Attachment E Individual and Standard Responses to Public Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY and TRANSPORTATION DEPARTMENT

ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY AND TRANSPORTATION DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE ...................................................................................................4 ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY COMMISSION....................................................5 CONSTRUCTION HIGHLIGHTS ................................................................................6 GROUNDBREAKINGS & RIBBON CUTTINGS ....................................................8 RECOGNITIONS & ACCOMPLISHMENTS ........................................................10 TOP TEN CONTRACTS OF 2012 .........................................................................11 AHTD ORGANIZATION & WORKFORCE ........................................................12 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT ..............................................................................................13 DISTRICT INFORMATION ........................................................................................14 FRONT & BACK COVER PHOTOS: Construction at Big Rock AHTD MISSION To provide a safe, efficient, aesthetically pleasing and environmentally Interstate 430/630 Interchange sound intermodal transportation system for the user. Little Rock, Arkansas • July 2012 STATEMENT Photography by John Jackson 2012 HIGHWAY COMMISSION CHAIRMAN R. MADISON MURPHY of El Dorado, was appointed DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE by Governor Mike Huckabee effective January 14, 2003. He began work as a Junior Accountant COMMISSION for Murphy Oil in 1980 and moved up to Junior Auditor and Associate -

Final Report

FINAL REPORT December 1, 2010 Presented to: The Honorable Mike Beebe, Governor House Interim Committee on Public Transportation Senate Interim Committee on Transportation, Technology and Legislative Affairs House Interim Committee on Revenue and Taxation Senate Interim Committee on Revenue and Taxation Arkansas Legislative Council Arkansas State Highway Commission Association of Arkansas Counties Arkansas Municipal League TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairman’s Comments and Summary of Recommendations .............................. i Introduction.............................................................................................................. 1 Highway Needs – Historic Information .................................................................. 3 Highway Revenue – A Structural Problem ............................................................ 6 The Link Between Transportation Investments and the Economy.................... 15 Revenue Proposals ............................................................................................... 17 Other Recommended Legislation......................................................................... 28 Recommended Studies......................................................................................... 31 Other Recommendations...................................................................................... 34 Appendix................................................................................................................ 35 CHAIRMAN’S COMMENTS AND SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS -

2016 ANNUAL Report

2016 ANNUAL Report ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY AND TRANSPORTATION DEPARTMENT AHTD Mission Statement To provide a safe, efficient, aesthetically pleasing and environmentally sound intermodal transportation TABLE OF system for the user. CONTENTS 4 DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE 6 ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY COMMISSION 8 TOP TEN CONTRACTS OF 2016 10 CONSTRUCTION HIGHLIGHTS 14 IMPROVING OUR HIGHWAY SYSTEM 16 GROUNDBREAKINGS & RIBBON CUTTINGS 18 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT 19 IDRIVEARKANSAS AND TWITTER STATISTICS 20 RECOGNITIONS & ACCOMPLISHMENTS 22 DISTRICT INFORMATION PHOTO THIS PAGE / Highway 70 Railroad Overpass (Roosevelt Rd., Little Rock) photo by Rusty Hubbard 24 ORGANIZATION & WORKFORCE FRONT & BACK COVER PHOTOS / Highway 70 Bridge (Broadway St.) over the Arkansas River photo by Rusty Hubbard 2 3 WORK CONTINUED ON REPLACING the Broadway Bridge (U.S. HIGHWAY 70) CONNECTING Little Rock and DIRECTOR’S message North Little Rock HE ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY AND TRANSPORTATION DEPARTMENT (AHTD) is proud to present our annual report and share the highlights and successes that the Department experienced over calendar year 2016. For the year, the Department let to contract 263 projects totaling just overT $1.2 billion. The largest of those projects was on Interstate 40 in Prairie County. In addition, work continued on replacing the Broadway Bridge (U.S. Highway 70) connecting Little Rock and North Little Rock and on improvements to Interstates 49 and 440. This report provides information on projects in all 10 of our Districts across the State. Each reflects our commitment to making our highway system one of the best in the nation as well as one of the safest. Our two major road improvement programs progressed well in 2016. -

Annual Report

ALABAMA ARKANSAS FLORIDA GEORGIA KENTUCKY LOUISIANA MISSISSIPPI NORTH CAROLINA PUERTO RICO SOUTH CAROLINA TENNESSEE VIRGINIA WEST VIRGINIA ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ALABAMA ARKANSAS FLORIDA GEORGIA KENTUCKY LOUISIANA MISSISSIPPI NORTH CAROLINA PUERTO RICO SOUTH CAROLINA TENNESSEE VIRGINIA WEST VIRGINIA contents letter page from our 2014 host state Who is SASHTO? LOUISIANA 3 4 Policy and Legislative Agenda t has been a wonderful privilege to serve as President of such a fine ALABAMA — Heart of Dixie organization and to host the 2014 annual meeting in beautiful New Orleans. 5 Transportation is vitally important to the economy and quality of life for the 7 ARKANSAS — The Natural State nation and for the SASHTO region. Our dynamic global economy demands the ability to quickly and reliably move information, people and goods. 9 FLORIDA — Sunshine State In many respects, transportation has never seen so many challenges and yet so many opportunities as well. 11 GEORGIA — State of Adventure Change has been a constant and it is probably accurate to say that change will only 13 KENTUCKY — Bluegrass State Iaccelerate, making it ever more essential for SASHTO states to adapt and innovate individually and corporately. Each state has extensive transportation needs, and relies on 15 LOUISIANA — Sportsman’s Paradise Sherri H. LeBas a program of federal-aid for highways, bridges and transit. Clearly, as much as we rely on and need a significant federal investment, our states are perhaps being called to a level of 17 MISSISSIPPI — The Birthplace of America’s Music unprecedented leadership in transportation finance and other areas as well. Transportation system performance in each state and for our entire region requires us to embrace the 19 NORTH CAROLINA — First in Flight “can-do” value that is so emblematic of SASHTO. -

AGENDA Governor's Working Group on Highway Funding

AGENDA Governor’s Working Group on Highway Funding Thursday, September 3, 2015 1:30 PM Room 151, State Capitol Little Rock, Arkansas Duncan Baird, Chair Philip Taldo Scott Bennett Dr. Brett Powell Alec Farmer Larry Walther Rep. Dan Douglas Guy Washburn Sen. Bill Sample Shannon Newton Rep. Andy Davis Charles Weaver Rep. Prissy Hickerson Craig Douglass County Judge Jerry Holmes Jackson Williams Mayor Harold Perrin Frank Scott, Jr Randy Zook Dr. Robin Bowen A. Call to Order Duncan Baird, Chair B. Follow-up Discussion from Last Meeting a. AHTD Detailed Spending Plan Scott Bennett, Director, AHTD b. Arkansas’ Underground Storage Tank (UST) Programs Joe Hoover, Chief, Regulated Storage Tanks Division, ADEQ c. State Central Services Fund C. Examination of Other State’s Actions a. Georgia, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah Duncan Baird, DF&A D. Discussion and Determination of Short-Term Funding Options for Arkansas E. Closing Remarks Governor’s Working Group on Highway Funding Minutes of August 20, 2015 Meeting Arkansas State Capitol Room 149 1:30 p.m. Action items are highlighted in yellow and also summarized at the end of this document. In Attendance: Duncan Baird, Chair Rep. Prissy Hickerson Guy Washburn Scott Bennett Judge Jerry Holmes Shannon Newton Alec Farmer Randy Zook Craig Douglass Rep. Dan Douglas Philip Taldo Jackson Williams Sen. Bill Sample Dr. Brett Powell Frank Scott, Jr. Rep. Andy Davis Larry Walther Agenda Item A – Call to Order Duncan Baird, Chairman, called the meeting to order. Arkansas Highway Commissioner Frank Scott, Jr. recognized former Highway Commissioner and former U.S. Secretary of Transportation, Rodney Slater, who was in attendance at the meeting. -

Executive Summary Director’S Letter July 2017

ARKANSAS Long Range Intermodal Transportation Plan Executive Summary Director’s Letter July 2017 Greetings! Every day, Arkansans rely on our transportation system to get to work, to school, to go shopping, and visit our beautiful lakes and mountains. Our local businesses use this same system to move products to local, regional and global markets. A healthy intermodal transportation system is the backbone of a modern, competitive, and productive economy that connects highways, rail, waterways, and air transport making the movement of people and goods more efficient, supporting trade and commerce, connecting supply chains, and reducing operating costs for everyone. Over the past 18 months, our staff updated the Statewide Long Range Intermodal Transportation Plan to create a performance-based blueprint for the future of transportation in Arkansas. Thousands of citizens were involved in the development of the Plan goal, objectives, and implementation strategies. The Plan examines all aspects of the Arkansas' intermodal transportation system including highways, bridges, public transportation, rail, bicycle, pedestrian, ports and waterways, and aviation. Tough issues were addressed – such as a growing and aging population and the expected growth in travel and freight shipments over the next 25 years. More and more, individuals and businesses want reliability in their travel options whether it is knowing how long a trip will take or if they can deliver their cargo on time. At the same time, our staff also updated the Department's Strategic Plan identifying our mission, vision, core values and strategic goals related to providing the best transportation system for Arkansas. With the completion of these two Plans, we have collectively identified policies and strategies that will assist in moving Arkansas' transportation system forward to meet the 21st century challenges. -

Recommendations of the Work Group for the Consideration of the Blue Ribbon Committee on Highway Finance Recommendations Overview

Recommendations of the Work Group for the Consideration of The Blue Ribbon Committee on Highway Finance Recommendations Overview The Work Group considered those items brought forward by the two Subcommittees and by unanimous consent added Reissuance of the GARVEE Bonds for Interstate Reconstruction. This report is broken into four sections: Revenue Proposals, Recommended Studies, Recommended Legislation and Other Recommendations. For each item in each section, the proposal is stated briefly, followed by a rationale. Work Group Action on that proposal is noted next. Where there was unanimous agreement on the proposal, it is noted. Where there was not, the majority opinion of the Work Group is noted followed by the issues that the full committee may wish to debate and decide. For revenue items, revenue projections are made with assumptions clearly stated. Background information, if available, is included for the members’ information. Overarching Assumptions For all revenue projections, unless otherwise noted, it is assumed that 70% of net revenues will go to AHTD, 15% to the counties and 15% to the cities. All revenue projections are made assuming a 1.7% annual VMT growth over the coming decade, increased average fleet fuel efficiency of 2.8% per year over the same period, and gasoline and diesel prices based on the Moody’s Econometrics projections. ‐ 1 ‐ Revenue Proposals 1. Index the Gas and Diesel Excise Tax Proposal: Index the existing gas and diesel excise taxes to the Construction Cost Index three‐year trailing average using 2010 as the base year. The indexing should be an annual and automatic administrative function of the Department of Finance and Administration conducted as soon as practicable after the end of the fiscal year or calendar year, whichever is most advantageous. -

The Economic Impacts of an Annual $478 Million Increase in Arkansas Highway, Street and Bridge Construction Investment

The Economic Impacts of an Annual $478 Million Increase in Arkansas Highway, Street and Bridge Construction Investment OCTOBER 2018 This research was conducted for the Associated General Contractors of Arkansas (AGC Arkansas) by the economics & research team at the Washington, D.C.-based American Road & Transportation Builders Association (ARTBA). This analysis was led by Dr. Alison Premo Black, ARTBA’s senior vice president and chief economist. Research Economist Lital Shair Nada and Transportation Investment Advocacy Center Director Carolyn Kramer made significant contributions to this study. Since joining ARTBA in 2000, Dr. Black has led teams and authored nearly 100 studies examining state transportation funding and investment patterns. Dr. Black also leads the operation of the Transportation Investment Advocacy Center ™. She has a Ph.D. in economics from the George Washington University and a master’s in international economics and Latin American Studies from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. Ms. Nada has a master’s of science in applied economics degree from the Johns Hopkins University. She graduated magna cum laude from Brandeis University with degrees in economics and international & global studies. Since joining ARTBA in 2012, Ms. Nada has authored over 25 custom reports for clients. She also manages ARTBA’s transportation market intelligence subscription reports, is director of the association’s Transportation Officials Division, and is assistant director of the association’s Research & Education Division. Ms. Kramer tracks and analyzes recent state transportation funding legislative and ballot initiatives, as well as reports on methods and trends. She also organizes the annual National Workshop for State & Local Transportation Advocates and manages the Transportation Investment Advocacy Council, a national network of advocates who share a common interesting in increasing state and local transportation investment. -

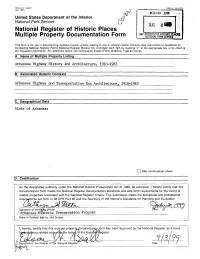

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NFS Form 10-900-b OMB No. W24-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service D MJS 4 National Register of Historic Places NAT. REGISTER OF HISTORI Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL PARK This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_________________________________________ Arkansas Highway History and Architecture, 1910-1965__________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Arkansas Highway and Transportation Era Architecture, 1910-1965____________ C. Geographical Data State of Arkansas I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifxMg official Arkansas Historic Preservation Program State or Federal agency and bureau hereby, certify that this multiple propert orm has been approved by the National Register as a basis related proe/fi^s/for listi egister. •"Va^V^^^ V*———— ^*T1 lL__ J-^—————~^—————*—————'——-—————"—' I ^| Signature of the Keeper of tne National Register Date NPSForm10-900-a " ,, OMB Approval No. -

Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department

Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department Regional Logistics Council Meeting Memphis Chamber of Commerce Thursday, April 16, 2015 Regional Briefing – Arkansas Lorie H. Tudor, P.E. Deputy Director and Chief Operating Officer Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department Regional Logistics Council Memphis, TN April 16, 2015 2011 2012 Program Interstate Rehabilitation Scheduled Under Construction Complete Hwy. 77 to I-55 Reconstruction 2 miles Shearerville – Hwy. 77 Resurfacing 12.9 miles Blackfish Lake Bridge Reconstruction Shell Lake Bridge Reconstruction Fishing Lake Bridge Reconstruction Shearerville – West Pavement Improvement 16.5 miles IRP Projects Program Arkansas Connecting 35 Scheduled 3 Under Const. 0 Complete Co. Rd. 375-Hwy. 147 (Widening) (S) 5.5 miles Cross Co. Line-Co. Rd. 375 (Widening) (S) 8.3 miles • Canada to Mexico • 2,730 miles • Estimated Cost to Complete - $30 Billion • Congressionally Designated High Priority Corridors 18 & 20 • Includes the I-69 Connector I-69 Connector Funding Summary Status Miles Total Complete 22.5 $140 million Under 6.5 $35 million Construction Scheduled 2.8 $14 million Unfunded 10.5 $520 million Totals 42.3 $709 million Future Future Interstate 69 Interstate 69 Montello Bypass Groundbreaking November 9, 2011 Monticello Bypass 11:00 a.m. Groundbreaking November 9, 2011 Monticello Bypass 11:00 a.m. I-69 Great River Bridge • Design Complete • Estimated Cost - $1.3 Billion – Arkansas’ Portion - $910 Million • ROW Acquisition Underway Future Interstate 555 Projects Withdrawn from Bid Openings in 2015 Impacts to Arkansas 2015 61 Projects Removed $162 million POTENTIAL RISK FFY 2015 120 Projects $490 Million FFY 2016 130 Projects $520 Million Project Goals - Determine feasibility of using tolls to finance the widening of Interstate 40 from four to six lanes between North Little Rock and West Memphis, a distance of 110 miles. -

Senator Bill Sample Talks Transportation

MARCH/APRIL 2017 A PUBLICATION OF THE ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY & TRANSPORTATION DEPARTMENT Senator Bill Sample Talks Transportation Commissioner DIGGING IN A NEW FRANK SCOTT THE DIRT TO Striping Strategy Bids Farewell Preserve the Past for Highways FRONT COVER: DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE Senator Bill Sample on the steps ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY of the CapitolBACK COVER:in Little Rock. COMMISSION in Little Rock. The Challenge Remains the Same The State Capitol building PUBLISHER HE DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE IN THE INSET APPEARED IN THE SPRING Danny Straessle 1980 ISSUE OF ARKANSAS HIGHWAYS MAGAZINE. THE THOUGHTFUL [email protected] DICK TRAMMEL Chairman WORDS WERE WRITTEN BY THEN DIRECTOR HENRY GRAY. EDITOR T David Nilles [email protected] in print today, 37 years later. Reading Gray’s message, it may remind you, ironically, of something you might find GRAPHIC DESIGNER We’ve experienced many noteworthy improvements in the transportation industry Paula Cigainero since that letter was written. Longer lasting pavements, Intelligent Transportation [email protected] CONTRIBUTING WRITERS for surveying and virtual weigh stations are just a few advances that have improved Matt Barnette Systems (ITS), high friction surface treatments, video traffic modeling, total stations our highway system. [email protected] Glenn Bolick THOMAS B. SCHUECK However, the more things change, the more they stay the same. The one thing that has remained constant over the Vice Chairman [email protected] years has been the need for additional revenue. Unfortunately, we aren’t able to raise revenue ourselves. For that, we rely PHOTOGRAPHER Rusty Hubbard onWhat our elected we are officials able to do both is the at homebest and in Washington, D.C. -

Statewide Long Range Intermodal Transportation Plan

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................... vii 1. Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 1.1 State and Federal Legislation and Requirements ........................................... 1 1.2 Background ....................................................................................... 3 1.3 ARDOT’s Responsibilities and Partners ....................................................... 4 1.4 Organization of the Long-Range Intermodal Transportation Plan ........................ 5 2. Public and Stakeholder Outreach .................................................................. 7 2.1 Stakeholder Interviews ......................................................................... 7 2.2 Project Website ................................................................................. 8 2.3 Scenario Planning Workshop ................................................................... 8 2.4 Transportation Planning Advisory Group ..................................................... 9 2.5 Public Meetings ................................................................................. 10 2.5.1 Comment Form Summary ............................................................. 11 2.5.2 Reaction to Goals ...................................................................... 11 2.5.3 Transportation Priorities ............................................................. 11 2.6 Internal ARDOT Input