273KB***Rationalising and Simplifying the Presumption Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore

Damien Cheong ____________________________________________________________ Selling Security: The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore DAMIEN CHEONG Abstract The Internal Security Act (ISA) of Singapore has been transformed from a se- curity law into an effective political instrument of the Singapore government. Although the government's use of the ISA for political purposes elicited negative reactions from the public, it was not prepared to abolish, or make amendments to the Act. In the wake of September 11 and the international campaign against terrorism, the opportunity to (re)legitimize the government's use of the ISA emerged. This paper argues that despite the ISA's seeming importance in the fight against terrorism, the absence of explicit definitions of national security threats, either in the Act itself, or in accompanying legislation, renders the ISA susceptible to political misuse. Keywords: Internal Security Act, War on Terrorism. People's Action Party, Jemaah Islamiyah. Introduction In 2001/2002, the Singapore government arrested and detained several Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) operatives under the Internal Security Act (ISA) for engaging in terrorist activities. It was alleged that the detained operatives were planning to attack local and foreign targets in Singa- pore. The arrests outraged human rights groups, as the operation was reminiscent of the government's crackdown on several alleged Marxist conspirators in1987. Human rights advocates were concerned that the current detainees would be dissuaded from seeking legal counsel and subjected to ill treatment during their period of incarceration (Tang 1989: 4-7; Frank et al. 1991: 5-99). Despite these protests, many Singaporeans expressed their strong support for the government's actions. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

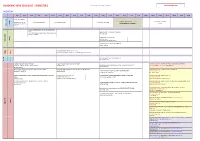

Class Timetable for Lecture/Seminar

ACADEMIC YEAR 2019/2020 - SEMESTER 2 (1920) Page 1: Semester 2 AY19-20 Timetable_(ver 9 January 2020) Version 9 January 2020 MONDAY 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 LC1016 LARC LECTURE LC1003 LAW OF CONTRACT LECTURE {Yale 2} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL {Yale 2} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL BURTON ONG, DORA NEO, SANDRA BOOYSEN, KELRY LOI, {Yale 2} ELEANOR WONG, LIM LEI TAN ZHONG XING, ALLEN SNG, MINDY CHEN-WISHART Weekly THENG, SONITA JEYAPATHY, RUBY LEE YEAR 1 CORE 1 YEAR LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC2007 CONSTITUTIONAL & ADMIN LAW LECTURE {Yale LC2006A, B & C EQUITY & TRUSTS SECTIONS ((A) B) & (C) {Yale 4} 3} LC2006D, E & F EQUITY & TRUSTS SECTIONS (D), (E) & (F) RACHEL LEOW (A); KELRY LOI (B); TAN YOCK LIN (C) THIO LI-ANN, SWATI JHAVERI, KEVIN TAN, DIAN SHAH, RACHEL LEOW (D); TAN YOCK LIN (E); TAN WEI MENG (F) CORE YEAR 2 Weekly JACLYN NEO, MARCUS TEO LC6378 Doctoral Workshop DAMIAN CHALMERS D CORE Weekly G LL4044V/LL5044V/LL6044V MEDIATION LL4019V/LL5019/ LL6019V CREDIT & SECURITY LL4063V/LL5063V/LL6063V BUSINESS & FINANCE FOR LAWYERS LL4371/LL5371/LL6371 CHARITY LAW TODAY INTENSIVE [WEEK 1-3] JOEL LEE, MARCUS LIM DORA NEO STEPHEN PHUA/JAMES LEONG MATTHEW HARDING LL4372/LL5372/LL6372 INTERNATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW INTENSIVE LL4402/LL5402/LL6402 CORPORATE INSOLVENCY LL4024V/LL5024V/LL6024V INDONESIAN LAW LL4205V/LL5205V/LL6205V/LLD5205V MARITIME CONFLICT OF LAWS [WEEK 1-3] WEE MENG SENG GARY -

Competing Narratives and Discourses of the Rule of Law in Singapore

Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2012] 298–330 SHALL THE TWAIN NEVER MEET? COMPETING NARRATIVES AND DISCOURSES OF THE RULE OF LAW IN SINGAPORE Jack Tsen-Ta Lee∗ This article aims to assess the role played by the rule of law in discourse by critics of the Singapore Government’s policies and in the Government’s responses to such criticisms. It argues that in the past the two narratives clashed over conceptions of the rule of law, but there is now evidence of convergence of thinking as regards the need to protect human rights, though not necessarily as to how the balance between rights and other public interests should be struck. The article also examines why the rule of law must be regarded as a constitutional doctrine in Singapore, the legal implications of this fact, and how useful the doctrine is in fostering greater solicitude for human rights. Singapore is lauded for having a legal system that is, on the whole, regarded as one of the best in the world,1 and yet the Government is often vilified for breaching human rights and the rule of law. This is not a paradox—the nation ranks highly in surveys examining the effectiveness of its legal system in the context of economic compet- itiveness, but tends to score less well when it comes to protection of fundamental ∗ Assistant Professor of Law, School of Law, Singapore Management University. I wish to thank Sui Yi Siong for his able research assistance. 1 See e.g., Lydia Lim, “S’pore Submits Human Rights Report to UN” The Straits Times (26 February 2011): On economic, social and cultural rights, the report [by the Government for Singapore’s Universal Periodic Review] lays out Singapore’s approach and achievements, and cites glowing reviews by leading global bodies. -

![Ho Yean Theng Jill V Public Prosecutor [2003]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3974/ho-yean-theng-jill-v-public-prosecutor-2003-1943974.webp)

Ho Yean Theng Jill V Public Prosecutor [2003]

Ho Yean Theng Jill v Public Prosecutor [2003] SGHC 280 Case Number : MA 70/2003, Cr M 15/2003 Decision Date : 14 November 2003 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Yong Pung How CJ Counsel Name(s) : K S Rajah SC (Harry Elias Partnership) and Peter Ong Lip Cheng (Ong Lip Cheng and Rajendran) for applicant/appellant; Christopher Ong Siu Jin (Deputy Public Prosecutor) for respondent Parties : Ho Yean Theng Jill — Public Prosecutor Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Charge – Joinder of similar offences – Whether series of connected acts should be tried as separate offences or one composite offence – Section 170 Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 1985 Rev Ed) – Section 71 Penal Code (Cap 224, 1985 Rev Ed) Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Compounding of offences – Maid abuse by de facto employer – Whether court should grant consent for compounding of offence – Section 199 Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 1985 Rev Ed) Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Sentencing – Principles – Voluntarily causing hurt – Maid abuse by de facto employer – Whether sentence manifestly excessive – Section 323 Penal Code (Cap 24, 1985 Rev Ed) 1 The appellant was convicted in the Magistrate’s Court on five charges of voluntarily causing hurt under s 323 of the Penal Code and was sentenced to a total of four months’ imprisonment. She appealed against both conviction and sentence. After hearing counsel’s arguments, I dismissed the appeal against both conviction and sentence. I now give my reasons. Preliminary issue 2 In the petition of appeal filed on 21 April 2003, the appellant essentially challenged the magistrate’s findings of fact. Thereafter, the appellant filed a criminal motion for leave to file a supplementary petition of appeal on 10 September 2003. -

SEMESTER 2 Page 1: Semester 2 AY1617 Timetable Version 2 November 2016

ACADEMIC YEAR 2016/2017 - SEMESTER 2 Page 1: Semester 2 AY1617 Timetable Version 2 November 2016 MONDAY 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 LC1016 LARC LECTURE {Yale 1} LC2009 PRO BONO SERVICE {Yale 1} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL ELEANOR WONG, LIM LEI LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL THENG, SONITA JEYAPATHY, Workshop begins in Semester 2 {Yale 1} Weekly RUBY LEE YEAR 1CORE LC2007 CONSTITUTIONAL & ADMIN LAW LECTURE {Yale 2} LC2006A EQUITY & TRUSTS (A) SEMINAR THIO LI-ANN, SWATI JHAVERI, LYNETTE CHUA, KEVIN TAN, TAN YOCK LIN TAN HSIEN-LI TERESA LC2006 B EQUITY & TRUSTS (B) LECTURE {Yale 3} Weekly NICOLE ROUGHAN, BARRY CROWN YEAR 2CORE LC2006C EQUITY & TRUSTS (C) SEMINAR JAMES PENNER LC3001B EVIDENCE (B) LECTURE {Yale 3} UPPER HO HOCK LAI, CHIN TET YUNG, JEFFREY PINSLER, KENNETH KHOO Weekly YR CORE LC5405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (A) NG-LOY WEE LOON Weekly GD CORE GD LL4054V/LL5054V/LL6054V/LLD5054V LL4407/LL5407/LL6407 LAW OF INSURANCE LL4219/LL5219/LL6219 THE TRIAL OF JESUS IN WESTERN LEGAL THOUGHT DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL SALE OF GOODS YEO HWEE YING LL4405A/LL5405A/LC5405A/LL6405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY A INTENSIVE [WEEK 1; 9 Jan 2017] JOSEPH WEILER NG-LOY WEE LOON MICHAEL BRIDGE LL4074V/LL5074V/LL6074V MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS (M&A) LL4195V/LL5195V/LL6195V INT'L ECONOMIC LAW & RELATIONS LL4300/LL5300/LL6300 COPYRIGHT IN THE INTERNET AGE UMAKANTH VAROTTIL WANG JIANGYU LL4071V/LL5071V/LL6071V GLOBAL -

SAL Annual Report 2002-03.Pdf

SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT 1 APRIL 2002 – 31 MARCH 2003 Mission Statement Building up the intellectual capital, capability and infrastructure of members of the Singapore Academy of Law. Promotion of esprit de corps among members of the Singapore Academy of Law. SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT 1 APRIL 2002 – 31 MARCH 2003 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 8Annual Report 16 Highlights of the Year 20 Annual Accounts 2002/2003 The stately facade of City Hall is an emblem for all that our legal environment strives to be ... ... elegantly conceived, quietly commanding and very much a part of every Singaporeans’ life. Foreword01 By The Honourable The Chief Justice Yong Pung How President, Singapore Academy of Law The Singapore Academy of Law LawNet as a legal portal to a memoranda of understanding strives to bring together the regional level through a specially to promote its role as a major various branches of the legal constituted Sub-Committee on element of dispute resolution fraternity in a spirit of mutual the Future of LawNet. solutions in the region and the respect and camaraderie. Singapore International Without doubt, the Academy Among the many firsts by the Arbitration Centre embarked on plays a vital role in engendering Academy was the introduction a new phase of its development a shared pride in the practice, of the Council of Law Reporting with an alliance with the learning and dissemination of in connection with the Singapore Business Federation. the law. Academy’s move to take over the responsibility of publishing It has been a year of many The year just past bears the Singapore Law Reports — beginnings for the Academy testament to the Academy’s also a first — from the beginning with new alliances, proposals efforts to improve the legal of 2003. -

Law Minister K Shanmugam SC ’84 a Word from the Editor CONTENTS

VOL. 07 ISSUE 02 JUL - DEC 2008 ISSN: 0219-6441 LawLinkThe Alumni Magazine of the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law Interview with Lord Leonard Hoffmann Obligations IV Conference 5th ASLI Conference Commencement 2008 Cover Story Law Minister K Shanmugam SC ’84 A word from the Editor CONTENTS Going “Glocal” Dean’s Message 1 - From Local Roots to Global Growth Retirement of the Chief Justice of the ome key appointments in the Singapore Legal Sector were made this year. Mr Federal Court of Malaysia 2 K. Shanmugam SC ’84, previously in legal practice and a longtime Member of SParliament, was propelled to his new appointment as the Minister for Law on 1 May. Professor Walter Woon ’81, previously the Solicitor-General, etched up a notch to Law School Highlights: his appointment as the Attorney-General on 11 April. Mrs Koh Juat Jong ’88, previously Donors’ List 2 the Registrar of the Supreme Court, was appointed as the new Solicitor-General also on 11 April. Together with the Chief Justice Chan Sek Keong ’61, the top posts are New Advisory Board Member 2 now filled with our home-grown NUS Law School alumni. This is something to be 5th Professorial Lecture proud of. by Professor Leong Wai Kum 3 We are featuring Minister Shanmugam in our cover story. He was gracious enough, 5th ASLI Conference 4 due to his longstanding association with the Faculty as an Advisory Board member, to Obligations IV Conference 5 squeeze in the time to chat with us, whilst addressing the issues of the day, such as the step-by-step implementation of the Report of the Committee to Develop the Singapore Alumni Reunion in Shanghai 8 Legal Sector (the VK Rajah Report). -

SAL Annual Report 2001

SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT Financial year 2001/2002 MISSION STATEMENT Building up the intellectual capital, capability and infrastructure of members of the Singapore Academy of Law. Promotion of esprit de corps among members of the Singapore Academy of Law. SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW ANNUAL REPORT 1 April 2001 - 31 march 2002 5Foreword 7Introduction 13 Annual Report 2001/2002 43 Highlights of the Year 47 Annual Accounts 2001/2002 55 Thanking the Fraternity Located in City Hall, the Singapore Academy of Law is a body which brings together the legal profession in Singapore. FOReWoRD SINGAPORE ACADEMY OF LAW FOREWORD by Chief Justice Yong Pung How President, Singapore Academy of Law From a membership body in 1988 with a staff strength of less than ten, the Singapore Academy of Law has grown to become an internationally-recognised organisation serving many functions and having two subsidiary companies – the Singapore Mediation Centre and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre. The year 2001/2002 was a fruitful one for the Academy and its subsidiaries. The year kicked off with an immersion programme in Information Technology Law for our members. The inaugural issue of the Singapore Academy of Law Annual Review of Singapore Cases 2000 was published, followed soon after by the publication of a book, “Developments in Singapore Law between 1996 and 2000”. The Singapore International Arbitration Centre launched its Domestic Arbitration Rules in May 2001, and together with the Singapore Mediation Centre, launched the Singapore Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy for resolving “.sg” domain name disputes. The Academy created a Legal Development Fund of $5 million to be spread over 5 years for the development of the profession in new areas of law and practice. -

![Law Society of Singapore V Ong Ying Ping [2005]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3511/law-society-of-singapore-v-ong-ying-ping-2005-4433511.webp)

Law Society of Singapore V Ong Ying Ping [2005]

Law Society of Singapore v Ong Ying Ping [2005] SGHC 120 Case Number : OS 1084/2004, NM 27/2005 Decision Date : 15 July 2005 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Chao Hick Tin JA; Andrew Phang Boon Leong JC; Yong Pung How CJ Counsel Name(s) : Ramesh Tiwary (Edmond Pereira and Partners) for the applicant; C R Rajah SC (Tan Rajah and Cheah) and Chia Boon Teck (Chia Yeo Partnership) for the respondent Parties : Law Society of Singapore — Ong Ying Ping Legal Profession – Show cause action – Person accompanying advocate and solicitor to interview with prisoner was prisoner's wife – Advocate and solicitor misleading prison officers as to identity of person accompanying by failing to disclose person's relationship with prisoner in disregard of prison rules on visitation – Whether advocate and solicitor's conduct amounting to misconduct unbefitting an advocate and solicitor – Whether appropriate for court to grant application – Appropriate penalty – Sections 83(2)(h), 98(5) Legal Profession Act (Cap 161, 2001 Rev Ed) 15 July 2005 Andrew Phang Boon Leong JC (delivering the judgment of the court): Introduction 1 The present case involves a charge against the respondent pursuant to s 83(2)(h) of the Legal Profession Act (Cap 161, 2001 Rev Ed) (“LPA”). The charge itself, as formulated by the Law Society of Singapore (“the Law Society”), reads as follows: Charge That Ong Ying Ping [the respondent] is guilty of misconduct unbefitting an advocate and solicitor as an officer of the Supreme Court or as a member of an honourable profession within the meaning of section 83[(2)](h) of the Legal Profession Act (Chapter 161) in that he on [10th] October 2001 at Queenstown Remand Prison did fail to disclose that one Ms Tan Teck Cheng Linda is related to the prisoner he was interviewing, Ivan Ng Chin Hoe and misled the prison officers to believe that she was his assistant. -

Wrongful Convictions in Singapore: a General Survey of Risk Factors Siyuan CHEN Singapore Management University, [email protected]

Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School Of Law School of Law 1-2010 Wrongful Convictions in Singapore: A General Survey of Risk Factors Siyuan CHEN Singapore Management University, [email protected] Eunice CHUA Singapore Management University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Courts Commons, Judges Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Citation CHEN, Siyuan and CHUA, Eunice. Wrongful Convictions in Singapore: A General Survey of Risk Factors. (2010). Singapore Law Review. 28, 98-122. Research Collection School Of Law. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/933 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School Of Law by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. Singapore Law Review Published in Singapore Law Review 2010, Vol. 28, Pages 98-122. (2010) 28 SingL Rev, 98-122 WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS IN SINGAPORE: A GENERAL SURVEY OF RISK FACTORS CHEN SiyUAN AND EUNICE CHUA" This article seeks to raise awarenessabout the potentialfor wrongfiul convictions in Singapore by analysing the factors commonly identified as contributing towards wrongful convictions in otherjurisdictions, including institutionalfailures and suspect evidence. It also considers whether the social conditions in Singapore are favourable to discovering and publicising wrongful convictions. The authors come to the conclusion that Singapore does well on a number offi-onts and no sweeping reforms are necessary However there are areas ofrisk viz the excessive focus on crime control rather than due process, which require some tweaking of the system. -

LAWLINK Vol 1 No.1 January-June 2002 the Alumni Magazine of the National University of Singapore Law School ISSN: 0219-6441

LAWLINK Vol 1 No.1 January-June 2002 The Alumni Magazine of the National University of Singapore Law School ISSN: 0219-6441 Artist-alumnus Namiko Chan ’97 with Uma, her gift to the Law School Contents 03 Message from Dean Tan Cheng Han ‘87 04 Law School Highlights LAWLINK can be accessed on-line at 9 A Word from the http://www.law.nus.edu.sg/alumni 0 ALAWMNUS Feature Namiko has donated one of her works – Uma – to the Law School in honour of her 4 Alumni News Editor teachers. In addition, the Law School has 1 It is about time we had a comprehensive purchased another of Namiko’s paintings – alumni magazine. It is about time, too, for Untitled 4 – to be dedicated in memory of stronger alumni relations. Our Law School two colleagues who passed away in recent 8 Future Alumni boasts a rich tradition leading back to years, Ricardo Almeida and Peter English. 1 pre-independence Singapore. Our alumni fill the ranks of government, the private sector, We are also inspired by our students and the arts community and almost every other alumni who continue to go beyond the law 2 ClassAction niche of professional life in Singapore. It is to engage in community and public interest 2 perhaps because we are the only law school work. In this issue, we profile an alumnus in the country that we omit to identify more who is heading Club Rainbow, a charity strongly with it. Thus, we often take for dedicated to helping children with chronic meantime, we welcome comments on granted the fact that we, the alumni of the and potentially life-threatening illnesses.