Murdoch University Historical Lectures Verbatim Transcript Special Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017). -

Murdoch's Family Tree

Spring 2012 alumni magazine Murdoch’s family tree Meet some of our alumni families 1 Our family tree winners Find out about the people who have inside 4 made Murdoch into a family affair. Intouch is Murdoch University’s Commerce graduate set to soar alumni magazine for all those who Meet the new CEO of Jetstar Australia. have graduated from the University. 10 Top recruiters Find out the secrets of Murdoch 11 jobseeking success. Alumni Awards Cover: Murdoch’s family tree The 2012 winners are announced. Editor: Pepita Smyth Writers: Kylie Howard New postgraduate school Beth Jones 14 Hayley Mayne Sir Walter Murdoch School will provide the Jo Manning public policy expertise needed to solve real Martin Turner 16 world problems across a range of disciplines. Jo-Ann Whalley Photography: Rob Fyfe Liv Stockley Inprint Editorial email We preview some of the books written [email protected] by our talented alumni and staff. 18 The views expressed in Intouch are not necessarily those of Murdoch University. Intouch is produced by Murdoch University’s Corporate Communications In memorial and Public Relations Office on behalf of the Alumni Relations Office. 20We mourn the passing of one of Murdoch’s © 2012 Murdoch University founding leaders, Arthur Beacham. CRICOS Provider Code 00125J Printed on environmentally friendly paper Alumni tell their stories Catch up with the news from your22 fellow alumni. Alumni contacts 24Here you’ll find the closest alumni chapter to your home. Alumni – what’s in a name? As you may know the traditional names for graduates can be quite confusing: Alumna – one female graduate Alumnus – one male graduate Alumni – a group of graduates, male or male/female Alumnae – a group of female graduates. -

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat Greg Young This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Education and Arts Federation University University Drive, Mount Helen Ballarat 3353 Victoria, Australia STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP Except where explicit reference is made in the text this thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree of diploma. No other person’s work has been relied upon or used without due acknowledgement in the main text and bibliography. Signed (Applicant): Date: Signed (Supervisor): Date: When the intellectual and spiritual history of the nineteenth century comes to be written, a highly interesting chapter in it will be that which records the origin, growth, decline, and disappearance of the delusion of spiritualism. —Australasian Saturday 25 October 1879 Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to my University of Ballarat (now Federation University) supervisors Dr Anne Beggs Sunter, Dr Jill Blee, and Dr David Waldron for their encouragement, advice, and criticism. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge a large debt of gratitude to Professor Tony Milner and Professor John Powers, both of the Australian National University, for their generous support. This project began in the Heritage Library of the Ballaarat Mechanics’ Institute; I am grateful to the BMI for its friendly help. Dedication To Anne, Peter, Charlotte, and my teacher Dr Rafe de Crespigny. Abstract This thesis is about the origins, growth, and decline of spiritualism in nine- teenth-century Ballarat. -

John Latham in Owen Dixon's Eyes

Chapter Six John Latham in Owen Dixon’s Eyes Professor Philip Ayres Sir John Latham’s achievements are substantial in a number of fields, and it is surprising that, despite the accessibility of the Latham Papers at the National Library, no-one has written a biography, though Stuart Macintyre, who did the Australian Dictionary of Biography entry, has told me that he had it in mind at one stage. Latham was born in 1877, nine years before Owen Dixon. As a student at the University of Melbourne, Latham held exhibitions and scholarships in logic, philosophy and law, and won the Supreme Court Judges’ Prize, being called to the Bar in 1904. He also found time to captain the Victorian lacrosse team. From 1917 he was head of Naval Intelligence (lieutenant-commander), and was on the Australian staff at the Versailles Peace Conference. Latham’s personality was rather aloof and cold. Philosophically he was a rationalist. From 1922-34 he was MHR for the Victorian seat of Kooyong (later held by R G Menzies and Andrew Peacock), and federal Attorney-General from 1925-29 in the Nationalist government, and again in 1931–34 in the Lyons United Australia Party government. In addition he was Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for External Affairs from 1931-34. He resigned his seat and was subsequently appointed Chief Justice of the High Court (1935-52), taking leave in 1940-41 to go off to Tokyo as Australia’s first Minister to Japan. Latham was a connoisseur of Japanese culture. He fostered a Japan-Australia friendship society in the 1930s, and in 1934 he led an Australian diplomatic mission to Japan, arranging at that time for the visit to Australia of the Japanese training flotilla. -

Sir Walter Murdoch Memorial Lecture a Centenary Tribute Professor John Andrew La Nauze Professor of History, Australian National University

Sir Walter Murdoch Memorial Lecture A Centenary Tribute Professor John Andrew La Nauze Professor of History, Australian National University Date of Lecture: 17 September 1974 As a Western Australian, I deeply appreciate the invitation of the Vice-Chancellor of Murdoch University to speak on the day, 17 September 1974, that Murdoch University has been formally inaugurated by the Governor-General of Australia. And may I say to the Vice- Chancellor of the University of Western Australia that it is a pleasure to speak about Walter Murdoch in the Winthrop Hall where, at its first graduation ceremony, I was presented as a candidate for admission to the degree of Bachelor of Arts, though indeed in absentia. Walter Murdoch began to write an autobiography at the age of eighty-five, but he did not get far, because, he said, 'I find I have had a terribly uneventful life'. Here it is. He was born on 17 September 1874, in the Free Church Manse in Rosehearty, a fishing village in northern Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Ten years later he and his parents arrived in Melbourne. After graduating from the University of Melbourne he was first a school- teacher, then a lecturer at the University. He came to Perth early in 1913 to be the first Professor of English in the new University of Western Australia. He retired in 1939. From 1943 to 1948 he was Chancellor of the University. He lived quietly in his home in South Perth, where he died on 30 July 1970. He was well-known as a writer of essays and articles, and as a broadcaster. -

Download (116Kb)

Murdoch University Historical Lectures Verbatim Transcript Special Collections Title Inauguration ceremony of Murdoch University Speakers Mr Justice John Wickham; Emeritus Professor Noel Bayliss; Professor Stephen Griew; Sir John Kerr Series Date 17 September 1974 JW: Your Excellency, ladies and gentlemen. I will not today mention the names of all the distinguished guests present. Murdoch University extends a welcome to all the people of Western Australia whether they may be here or not, but including, among those who are here, the Deputy Premier of Western Australia, the acting Chief Justice representing the judicial branch of government both state and federal, the Leader of the Opposition, ministers of the Crown both state and federal, leaders of the churches, the Lord Mayor, and civic and other leaders. Your Excellency, Murdoch University is honoured to welcome you here, both personally and as the representative of Her Majesty the Queen. This is your first inauguration of a new university on behalf of Her Majesty and we hope that there may be many more. We also hope sir, that you will find a particular interest in this university. The work of the university will include the study of the culture, history, literature and language of Southeast Asia and of the Far East generally, and knowing of your deep interest in the affairs of this region for many years, I am sure sir, that you will be pleased to hear that among the first foreign languages to be taught at Murdoch will be Malay and Chinese. The university expends a special welcome to one person, here who's sitting in the front row; none other than Lady Murdoch. -

Australian Journal of Biography and History: No

Contents Preface iii Malcolm Allbrook ARTICLES Chinese women in colonial New South Wales: From absence to presence 3 Kate Bagnall Heroines and their ‘moments of folly’: Reflections on writing the biography of a woman composer 21 Suzanne Robinson Building, celebrating, participating: A Macdougall mini-dynasty in Australia, with some thoughts on multigenerational biography 39 Pat Buckridge ‘Splendid opportunities’: Women traders in postwar Hong Kong and Australia, 1946–1949 63 Jackie Dickenson John Augustus Hux (1826–1864): A colonial goldfields reporter 79 Peter Crabb ‘I am proud of them all & we all have suffered’: World War I, the Australian War Memorial and a family in war and peace 103 Alexandra McKinnon By their words and their deeds, you shall know them: Writing live biographical subjects—A memoir 117 Nichola Garvey REVIEW ARTICLES Margy Burn, ‘Overwhelmed by the archive? Considering the biographies of Germaine Greer’ 139 Josh Black, ‘(Re)making history: Kevin Rudd’s approach to political autobiography and memoir’ 149 BOOK REVIEWS Kim Sterelny review of Billy Griffiths, Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia 163 Anne Pender review of Paul Genoni and Tanya Dalziell, Half the Perfect World: Writers, Dreamers and Drifters on Hydra, 1955–1964 167 Susan Priestley review of Eleanor Robin, Swanston: Merchant Statesman 173 Alexandra McKinnon review of Heather Sheard and Ruth Lee, Women to the Front: The Extraordinary Australian Women Doctors of the Great War 179 Christine Wallace review of Tom D. C. Roberts, Before Rupert: Keith Murdoch and the Birth of a Dynasty and Paul Strangio, Paul ‘t Hart and James Walter, The Pivot of Power: Australian Prime Ministers and Political Leadership, 1949–2016 185 Sophie Scott-Brown review of Georgina Arnott, The Unknown Judith Wright 191 Wilbert W. -

'Murdoch Press' and the 1939 Australian Herald

Museum & Society, 11(3) 219 Arcadian modernism and national identity: The ‘Murdoch press’ and the 1939 Australian Herald ‘Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art’ Janice Baker* Abstract The 1939 Australian ‘Herald’ Exhibition of French and British Contemporary Art is said not only to have resonated ‘in the memories of those who saw it’ but to have formed ‘the experience even of many who did not’ (Chanin & Miller 2005: 1). Under the patronage of Sir Keith Murdoch, entrepreneur and managing director of the Melbourne ‘Herald’ newspaper, and curated by the Herald’s art critic Basil Burdett, the exhibition attracted large and enthusiastic audiences. Remaining in Australia for the duration of the War, the exhibition of over 200 European paintings and sculpture, received extensive promotion and coverage in the ‘Murdoch press’. Resonating with an Australian middle-class at a time of uncertainty about national identity, this essay explores the exhibition as an ‘Arcadian’ representation of the modern with which the population could identify. The exhibition aligned a desire to be associated with the modern with a restoration of the nation’s European heritage. In its restoration of this continuity, the Herald exhibition affected an antiquarianism that we can explore, drawing on Friedrich Nietzsche’s insights into the use of traditional history. Keywords: affect; cultural heritage; Herald exhibition; Murdoch press; museums The Australian bush legend and the ‘digger’ tradition both extol the Australian character as one of endurance, courage and mateship (White 1981: 127). Graeme Davison (2000: 11) observes that using this form of ‘heroic’ tradition to inspire Australian national identity represents a monumental formation of the past that is ‘the standard form of history in new nations’. -

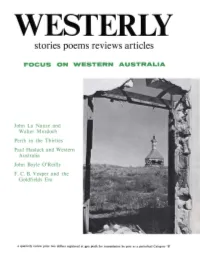

Stories Poems Reviews Articles

ESTERLY stories poems reviews articles FOCUS ON WESTERN AUSTRALIA John La Nauze and Walter Murdoch Perth in the Thirties Paul Hasluck and Western Australia John Boyle O'Reilly F. C. B. Vosper and the Goldfields Era a quarterly review price two dollars registered at gpo perth for transmission by post as a periodical Category '8 ' UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA PRESS Giving the widest representation to Western Australian writers E. J. STORMON: The Salvado Memoirs $13.95 MARY ALBERTUS BAIN: Ancient Landmarks: A Social and Economic History of the Victoria District of Western Australia 1839-1894 $12.00 G. C. BOLTON: A Fine Country to Starve In $11.00 MERLE BIGNELL: The Fruit of the Country: A History of the Shire of Gnowangerup, Western Australia $12.50 R. A. FORSYTH: The Lost Pattern: Essays on the Emergent City Sensibility in Victorian England $13.60 L. BURROWS: Browning the Poet: An Introductory Study $8.25 T. GIBBONS: Rooms in the Darwin Hotel: Studies in English Literary Criticism and Ideas 1880-1920 $8.95 DOROTHY HEWETT, ED.: Sandgropers: A Western Australian Anthology $6.25 ALEC KING: The Un prosaic Imagination: Essays and Lectures on the Study of Literature $8.95 AVAILABLE ALL GOOD BOOKSELLERS Forthcoming Publications Will Include: MERAB T AUMAN: The Chief: Charles Yelverton O'Connor IAN ELLIOT: Moondyne Joe: The Man and the Myth J. E. THOMAS & Imprisonment in Western Australia: Evolution, Theory A. STEWART: and Practice The prices set out are recommended prices only. Eastern States Agents: Melbourne University Press, P.O. Box 278, Carlton South, Victoria, 3053. WESTERLY a quarterly review EDITORS: Bruce Bennett and Peter Cowan EDITORIAL ADVISORS: Patrick Hutchings, Leonard Jolley, Margot Luke, Fay Zwicky Westerly is published quarterly by the English Department, University of Western Australia, with assistance from the Literature Board of' the Australia Council and the Western Australian Literary Fund. -

The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy

Papers on Parliament No. 42 December 2004 The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series 2003–2004 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Published by the Department of the Senate, 2004 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3164 ISSN 1031–976X ii Contents Alfred Deakin. A Centenary Tribute Stuart Macintyre 1 The High Court and the Parliament: Partners in Law-making, or Hostile Combatants? Michael Coper 13 Constitutional Schizophrenia Then and Now A.J. Brown 33 Eureka and the Prerogative of the People John Molony 59 John Quick: a True Founding Father of Federation Sir Ninian Stephen 71 Rules, Regulations and Red Tape: Parliamentary Scrutiny and Delegated Legislation Dennis Pearce 81 ‘The Australias are One’: John West Guiding Colonial Australia to Nationhood Patricia Fitzgerald Ratcliff 97 The Distinctiveness of Australian Democracy John Hirst 113 The Usual Suspects? ‘Civil Society’ and Senate Committees Anthony Marinac 129 Contents of previous issues of Papers on Parliament 141 List of Senate Briefs 149 To order copies of Papers on Parliament 150 iii Contributors Stuart Macintyre is Ernest Scott Professor of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne Michael Coper is Dean of Law and Robert Garran Professor of Law at the Australian National University. Dr A.J. -

Telling Pacific Lives

TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS Brij V. Lal & Vicki Luker Editors Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/tpl_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Telling Pacific lives : prisms of process / editors, Vicki Luker ; Brij V. Lal. ISBN: 9781921313813 (pbk.) 9781921313820 (pdf) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Islands of the Pacific--Anecdotes. Islands of the Pacific--Civilization. Islands of the Pacific--Social life and customs. Other Authors/Contributors: Luker, Vicki. Lal, Brij. Dewey Number: 990.0099 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Iles Radak [picture] [Paris : s.n., [1827] 1 print : lithograph, hand col.; 20.5 x 26 cm. nla.pic-an10412525 National Library of Australia Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface vii 1. Telling Pacic Lives: From Archetype to Icon, Niel Gunson 1 2. The Kila Wari Stories: Framing a Life and Preserving a Cosmology, Deborah Van Heekeren 15 3. From ‘My Story’ to ‘The Story of Myself’—Colonial Transformations of Personal Narratives among the Motu-Koita of Papua New Guinea, Michael Goddard 35 4. Mobility, Modernisation and Agency: The Life Story of John Kikang from Papua New Guinea, Wolfgang Kempf 51 5. -

The Building of Economics at Adelaide

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Anderson, Kym; O'Neil, Bernard Book — Published Version The Building of Economics at Adelaide Provided in Cooperation with: University of Adelaide Press Suggested Citation: Anderson, Kym; O'Neil, Bernard (2009) : The Building of Economics at Adelaide, ISBN 978-0-9806238-5-7, University of Adelaide Press, Adelaide, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/UPO9780980623857 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182254 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ www.econstor.eu Welcome to the electronic edition of The Building of Eco- nomics at Adelaide, 1901-2001. The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page.