Britain After Coronavirus: Birmingham and How We Recovered And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Council House, Victoria Square, Birmingham, B1 1BB Listed

Committee Date: 27/06/2013 Application Number: 2013/01613/PA Accepted: 16/04/2013 Application Type: Listed Building Target Date: 11/06/2013 Ward: Ladywood The Council House, Victoria Square, Birmingham, B1 1BB Listed Building Consent for the installation of 4 no. internal recording cameras to Committee Rooms 3 & 4. Applicant: Acivico - Birmingham City Council The Council House, Victoria Square, Birmingham, B1 1BB Agent: Acivico - Development Dept 1 Lancaster Circus, Queensway, Birmingham, B2 2WT Recommendation Refer To The Dclg 1. Proposal 1.1. This application seeks Listed Building Consent for the installation of 4 no. internal recording cameras at The Council House in Victoria Square. 1.2. The cameras would be 0.14m (w) x 0.16m (h) x 0.16m (d) to be installed in each corner of Committee Rooms 3 and 4 used to record meetings. They would be coloured white. 2. Site & Surroundings 2.1. The Birmingham Council House occupies a site between Chamberlain Square, Eden Place, Victoria Square and Chamberlain Square. The present building was designed by Yeoville Thomason and built between 1874 and 1879 on what was once Ann Street. 2.2. The building is three storeys plus basement made of stone with a tile roof. The site forms part of the Colmore Row and Environs Conservation Area designated in October 1971 and extended in March and then July 1985. 2.3. The building provides office accommodation for both employed council officers, Chief Executive and elected council members. There is also a large and ornate banqueting suite complete with minstrels gallery. Committee Rooms 3 & 4 are located on the ground floor fronting onto Victoria Square. -

Travelling to UCE Birmingham Conservatoire

Travelling to UCE Birmingham Conservatoire ROAD From M6 South or North-West Leave the M6 at Junction 6 and follow the A38(M). Follow signs to ‘City centre, Bromsgrove, (A38)’. Do not take any left exit. Go over 1 flyover and through just 1 Queensway tunnel (sign posted ‘Bromsgrove and Queen Elizabeth Hospital’). Leave this tunnel indicating left but stay in the right hand lane of the slip road. UCE Birmingham Conservatoire is located on the Paradise Circus island. Follow directions below for parking and/or loading & unloading. Parking Car parking at the Conservatoire is very limited and we regret we cannot offer parking spaces to visitors. However, there are several NCP car parks located close by, including two located on Cambridge Street. To access these car parks, at the Paradise Circus island, immediately after you pass the exit for the A456 (Broad Street), move into the left lane and take the first left into Cambridge Street. Loading & Unloading To access the Conservatoire’s car park (for loading and unloading only), pass under the bridge and turn right as if to access the Copthorne Hotel, and then right again into the underground road. Follow the road around to the left to gain access to the Conservatoire’s car park, which is at the end of the road. A goods lift is available. From M5 South-West Leave the M5 at Junction 3 and travel towards Birmingham City Centre along the A456 (Hagley Road) for 5 miles to the Five Ways island. This is easily distinguishable as it is surrounded by large office blocks and a Tesco store. -

Octagon-Proposal-07-2020.Pdf

CITY LIVING RESHAPED Octagon is not just a first for Birmingham, but will be unique in the UK and beyond. Offering a mix of 346 spacious new Build to Rent (BtR) homes designed to excel in every way, we want to build the first pure residential octagonal high rise building in the world. CONTENTS Introduction 03 Planning History 06 Site Location 12 Octagon 16 Key Facts 22 The Architecture 24 Internal Design 28 One Bedroom Home 34 Two Bedroom Home 35 Three Bedroom Home 36 Ground Floor Uses 38 The Central Core & Cladding 42 Market Demand 44 Delivering Octagon 46 The Architects 48 INTRODUCING RESIDENTIAL TO PARADISE Following the Octagon online public consultation process held from 5 – 26th May 2020, we are now processing the many comments we received which will help inform the planning application we submit to Birmingham City Council this summer. If Birmingham City Council subsequently approves our plans, the hope will be for work on Octagon to begin during 2021 and complete in 2024. 02 / Octagon Birmingham 03 Outline planning permission was We are working as part of a public Paradise is the £700 million obtained back in 2013 and detailed private sector Joint Venture (JV) with transformation at the very heart applications are now being progressed Birmingham City Council, the LEP and on a phase by phase basis. Federated Hermes, a global investment management company, to bring of Birmingham attracting new The company managing the development forward up to 2 million sq ft of new at Paradise is Argent, who originally development in the heart of the city. -

TPWM News: Project Updates

Artists’ News & Opportunities Bulletin Issue 43: 14 June 2012 Click on the headings below to go straight to your preferred section of the bulletin... o Funding o Opportunities o Commissions o Calls for work o Prizes o Residencies o Traineeships o Jobs o Voluntary Positions o Festivals o Courses/ workshops o Graduate Exhibitions o What’s happening o Ongoing exhibitions TPWM News: Project Updates Artist Development In summer 2012 a professional development programme for artists will be launched by TPWM in collaboration with The Art Gallery Walsall and other partners. It will take place across the West Midlands and will be aimed at artists at varying levels of career development. Details will be available soon on www.tpwestmidlands.org.uk New Art West Midlands 2013: Call for Applications from recent Visual Arts Graduates Application forms available from: http://www.tpwestmidlands.org.uk/new-art-west-midlands-2013/ Deadline: 14 September 2012. Residencies Four organisations in the West Midlands will lead on TPWM new artist residency opportunities: The Library of Birmingham, University of Worcester with Movement Gallery and Worcester City Museum, Eastside Projects and The National Trust at Dudmaston. Two of the four residencies will have an open submission application process. More details will be available soon on www.tpwestmidlands.org.uk Writing Bursary TPWM has awarded a writing bursary to Grand Union (in association with Eastside Projects), in order to offer an opportunity for a new or emerging writer to develop skills in critical writing for publication and encourage writing practice within the West Midlands. The writing bursary will be awarded following an open submission. -

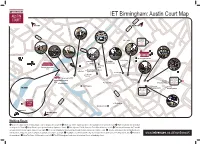

IET Birmingham: Austin Court Map

IET Birmingham: Austin Court Map GRAHAM ST A4400 S A41/M5 M6/M1/M42 U NEWHALL ST M M CAMDEN ST NEW HALL HILL E R H A38 IL L R O A D S UM A457M ER H ILL RD Birmingham Snow Hill CHARLOTTE ST BT Tower Driving Distance SAND PITS 4 mins Walking Distance SAND PITS 15 mins PARADE GREAT CHARLES STREET QUEENSWAY NEWHALL ST A457 LIONEL ST COLMORE ROW ST MARKS CRESCENT Birmingham Cathedral Art Gallery 694m Baskerville Birmingham House Central Library H Council T S Copthorne T House N National Indoor Arena 10 E Hotel C IN 273m T. V 12 New Birmingham Library S C AM 11T BRIIDGE S The Rep (opens Sept 2013) CORPORATION ST Town Hall 6 8 P Centenary A PINFOLD ST NEW ST R 5 9 A 7 Square D I Y SE WA C S Birmingham Symphony Hall/ICC I N HILL ST RC EE U QU HE Moor Street S STEP NSON National Sea Life Centre ST 3 2 Pavillion Driving Distance 342m 4 5 mins Crowne Plaza Shopping Centre Walking Distance Brindleyplace 25 mins BROAD ST H Hyatt Regency 1 Pallasades ST Bullring N IO Birmingham Shopping Centre AT Shopping Centre BRIDGE ST IG New Street AV KING EDWARDS ROAD N Driving Distance A38 4 mins Walking Distance 12 mins HOLIDAY ST E KINGSTON ROW S O L HILL ST C C I V SUFFOLK STREET QUEENSWAY I C A456 BERKLEY ST The Mailbox Malmaison Hotel H SEVERN ST C A GRANVILLE ST MB RID BROAD ST Malt House GE ST M5/M42/M40 Walking Route 1 Leave the station via the ‘Victoria Square’ exit, keeping Boots to your left. -

Made for Investment

Made for Investment MADE FOR INVESTMENT 1 Welcome As a Midlander, I know very well how much this region has to The Midlands is made for offer. As a businessman, I am convinced that the UK’s future investment. As the heartbeat of economic prosperity can be driven by Midlands industry, Britain’s economy, and home to innovation and energy. The Midlands Engine is working hard over 440,000 large and small to accelerate growth across the whole region, and the public and private sectors are collaborating to bring this ambition to businesses, the region has huge fruition. We are showing the world that we are open for business potential – and the Midlands and confident about our future. Engine Partnership is focused on its global success. Our £200 billion economy covers a diverse and substantial area. Built on a globally significant advanced manufacturing base, it is home to over 10 million people. Our automotive, aerospace, life sciences, and professional services are all Contents internationally competitive, and we are known globally for our highly productive industrial sectors, research and innovative technologies. The region is home to some of the UK’s leading 03 Welcome to Midlands UK businesses and offers an enviable quality of life to those who 04 Introducing Midlands Engine choose to invest here. 05 Map As the most connected region in the UK, we are truly plugged into the world stage, with excellent road, rail and air networks, 06–22 Midlands UK Destination Partners and 92% of the UK’s population within a four hour commute. The arrival of HS2 will have a transformative effect, 23–46 Midlands UK Commercial Partners strengthening the region’s already unparalleled connectivity Sir John Peace Chair of the Midlands Engine and access to global markets. -

Phase One to Centenary Square

Transport Case Study Birmingham Westside Metro Extension - Phase One to Centenary Square Client: West Midlands Combined Authority Technical Features... (supporting Colas Rail as part of the Midland Metro Barhale’s scope on this extension included: Alliance) • Undertaking bulk earthworks Location: Birmingham City Centre • Managing demolition and hydro-demolition work Duration: 17 Months • Installing drainage and ducting • Constructing reinforced concrete retaining walls • Tram stop structural foundations In Brief... • Subway widening The Midland Metro Alliance is working on a ten year programme of • Statue foundations work to deliver tram extensions across the West Midlands. Barhale are • Standard track and floating track slab structures a sub-alliance partner whose remit is to deliver the civil engineering The drainage works varied in depth from 2m up to 6m deep in elements of the work. One of the projects is the first phase of the a congested city centre environment. Methods employed were Birmingham Westside Metro extension, which will see the line traditional open cut, timber headed tunnels and some caisson shaft extended from Grand Central to Centenary Square. These works will work for the deeper sewer connections. Some of the challenges aid regeneration across the city and prepare for the Commonwealth during excavation for the drainage works were the high volume of Games that Birmingham will be hosting in 2022. underground utilities and the thick layers of concrete and asphalt built up over years of city centre development. Barhale, as an approved Severn Trent water contractor, were able to manage and co-ordinate all 106 connections. The subway widening was an existing subway beneath a major arterial route in Birmingham city centre, which was required to be widened to accommodate both trams and general traffic. -

Office Insight – Birmingham Q3 2020

Office Insight – Birmingham Q3 2020. Office Insight – Birmingham Q3 2020. Not quite bustling Birmingham but getting there… Following a subdued Q2 in which the UK saw a peak in Great British outdoors in the form of a summer ‘staycation’. the number of coronavirus cases and deaths, businesses However, the latter part of the quarter has seen a noticeable went from working in the office to working from home on uptick in activity, with businesses now focusing on their mass overnight. The start of Q3 was typically quiet, with route through the recovery phase of this crisis. many people taking the opportunity to embrace the 1 Colmore Square 103 Colemore Row Signs of Life • Tom Tom traffic data indicated increased levels of road usage in Birmingham, with traffic levels on Monday 14th September seeing just a 26% reduction (compared to a year earlier) against a 63% reduction on Monday 8th June 2020 (compared to a year earlier). • Initial stats from the Eat Out to Help Out scheme also suggested increased activity levels. The parliamentary constituency of Ladywood, which covers most of the city centre, recorded 402,000 claimed meals over the month of August. Many restaurants hailed the success of the scheme and continued it on themselves into September without the Government’s support. • Footfall data recorded by Wireless Social shows increased footfall in Birmingham city centre since the easing of lockdown restrictions. Footfall on 6th June was recorded at 88% below the average seen in February 2020, compared to just a fall of 43% on the 6th September. Office Insight – Birmingham Q3 2020. -

Building Birmingham: a Tour in Three Parts of the Building Stones Used in the City Centre

Urban Geology in the English Midlands No. 2 Building Birmingham: A tour in three parts of the building stones used in the city centre. Part 2: Centenary Square to Brindleyplace Ruth Siddall, Julie Schroder and Laura Hamilton This area of central Birmingham has undergone significant redevelopment over the last two decades. Centenary Square, the focus of many exercises, realised and imagined, of civic centre planning is dominated by Symphony Hall and new Library of Birmingham (by Francine Houben and completed in 2013) and the areas west of Gas Street Basin are unrecognisable today from the derelict industrial remains and factories that were here in the 1970s and 80s. Now this region is a thriving cultural and business centre. This walking tour takes in the building stones used in old and new buildings and sculpture from Centenary Square, along Broad Street to Oozells Square, finishing at Brindleyplace. Brindleyplace; steps are of Portland Stone and the paving is York Stone, a Carboniferous sandstone. The main source on architecture, unless otherwise cited is Pevsner’s Architectural Guide (Foster, 2007) and information on public artworks is largely derived from Noszlopy & Waterhouse (2007). This is the second part in a three-part series of guides to the building stones of Birmingham City Centre, produced for the Black Country Geological Society. The walk extends the work of Shilston (1994), Robinson (1999) and Schroder et al. (2015). The walk starts at the eastern end of Centenary Square, at the Hall of Memory. Hall of Memory A memorial to those who lost their lives in the Great War, The Hall of Memory has a prominent position in the Gardens of Centenary Square. -

Jewellery Quarter Development Site

JEWELLERY QUARTER DEVELOPMENT SITE FOR SALE WITH PLANNING PERMISSION LAND AT 20-25 LEGGE LANE JEWELLERY QUARTER BIRMINGHAM B1 3LD PROPERTY REFERENCE: 15889 FREEHOLD OPPORTUNITY SITE EXTENDING TO 0.78 ACRES (0.32 HECTARES) GROSS PLANNING PERMISSION FOR 100 APARTMENTS UNCONDITIONAL OFFERS INVITED FOR THE FREEHOLD INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS APPROXIMATE BOUNDARIES FOR IDENTIFICATION PURPOSES ONLY. LAND AT 20-25 LEGGE LANE PROPERTY REFERENCE:15889 JEWELLERY QUARTER AVISON YOUNG | 3 BRINDLEYPLACE | BIRMINGHAM | B1 2JB BIRMINGHAM B1 3LD THE PROPERTY IS LOCATED IN AN AREA OF BIRMINGHAM’S CITY CENTRE KNOWN AS THE JEWELLERY QUARTER, WHICH LIES TO THE NORTH-WEST OF THE CORE OF THE CITY CENTRE. More specifically, the site is situated to the south of Legge Lane and is surrounded by a mix of residential and commercial uses together with redevelopment schemes under construction. The property is situated a short walk from local Jewellery Quarter amenities including The Chamberlain Clock (5 minutes), St Paul’s Square (8 minutes) and Jewellery Quarter Rail Station and Tram Stop (8 minutes). City centre amenities also available within the wider surrounding area include Brindleyplace, Paradise, Birmingham Library, The Bullring and The Mailbox. Nearby mainline rail travel can be accessed at Snow Hill Station (16 minutes’ walk), New Street Station (20 minutes’ walk) and Moor Street Station (23 minutes’ walk) offering connections to London (1 hour 25 minutes’ duration), Manchester (1 hour 27 minutes’ duration) and Liverpool (1 hour 40 minutes’ duration). Junction 6 of the M6 Motorway at the intersection with the A38M is located approximately 3.5 miles distant and Junction 1 of the M5 Motorway is located approximately 3.7 miles distant via the A41 Birmingham Road. -

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017

Birmingham City Council Planning Committee 06 July 2017 I submit for your consideration the attached reports for the East team. Recommendation Report No. Application No / Location / Proposal Defer – Informal Approval 8 2016/08285/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Demolition of existing extension and stable block, repair and restoration works to Rookery House to convert to 15 no. one & two-bed apartments with cafe/community space. Residential development comprising 40 no. residential dwellinghouses on adjoining depot sites to include demolition of existing structures and any associated infrastructure works. Repair and refurbishment of Entrance Lodge building. Refer to DCLG 9 2016/08352/PA Rookery House, The Lodge and adjoining depot sites 392 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 9SE Listed Building Consent for the demolition of existing single storey extension, chimney stack, stable block and repair and restoration works to include alterations to convert Rookery House to 15 no. self- contained residential apartments and community / cafe use - (Amended description) Approve - Conditions 10 2017/04018/PA 57 Stoney Lane Yardley Birmingham B25 8RE Change of use of the first floor of the public house and rear detached workshop building to 18 guest bedrooms with external alterations and parking Page 1 of 2 Corporate Director, Economy Approve - Conditions 11 2017/03915/PA 262 High Street Erdington Birmingham B23 6SN Change of use of ground floor retail unit (Use class A1) to hot food takeaway (Use Class A5) and installation of extraction flue to rear Approve - Conditions 12 2017/03810/PA 54 Kitsland Road Shard End Birmingham B34 7NA Change of use from A1 retail unit to A5 hot food takeaway and installation of extractor flue to side Approve - Conditions 13 2017/02934/PA Stechford Retail Park Flaxley Parkway Birmingham B33 9AN Reconfiguration of existing car parking layout, totem structures and landscaping. -

Savills Birmingham

7 8 9 Continue on Red Tour, fi nishing at Birmingham Grand Central. Grand Birmingham at nishing fi Tour, Red on Continue 14.45 - 15.30 - 14.45 by Rob Wells (Savills Planning) (Savills Wells Rob by Proceed onto Red Walking Tour towards Moonlit Park, presented presented Park, Moonlit towards Tour Walking Red onto Proceed 13.45 - 14.45 - 13.45 LUNCH 13.00 - 13.45 - 13.00 Moonlit Park The Mailbox Birmingham Canal Side The Lee Bank area, on which Park Central is located, had become The site was the location of the Royal Mail’s main sorting offi ce for A canal basin in the centre of Birmingham, England, where the MADE) run down over time and required redevelopment. Birmingham in the 1970s. It was the largest mechanised sorting Worcester and Birmingham Canal meets the BCN Main Line. It is - Designer (Urban Gomez Patricia by guided and Woodward offi ce (20ac fl oor area) in the country and the largest building in located on Gas Street, off Broad Street, and between the Mailbox Gary by accompanied Tour, Walking Green onto Proceed Crest Nicholson redeveloped the area with new mid and high rise 13.00 - 11.00 properties. Numerous 1960s residential buildings were demolished, Birmingham. Redevelopment/ conversion commenced in 1998 by and Brindleyplace canal-side developments. the, then owner, Birmingham Development Company. The building including Haddon Tower (July 23, 2006). 1 Room Meeting included two hotels with a total of 300 rooms, 15,850 sq. m The Birmingham Canal, completed in 1773, terminated at Old Construction began in late 2005 (170,000 sg.