Textbooks, Museums and the Debates Over History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-Commencement-Program.Pdf

One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement JUNE 19, 2020 One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement 11 A.M. CDT, FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2020 2982_STUDAFF_CommencementProgram_2020_FRONT.indd 1 6/12/20 12:14 PM UNIVERSITY SEAL AND MOTTO Soon after Northwestern University was founded, its Board of Trustees adopted an official corporate seal. This seal, approved on June 26, 1856, consisted of an open book surrounded by rays of light and circled by the words North western University, Evanston, Illinois. Thirty years later Daniel Bonbright, professor of Latin and a member of Northwestern’s original faculty, redesigned the seal, Whatsoever things are true, retaining the book and light rays and adding two quotations. whatsoever things are honest, On the pages of the open book he placed a Greek quotation from the Gospel of John, chapter 1, verse 14, translating to The Word . whatsoever things are just, full of grace and truth. Circling the book are the first three whatsoever things are pure, words, in Latin, of the University motto: Quaecumque sunt vera whatsoever things are lovely, (What soever things are true). The outer border of the seal carries the name of the University and the date of its founding. This seal, whatsoever things are of good report; which remains Northwestern’s official signature, was approved by if there be any virtue, the Board of Trustees on December 5, 1890. and if there be any praise, The full text of the University motto, adopted on June 17, 1890, is think on these things. from the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Philippians, chapter 4, verse 8 (King James Version). -

An Ideological Analysis of the Birth of Chinese Indie Music

REPHRASING MAINSTREAM AND ALTERNATIVES: AN IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BIRTH OF CHINESE INDIE MUSIC Menghan Liu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Esther Clinton © 2012 MENGHAN LIU All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis project focuses on the birth and dissemination of Chinese indie music. Who produces indie? What is the ideology behind it? How can they realize their idealistic goals? Who participates in the indie community? What are the relationships among mainstream popular music, rock music and indie music? In this thesis, I study the production, circulation, and reception of Chinese indie music, with special attention paid to class, aesthetics, and the influence of the internet and globalization. Borrowing Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding/decoding, I propose that Chinese indie music production encodes ideologies into music. Pierre Bourdieu has noted that an individual’s preference, namely, tastes, corresponds to the individual’s profession, his/her highest educational degree, and his/her father’s profession. Whether indie audiences are able to decode the ideology correctly and how they decode it can be analyzed through Bourdieu’s taste and distinction theory, especially because Chinese indie music fans tend to come from a community of very distinctive, 20-to-30-year-old petite-bourgeois city dwellers. Overall, the thesis aims to illustrate how indie exists in between the incompatible poles of mainstream Chinese popular music and Chinese rock music, rephrasing mainstream and alternatives by mixing them in itself. -

Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies in Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Timothy Robert Clifford University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clifford, Timothy Robert, "In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2234. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 For more information, please contact [email protected]. In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Abstract The rapid growth of woodblock printing in sixteenth-century China not only transformed wenzhang (“literature”) as a category of knowledge, it also transformed the communities in which knowledge of wenzhang circulated. Twentieth-century scholarship described this event as an expansion of the non-elite reading public coinciding with the ascent of vernacular fiction and performance literature over stagnant classical forms. Because this narrative was designed to serve as a native genealogy for the New Literature Movement, it overlooked the crucial role of guwen (“ancient-style prose,” a term which denoted the everyday style of classical prose used in both preparing for the civil service examinations as well as the social exchange of letters, gravestone inscriptions, and other occasional prose forms among the literati) in early modern literary culture. This dissertation revises that narrative by showing how a diverse range of social actors used anthologies of ancient-style prose to build new forms of literary knowledge and shape new literary publics. -

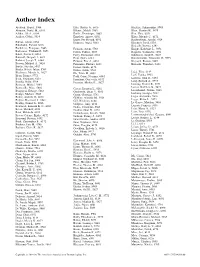

Author Index

Author Index Al-Abed, Yousef, 5904 Ellis, Shirley A., 6016 Khailaie, Sahamoddin, 5983 Altmann, Daniel M., 6041 Ellouze, Mehdi, 5863 Khan, Shaniya H., 5873 Ashkar, Ali A., 6184 Emilie, Dominique, 5863 Kim, Nina, 6031 Auffray, Ce´dric, 5914 Engelsen, Agnete, 6192 Kines, Rhonda C., 6172 Enger, Per Øyvind, 6192 Kirshenbaum, Arnold, 5924 Babian, Artem, 6184 Ezquerra, Angel, 5883 Klarquist, Jared, 6124 Babrzadeh, Farbod, 6016 Kmiecik, Justyna, 6192 Bachelerie, Franc¸oise, 5863 Fabisiak, Adam, 5763 Knight, Katherine L., 5951 Badovinac, Vladimir P., 5873 Fallon, Padraic, 6103 Koguchi, Yoshinobu, 5894 Baker, Steven F., 6031 Favry, Emmanuel, 6041 Kohlmeier, Jacob E., 5827 Bancroft, Gregory J., 6041 Feau, Sonia, 6124 Konstantinidis, Diamantis G., 5973 Barbieri, Joseph T., 6144 Feldsott, Eric A., 6031 Krzysiek, Roman, 5863 Beaven, Michael A., 5924 Fernandes, Philana, 6103 Kurosaki, Tomohiro, 6152 Bertho, Nicolas, 5883 Ferrari, Guido, 6172 Binder, Robert Julian, 5765 Fichna, Jakub, 5763 Lajqi, Trim, 6135 Blackman, Marcia A., 5827 Flo, Trude H., 6081 Lam, Tonika, 5933 Blom, Bianca, 5772 Fodil-Cornu, Nassima, 6061 Lambris, John D., 6161 Bock, Stephanie, 6135 Franchini, Genoveffa, 6172 Lang, Richard A., 5973 Bonilla, Nelly, 5914 Freeman, Michael L., 5827 Bonneau, Michel, 5883 Lanning, Dennis K., 5951 Lanzer, Kathleen G., 5827 Bonneville, Marc, 5816 Garcia, Brandon L., 6161 Lecardonnel, Je´roˆme, 5883 Bouguyon, Edwige, 5883 Geisbrecht, Brian V., 6161 Leclercq, Georges, 5997 Bourge, Mickael, 5883 Genin, Christian, 5781 Le´ger, Alexandra, 5816 Bowie, Andrew G., 6090 Gilfillan, Alasdair M., 5924 Legge, Kevin L., 5873 Boyton, Rosemary J., 6041 Gill, Navkiran, 6184 Le Gorrec, Madalen, 5816 Bradley, Daniel G., 6016 Gillgrass, Amy, 6184 Legoux, Franc¸ois, 5816 Bramwell, Kenneth K. -

Zhou-Master.Pdf (1.441Mb)

Are You a Good Chinese Musician? The Ritual Transmission of Social Norms in a Chinese Reality Music Talent Show Miaowen Zhou Master’s Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 - 60 Credits) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2015 © Miaowen Zhou 2015 Are You a Good Chinese Musician? The Ritual Transmission of Social Norms of a Chinese Reality Music Talent Show http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo II Abstract The sensational success of a Chinese reality music talent show, Super Girls’ Voice (SGV), in 2005 not only crowned many unknown Chinese girls/women with the hail of celebrity overnight, but also caused hot debates on many subjects including whether the show triggered cultural, even political democracy in China. 10 years have passed and China is in another heyday of reality music talent shows. However, the picture differs from before. For instance, not everybody can take part in it anymore. And the state television China Central Television (CCTV) joined the competition for market share. It actually became a competitive player of “reality” by claiming to find the best original and creative Chinese musicians whose voices CCTV previously avoided or oppressed. In this thesis, I will examine one CCTV show, The Song of China (SOC), in order to examine what the norms of good Chinese music and musicians are in the context of reality music talent shows. My work will hopefully give you some insights into the characteristics and the wider social and political influences of such reality music talent shows in the post-SGV era. -

Interim Results Announcement for the Six Months Ended 30 June 2020

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2020 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS • On a comparative basis (excluding the one-off profit and loss not related to operation for the corresponding period last year), the net profit attributable to equity holders increased by approximately 22% to RMB683 million, and the net profit margin raised from 9.0% to 11.1%; Including the one-off profit and loss not related to operation for the corresponding period last year, reported net profit attributable to equity holders decreased by approximately 14% and the net profit margin dropped from 12.7% to 11.1%. • Notwithstanding the impact of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (“COVID-19”) leading to a very challenging retail environment during most time of the period: – Revenue decreased slightly by approximately 1% to RMB6,181 million – Gross profit margin decreased by 0.2 percentage point – The operating leverage has been enhanced continuously, while the operating profit margin has been driven to 14.5% and increased by over 300 basis points – Achieve positive operating cash flow of RMB479 million – Continued improvement in working capital: Gross average working capital improved (reduced) by 7% while revenue decreased by approximately 1% Cash conversion cycle further improved (shortened) by 2 days (2019: 32 days/2020: 30 days) OPERATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS • Operation performance was negatively affected due to COVID-19 pandemic. -

Musical Taiwan Under Japanese Colonial Rule: a Historical and Ethnomusicological Interpretation

MUSICAL TAIWAN UNDER JAPANESE COLONIAL RULE: A HISTORICAL AND ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION by Hui‐Hsuan Chao A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, Chair Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Jennifer E. Robertson Associate Professor Amy K. Stillman © Hui‐Hsuan Chao 2009 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout my years as a graduate student at the University of Michigan, I have been grateful to have the support of professors, colleagues, friends, and family. My committee chair and mentor, Professor Joseph S. C. Lam, generously offered his time, advice, encouragement, insightful comments and constructive criticism to shepherd me through each phase of this project. I am indebted to my dissertation committee, Professors Judith Becker, Jennifer Robertson, and Amy Ku’uleialoha Stillman, who have provided me invaluable encouragement and continual inspiration through their scholarly integrity and intellectual curiosity. I must acknowledge special gratitude to Professor Emeritus Richard Crawford, whose vast knowledge in American music and unparallel scholarship in American music historiography opened my ears and inspired me to explore similar issues in my area of interest. The inquiry led to the beginning of this dissertation project. Special thanks go to friends at AABS and LBA, who have tirelessly provided precious opportunities that helped me to learn how to maintain balance and wellness in life. ii Many individuals and institutions came to my aid during the years of this project. I am fortunate to have the friendship and mentorship from Professor Nancy Guy of University of California, San Diego. -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY Chen Duxiu's Early Years: The Importance of Personal Connections in the Social and Intellectual Transformation of China 1895-1920 by Anne Shen Chap A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: Richar^TTSmith, Chair, Professor History, George and Nancy Rupp Professor of Humanities Nanxiu Qian,Associate Professor" Chinese Literature '^L*~* r^g^- ^J-£L&~^T Sarah Thai, Associate Professor History, University of Wisconsin- Madison HOUSTON, TEXAS APRIL 2009 UMI Number: 3362139 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform 3362139 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI48106-1346 ABSTRACT Chen Duxiu's Early Years: The Importance of Personal Connections in the Social and Intellectual Transformation of China 1895-1920 by Anne Shen Chao Chen Duxiu (1879-1942), is without question one of the most significant figures in modern Chinese history. Yet his early life has been curiously neglected in Western scholarship. In this dissertation I examine the political, social and intellectual networks that played such an important role in his early career—a career that witnessed his transformation from a classical scholar in the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), to a reformer, to a revolutionary, to a renowned writer and editor, to a university dean, to a founder of the Chinese Communist Party, all in the space of about two decades. -

Hainan Airlines Inflight Entertainment Magazine Sep. 2019

Hainan Airlines Inflight Entertainment Magazine Sep. 2019 200+ 600+ 1300 Movies TV Shows CDs 主 题 THEME director Robert Rodriguez. The first thing that hits “ 逆水行舟,不进则退。” “Swim against the tide, and don’t look back.” you is the exceptional energy in the action scenes, and having the great James Cameron as co-producer provides 我们可能没有机会成为超级巨星或者超级英雄, a guarantee of top-class special effects and cinematic 但是在影视剧中,我们能看到和体会到巨星和英雄 world-building. The story is set in the 26th century, 们从不言败的人生。一个人的人生不论取得的成就 at a time when danger lurks around every corner and 大与小,都需要经历各种各样的挑战,人生就是一 the lives of cyborgs hang in the balance. Alita is one of them. With the help of Dr. Daisuke Ido, Alita must find 场战斗,有时候不仅需要越战越勇,更需要越挫越勇。 herself in this unfamiliar world, while also doing battle 本期电影中的主人公们都在同命运做抗争,也都各 against a powerful enemy in order to build a future for 有各的不凡之处。 cyborgs. Alita has incredible fighting abilities and, after We may not get the chance to become superstars or unlocking her strength, goes on to change the face of superheroes in our own lives, but on TV and in the the whole world. movies, we get to see and experience the indomitable spirit of both kinds of people. No matter whether an 才艺不凡——《波西米亚狂想曲》。这部皇后 individual’s accomplishments are great or small, they still 乐队的传记片为我们重现了摇滚巨星佛莱德·摩克瑞 have to face up to many different kinds of challenges. 的心路历程。家庭普通、外貌丑陋,但一副好嗓子, Life is a battle, and sometimes it’s not enough to face 以及对音律的敏感,让他从机场的打工仔摇身一变 battle with bravery. What’s more important is to face 成为了音乐界的天之骄子。生活上,他情感经历曲折, failure with bravery. -

Alumni Chapter Sharing 36

ALUMNI CHAPTER SHARING 36 Alumni Chapter Sharing e are pleased to bring you the new “Alumni Chapter/Club” section of TheLINK where we introduce you to long-serving members of CEIBS’ alumni organisations as they share their experiences and lessons learned over the years. In this issue, we feature the CEIBS Shanghai Chapter W(International), the Guangxi Alumni Chapter and the CEIBS Golf Club. The CEIBS Alumni Association Shanghai Chapter (International) was established in November 2016, providing a “home” for the school’s English-speaking alumni. The Guangxi Alumni Chapter, though located thousands of miles away from the school’s main campuses, is a close-knit and friendly group of people who are full of positive energy. They are actively involved in supporting both their alma mater’s development and working for the public good. Persistence has paid off for the CEIBS Golf Club! After more than a decade of trying, they took the championship during the China Top Schools EMBA Golf League Competition. Keep an eye out for this section in future issues as we bring you stories about other CEIBS alumni organisations. And be sure to drop us a line at [email protected] if you have content or story ideas to contribute. TheLINK Volume 1, 2017 ALUMNI CHAPTER SHARING 37 International Alumni Association Spreads its Wings By Verena Kohleick & Sneha Das aunched last November as a plus countries around the globe “home” for English-speaking participating in the various events LCEIBS alumni as they work hosted by more than 60 alumni with and within the wider CEIBS chapters, CEIBS is proud of its community, the CEIBS Alumni international alumni portfolio. -

Hainan Airlines Inflight Entertainment Magazine Oct. 2019

Hainan Airlines Inflight Entertainment Magazine Oct. 2019 200+ 600+ 1300 Movies TV Shows CDs THEME 主 题 When拨云见日 the clouds clear, a bright 未来可期 and hopeful future is revealed 十月已至,秋光潋滟,万物美好。 October has arrived, bringing with it the light and colors of autumn. 这是一段充满收获的时间,积累了大半年能量的果 实总算落了地,但再转身你可能就要面对满眼的万物凋 零。我们就是在过着这种“又丧又有希望”的平凡小日 子,连影视剧中的主人公们也不例外,即使身披霞光、 手握星辉,也终将面对成长、家庭、爱情等凡人琐事。 也许,这正是我们爱电影的原因,不论多么宏大的主题, 我们总能在其中找到生活的影子,给我们力量,直面过 去,也能笑迎未来。 Autumn is the season of the harvest, where fruit full of stored up energy from the preceding months finally falls to the ground. But as soon as the fruit falls, it begins to wither away. We live with this "loss and hope" in our daily lives, and characters in movies and television series are no exception. They too eventually have to face trivial matters such as growth, family and love just like any other person. This is perhaps why we love movies. No matter how fantastical the theme of a movie is, we can always find aspects of life reflected in it, giving us strength to face the past and to have hope for the future. 本期的几部好莱坞大片均为系列之作。《蜘蛛侠: 英雄远征》的时间线延续“复联 4”,彼得·帕克和全 世界都在适应没有钢铁侠的世界,尚处于青少年的彼得 更是意志消沉,陷入了自己到底是“普通人”还是“英 雄”的自我怀疑中。新人物“神秘客”的加入仿佛给了 彼得更多的希望,但随着故事的层层深入,他身上的谜 团也越来越多。神盾局局长尼克·弗瑞回归领军,他的 真实身份竟然成了故事的最大亮点。“欲带皇冠,必承 其重”,且看新一代蜘蛛侠如何走出困惑,快速成长。 1 主 题 THEME Several of this month's Hollywood blockbusters are After a nine-year wait, the fourth installment of the Toy franchises. The timeline of Spider-Man: Far From Home Story series finally sees the light of day. This Pixar classic, continues on from Avengers: Endgame. -

“Qiulai” Qin Unraveled by Radiocarbon Dating, Chinese Inscriptions And

Durier et al. Herit Sci (2021) 9:89 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-021-00563-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The story of the “Qiulai” qin unraveled by radiocarbon dating, Chinese inscriptions and material characterization Marie‑Gabrielle Durier1,2,3* , Alexandre Girard‑Muscagorry3,4, Christine Hatté1*, Tiphaine Fabris2,5, Cyrille Foasso6, Witold Nowik2,5 and Stéphane Vaiedelich2,3 Abstract An ancient table zither qin, an emblematic stringed instrument of traditional Chinese music, has been rediscovered in the museum collection of the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (inv.4224, CNAM collection), Paris. This instrument named “Qiulai” qin, whose origin is poorly documented, can claim to be one of the oldest qin preserved in European collections; its state of conservation is exceptional. A thorough examination was carried out based on an innovative approach combining museum expertise, material characterization analyses (optical microscopy, VIS/ IR/UV imaging, X-ray fuorescence, SEM–EDS, Raman) and advanced radiocarbon dating technology (MICADAS). Our results highlight the great coherence with the traditional manufacturing practices mentioned in early Qing dynasty qin treatises and poems, in particular the collection of materials with highly symbolic meanings referring to the qin sound, nature and the universe. The reuse of resinous wood of the Taxus family from a building such as a temple has been demonstrated. The ash layer contains bone black, crushed malachite and residues of silica, ochres, potassium and magnesium aluminosilicates. Our study confrms the antiquity of the "Qiulai" qin in Europe by indicating that it was most likely made in the small [1659–1699] interval of about 30 years at the turn of the eighteenth century.