Farewell August 12 and 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

What to Expect from doctor atomic Opera has alwayS dealt with larger-than-life Emotions and scenarios. But in recent decades, composers have used the power of THE WORK DOCTOR ATOMIC opera to investigate society and ethical responsibility on a grander scale. Music by John Adams With one of the first American operas of the 21st century, composer John Adams took up just such an investigation. His Doctor Atomic explores a Libretto by Peter Sellars, adapted from original sources momentous episode in modern history: the invention and detonation of First performed on October 1, 2005, the first atomic bomb. The opera centers on Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, in San Francisco the brilliant physicist who oversaw the Manhattan Project, the govern- ment project to develop atomic weaponry. Scientists and soldiers were New PRODUCTION secretly stationed in Los Alamos, New Mexico, for the duration of World Alan Gilbert, Conductor War II; Doctor Atomic focuses on the days and hours leading up to the first Penny Woolcock, Production test of the bomb on July 16, 1945. In his memoir Hallelujah Junction, the American composer writes, “The Julian Crouch, Set Designer manipulation of the atom, the unleashing of that formerly inaccessible Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer source of densely concentrated energy, was the great mythological tale Brian MacDevitt, Lighting Designer of our time.” As with all mythological tales, this one has a complex and Andrew Dawson, Choreographer fascinating hero at its center. Not just a scientist, Oppenheimer was a Leo Warner and Mark Grimmer for Fifty supremely cultured man of literature, music, and art. He was conflicted Nine Productions, Video Designers about his creation and exquisitely aware of the potential for devastation Mark Grey, Sound Designer he had a hand in designing. -

Johannes Brahms Symphony No

PH17085.Booklet.Brahms_Booklet 24.01.18 15:12 Seite 1 Edition Günter Profil Hänssler JOHANNES BRAHMS SYMPHONY NO. 4 ACADEMIC FESTIVAL OVERTURE TRAGIC OVERTURE WDR Sinfonieorchester JUKKA-PEKKA SARASTE PH17085.Booklet.Brahms_Booklet 24.01.18 15:12 Seite 2 JOHANNES BRAHMS JOHANNES BRAHMS DEUTSCH Vierte Sinfonie e-moll op. 98 Johannes Brahms war, obzwar schon als Brahms glaubte anfangs, sich nicht In der Wintersaison kam der inzwischen Zwanzigjähriger von keinem Geringeren von dem übermächtigen Vorbild Beet- berühmt gewordene Wahlwiener seinen Seine letzte Sinfonie komponierte Brahms als Robert Schumann als “Berufener” hovens freimachen zu können, der die zahlreichen Konzertverpflichtungen nach; in zwei Phasen: je zwei Sätze in den Som- gepriesen, ein sehr selbstkritischer Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten der Sinfonie so im Sommer pflegte er sich in landschaft- mern 1884 und 1885 in Mürzzuschlag. Im “Spätentwickler”. Von seiner Vaterstadt vollendet ausgeschöpft hatte. Deshalb lich schön gelegenen Standquartieren September des zweiten Jahres war das Hamburg enttäuscht, wo er gerne Diri- gingen seiner „Ersten“ viele bedeutende zu erholen und in deren idyllischer Werk vollendet. Brahms gab das Manu- gent der Philharmonischen Gesellschaft Werke voraus, das “Deutsche Requiem”, Ruhe seinen schöpferischen Plänen skript des ersten Satzes über das Ehepaar geworden wäre, siedelte er sich im das erste Klavierkonzert, die beiden nachzugehen. Herzogenberg der verehrten Clara Schu- Herbst 1862 endgültig in Wien an. Hier großen Orchester-Serenaden sowie die mann zur Kenntnis. Gleichzeitig korres- konnte er einen lebendigeren Kontakt Haydn-Variationen. Im November 1878 Unmittelbar nach Vollendung der Drit- pondierte er mit Hans von Bülow wegen zur Tradition der großen Klassiker ge- endlich, Johannes Brahms war bereits 43 ten Sinfonie 1883 beschäftigte sich der Uraufführung durch dessen berühmte winnen als anderswo. -

Brahms Complete Edition

BRAHMS COMPLETE EDITION CONTENT Page ORCHESTRAL WORKS: CD 1 – 5 . 2 CONCERTOS: CD 6 – 8 . 7 CHAMBER MUSIC: CD 9 – 19 . 9 PIANO AND ORGAN WORKS: CD 20– 28 . 18 LIEDER: CD 29 – 35 . 30 VOCAL ENSEMBLES: CD 36 – 39 . 44 CHORAL WORKS: CD 40 – 43 . .53 WORKS FOR CHORUS AND ORCHESTRA: CD 44 – 46 . 61 ORCHESTRAL WORKS CD 1 [77’51] Symphony no. 1 in C minor, op. 68 [44’19] c-moll · en ut mineur A 1. Un poco sostenuto – Allegro [13’25] B 2. Andante sostenuto [8’26] C 3. Un poco Allegretto e grazioso [4’48] D 4. Adagio – Più Andante – Allegro non troppo, ma con brio [17’38] Symphony no. 3 in F major, op. 90 [33’24] F-dur · en fa majeur E 1. Allegro con brio [9’40] F 2. Andante [8’14] G 3. Poco Allegretto [6’17] H 4. Allegro [9’13] BERLINER PHILHARMONIKER · HERBERT VON KARAJAN CD 2 [74’29] Symphony no. 2 in D major, op. 73 [40’14] D-dur · en ré majeur A 1. Allegro non troppo [15’45] B 2. Adagio non troppo – L’istesso tempo, ma grazioso [9’47] 2 C 3. Allegretto grazioso (Quasi Andantino) – Presto ma non assai – Tempo I [5’22] D 4. Allegro con spirito [9’20] BERLINER PHILHARMONIKER · HERBERT VON KARAJAN Serenade no. 2 in A major, op. 16 [33’55] A-dur · en la majeur E 1. Allegro moderato [9’35] F 2. Scherzo. Vivace – Trio [2’38] G 3. Adagio non troppo [9’41] H 4. Quasi Menuetto – Trio [5’44] I 5. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

3982.Pdf (118.1Kb)

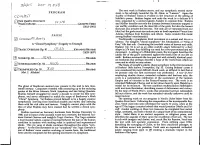

II 3/k·YC)) b,~ 1'1 ,~.>u The next work in Brahms oeuvre, and our symphonic second move . PROGRAM ment, is his achingly beautiful Op. 82, Niinie, or "Lament." Again the Ci) I~ /6':; / duality of Brahms vision is evident in the structure of the setting of Schiller's poem. Brahms begins and ends the work in a delicate 6/4 v time, separated by a central majestic Andante in common time. Brahms lD~B~=':~i.~.~~ f~.:..::.?.................... GIU~3-':;') and Schiller describe not only the distance between humanity trapped in ............. our earthly condition and the ideal life of the gods, but also the lament "" that pain also invades the heavens. Not only are we separated from our bliss, but the gods must also endure pain as death separated Venus from Adonis, Orpheus from Euridice, and others. Some consider this music PAUSE among Brahms' most beautiful. r;J ~ ~\.e;Vll> I Boe (5 Traditionally a symphonic third movement is a minuet and trio or a scherzo. For tonight's "choral symphony" the Schicksalslied, or "Song of A "Choral Symphony" -Tragedy to Triumph Fate," fills that role. Continuing the two-fold vision of heaven and earth, Brahms' Op. 54 is set as an other-worldly adagio followed by a fiery ~ TRAGIC OVERTURE Op. 81 .......... L~:.s..:>.................JOHANNES BRAHMS allegro in 3/4 time, thus fulfilling our need for a two-part minuet and trio (1833-1897) movement. A setting of a HOideriein poem, the text again describes the idyllic life of the god's contrasted against the fearful fate of our life on NANIE Op. -

2019•20 Season

bso andris nelsons music director 2019•20 season week 5 j.s. bach beethoven brahms bartók s seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus thomas adès artistic partner season sponsors Better Health, Brighter Future There is more that we can do to help improve people’s lives. Driven by passion to realize this goal, Takeda has been providing society with innovative medicines since our foundation in 1781. Today, we tackle diverse healthcare issues around the world, from prevention to life-long support and our ambition remains the same: to find new solutions that make a positive difference, and deliver better medicines that help as many people as we can, as soon as we can. With our breadth of expertise and our collective wisdom and experience, Takeda will always be committed to improving the future of healthcare. Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited www.takeda.com Table of Contents | Week 5 7 bso news 1 5 on display in symphony hall 16 bso music director andris nelsons 18 the boston symphony orchestra 2 2 celebrating malcolm lowe 2 4 this week’s program Notes on the Program 26 The Program in Brief… 27 J.S. Bach 35 Ludwig van Beethoven 43 Johannes Brahms 51 Béla Bartók 55 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artist 63 Sir András Schiff 68 sponsors and donors 80 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 8 3 symphony hall information the friday preview on october 18 is given by author/composer jan swafford. program copyright ©2019 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. program book design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photo by Marco Borggreve cover design by BSO Marketing BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Symphony Hall, 301 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, MA 02115-4511 (617) 266-1492 bso.org “A work of art is the trace of a magnificent struggle.” GRACE HARTIGAN On view now Grace Hartigan, Masquerade, 1954. -

Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: a Study of the Late Songs

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs Natilan Casey-Ann Crutcher [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Crutcher, Natilan Casey-Ann, "Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3886. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3886 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs Natilan Crutcher Dissertation submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In Voice Performance Hope Koehler, DMA, Chair Evan MacCarthy, Ph.D. William Koehler, DMA David Taddie, Ph.D. General Hambrick, BFA School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2019 Keywords: Johannes Brahms, Lieder, Late Style Copyright 2019 Natilan Crutcher Abstract Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs Natilan Crutcher Johannes Brahms has long been viewed as a central figure in the Classical tradition during a period when the standards of this tradition were being altered and abandoned. -

Olivier Messiaen's Personal Expression of Faith in His Major Solo and Chamber Works with Piano from 1940 to 1944

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2012 Olivier Messiaen's Personal Expression of Faith in His Major Solo and Chamber Works with Piano from 1940 to 1944 Marie Arlou C. Borillo West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Borillo, Marie Arlou C., "Olivier Messiaen's Personal Expression of Faith in His Major Solo and Chamber Works with Piano from 1940 to 1944" (2012). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4835. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4835 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olivier Messiaen’s Personal Expression of Faith in His Major Solo and Chamber Works with Piano from 1940 to 1944 Marie Arlou C. Borillo Dissertation submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance Keith Jackson, D.M.A. -

“Country Band” March Historical Perspectives, Stylistic Considerations, and Rehearsal Strategies

“COUNTRY BAND” MARCH HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES, STYLISTIC CONSIDERATIONS, AND REHEARSAL STRATEGIES by Jermie Steven Arnold A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Instrumental Conducting Committee: Director Program Director ___________________________________ Director of the School of Music Dean, College of Visual and Performing Arts Date: Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA “Country Band” March Historical Perspectives, Stylistic Considerations, And Rehearsal Strategies A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts at George Mason University By Jermie Steven Arnold Master of Music Brigham Young University, 2007 Bachelor of Music Brigham Young University, 2002 Director: Tom Owens, Associate Professor School of Music Spring Semester 2014 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2014 Jermie Steven Arnold All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION For my lovely wife, Amber and my wonderful children, Jacob, Kyle and Bethany. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is truly amazing how paths cross and doors open. Knowing there isn’t such a thing as a coincidence reminds me of the many blessings I have received during the journey to my Doctoral degree. I am grateful to my immediate and extended family who sacrificed much so that I could pursue my dreams. Their unyielding support kept me focused and determined. It is their faith in me that motivated the completion of this dissertation. To those I first called mentors and now friends: Mark Camphouse, Dennis Layendecker, Anthony Maiello, Tom Owens, and Rachel Bergman, thank you for your wisdom, expertise and most importantly your time. -

JOHANNES BRAHMS Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg; Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna

JOHANNES BRAHMS Born May 7, 1833 in Hamburg; died April 3, 1897 in Vienna. Tragic Overture, Opus 81 (1880) PREMIERE OF WORK: Vienna, December 20, 1880 Vienna Philharmonic Hans Richter, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 13 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani and strings Many of Brahms’ works were produced in pairs: Piano Sonatas, Opus 1 and Opus 2; Piano Quartets, Opus 25 and Opus 26; String Quartets, Opus 51; Clarinet Sonatas, Opus 120; even the first two Symphonies, the sets of Liebeslieder Waltzes and the Serenades. These twin pieces seem to have been the result of a surfeit of material — as Brahms was working out his ideas for a composition in a particular genre, he produced enough material to spin off a second work of similar type. Though the two orchestral overtures of 1880, Academic Festival and Tragic, were also written in tandem, they have about them more the quality of complementary balance than of continuity. Academic Festival is bright in mood and lighthearted in its musical treatment of some favorite German student drinking songs. The Tragic Overture, on the other hand, is somber and darkly heroic. Of them, Brahms wrote to his biographer Max Kalbeck, “One overture laughs, the other weeps.” And further, to his friend and publisher, Fritz Simrock, “Having composed this jolly Academic Festival Overture, I could not refuse my melancholy nature the satisfaction of composing an overture for a tragedy.” Brahms never gave any additional clues to the nature of the Tragic Overture. The Tragic Overture is comparable in form and expression to the first movement of a symphony. -

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Ninth Season Through Brahms CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 22–August 13, 2011 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Through Brahms the ninth season July 22–August 13, 2011 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 2 Season Dedication 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 4 Welcome from the Executive Director 4 Board, Administration, and Mission Statement 5 Through Brahms Program Overview 6 Essay: “Johannes Brahms: The Great Romantic” by Calum MacDonald 8 Encounters I–IV 11 Concert Programs I–VI 30 String Quartet Programs 37 Carte Blanche Concerts I–IV 50 Chamber Music Institute 52 Prelude Performances 61 Koret Young Performers Concerts 64 Café Conversations 65 Master Classes 66 Open House 67 2011 Visual Artist: John Morra 68 Listening Room 69 Music@Menlo LIVE 70 2011–2012 Winter Series 72 Artist and Faculty Biographies 85 Internship Program 86 Glossary 88 Join Music@Menlo 92 Acknowledgments 95 Ticket and Performance Information 96 Calendar Cover artwork: Mertz No. 12, 2009, by John Morra. Inside (p. 67): Paintings by John Morra. Photograph of Johannes Brahms in his studio (p. 1): © The Art Archive/Museum der Stadt Wien/ Alfredo Dagli Orti. Photograph of the grave of Johannes Brahms in the Zentralfriedhof (central cemetery), Vienna, Austria (p. 5): © Chris Stock/Lebrecht Music and Arts. Photograph of Brahms (p. 7): Courtesy of Eugene Drucker in memory of Ernest Drucker. Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 69) and Ani Kavafian (p. 75): Christian Steiner. Paul Appleby (p. 72): Ken Howard. Carey Bell (p. 73): Steve Savage. Sasha Cooke (p. 74): Nick Granito.