCE. -unknown- vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI Dedicated to MY BELOVED PARENTS AND KPOP FANS ALL AROUND THE WORLD viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I believe that in order to finish this thesis, we, as human beings definitely need others to support us. First of all, I would like to give thanks to Jesus Christ for His unconditional love and blessings so that I could finish this undergraduate thesis. Thank you Lord for everything You have done to me. I would like to give my deepest appreciation to my thesis advisor, Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A. for guiding me patiently in finishing my undergraduate thesis. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Fenomén K-Pop a Jeho Sociokulturní Kontexty Phenomenon K-Pop and Its

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra hudební výchovy Fenomén k-pop a jeho sociokulturní kontexty Phenomenon k-pop and its socio-cultural contexts Diplomová práce Autorka práce: Bc. Eliška Hlubinková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Filip Krejčí, Ph.D. Olomouc 2020 Poděkování Upřímně děkuji vedoucímu práce Mgr. Filipu Krejčímu, Ph.D., za jeho odborné vedení při vypracovávání této diplomové práce. Dále si cením pomoci studentů Katedry asijských studií univerzity Palackého a členů české k-pop komunity, kteří mi pomohli se zpracováním tohoto tématu. Děkuji jim za jejich profesionální přístup, rady a celkovou pomoc s tímto tématem. Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a dalších informačních zdrojů. V Olomouci dne Podpis Anotace Práce se zabývá hudebním žánrem k-pop, historií jeho vzniku, umělci, jejich rozvojem, a celkovým vlivem žánru na společnost. Snaží se přiblížit tento styl, který obsahuje řadu hudebních, tanečních a kulturních směrů, široké veřejnosti. Mimo samotnou podobu a historii k-popu se práce věnuje i temným stránkám tohoto fenoménu. V závislosti na dostupnosti literárních a internetových zdrojů zpracovává historii žánru od jeho vzniku až do roku 2020, spolu s tvorbou a úspěchy jihokorejských umělců. Součástí práce je i zpracování dvou dotazníků. Jeden zpracovává názor české veřejnosti na k-pop, druhý byl mířený na českou k-pop komunitu a její myšlenky ohledně tohoto žánru. Abstract This master´s thesis is describing music genre k-pop, its history, artists and their own evolution, and impact of the genre on society. It is also trying to introduce this genre, full of diverse music, dance and culture movements, to the public. -

The Korean Wave As a Localizing Process: Nation As a Global Actor in Cultural Production

THE KOREAN WAVE AS A LOCALIZING PROCESS: NATION AS A GLOBAL ACTOR IN CULTURAL PRODUCTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Ju Oak Kim May 2016 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Department of Journalism Nancy Morris, Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Patrick Murphy, Associate Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Dal Yong Jin, Associate Professor, School of Communication, Simon Fraser University © Copyright 2016 by Ju Oak Kim All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation research examines the Korean Wave phenomenon as a social practice of globalization, in which state actors have promoted the transnational expansion of Korean popular culture through creating trans-local hybridization in popular content and intra-regional connections in the production system. This research focused on how three agencies – the government, public broadcasting, and the culture industry – have negotiated their relationships in the process of globalization, and how the power dynamics of these three production sectors have been influenced by Korean society’s politics, economy, geography, and culture. The importance of the national media system was identified in the (re)production of the Korean Wave phenomenon by examining how public broadcasting-centered media ecology has control over the development of the popular music culture within Korean society. The Korean Broadcasting System (KBS)’s weekly show, Music Bank, was the subject of analysis regarding changes in the culture of media production in the phase of globalization. In-depth interviews with media professionals and consumers who became involved in the show production were conducted in order to grasp the patterns that Korean television has generated in the global expansion of local cultural practices. -

Cool Photographs Gbhs Gridders Roll

GBHS GRIDDERS ROLL CLARIFIED BUTTER COOL PHOTOGRAPHS Andy Creech throws 4 touchdown Food expert Gail Bowling Series of compelling photos continues passes in 7-on-7 win over Navarre, 1C touts an easy favorite, 1B with Washington Monument, 8A 219 July 5, 2012 YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER 75¢ Fire totals apartment unit after resident taken into custody Midway Fire BY MELANIE KORMONDY responded to a call at Golf Villas District Lt. Chris Special to Gulf Breeze News Apartments at 1252 College Stimmel (left) [email protected] Parkway. A fire broke out in and firefighter Apartment A while its occupant, Jimmy Skipper A domestic abuse complaint Troy Autin, 52, was outside being rescue a pet last week led to an arrest and an questioned and arrested for from an apart- apartment fire that forced the allegedly hitting his live-in girl- ment complex evacuation of numerous fright- friend. before turning No injuries resulted from the the scared ened residents in the Santa Rosa canine over to Shores neighborhood. fire. At least one pet was rescued its relieved At 7:30 p.m. on Tuesday, June from the building. owner. Photos by Steve Clark/Special to Gulf Breeze News 26, the Midway Fire Department See FIRE, Page 2A NASA Former Gulf Breeze resident Alan G. Poindexter Focus on our future Jet-ski Options for growth accident give visionaries claims plenty to digest U.S. hero ■ Former astronaut BY JOE CULPEPPER / [email protected] Alan Poindexter dies Gulf Breeze will look very different by 2062 after tragic local incident if government leadership decides to act on BY JOE CULPEPPER growth and development opportunities deter- Gulf Breeze News mined by participants in a master planning [email protected] workshop whose goal, in part, is to make the The nation this week is town America’s most livable city. -

Bromeliad Society of Australia Sat 8 July 11Am – 3.30Pm and Around the World

22,000 copies / month 7 JULY - 23RD JULY 2017 VOL 34 - ISSUE 14 The Forgotten Flotilla - story on page 4 Photo - Chania Night Sandstone MARK VINT Sales 9651 2182 Buy Direct From the Quarry 270 New Line Road Dural NSW 2158 9652 1783 [email protected] Handsplit ABN: 84 451 806 754 Random Flagging $55m2 WWW.DURALAUTO.COM 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie Community News Appointments are essential, call the Library on 4560 4460 to make a Tech savvy seniors – booking. Tax Help will be conducted at Hawkesbury Central Library, free computer classes 300 George Street, Windsor. Has the internet always been New exhibition tackles a mystery to you? Do you have difficulties using computers negative perceptions and and other technology? If so, celebrates old age then come along to any of the free computer workshops Opening on Friday, 7 July at Hawkesbury Regional Gallery in being offered at Hawkesbury Windsor is an exhibition exploring ideas, experiences and creative Central Library during August. responses to notions of ageing in our society and communities. It comprises two parts: an in-house exhibition, Time Leaves its Mark, You will be introduced to the use of tablets, shopping online safely featuring the work Jo Ernsten, Pablo Grover, Leahlani Johnson, and, sharing photos and other attachments online. Nicole Toms and David White (with a commissioned series of • Introduction to using your tablet, Friday, 11 August 1pm to 3pm, portraits of senior Hawkesbury artists), as well as a display of BYO device essential photographs titled The Art of Ageing toured by the NSW Government • Introduction to online shopping, Friday, 18 August 1pm to 3pm, Department of Family and Community Services.