Erosion Control on Roadsides in Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grasses Plant List

Grasses Plant List California Botanical Name Common Name Water Use Native Aristida purpurea purple three-awn Very Low X Arundinaria gigantea cane reed Low Bothriochloa barbinodis cane bluestem Low X Bouteloua curtipendula sideoats grama Low X Bouteloua gracilis, cvs. blue grama Low X Briza media quaking grass Low Calamagrostis x acutiflora cvs., e.g. Karl feather reed grass Low Foerster Cortaderia selloana cvs. pampas grass Low Deschampsia cespitosa, cvs. tufted hairgrass Low X Distichlis spicata (marsh, reveg.) salt grass Very Low X Elymus condensatus, cvs. (Leymus giant wild rye Low X condensatus) Elymus triticoides (Leymus triticoides) creeping wild rye Low X Eragrostis elliottii 'Tallahassee Sunset' Elliott's lovegrass Low Eragrostis spectabilis purple love grass Low Festuca glauca blue fescue Low Festuca idahoensis, cvs. Idaho fescue Low X Festuca mairei Maire's fescue Low Helictotrichon sempervirens, cvs. blue oat grass Low Hordeum brachyantherum Meadow barley Very Low X Koeleria macrantha (cristata) June grass Low X Melica californica oniongrass Very Low X Melica imperfecta coast range onion grass Very Low X Melica torreyana Torrey's melic Very Low X Muhlenbergia capillaris, cvs. hairy awn muhly Low Muhlenbergia dubia pine muhly Low Muhlenbergia filipes purply muhly Low Muhlenbergia lindheimeri Lindheimer muhly Low Muhlenbergia pubescens soft muhly Low Muhlenbergia rigens deer grass Low X Nassella gigantea giant needle grass Low Panicum spp. panic grass Low Panicum virgatum, cvs. switch grass Low Pennisetum alopecuroides, cvs. -

Cynodonteae Tribe

POACEAE [GRAMINEAE] – GRASS FAMILY Plant: annuals or perennials Stem: jointed stem is termed a culm – internodial stem most often hollow but always solid at node, mostly round, some with stolons (creeping stem) or rhizomes (underground stem) Root: usually fibrous, often very abundant and dense Leaves: mostly linear, sessile, parallel veins, in 2 ranks (vertical rows), leaf sheath usually open or split and often overlapping, but may be closed Flowers: small in 2 rows forming a spikelet (1 to several flowers), may be 1 to many spikelets with pedicels or sessile to stem; each flower within a spikelet is between an outer limna (bract, with a midrib) and an inner palea (bract, 2-nerved or keeled usually) – these 3 parts together make the floret – the 2 bottom bracts of the spikelet do not have flowers and are termed glumes (may be reduced or absent), the rachilla is the axis that hold the florets; sepals and petals absent; 1-6 but often 3 stamens; 1 pistil, 1-3 but usually 2 styles, ovary superior, 1 ovule – there are exceptions to most everything!! Fruit: seed-like grain (seed usually fused to the pericarp (ovary wall) or not) Other: very large and important family; Monocotyledons Group Genera: 600+ genera; locally many genera 2 slides per species WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive POACEAE [GRAMINEAE] – CYNODONTEAE TRIBE Sideoats Grama; Bouteloua curtipendula (Michx.) Torr. var. curtipendula - Cynodonteae (Tribe) Bermuda Grass; Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. (Introduced) - Cynodonteae (Tribe) Egyptian Grass [Durban Crowfoot]; Dactyloctenium aegyptium (L.) Willd (Introduced) [Indian] Goose Grass; Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. -

MSD Plant List 031009.Xlsx

Bioretention and Organic Filters Latin Name Grasses/Sedges Andropogon gerardii Big bluestem x x x 4-6 2 plum x x Bouteloua curtipendula Sideoats grama x x 1-2 1 tan Carex praegracilis* Tollway sedge x x x 1-2 1.5 tan x x x x x Carex grayii Bur sedge x x 1-2 1.5 tan x x x Carex shortiana Short's sedge x x x 2 1.5 bluish x x x x x x Carex vulpinoidea Fox sedge x x 2-3 1.5 tan x x x x x x x x x H 24 3 L L Chasmanthium latifolium River oats x x x 2-4 1.5 green Schizachyrium scoparium Little bluestem x x 2-3 1.5 bronze x x Sporobolus heterolepis Prairie dropseed x x 2-3 1.5 tan Common Name Forbs Amsonia illustris Shining bluestarGrasses/Sedges x x x 2-3 3 lt. blue x x x x x x x x x H 36 5 L H Aster novae-angliae New England aster x x 3-4 2 violet x x x x x x x x M 24 3 L H Chelone obliqua Rose turtlehead x x 3-4 2 Coreopsis lanceolata Lanceleaf coreopsis x x 1-2 1.5 yellow x x x x x x x L M Echinacea pallida Pale purple coneflower x 2-3 1.5 violet x x x x x x x L L Echinacea purpurea Purple coneflower x 2-3 1.5 violet x x x x x x x x x L L Eryngium yuccifolium Rattlesnake master 2-3 1.5 green Eupatorium coelestinum Mist flower; wild ageratum x x x 1-2 1.5 Hibiscus lasiocarpos Rose mallow x x 3-5 2.5 Iris virginica Southern blueflag iris x x 2-3 2 blue x x x x x x x H 36 4 M M Pycnanthemum tenuifolium Slender Mountain Mint x 2-3 1.5 white x x x x x x x x L H Ratibida pinnata Yellow/Grey coneflower x 3-5 1.5 yellow x x xSubmerge xd & x Emerg xent x (wate xr xdepth x in M 12 1 M H L Rudbeckia fulgida Orange coneflower x 2 2 yellow Rudbeckia hirta -

Theo Witsell Botanical Report on Lake Atalanta Park November 2013

A Rapid Terrestrial Ecological Assessment of Lake Atalanta Park, City of Rogers, Benton County, Arkansas Prairie grasses including big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and side‐oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula) thrive in a southwest‐facing limestone glade overlooking Lake Atalanta. This area, on a steep hillside east of the Lake Atalanta dam, contains some of the highest quality natural communities remaining in the park. By Theo Witsell Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission November 30, 2013 CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Background and History ................................................................................................................................ 3 Site Description ............................................................................................................................................. 4 General Description .................................................................................................................................. 4 Karst Features ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Ecological Significance .............................................................................................................................. 5 Plant Communities ................................................................................................................................... -

Grass Identification

Grass Identification The vegetation of Konza Prairie is predominantly tallgrass prairie with limited gallery forests along the larger streams. Tallgrass prairie = consists of grasses, forbs (wildflowers), shrubs and trees but the distinctive feature is the dominance of warm season grasses. Gallery forest = a forest that forms a corridor along a river or stream and projects into landscapes that are otherwise only sparsely forested such as grasslands or deserts. Most abundant warm season grasses: Big Bluestem Andropogon gerardii Little Bluestem Schizachyrium scoparium Indiangrass Sorghastrum nutans Switchgrass Panicum virgatum Sideoats Grama Bouteloua curtipendula These grasses are perennials = plants that live for many years; producing new foliage, flowers, and seeds annually. Their foliage may die back or burn completely to the soil surface each year but the vast majority of its body (“biomass”) is safely located underground. These grasses are easiest to identify when they have produced seed heads – in late July through September. These grasses are illustrated and described in the booklet “Range Grasses of Kansas” that is included in your Docent Handbook. It is also helpful to have someone knowledgeable to show you the distinguishing characteristics with the illustrations in hands. In the spring and early summer when the seed heads are not available identification of the grasses is more difficult. Here are some basic tips for grass identification (minus the seed heads): Big Bluestem: Stems are oval (not round) and often hairy at the base, grooved on one side, and covered with a whitish, waxy layer that rubs off easily (“glaucous layer” - like that seen on the skin of grapes). -

High Line Chelsea Grasslands Plant List

HIGH LINE BROUGHT TO YOU BY CHELSEA GRASSLANDS STAY CONNECTED PLANT LIST @HIGHLINENYC Trees & Shrubs Quercus macrocarpa bur oak Rosa ‘Ausorts’ Mortimer Sackler® Rose Perennials Amorpha canescens leadplant Pycnanthemum virginianum Virginia mountain mint Amsonia hubrichtii threadleaf bluestar Rudbeckia subtomentosa sweet black-eyed susan Aralia racemosa American spikenard Salvia pratensis ‘Pink Delight’ Pink Delight meadow sage Asclepias tuberosa butterfly milkweed Salvia x sylvestris ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ Rhapsody in Blue meadow sage Astilbe chinensis ‘Visions in Pink’ Visions in Pink Chinese astilbe Sanguisorba canadensis Canadian burnet Babtisia alba wild white indigo Sanguisorba obtusa ‘Alba’ Japanese burnet Babtisia x ‘Purple Smoke’ Purple Smoke false indigo Sanguisorba officinalis ‘Red Thunder’ Red Thunder burnet Dalea purpurea purple prairie clover Sedum ‘Red Cauli’ Red Cauli stonecrop Echinacea purpurea ‘Sundown’ Sundown coneflower Silphium laciniatum compass plant Eryngium yuccifolium rattlesnake master Silphium terebinthinaceum prairie dock Heuchera villosa ‘Brownies’ Brownies hairy alumroot Symphyotrichum (Aster) cordifolium blue wood aster Iris fulva copper iris Symphyotrichum (Aster) oblongifo- Raydon’s Favorite aromatic aster Knautia macedonica ‘Mars Midget’ Mars Midget pincushion plant lium Liatris pycnostachya prairie blazing star ‘Raydon’s Favorite’ Liatris spicata spiked gayfeather Symphyotrichum (Aster) laeve Bluebird smooth aster Lythrum alatum winged loosestrife ‘Bluebird’ Monada fistulosa ‘Claire Grace’ Claire Grace bergamot -

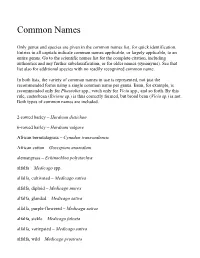

Common Names

Common Names Only genus and species are given in the common names list, for quick identification. Entries in all capitals indicate common names applicable, or largely applicable, to an entire genus. Go to the scientific names list for the complete citation, including authorities and any further subclassification, or for older names (synonyms). See that list also for additional species with no readily recognized common name. In both lists, the variety of common names in use is represented, not just the recommended forms using a single common name per genus. Bean, for example, is recommended only for Phaseolus spp., vetch only for Vicia spp., and so forth. By this rule, castorbean (Ricinus sp.) is thus correctly formed, but broad bean (Vicia sp.) is not. Both types of common names are included. 2-rowed barley – Hordeum distichon 6-rowed barley – Hordeum vulgare African bermudagrass – Cynodon transvaalensis African cotton – Gossypium anomalum alemangrass – Echinochloa polystachya alfalfa – Medicago spp. alfalfa, cultivated – Medicago sativa alfalfa, diploid – Medicago murex alfalfa, glanded – Medicago sativa alfalfa, purple-flowered – Medicago sativa alfalfa, sickle – Medicago falcata alfalfa, variegated – Medicago sativa alfalfa, wild – Medicago prostrata alfalfa, yellow-flowered – Medicago falcata alkali sacaton – Sporobolus airoides alkaligrass – Puccinellia spp. alkaligrass, lemmon – Puccinellia lemmonii alkaligrass, nuttall – Puccinellia airoides alkaligrass, weeping – Puccinellia distans alsike clover – Trifolium hybridum Altai wildrye -

Conservation Assessment for Iowa Moonwort (Botrychium Campestre)

Conservation Assessment for Iowa Moonwort (Botrychium campestre) Botrychium campestre. Drawing provided by USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region 2001 Prepared by: Steve Chadde & Greg Kudray for USDA Forest Service, Region 9 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the subject taxon or community; or this document was prepared by another organization and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Iowa Moonwort (Botrychium campestre) 2 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION/OBJECTIVES.............................................................. 4 NOMENCLATURE AND TAXONOMY .................................................. 5 DESCRIPTION OF SPECIES .................................................................... 5 LIFE HISTORY........................................................................................... -

Chapter Four: Landscaping with Native Plants a Gardener’S Guide for Missouri Landscaping with Native Plants a Gardener’S Guide for Missouri

Chapter Four: Landscaping with Native Plants A Gardener’s Guide for Missouri Landscaping with Native Plants A Gardener’s Guide for Missouri Introduction Gardening with native plants is becoming the norm rather than the exception in Missouri. The benefits of native landscaping are fueling a gardening movement that says “no” to pesticides and fertilizers and “yes” to biodiversity and creating more sustainable landscapes. Novice and professional gardeners are turning to native landscaping to reduce mainte- nance and promote plant and wildlife conservation. This manual will show you how to use native plants to cre- ate and maintain diverse and beauti- ful spaces. It describes new ways to garden lightly on the earth. Chapter Four: Landscaping with Native Plants provides tools garden- ers need to create and maintain suc- cessful native plant gardens. The information included here provides practical tips and details to ensure successful low-maintenance land- scapes. The previous three chap- ters include Reconstructing Tallgrass Prairies, Rain Gardening, and Native landscapes in the Whitmire Wildflower Garden, Shaw Nature Reserve. Control and Identification of Invasive Species. use of native plants in residential gar- den design, farming, parks, roadsides, and prairie restoration. Miller called his History of Native work “The Prairie Spirit in Landscape Landscaping Design”. One of the earliest practitioners of An early proponent of native landscap- Miller’s ideas was Ossian C. Simonds, ing was Wilhelm Miller who was a landscape architect who worked in appointed head of the University of the Chicago region. In a lecture pre- Illinois extension program in 1912. He sented in 1922, Simonds said, “Nature published a number of papers on the Introduction 3 teaches what to plant. -

Species Profile: Minnesota DNR

Species profile: Minnesota DNR events | a-z list | newsroom | about DNR | contact us Recreation | Destinations | Nature | Education / safety | Licenses / permits / regs. Home > Nature > Rare Species Guide > Keyword Search | A-Z Search | Filtered Search Botrychium campestre W.H. Wagner & Farrar ex W.H. & F. Prairie Wagner Moonwort MN Status: Basis for Listing special concern Federal Status: Botrychium campestre was first none discovered in 1982 and described eight CITES: years later (Wagner and Wagner 1990). none Until that time, no one knew that USFS: Botrychium spp. (moonworts) occurred in none prairies. The discovery sparked considerable interest among botanists in Group: finding more sites of this species, and in vascular plant trying to find out if other undescribed Class: moonworts could be found. Results have Ophioglossopsida been quite impressive; we now know that Order: B. campestre ranges across the whole Ophioglossales continent. Botanists have also discovered Family: previously undescribed species of Ophioglossaceae Botrychium from prairies and a variety of Life Form: prairie-like habitats. The actual rarity of forb B. campestre is difficult to judge at this Longevity: time. There are now numerous records, perennial but they are the result of an Leaf Duration: unprecedented search effort. Further deciduous searches will undoubtedly discover Water Regime: additional sites, and it is possible that at terrestrial some time in the future B. campestre will Soils: be thought of as relatively common. Map Interpretation sand, loam Botrychium campestre was listed as a Light: special concern species in Minnesota in full sun 1996. Habitats: Upland Prairie Description Botrychium campestre is a small, Best time to see: inconspicuous fern that can be very difficult to find. -

Seedling ID Guide for Native Prairie Plants

ABOUT THE GUIDE The goal of this guide is to help identify native plants at various stages of growth. Color photos illustrate seed, seedling, juvenile, and flowering stages, in addition to a distinguishing characteristic. Brief text provides additional identification help. Images of the seedling stage depict the appearance of a single cotyledon (first leaf) in grasses and a pair of cotyledons in broad- leaved plants, followed by photos of the first true leaves within three weeks of growth in a controlled environment. Images of the juvenile stage portray the continued development of a seedling with more fully formed leaves within the first eight weeks of shoot development . Images of the distinguishing characteristics show a specific biological feature representative of the plant. Please note that seed images do not represent the actual size of the seed. The scale is in 1/16-inch increments. Species List Big Bluestem – Andropogon gerardii Prairie Blazing Star – Liatris pycnostachya Black-Eyed Susan – Rudbeckia hirta Prairie Coreopsis – Coreopsis palmata Blue Lobelia – Lobelia siphilitica Purple Coneflower – Echinacea purpurea Butterfly Milkweed –Asclepias tuberosa Purple Prairie Clover – Dalea purpurea Cardinal Flower – Lobelia cardinalis Rattlesnake Master – Eryngium yuccifolium Compass Plant – Silphium laciniatum Rough Blazing Star – Liatris aspera Culver’s Root – Veronicastrum virginicum Rough Dropseed – Sporobolus compositus Flowering Spurge – Euphorbia corollata (asper) Foxglove Beard Tongue – Penstemon digitalis Round-headed Bushclover -

Length of Life of Roots of Ten Species of Perennial Range and Pasture Grasses

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications Agronomy and Horticulture Department 4-1946 Length of Life of Roots of Ten Species of Perennial Range and Pasture Grasses J. E. Weaver University of Nebraska-Lincoln Ellen Zink Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Weaver, J. E. and Zink, Ellen, "Length of Life of Roots of Ten Species of Perennial Range and Pasture Grasses" (1946). Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications. 500. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub/500 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agronomy and Horticulture Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Plant Physiology, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Apr., 1946), pp. 201-217 Copyright 1946 American Society of Plant Biologists LENGTH OF LIFE OF ROOTS OF TEN SPECIES OF PERENNIAL RANGE AND PASTURE GRASSES1'2 J. E. Weaver and Ellen Zink (with six figures) Introduction It is well known that death of the tops of practically all prairie grasses occurs each fall in temperate grasslands where the soil is regularly frozen. Year after year new shoots replace the old ones in this vegetation of long- lived perennials. But as to what portion of the root system is retained and over what period of time, we are almost without information. This main- tains despite the fact that much work has been done to increase our knowl- edge of the root systems of prairie grasses.