Copyright by Paola D'amora 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deutsche Songs ( Nach Titel )

Deutsche Songs ( nach Titel ) 36grad 2raumwohnung '54, '74, '90, 2006 Sportfreunde Stiller '54, '74, '90, 2010 Sportfreunde Stiller 1 2 3 4 Heute Nacht da Feiern wir Anna Maria Zimmermann 1 Tag Seer, Die 1., 2., 3. B., Bela & Roche, Charlotte 10 kleine Jägermeister Toten Hosen, Die 10 Meter geh'n Chris Boettcher 10 Nackte Friseusen Mickie Krause 100 Millionen Volt Bernhard Brink 100.000 Leuchtende Sterne Anna Maria Zimmermann 1000 & 1 Nacht Willi Herren 1000 & 1 Nacht (Zoom) Klaus Lage Band 1000 km bis zum Meer Luxuslärm 1000 Liter Bier Chaos Team 1000 mal Matthias Reim 1000 mal geliebt Roland Kaiser 1000 mal gewogen Andreas Tal 1000 Träume weit (Tornero) Anna Maria Zimmermann 110 Karat Amigos, Die 13 Tage Olaf Henning 13 Tage Zillertaler Schürzenjäger, Die 17 Jahr, blondes Haar Udo Jürgens 18 Lochis, Die 180 grad Michael Wendler 1x Prinzen, Die 20 Zentimeter Möhre 25 Years Fantastischen Vier, Die 30.000 Grad Michelle 300 PS Erste Allgemeine Verunsicherung (E.A.V.) 3000 Jahre Paldauer, Die 32 Grad Gilbert 5 Minuten vor zwölf Udo Jürgens 500 Meilen Santiano 500 Meilen von zu Haus Gunter Gabriel 6 x 6 am Tag Jürgen Drews 60 Jahre und kein bisschen weise Curd Jürgens 60er Hitmedley Fantasy 7 Detektive Michael Wendler 7 Sünden DJ Ötzi 7 Sünden DJ Ötzi & Marc Pircher 7 Tage Lang (Was wollen wir trinken) Bots 7 Wolken Anna Maria Zimmermann 7000 Rinder Troglauer Buam 7000 Rinder Peter Hinnen 70er Kultschlager-Medley Zuckermund 75 D Leo Colonia 80 Millionen Max Giesinger 80 Millionen (EM 2016 Version) Max Giesinger 99 Luftballons Nena 99 Luftballons; -

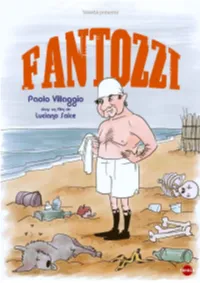

Ce N'est Pas À Moi De Dire Que Fantozzi Est L'une Des Figures Les Plus

TAMASA présente FANTOZZI un film de Luciano Salce en salles le 21 juillet 2021 version restaurée u Distribution TAMASA 5 rue de Charonne - 75011 Paris [email protected] - T. 01 43 59 01 01 www.tamasa-cinema.com u Relations Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] - 06 10 37 16 00 Fantozzi est un employé de bureau basique et stoïque. Il est en proie à un monde de difficultés qu’il ne surmonte jamais malgré tous ses efforts. " Paolo Villaggio a été le plus grand clown de sa génération. Un clown immense. Et les clowns sont comme les grands poètes : ils sont rarissimes. […] N’oublions pas qu’avant lui, nous avions des masques régionaux comme Pulcinella ou Pantalone. Avec Fantozzi, il a véritablement inventé le premier grand masque national. Quelque chose d’éternel. Il nous a humiliés à travers Ugo Fantozzi, et corrigés. Corrigés et humiliés, il y a là quelque chose de vraiment noble, n’est-ce pas ? Quelque chose qui rend noble. Quand les gens ne sont plus capables de se rendre compte de leur nullité, de leur misère ou de leurs folies, c’est alors que les grands clowns apparaissent ou les grands comiques, comme Paolo Villaggio. " Roberto Benigni " Ce n’est pas à moi de dire que Fantozzi est l’une des figures les plus importantes de l’histoire culturelle italienne mais il convient de souligner comment il dénonce avec humour, sans tomber dans la farce, la situation de l’employé italien moyen, avec des inquiétudes et des aspirations relatives, dans une société dépourvue de solidarité, de communication et de compassion. -

Risi, Così Come Monicelli, Come Scola, Come Germi E Zampa, Hanno

IL CINEMA ITALIANO, UNDICESIMA PUNTATA- LENTE D'INGRANDIMENTO SU DINO RISI- Risi, così come Monicelli, come Scola, come Germi e Zampa, hanno racchiuso nella loro lunga carriera, tante storie, tanti personaggi, tanti generi mescolati tra loro, e tantissimi messaggi diversi. Il primo che termineremo di raccontare, e approfondiremo nelle sue sfaccettature più importanti, e nelle sue opere migliori, sempre a parere di chi vi scrive, è DINO RISI. Il suo inizio è stato con VIALE DELLA SPERANZA, dove già si notavano primi vagiti del suo stile e dei suoi argomenti, dove si raccontava in maniera buffa e amara, il tentativo di alcune signorine e non solo, di farsi conoscere e avere successo nel mondo del cinema e dello spettacolo. Poi il grande successo commerciale con la terna di POVERI MA BELLI, BELLE MA POVERE, POVERI MILIONARI, storia di due simpatici burini romani,-in realtà romano lo era solo MAURIZIO ARENA, mentre RENATO SALVATORI era in origine un bagnino di VIAREGGIO, - che perdono il loro tempo, tra giochetti più o meno stupidi, e corteggiamenti a ragazze belle e prosperose come MARISA ALLASIO, la superdotata per eccellenza di quel periodo. Alla fine, le sorelle dei due burini, quella di ARENA, innamorata di SALVATORI, e quella di SALVATORI innamorata di ARENA, si faranno sposare, e faranno mettere la testa a partito,ai due giovani. Le sorelle, sono due attrici per famiglie, che faranno epoca: LORELLA DE LUCA, ALESSANDRA PANARO. Poi il grande incontro col suo alter ego, VITTORIO GASSMAN,che RISI, dirige dapprima in IL MATTATORE, vicenda di un ladruncolo e truffatore, furbo nei travestimenti. -

Titolo Anno Paese

compensi "copia privata" per l'anno 2018 (*) Per i film esteri usciti in Italia l’anno corrisponde all’anno di importazione titolo anno paese #SCRIVIMI ANCORA (LOVE, ROSIE) 2014 GERMANIA '71 2015 GRAN BRETAGNA (S) EX LIST ((S) LISTA PRECEDENTE) (WHAT'S YOUR NUMBER?) 2011 USA 002 OPERAZIONE LUNA 1965 ITALIA/SPAGNA 007 - IL MONDO NON BASTA (THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH) 2000 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 BERSAGLIO MOBILE (A VIEW TO A KILL) 1985 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 DOMANI NON MUORE MAI (IL) (TOMORROW NEVER DIES) 1997 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 SOLO PER I TUOI OCCHI (FOR YOUR EYES ONLY) 1981 GRAN BRETAGNA 007 VENDETTA PRIVATA (LICENCE TO KILL) 1989 USA 007 ZONA PERICOLO (THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS) 1987 GRAN BRETAGNA 10 CLOVERFIELD LANE 2016 USA 10 REGOLE PER FARE INNAMORARE 2012 ITALIA 10 YEARS - (DI JAMIE LINDEN) 2011 USA 10.000 A.C. (10.000 B.C.) 2008 USA 10.000 DAYS - 10,000 DAYS (DI ERIC SMALL) 2014 USA 100 DEGREES BELOW ZERO - 100 GRADI SOTTO ZERO 2013 USA 100 METRI DAL PARADISO 2012 ITALIA 100 MILLION BC 2012 USA 100 STREETS (DI JIM O'HANLON) 2016 GRAN BRETAGNA 1000 DOLLARI SUL NERO 1966 ITALIA/GERMANIA OCC. 11 DONNE A PARIGI (SOUS LES JUPES DES FILLES) 2015 FRANCIA 11 SETTEMBRE: SENZA SCAMPO - 9/11 (DI MARTIN GUIGUI) 2017 CANADA 11.6 - THE FRENCH JOB (DI PHILIPPE GODEAU) 2013 FRANCIA 110 E FRODE (STEALING HARVARD) 2003 USA 12 ANNI SCHIAVO (12 YEARS A SLAVE) 2014 USA 12 ROUND (12 ROUNDS) 2009 USA 12 ROUND: LOCKDOWN - (DI STEPHEN REYNOLDS) 2015 USA 120 BATTITI AL MINUTO (120 BETTEMENTS PAR MINUTE) 2017 FRANCIA 127 ORE (127 HOURS) 2011 USA 13 2012 USA 13 HOURS (13 HOURS: -

DINO RISI I Mostri? Sono Quelli Che Nascono in Tv

ATTUALITÀ GRANDI VECCHI PARLA DINO RISI I mostri? Sono quelli che nascono in tv Era uno psichiatra, l foglio bianco av- Intervista sorpasso e Profumo di donna, che squaderna sotto gli occhi con gelosa de- poi è diventato il padre volge il rullo del- ebbe due nomination all’Oscar, licatezza. È il campionario umano da cui Ila Olivetti Studio non riesce più a fermarsi, come sono nati i suoi film: «Suocera in fuga della commedia. 46, pronto a raccogliere una se fosse rimasto prigioniero di uno dei con la nuora sedicenne», «Eletto mister Oggi, alla soglia trama, un’invettiva, un ri- suoi film a episodi. È questa l’arte di Ri- Gay e la famiglia scopre la verità», «A cordo, ma nessuno può di- si, medico psichiatra convertito al cine- Villar Perosa due nomadi sorpresi in ca- dei 90 anni, il regista re se prima di sera sarà ne- ma, è questo che ha sempre fatto delle sa Agnelli», «Il killer s’innamora: don- spiega come vede ro d’inchiostro. Un quadro staccato dal- nostre esistenze: un collage apparente- na salva». Pubblicità di Valentino. I to- questa Italia 2006. la parete ha lasciato l’ombra sulla tap- mente senza senso, un puzzle strava- pless statuari di Sabrina Ferilli, Saman- pezzeria e il regista Dino Risi s’è risol- gante dove alla fine ogni tessera va a oc- tha De Grenet, Martina Colombari. Dai politici a Vallettopoli... to a coprire l’alone di polvere con un cupare il posto esatto assegnatole dal L’imprenditore Massimo Donadon che di STEFANO LORENZETTO patchwork di 21 immagini ritagliate dai grande mosaicista dell’universo o dal dà la caccia ai topi e il serial killer Gian- giornali. -

Natale a Miami

Natale a Miami Luigi e Aurelio De Laurentiis presentano Natale a Miami regia di NERI PARENTI Distribuzione Natale a Miami CAST ARTISTICO (crediti non contrattuali) Ranuccio Massimo Boldi Giorgio Christian De Sica Mario Massimo Ghini Stella Vanessa Hessler Paolo Francesco Mandelli Lorenzo Giuseppe Sanfelice Diego Paolo Ruffini Daniela Raffaella Bergé Tiziana Caterina Vertova CAST TECNICO Regia Neri Parenti Soggetto e Sceneggiatura Neri Parenti, Fausto Brizzi, Marco Martani Fotografia Tani Canevari Scenografia Gerry Del Monico, Maurizio Marchitelli Costumi Nicoletta Ercole e Nadia Vitali Montaggio Luca Montanari Effetti Speciali Ottici Proxima Direttore di Produzione Elisabetta Bartolomei Produttore Esecutivo Maurizio Amati Line Producer Luigi De Laurentiis Prodotto da Aurelio De Laurentiis Distribuzione Filmauro Uscita 16 dicembre 2005 Durata 100 m Per ulteriori informazioni: Ufficio Stampa Filmauro 06 69958442 pressoffice@filmauro. Natale a Miami Siamo alla vigilia delle vacanze natalizie. RANUCCIO (Massimo Boldi), GIORGIO (Christian De Sica) e PAOLO (Francesco Mandelli) hanno in comune un destino sfortunato. Tutti e tre vengono lasciati dalle rispettive mogli e compagne. Tutti e tre cadono nella stessa terribile depressione. Giorgio si rifugia tra le braccia del suo migliore amico, MARIO (Massimo Ghini) in partenza per Miami per raggiungere la sua ex moglie e la figlia STELLA (Vanessa Hessler). Decide quindi di raggiungerlo in Florida nel tentativo di dimenticare la moglie DANIELA (Raffaella Bergè). Folle di gelosia per la moglie fuggita con un altro, Giorgio sarà oggetto di spudorate seduzioni da parte di Stella, da sempre innamorata di lui. Mentre Mario dovrà inventarsi mille storie per non far scoprire all’amico un segreto imbarazzante. Ranuccio si unisce al figlio ventenne Paolo, in partenza per una eccitante vacanza a Miami con due suoi amici, DIEGO (Paolo Ruffini) e LORENZO (Giuseppe Sanfelice). -

Film Divertenti

Commedie e film comici Ciao Pussycat (regia di Clive Donner – USA, 1965) Simon Konianski (regia Micha Wald – Francia, 2009) Johnny English (regia di Peter Howitt – Regno Unito, 2003) Il favoloso mondo di Amélie (regia di Jean Pierre Jeunet – Francia, 2001) Airbag - tre uomini e un casino (regia di Juanma Bajo Ulloa – Spagna, 1997) Torrente - Il braccio idiota della legge (regia di Santiago Segura – Spagna, 1998) Il giorno della bestia (regia di Alex de la Iglesia – Spagna, 1995) La serie "The Durrells" (scritta da Simon Nye – Regno Unito, 2016-2018) Robin Hood un uomo in calzamaglia (regia di Mel Brooks – USA, 1993) Borat (regia di Larry Charles – USA, 2007) Bruno (regia di Larry Charles – USA, 2009) Tre uomini e una gamba (regia di Aldo Baglio, Giacomo Poretti, Giovanni Storti, Massimo Venier – Italia, 1997) La pazza gioia (regia di Paolo Virzì – Italia, 2016) I soliti ignoti (regia di Mario Monicelli – Italia, 1958) I mostri (regia di Dino Risi – Italia, 1963) L’armata Brancaleone (regia di Mario Monicelli – Italia, 1966) Brancaleone alle crociate (regia di Mario Monicelli – Italia, 1970) Il mio grosso grasso matrimonio greco (regia di Joel Zwick – Canada, USA, Grecia, 2002) Albeggia e non è poco (regia di José Luis Cuerda – Spagna, 1989) L'arbitro (regia di Paolo Zucca – Italia, 2013) L’uomo che comprò la luna (regia di Paolo Zucca – Italia, 2018) Non sposate le mie figlie (regia di Philippe de Chauveron – Francia, 2015) La felicità è un sistema complesso (regia di Gianni Zanasi – Italia 2015) Pecore in Erba, ovvero quando un documentario -

Nemla Italian Studies

Nemla Italian Studies Journal of Italian Studies Italian Section Northeast Modern Language Association Editor: Simona Wright The College of New Jersey Volume xxxi, 20072008 i Nemla Italian Studies (ISSN 10876715) Is a refereed journal published by the Italian section of the Northeast Modern Language Association under the sponsorship of NeMLA and The College of New Jersey Department of Modern Languages 2000 Pennington Road Ewing, NJ 086280718 It contains a section of articles submitted by NeMLA members and Italian scholars and a section of book reviews. Participation is open to those who qualify under the general NeMLA regulations and comply with the guidelines established by the editors of NeMLA Italian Studies Essays appearing in this journal are listed in the PMLA and Italica. Each issue of the journal is listed in PMLA Directory of Periodicals, Ulrich International Periodicals Directory, Interdok Directory of Public Proceedings, I.S.I. Index to Social Sciences and Humanities Proceedings. Subscription is obtained by placing a standing order with the editor at the above The College of New Jersey address: each new or back issue is billed $5 at mailing. ********************* ii Editorial Board for This Volume Founder: Joseph Germano, Buffalo State University Editor: Simona Wright, The College of New Jersey Associate Editor: Umberto Mariani, Rutgers University Assistant to the Editor as Referees: Umberto Mariani, Rugers University Federica Anichini, The College of New Jersey Daniela Antonucci, Princeton University Eugenio Bolongaro, McGill University Marco Cerocchi, Lasalle University Francesco Ciabattoni, Dalhousie University Giuseppina Mecchia, University of Pittsburgh Maryann Tebben, Simons Rock University MLA Style Consultants: Framcesco Ciabattoni, Dalhousie University Chiara Frenquellucci, Harvard University iii Volume xxxi 20072008 CONTENTS Acrobati senza rete: lavoro e identità maschile nel cinema di G. -

Del 9 Al 11 De Septiembre De 2011 Sala Mayor Del Foro De Las Ciencias Y La Artes Av. Maipú

Basso Fabio Da: Scognamiglio Giuseppe Inviato: giovedì, 25 de agosto de 2011 09:45 A: Basso Fabio; Valeri Marcello Oggetto: I: Invitación: Ciclo de cine y documentales. Alejandro Maruzzi / Maruzzi Producciones Allegati: banner 11 sep.JPG; banner 9 sep.JPG; banner 10 sep.JPG Notizia per il sito grazie Da: Consolato d'Italia in Argentina Buenos Aires Segreteria Cg [mailto:[email protected]] Inviato: giovedì 25 agosto 2011 09:12 A: Scognamiglio Giuseppe (Estero) Oggetto: Fw: Invitación: Ciclo de cine y documentales. Alejandro Maruzzi / Maruzzi Producciones ----- Original Message ----- From: Maruzzi Producciones To: [email protected] Sent: Wednesday, August 24, 2011 7:28 PM Subject: Invitación: Ciclo de cine y documentales. Alejandro Maruzzi / Maruzzi Producciones Del 9 al 11 de septiembre de 2011 Sala Mayor del Foro de las Ciencias y la Artes Av. Maipú 681 - Vicente López - Pcia. de Buenos Aires CICLO DE CINE ITALIANO Y DOCUMENTALES Semana del inmigrante Día viernes 9 de septiembre de 2011. 30/08/2011 19:00 hs. Documental de apertura: “Dall’Argentina verso l’Italia” / "De la Argentina para Italia” Historia sobre la inmigración llegada a la República Argentina y sus vivencias políticas, culturales y sociales. 20:15 hs. Documental: “Lombardia” . Breve reseña de la región Lombarda. 20:30 hs. Cinema: “Un día muy particular” / “Una giornata particolare”. Dirección: Ettore Scola. Con Marcello Mastroianni y Sofía Loren. Día sábado 10 de septiembre de 2011. 30/08/2011 14:00 hs. Cinema para chicos y grandes: “Pinocho” / “ Pinocchio”. Dirección: Roberto Benigni. Con Roberto Benigni y Nicoletta Braschi. 16:00 hs. Cinema: “El baile” / “ Le Bal”. -

I Mostri Oggi

WARNER BROS. PICTURES presenta una produzione DEAN FILM COLORADO FILM WARNER BROS. PICTURES un film di ENRICO OLDOINI con Diego Abatantuono . Sabrina Ferilli . Giorgio Panariello Claudio Bisio . Angela Finocchiaro . Carlo Buccirosso uscita: 27 marzo 2009 www.imostrioggi.it ufficio stampa film VIVIANA RONZITTI Via Domenichino 4 - 00184 ROMA 06 4819524 - 333 2393414 [email protected] materiali per la stampa su: www.kinoweb.it crediti non contrattuali scheda tecnica regia ENRICO OLDOINI soggetto e sceneggiatura FRANCO FERRINI GIACOMO SCARPELLI SILVIA SCOLA MARCO TIBERI ENRICO OLDOINI fotografia FEDERICO MASIERO montaggio MIRCO GARRONE musiche LOUIS SICILIANO suono FILIPPO PORCARI (a.i.t.s.) FEDERICA RIPANI scenografia EUGENIA F. DI NAPOLI costumi MONICA GAETANI aiuto regia FEDERICA MARSICANO casting BARBARA GIORDANI (u.i.c.) organizzatore generale ANTONIO TACCHIA prodotto da PIO ANGELETTI ADRIANO DE MICHELI MAURIZIO TOTTI distribuzione WARNER BROS. PICTURES ITALIA nazionalità ITALIANA anno di produzione 2008 - 2009 durata film 102’ cast artistico DIEGO ABATANTUONO Diego, Daniel, prelato, padrone, Davide, pirata SABRINA FERILLI Sabrina, mamma, Alice, moglie GIORGIO PANARIELLO Remo, Giorgio, Emilio, Gino, Malconcio CLAUDIO BISIO Claudio, paziente, Enzo, marito ANGELA FINOCCHIARO Renzina, Angela, analista, dama golf CARLO BUCCIROSSO Carlo, Michele, Gregorio, sotto 2 cast artistico per episodi • ruoli per ogni episodio FERRO 6 RAZZA SUPERIORE ANGELA FINOCCHIARO dama golf VALERIA DE FRANCISCIS aristocratica DIEGO ABATANTUONO Diego TUSHAR -

Una Produzione R.T.I. Prodotto Da RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI DIEGO

una produzione R.T.I. prodotto da RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI DIEGO ABATANTUONO in con ALESSIA MARCUZZI e ANTONIO CATANIA FABIO FULCO VITTORIA PIANCASTELLI GENNARO DIANA ELENA CANTARONE UGO CONTI RICCARDO ZINNA e con DINO ABBRESCIA con la partecipazione di LUIGI MARIA BURRUANO con la partecipazione di AMANDA SANDRELLI Soggetto di serie GRAZIANO DIANA, ENRICO OLDOINI, SALVATORE BASILE, GIANCARLO DE CATALDO Soggetti e sceneggiature GIANCARLO DE CATALDO, GRAZIANO DIANA, FRANCO FERRINI, ENRICO OLDOINI, CARLO BELLAMIO, MARCO TIBERI Prodotto da ANGELO RIZZOLI Regia di ENRICO OLDOINI serie tv in 4 puntate in onda in prima serata su CANALE 5 venerdì 4, 11, 18 e 25 maggio 2007 CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI CAST ARTISTICO PRINCIPALE Diego Abatantuono (Giudice Diego Mastrangelo) Alessia Marcuzzi (Claudia Nicolai) Antonio Catania (Uelino) Fabio Fulco (Paolo Parsani) Vittoria Piancastelli (Cristiana Mastrangelo) Gennaro Diana (Naselli) Dino Abbrescia (Gerardo) Elena Cantarone (Finzi) Ugo Conti (Palmieri) Riccardo Zinna (Frappampina) Luigi Maria Burruano (Procuratore De Cesare) Melissa Satta (Francesca) Amanda Sandrelli (Federica Denza) CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI CAST TECNICO Soggetto di serie GRAZIANO DIANA ENRICO OLDOINI SALVATORE BASILE GIANCARLO DE CATALDO Soggetti e Sceneggiature CARLO BELLAMIO GIANCARLO DE CATALDO GRAZIANO DIANA FRANCO FERRINI ENRICO OLDOINI MARCO TIBERI casting director FRANCO ALBERTO CUCCHINI Face ON suono FABRIZIO ANDREUCCI organizzatore di produzione EMANUELE EMILIANI costumi PATRIZIA CHERICONI FLORENCE EMIR scenografia MARISA RIZZATO musiche PIVIO & ALDO DE SCALZI montaggio FABIO e JENNY LOUTFY fotografia SANDRO GROSSI organizzatore generale ALESSANDRO LOY delegato di produzione R.T.I. FABIANA MOCCIA produttori R.T.I. MARCO MARCHIONNI ALESSANDRA SILVERI prodotto da ANGELO RIZZOLI per RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI S.p.A. regia di ENRICO OLDOINI UFFICIO STAMPA RIZZOLI AUDIOVISIVI: UFFICIO STAMPA MEDIASET: ENRICO LUCHERINI Maria Cristina de Caro TEL. -

Die Toten Hosen Armee Der Verlierer / Bommerlunder / Opel Gang Mp3, Flac, Wma

Die Toten Hosen Armee Der Verlierer / Bommerlunder / Opel Gang mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Armee Der Verlierer / Bommerlunder / Opel Gang Country: Germany Released: 1983 Style: Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1696 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1453 mb WMA version RAR size: 1302 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 234 Other Formats: DTS XM VOC MP1 MPC FLAC MP3 Tracklist A Armee Der Verlierer 4:22 B1 Bommerlunder 2:56 B2 Opel Gang 1:56 Notes This is a repress of the First release It was released in a picture sleeve. The front sleeve shows an image of the first release with the Bommerlunder bottle. But this edition was not released with the bottle. Lyrics are printed on the front cover. Track durations are not stated on release. Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: GEMA Label Code: LC 9794 Matrix / Runout (Runout side A, stamped): 668330 - A1 Matrix / Runout (Runout side B, stamped): 668330 - B1 Matrix / Runout (Printed on label side A): 7 F 668.330 A Matrix / Runout (Printed on label side B): 7 F 668.330 B Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Armee Der Verlierer / Die Toten Tot 3 Bommerlunder / Opel Gang Totenkopf Tot 3 Germany 1983 Hosen (7", Single, S/Edition) 1C 016-1651 Die Toten Bommerlunder / Opel Gang 1C 016-1651 Totenkopf Germany 1983 727 Hosen (7", Single, RE) 727 108 214, 108 Die Toten Bommerlunder / Opel Gang Virgin, 108 214, 108 Europe 1986 214-100 Hosen (7", Single, RE) Virgin 214-100 Related Music albums to Armee Der Verlierer / Bommerlunder / Opel Gang by Die Toten Hosen Ernest Clinton - Na Na Na Gang Gang Gang Inner Sleeve - I Know Die Toten Hosen - 3 Akkorde Für Ein Halleluja Die Toten Hosen - Azzurro Jackie Opel / Roland Alphonso - A Love To Share / Devoted To You Die Toten Hosen - Live In Zürich Die Toten Hosen - Unter Falscher Flagge Hartmut Kiesewetter - Musikalische Impressionen Aus Dem Norden Die Toten Hosen - Punk Rock Jackie Opel / Hortence And Jackie - Solid Rock / Stand By Me Die Toten Hosen - Live In Hultsfred 11.08.1994 Hultsfreds Festival Jackie Opel / John Holt - Eternal Love.