Here Dr LWL Was to Live

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore

Damien Cheong ____________________________________________________________ Selling Security: The War on Terrorism and the Internal Security Act of Singapore DAMIEN CHEONG Abstract The Internal Security Act (ISA) of Singapore has been transformed from a se- curity law into an effective political instrument of the Singapore government. Although the government's use of the ISA for political purposes elicited negative reactions from the public, it was not prepared to abolish, or make amendments to the Act. In the wake of September 11 and the international campaign against terrorism, the opportunity to (re)legitimize the government's use of the ISA emerged. This paper argues that despite the ISA's seeming importance in the fight against terrorism, the absence of explicit definitions of national security threats, either in the Act itself, or in accompanying legislation, renders the ISA susceptible to political misuse. Keywords: Internal Security Act, War on Terrorism. People's Action Party, Jemaah Islamiyah. Introduction In 2001/2002, the Singapore government arrested and detained several Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) operatives under the Internal Security Act (ISA) for engaging in terrorist activities. It was alleged that the detained operatives were planning to attack local and foreign targets in Singa- pore. The arrests outraged human rights groups, as the operation was reminiscent of the government's crackdown on several alleged Marxist conspirators in1987. Human rights advocates were concerned that the current detainees would be dissuaded from seeking legal counsel and subjected to ill treatment during their period of incarceration (Tang 1989: 4-7; Frank et al. 1991: 5-99). Despite these protests, many Singaporeans expressed their strong support for the government's actions. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

170702Mindmap Copy

Who said what Numerous allegations have been made in the ongoing feud between Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and his siblings, from misuse of power to a conict Against Lee Hsien Loong of interest in preparing the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s last will. Insight charts the Against Teo Chee Hean • Allegation: PM Lee misused his claims and accusations in the dispute over the fate of 38, Oxley Road. • Allegation: Committee focused power to prevent the house from solely on challenging validity of being demolished demolition clause in Mr Lee’s will PM’s response: Denied the DPM Teo’s response: Not true that “baseless” allegations, will refute committee bent on preventing them in a ministerial statement in demolition of the house Parliament tomorrow • Allegation: Committee did not • Allegation: PM Lee made disclose options in prior exchanges, contradictory statements about only identied members and its their father’s wishes and the house terms of reference when “forced in public and private into the daylight” Ms Indranee Rajah’s DPM Teo’s response: Nothing response: Notes that secret about committee; it is like Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s numerous other committees last will specically Cabinet sets up to consider specic accepts and Against Ho Ching Against K. Shanmugam issues acknowledges that DPM Tharman Allegation: Has a pervasive Allegation: Conict of interest demolition may not take place. • • Shanmugaratnam’s inuence on government, well being on ministerial committee, response: Cabinet has beyond her job scope having advised the late Mr Lee and • Allegation: Did not challenge the numerous committees family about the house last will in court when probate was on whole range of granted • Allegation: Removed the late Mr Mr Shanmugam’s response: issues, to help think Lee’s items from house without PM’s response: Wanted to avoid a Calls the claim ridiculous; says through difcult choices approval; represented the Prime public ght that would tarnish the nothing he said precluded him from Minister’s Ofce despite not family name serving in committee. -

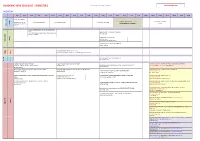

Class Timetable for Lecture/Seminar

ACADEMIC YEAR 2019/2020 - SEMESTER 2 (1920) Page 1: Semester 2 AY19-20 Timetable_(ver 9 January 2020) Version 9 January 2020 MONDAY 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 LC1016 LARC LECTURE LC1003 LAW OF CONTRACT LECTURE {Yale 2} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL {Yale 2} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL BURTON ONG, DORA NEO, SANDRA BOOYSEN, KELRY LOI, {Yale 2} ELEANOR WONG, LIM LEI TAN ZHONG XING, ALLEN SNG, MINDY CHEN-WISHART Weekly THENG, SONITA JEYAPATHY, RUBY LEE YEAR 1 CORE 1 YEAR LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC2007 CONSTITUTIONAL & ADMIN LAW LECTURE {Yale LC2006A, B & C EQUITY & TRUSTS SECTIONS ((A) B) & (C) {Yale 4} 3} LC2006D, E & F EQUITY & TRUSTS SECTIONS (D), (E) & (F) RACHEL LEOW (A); KELRY LOI (B); TAN YOCK LIN (C) THIO LI-ANN, SWATI JHAVERI, KEVIN TAN, DIAN SHAH, RACHEL LEOW (D); TAN YOCK LIN (E); TAN WEI MENG (F) CORE YEAR 2 Weekly JACLYN NEO, MARCUS TEO LC6378 Doctoral Workshop DAMIAN CHALMERS D CORE Weekly G LL4044V/LL5044V/LL6044V MEDIATION LL4019V/LL5019/ LL6019V CREDIT & SECURITY LL4063V/LL5063V/LL6063V BUSINESS & FINANCE FOR LAWYERS LL4371/LL5371/LL6371 CHARITY LAW TODAY INTENSIVE [WEEK 1-3] JOEL LEE, MARCUS LIM DORA NEO STEPHEN PHUA/JAMES LEONG MATTHEW HARDING LL4372/LL5372/LL6372 INTERNATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW INTENSIVE LL4402/LL5402/LL6402 CORPORATE INSOLVENCY LL4024V/LL5024V/LL6024V INDONESIAN LAW LL4205V/LL5205V/LL6205V/LLD5205V MARITIME CONFLICT OF LAWS [WEEK 1-3] WEE MENG SENG GARY -

Report of the Ministerial Committee on 38 Oxley Road

REPORT OF THE MINISTERIAL COMMITTEE ON 38 OXLEY ROAD TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Background Chapter 2: Historical and heritage significance Chapter 3: Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s thinking and wishes on the property Chapter 4: Possible options for the property Chapter 5: Committee’s views 2 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND 1. Founding Prime Minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s former home at 38 Oxley Road (henceforth referred to as the “Property”) is a single-storey bungalow surrounded by low-rise residential developments. 2. The issue of whether to preserve Mr Lee’s home after his passing, to demolish it, or some other option has become a matter of public interest. Shortly after Mr Lee’s passing on 23 March 2015, PM Lee Hsien Loong addressed this issue in Parliament on 13 April 2015, where he said that “there is no immediate issue of demolition of the house, and no need for the Government to make any decision now”, given that Dr Lee Wei Ling “intended to continue living in the Property”. He also stated that “if and when Dr Lee Wei Ling no longer lives in the House, Mr Lee has stated his wishes as to what then should be done…however, it will be up to the Government of the day to consider the matter”. 3. Though there is no immediate need for a decision, given the significant public interest in the Property, the Cabinet 1 approved setting up a Ministerial Committee (“Committee”) on 1 June 2016 to consider the various options. The Committee was asked to prepare drawer plans of various options and their implications, with the benefit of views of those who had directly discussed the matter with Mr Lee, so that a future Government can refer to these plans and make a considered and informed decision when the time came to decide on the matter. -

Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia

TRANSPARENCY AND AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The 1997–98 Asian economic crisis raised serious questions for the remaining authoritarian regimes in Southeast Asia, not least the hitherto outstanding economic success stories of Singapore and Malaysia. Could leaders presiding over economies so heavily dependent on international capital investment ignore the new mantra among multilateral financial institutions about the virtues of ‘transparency’? Was it really a universal functional requirement for economic recovery and advancement? Wasn’t the free flow of ideas and information an anathema to authoritarian rule? In Transparency and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Asia Garry Rodan rejects the notion that the economic crisis was further evidence that ulti- mately capitalism can only develop within liberal social and political insti- tutions, and that new technology necessarily undermines authoritarian control. Instead, he argues that in Singapore and Malaysia external pres- sures for transparency reform were, and are, in many respects, being met without serious compromise to authoritarian rule or the sanctioning of media freedom. This book analyses the different content, sources and significance of varying pressures for transparency reform, ranging from corporate dis- closures to media liberalisation. It will be of equal interest to media analysts and readers keen to understand the implications of good governance debates and reforms for democratisation. For Asianists this book offers sharp insights into the process of change – political, social and economic – since the Asian crisis. Garry Rodan is Director of the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Australia. ROUTLEDGECURZON/CITY UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES Edited by Kevin Hewison and Vivienne Wee 1 LABOUR, POLITICS AND THE STATE IN INDUSTRIALIZING THAILAND Andrew Brown 2 ASIAN REGIONAL GOVERNANCE: CRISIS AND CHANGE Edited by Kanishka Jayasuriya 3 REORGANISING POWER IN INDONESIA The politics of oligarchy in an age of markets Richard Robison and Vedi R. -

Competing Narratives and Discourses of the Rule of Law in Singapore

Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2012] 298–330 SHALL THE TWAIN NEVER MEET? COMPETING NARRATIVES AND DISCOURSES OF THE RULE OF LAW IN SINGAPORE Jack Tsen-Ta Lee∗ This article aims to assess the role played by the rule of law in discourse by critics of the Singapore Government’s policies and in the Government’s responses to such criticisms. It argues that in the past the two narratives clashed over conceptions of the rule of law, but there is now evidence of convergence of thinking as regards the need to protect human rights, though not necessarily as to how the balance between rights and other public interests should be struck. The article also examines why the rule of law must be regarded as a constitutional doctrine in Singapore, the legal implications of this fact, and how useful the doctrine is in fostering greater solicitude for human rights. Singapore is lauded for having a legal system that is, on the whole, regarded as one of the best in the world,1 and yet the Government is often vilified for breaching human rights and the rule of law. This is not a paradox—the nation ranks highly in surveys examining the effectiveness of its legal system in the context of economic compet- itiveness, but tends to score less well when it comes to protection of fundamental ∗ Assistant Professor of Law, School of Law, Singapore Management University. I wish to thank Sui Yi Siong for his able research assistance. 1 See e.g., Lydia Lim, “S’pore Submits Human Rights Report to UN” The Straits Times (26 February 2011): On economic, social and cultural rights, the report [by the Government for Singapore’s Universal Periodic Review] lays out Singapore’s approach and achievements, and cites glowing reviews by leading global bodies. -

![Ho Yean Theng Jill V Public Prosecutor [2003]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3974/ho-yean-theng-jill-v-public-prosecutor-2003-1943974.webp)

Ho Yean Theng Jill V Public Prosecutor [2003]

Ho Yean Theng Jill v Public Prosecutor [2003] SGHC 280 Case Number : MA 70/2003, Cr M 15/2003 Decision Date : 14 November 2003 Tribunal/Court : High Court Coram : Yong Pung How CJ Counsel Name(s) : K S Rajah SC (Harry Elias Partnership) and Peter Ong Lip Cheng (Ong Lip Cheng and Rajendran) for applicant/appellant; Christopher Ong Siu Jin (Deputy Public Prosecutor) for respondent Parties : Ho Yean Theng Jill — Public Prosecutor Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Charge – Joinder of similar offences – Whether series of connected acts should be tried as separate offences or one composite offence – Section 170 Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 1985 Rev Ed) – Section 71 Penal Code (Cap 224, 1985 Rev Ed) Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Compounding of offences – Maid abuse by de facto employer – Whether court should grant consent for compounding of offence – Section 199 Criminal Procedure Code (Cap 68, 1985 Rev Ed) Criminal Procedure and Sentencing – Sentencing – Principles – Voluntarily causing hurt – Maid abuse by de facto employer – Whether sentence manifestly excessive – Section 323 Penal Code (Cap 24, 1985 Rev Ed) 1 The appellant was convicted in the Magistrate’s Court on five charges of voluntarily causing hurt under s 323 of the Penal Code and was sentenced to a total of four months’ imprisonment. She appealed against both conviction and sentence. After hearing counsel’s arguments, I dismissed the appeal against both conviction and sentence. I now give my reasons. Preliminary issue 2 In the petition of appeal filed on 21 April 2003, the appellant essentially challenged the magistrate’s findings of fact. Thereafter, the appellant filed a criminal motion for leave to file a supplementary petition of appeal on 10 September 2003. -

Official Publication of the Law Society of Singapore | August 2016

Official Publication of The Law Society of Singapore | August 2016 Thio Shen Yi, Senior Counsel President The Law Society of Singapore A RoadMAP for Your Journey The 2016 Mass Call to the Bar will be held this month on 26 Modern psychology tells us employees are not motivated and 27 August over three sessions in the Supreme Court. by their compensation – that’s just a hygiene factor. Pay Over 520 practice trainees will be admitted to the roll of mustn’t be an issue in that it must be fair, and if there is a Advocates & Solicitors. differential with their peers, then ceteris paribus, it cannot be too significant. Along with the Chief Justice, the President of the Law Society has the opportunity to address the new cohort. I Instead, enduring motivation is thought to be driven by three had the privilege of being able to do so last year in 2015, elements, mastery, autonomy, and purpose. There’s some and will enjoy that same privilege this year. truth in this, even more so in the practice of law, where we are first and foremost, members of an honourable The occasion of speaking to new young lawyers always profession. gives me pause for thought. What can I say that will genuinely add value to their professional lives? Making Mastery: The challenge and opportunity to acquire true motherhood statements is as easy as it is pointless. They expertise. There is a real satisfaction in being, and becoming, are soon forgotten, even ignored, assuming that they are really good at something. Leading a cross-border deal heard in the first place. -

SEMESTER 2 Page 1: Semester 2 AY1617 Timetable Version 2 November 2016

ACADEMIC YEAR 2016/2017 - SEMESTER 2 Page 1: Semester 2 AY1617 Timetable Version 2 November 2016 MONDAY 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 19:00 19:30 20:00 20:30 21:00 LC1016 LARC LECTURE {Yale 1} LC2009 PRO BONO SERVICE {Yale 1} LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL ELEANOR WONG, LIM LEI LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL LC1016 LARC TUTORIAL THENG, SONITA JEYAPATHY, Workshop begins in Semester 2 {Yale 1} Weekly RUBY LEE YEAR 1CORE LC2007 CONSTITUTIONAL & ADMIN LAW LECTURE {Yale 2} LC2006A EQUITY & TRUSTS (A) SEMINAR THIO LI-ANN, SWATI JHAVERI, LYNETTE CHUA, KEVIN TAN, TAN YOCK LIN TAN HSIEN-LI TERESA LC2006 B EQUITY & TRUSTS (B) LECTURE {Yale 3} Weekly NICOLE ROUGHAN, BARRY CROWN YEAR 2CORE LC2006C EQUITY & TRUSTS (C) SEMINAR JAMES PENNER LC3001B EVIDENCE (B) LECTURE {Yale 3} UPPER HO HOCK LAI, CHIN TET YUNG, JEFFREY PINSLER, KENNETH KHOO Weekly YR CORE LC5405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (A) NG-LOY WEE LOON Weekly GD CORE GD LL4054V/LL5054V/LL6054V/LLD5054V LL4407/LL5407/LL6407 LAW OF INSURANCE LL4219/LL5219/LL6219 THE TRIAL OF JESUS IN WESTERN LEGAL THOUGHT DOMESTIC & INTERNATIONAL SALE OF GOODS YEO HWEE YING LL4405A/LL5405A/LC5405A/LL6405A LAW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY A INTENSIVE [WEEK 1; 9 Jan 2017] JOSEPH WEILER NG-LOY WEE LOON MICHAEL BRIDGE LL4074V/LL5074V/LL6074V MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS (M&A) LL4195V/LL5195V/LL6195V INT'L ECONOMIC LAW & RELATIONS LL4300/LL5300/LL6300 COPYRIGHT IN THE INTERNET AGE UMAKANTH VAROTTIL WANG JIANGYU LL4071V/LL5071V/LL6071V GLOBAL -

Sektor Pelancongan Anggar Rugi RM105 Juta, Sektor Perniagaan

Ex-PM: Hsien Loong’s siblings trying to bring him down Free Malaysia Today July 5, 2017 The former Singapore prime minister vouches for the integrity of Lee Hsien Loong in parliamentary debate over abuse of power accusations made against the prime minister. SINGAPORE: Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong says Lee Hsien Yang’s goal is to bring his elder brother, Lee Hsien Loong, down as prime minister. Channel NewsAsia quoted the former prime minister of Singapore as saying the family feud between Hsien Loong and his two siblings had tarnished Singapore’s reputation. He asked if the two siblings were whistle-blowing in an effort to save Singapore or waging a personal vendetta against Hsien Loong. “It is now no longer a cynical parlour game. If the Lee siblings choose to squander the good name and legacy of Lee Kuan Yew and tear their relationship apart, it is tragic but a private family affair. “But if in the process of their self-destruction, they destroy Singapore too, that is a public affair.” Goh was speaking on the second day of a parliamentary discussion over a public dispute between the children of Lee Kuan Yew, following allegations by Hsien Yang and his sister Lee Wei Ling that Hsien Loong was abusing his powers to block the demolition of their 38 Oxley Road family home. Channel NewsAsia quoted Goh as saying Singaporeans were getting sick and tired of all this. “There must be a clear conclusion at the end of this debate. Either we clear the PM over the allegation on his abuse of power, or we censure him,” he said. -

Differences Surface

Differences surface A family feud over the fate of founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s house at 38, Oxley Road spilt into the public sphere in June, two years after Mr Lee’s death. Two of his children, Dr Lee Wei Ling and Mr Lee Hsien Yang, accused their brother, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, of misusing his power and not honouring their late father’s wish to demolish the family home. Timeline JUNE 14 JUNE 19 which he said “the Singapore Dr Lee and Mr Lee Hsien Yang post a PM Lee issues a statement and a video Government is very litigious and has a statement on Facebook saying they apologising to Singaporeans for the pliant court system”. have lost condence in PM Lee and harm caused by the protracted and that they fear the use of organs of publicly aired dispute with his siblings. AUG 4 state against them. They also accuse AGC says it led application to begin him and his wife Ho Ching of wanting to JULY 3 - 4 contempt of court proceedings against make use of the late Mr Lee’s legacy to Parliament debates the allegations Mr Li for his comments on the further their political ambitions for their over the abuse of power. Over two days, Singapore judiciary. son Li Hongyi. PM Lee denies their 36 ministers and MPs speak, with the accusations. People’s Action Party lifting its Whip. OCT 17 PM Lee says his siblings’ “allegations AGC serves court papers on Mr Li at JUNE 15 - 16 have been aired, have been answered Harvard University in the United States.