Kilmarnock - a Historical Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

1 bus time schedule & line map 1 Priestland - Kilmarnock View In Website Mode The 1 bus line (Priestland - Kilmarnock) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kilmarnock: 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM (2) Priestland: 4:51 AM - 10:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 1 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 1 bus arriving. Direction: Kilmarnock 1 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Kilmarnock Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Loudon Avenue, Priestland Loudoun Avenue, Scotland Tuesday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM John Morton Crescent, Darvel Wednesday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM McIlroy Court, Scotland Thursday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Murdoch Road, Darvel Friday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Murdoch Road, Darvel Saturday 5:23 AM - 10:30 PM Green Street, Darvel Temple Street, Darvel Hastings Square, Darvel 1 bus Info Fleming Street, Darvel Direction: Kilmarnock Stops: 29 Fleming Street , Darvel Trip Duration: 33 min Line Summary: Loudon Avenue, Priestland, John Dublin Road, Darvel Morton Crescent, Darvel, Murdoch Road, Darvel, Dublin Road, Scotland Green Street, Darvel, Temple Street, Darvel, Fleming Street, Darvel, Fleming Street , Darvel, Dublin Road, Alstonpapple Road, Newmilns Darvel, Alstonpapple Road, Newmilns, Union Street, Newmilns, East Strand, Newmilns, Castle Street, Union Street, Newmilns Newmilns, Baldies Brae, Newmilns, Queens Crescent, Isles Street, Scotland Greenholm, Mure Place, Greenholm, Gilfoot, Greenholm, Barrmill Road, Galston, Church Lane, East Strand, Newmilns Galston, Boyd -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran & Cumbrae

2017-18 EXPLORE ayrshire & the isles of arran & cumbrae visitscotland.com WELCOME TO ayrshire & the isles of arran and cumbrae 1 Welcome to… Contents 2 Ayrshire and ayrshire island treasures & the isles of 4 Rich history 6 Outdoor wonders arran & 8 Cultural hotspots 10 Great days out cumbrae 12 Local flavours 14 Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology 2017 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 VisitScotland iCentres 21 Quality assurance 22 Practical information 24 Places to visit listings 48 Display adverts 32 Leisure activities listings 36 Shopping listings Lochranza Castle, Isle of Arran 55 Display adverts 37 Food & drink listings Step into Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran and Cumbrae and you will take a 56 Display adverts magical ride into a region with all things that make Scotland so special. 40 Tours listings History springs to life round every corner, ancient castles cling to spectacular cliffs, and the rugged islands of Arran and Cumbrae 41 Transport listings promise unforgettable adventure. Tee off 57 Display adverts on some of the most renowned courses 41 Family fun listings in the world, sample delicious local food 42 Accommodation listings and drink, and don’t miss out on throwing 59 Display adverts yourself into our many exciting festivals. Events & festivals This is the birthplace of one of the world’s 58 Display adverts most beloved poets, Robert Burns. Come and breathe the same air, and walk over 64 Regional map the same glorious landscapes that inspired his beautiful poetry. What’s more, in 2017 we are celebrating our Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology, making this the perfect time to come and get a real feel for the characters, events, and traditions that Cover: Culzean Castle & Country Park, made this land so remarkable. -

Kirkoswald, Maidens and Turnberry Community Action Plan 2019-2024 &RQWHQWV

Funded by Scottish Power Renewables Kirkoswald, Maidens and Turnberry Community Action Plan 2019-2024 &RQWHQWV What is a Community Action Plan?............................................................................1 Why a Community Action Plan?.................................................................................2 Introducing Kirkoswald, Maidens and Turnberry………….........................................................................................................3 Our Process........................................................................................................................4 Consultation……………………………...................................................................5 Kirkoswald, Maidens and Turnberry’s Voices: Drop-in Sessions…………………………................................................................................6 Kirkoswald, Maidens and Turnberry’s Voices: Schools and Young People................................................................................................................................. 7 The Headlines 2024.........................................................................................................9 The Vision..........................................................................................................................11 Priorities.....................................................................................................................12 Actions...............................................................................................................................13 -

East Ayrshire Local Development Plan Non-Statutory Planning Guidance

East Ayrshire Council East Ayrshire Local Development Plan Non-statutory Planning Guidance Bank Street and John Finnie Street Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan 2007 Austin-Smith:Lord LLP East Ayrshire Council 5th December 2007 Kilmarnock John Finnie Street and Page 1 of 135 207068 Bank Street Conservation Area Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Statutory Designations 3.0 Planning and Other Policies 4.0 History and Context 5.0 Architectural Appraisal 6.0 Townscape and Urban Realm Appraisal 7.0 Archaeological Assessment 8.0 Assessment of Significance 9.0 Vulnerability and Related issues 10.0 Conservation and Management Guidelines 11.0 Implementation and Review APPENDICES Appendix One - Outstanding Conservation Area Boundaries and Properties Appendix Two - Statutory Designations Appendix Three - Buildings Gazetteer Appendix Four - Archaeological Gazetteer Appendix Five - Definitions Austin-Smith: Lord LLP 296 St. Vincent Street, Glasgow. G2 5RU t. 0141 223 8500 f. 0141 223 8501 e: [email protected] June 2007 Austin-Smith:Lord LLP is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC315362. Austin-Smith:Lord LLP East Ayrshire Council 5th December 2007 Kilmarnock John Finnie Street and Page 2 of 135 207068 Bank Street Conservation Area Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan Austin-Smith:Lord LLP East Ayrshire Council 5th December 2007 Kilmarnock John Finnie Street and Page 3 of 135 207068 Bank Street Conservation Area Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan 1.0 INTRODUCTION th Figure 1: John Finnie Street from Station Brae and the North, Early 20 Century (author’s collection) 1.1 The character of Kilmarnock is shaped by the quality and diversity of its historic buildings and streetscape. -

Thecommunityplan

EAST AYRSHIRE the community plan planning together working together achieving together Contents Introduction 3 Our Vision 3 Our Guiding Principles 4 The Challenges 8 Our Main Themes 13 Promoting Community Learning 14 Improving Opportunities 16 Improving Community Safety 18 Improving Health 20 Eliminating Poverty 22 Improving the Environment 24 Making the Vision a Reality 26 Our Plans for the next 12 years 28 Our Aspirations 28 2 Introduction Community planning is about a range of partners in the public and voluntary sectors working together to better plan, resource and deliver quality services that meet the needs of people who live and work in East Ayrshire. Community planning puts local people at the heart of delivering services. It is not just about creating a plan or a vision but about jointly tackling major issues such as health, transport, employment, housing, education and community safety. These issues need a shared response from, and the full involvement of, not only public sector agencies but also local businesses, voluntary organisations and especially local people. The community planning partners in East Ayrshire are committed to working together to make a real difference to the lives of all people in the area. We have already achieved a lot through joint working, but we still need to do a lot more to make sure that everybody has a good quality of life. Together, those who deliver services and those who live in our communities will build on our early success and on existing partnerships and strategies to create a shared understanding of the future for East Ayrshire. -

Redirecting to East Ayrshire Council

EAST AYRSHIRE COUNCIL CABINET REPORT – 3RD OCTOBER 2007 ADDITIONAL STREETSPORT CAGES Report by Executive Director of Neighbourhood Services 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT 1.1 To request that the Cabinet approve the installation of two new StreetSport Cages in Crosshouse and Newmilns, and agree the proposed site for the similar facility in Darvel subject to the satisfactory outcome of consultation exercises. 2. BACKGROUND 2.1 Following the success of existing Multi-use Games Areas in Shortlees and North West Kilmarnock, Leisure Services have worked in partnership with East Ayrshire Sports Council to develop a network of these facilities across East Ayrshire. These new facilities now known as StreetSport Cages, compliment and extend the range of play facilities being made available through the Council’s Playpark Improvement Programme. 2.2 Further to Committee approval at Community Services Committee on 8th November 2006, a network of facilities was developed via a range of external and internal funding allocations. The development and subsequent installation of this network demonstrated East Ayrshire’s forward thinking approach to the development of Community Sport and its commitment to providing young people with positive alternatives to Youth Crime. This was highlighted nationally with the Council being featured on BBC Radio Scotland’s Good Morning Scotland Show and on BBC TV’s Reporting Scotland. 2.3 A subsequent report to Community Services Committee on 31st January 2007 approved the allocation of an additional StreetSport Cage to Darvel. Final implementation, however, was to be subject to a community consultation process. 2.4 The original proposal for the Darvel StreetSport Cage was to site it within the boundaries of Morton Park as the majority of youth disorder complaints being received from Darvel focused on this area. -

Polling Scheme

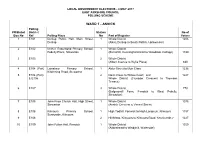

LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS - 4 MAY 2017 EAST AYRSHIRE COUNCIL POLLING SCHEME WARD 1 - ANNICK Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 1 E101 Dunlop Public Hall, Main Street, 1 Whole District 1286 Dunlop (Aiket, Dunlop to South Pollick, Uplawmoor) 2 E102 Nether Robertland Primary School, 1 Whole District Pokelly Place, Stewarton (Barnahill, Cunninghamhead to Woodside Cottage) 1199 3 E103 2 Whole District (Albert Avenue to Wylie Place) 830 4 E104 (Part) Lainshaw Primary School, 1 Alder Street to Muir Close 1236 Kilwinning Road, Stewarton 5 E104 (Part) 2 Nairn Close to Willow Court; and 1227 & E106 Whole District (Crusader Crescent to Thomson Terrace) 6 E107 3 Whole District 770 (Balgraymill Farm, Fenwick to West Pokelly, Stewarton) 7 E105 John Knox Church Hall, High Street, 1 Whole District 1075 Stewarton (Annick Crescent to Vennel Street) 8 E108 Kilmaurs Primary School, 1 High Todhill, Fenwick to High Langmuir, Kilmaurs 1157 Sunnyside, Kilmaurs 9 E108 2 Hill Moss, Kilmaurs to Kilmaurs Road, Knockentiber 1227 10 E109 John Fulton Hall, Fenwick 1 Whole District 1350 (Aitkenhead to Windyhill, Waterside) 2 WARD 2 - KILMARNOCK NORTH Polling PO/Ballot District Station No of Box No Ref Polling Place No Part of Register Voters 11 E201 (Part) St John’s Parish Church Main Hall, 1 Altonhill Farm to Newmilns Gardens 1046 Wardneuk Drive, Kilmarnock 12 E201 (Part) 2 North Craig, Kilmarnock to Grassmillside, Kilmaurs 1029 13 E202 3 Whole District 1094 (Ailsa Place to Toponthank Lane) 14 E203 (Part) Hillhead -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The City of Edinburgh Council

Notice of meeting and agenda The City of Edinburgh Council 10.00 am, Thursday, 15 December 2016 Council Chamber, City Chambers, High Street, Edinburgh This is a public meeting and members of the public are welcome to attend Contact E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 0131 529 4246 1. Order of business 1.1 Including any notices of motion and any other items of business submitted as urgent for consideration at the meeting. 2. Declaration of interests 2.1 Members should declare any financial and non-financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 3. Deputations 3.1 If any 4. Minutes 4.1 The City of Edinburgh Council of 24 November 2016 (circulated) – submitted for approval as a correct record 5. Questions 5.1 By Councillor Bagshaw - Key Junctions on Princes Street – for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.2 By Councillor Booth – Council Support for Small and Medium Sized Shops – for answer by the Convener of the Economy Committee 5.3 By Councillor Booth – Forth Ports - for answer by the Convener of the Economy Committee 5.4 By Councillor Booth – Low Emission or Clean Air Zones - for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.5 By Councillor Booth – Air Quality Management Area - for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.6 By Councillor Burgess – Long Term Empty Homes – for answer by the Convener of the Health, Social Care and Housing Committee 5.7 By -

Ayrshire, Its History and Historic Families

suss ^1 HhIh Swam HSmoMBmhR Ksaessaa BMH HUB National Library of Scotland mini "B000052234* AYRSHIRE BY THE SAME AUTHOR The Kings of Carrick. A Historical Romance of the Kennedys of Ayrshire - - - - - - 5/- Historical Tales and Legends of Ayrshire - - 5/- The Lords of Cunningham. A Historical Romance of the Blood Feud of Eglinton and Glencairn - - 5/- Auld Ayr. A Study in Disappearing Men and Manners -------- Net 3/6 The Dule Tree of Cassillis - Net 3/6 Historic Ayrshire. A Collection of Historical Works treating of the County of Ayr. Two Volumes - Net 20/- Old Ayrshire Days - - - - - - Net 4/6 X AYRSHIRE Its History and Historic Families BY WILLIAM ROBERTSON VOLUME I Kilmarnock Dunlop & Drennan, "Standard" Office Ayr Stephen & Pollock 1908 CONTENTS OF VOLUME I PAGE Introduction - - i I. Early Ayrshire 3 II. In the Days of the Monasteries - 29 III. The Norse Vikings and the Battle of Largs - 45 IV. Sir William Wallace - - -57 V. Robert the Bruce ... 78 VI. Centuries on the Anvil - - - 109 VII. The Ayrshire Vendetta - - - 131 VIII. The Ayrshire Vendetta - 159 IX. The First Reformation - - - 196 X. From First Reformation to Restor- ation 218 XI. From Restoration to Highland Host 256 XII. From Highland Host to Revolution 274 XIII. Social March of the Shire—Three Hundred Years Ago - - - 300 XIV. Social March of the Shire—A Century Back 311 XV. Social March of the Shire—The Coming of the Locomotive Engine 352 XVI. The Secession in the County - - 371 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/ayrshireitshisv11908robe INTRODUCTION A work that purports to be historical may well be left to speak for itself. -

Catrine's Other Churches

OTHER CHURCHES IN CATRINE THE UNITED SECESSION CHURCH (Later: The United Presbyterian Church) he 1891 Census states that in its early days the population of Catrine “…contained a goodly sprinkling of Dissenters…some of whom travelled to Cumnock to the TWhig Kirk at Rigg, near Auchinleck; but a much larger number went to the Secession Church at Mauchline. The saintly Mr Walker, minister there, becoming frail and not able to attend to all his flock, this (ie.1835) was thought to be a suitable time to take steps to have a church in Catrine”. An application for a site near the centre of the village was made to the Catrine Cotton Works Company, but this was refused by the then resident proprietor who said that: “He could not favour dissent.” A meeting of subscribers was held on 16th June 1835 when it was decided to approach Mr Claud Alexander of Ballochmyle with a request for ground. Mr Alexander duly granted them a site at the nominal sum of sixpence per fall. (A fall was equal to one square perch – about 30.25 square yards.) Another meeting of subscribers on 12th April 1836 authorised obtaining a loan of up to £350 to cover the cost of erecting a building on the site at the foot of Cowan Brae (i.e. at the corner where the present day Mauchline Road joins Ballochmyle Street). James Ingram of St.Germain Street, father of the eminent architect Robert Samson Ingram of Kilmarnock, was appointed to draw out plans. A proposal was approved to place a bottle containing the County newspaper in the foundation.