John Muir Writings My First Summer in the Sierra by John Muir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park July 29, 2015 - September 1, 2015 1, September - 2015 29, July Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where NPS Photo NPS 1904. Grove, Mariposa Monarch, Fallen the astride Soldiers” “Buffalo Cavalry 9th D, Troop Volume 40, Issue 6 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

May 6 - Hwy 120 Closed Late Fall- Late Spring to 395 Lake West of This Point & June 2, 2003 Eleanor Lee Vining O’Shaughnessy Dam 120

Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park Vol. 3 Issue 5 Experience Your Yosemite To day America N May 6 - Hwy 120 closed late fall- late spring To 395 Lake west of this point & June 2, 2003 Eleanor Lee Vining O’Shaughnessy Dam 120 e Hetch Riv r ne d Hetchy lum oa uo Tioga R Backpackers' T y Tuolumne Pass h Campground c t Entrance Hetch e (Wilderness tch H Hetchy He Permit Required) Meadows Lembert Entrance Facilities and campgrounds Dome Fork White na Mount Camp along Tioga Da Dana To Mather Wolf Road available summer only 13,053 ft Yosemite E 3,979 m 120 v e r d g Mount a re o Tuolumne Big e R n d Hoffmann National Park May a Meadows L R a g Oak o 10,850 ft y o R io a a 3,307 m Lake T Visitor e Flat d g ll io Center F T o r Entrance k Porcupine Tenaya Yosemite Flat Lake Important Phone Numbers Hodgdon mn 120 olu e Creek u Riv Meadow T er S ork Olmsted To o u th F Emergency 911 (from hotel room 9-911) Manteca Point Road and Weather/General Park North Tuolumne k e Clouds Grove Valley Dome re C Rest Information 209/372-0200 Tamarack ya Yosemite Visitor en a Mount Flat Falls Center T Crane Big Lyell Campground Reservations 800/436-7275 O Yosemite er Merced Flat a Half iv 13,114 ft k F d R 3,997 m l Dome e Grove a Valley c r t e Merced Trailhead R M Lodging Reservations 559/252-4848 o Hw Lake a To y 120 El Capitan d Glacier Tioga Road Point Vernal closed late fall- Fall & late spring Tunnel east of this point Arch Bridalveil Sentinel Nevada Rock View Fall Dome Fall El Entrance Portal Il lilo uett e C ree er Rd k To iv Glacie oint -

Centennial Issue

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK Centennial Issue is been 100 years ture an appearance by since President Ben- President George Bush, jamin Harrison who has been invited. A I signed into law the number of other dig- act that established a large nitaries will also be in area around Yosemite attendance, and about Valley and the Mariposa the time of the ceremony, Big Trees as Yosemite a time capsule will be National Park. For the buried in front of the remainder of 1990 and Yosemite Valley Visitor until October, 1991, the Center. National Park Service Other centennial pro- will be celebrating the grams include a major park's centennial and ask- symposium that has been ing people to contemplate scheduled from October Yosemite's history and 13 to 19 in Concord and how the preservation Yosemite . The focus of idea, engendered in the symposium will be Yosemite, has taken on on natural and cultural new meaning in the face resource issues and on of global environmental future directions for park changes . There are hopes management. There are that from history we can also at least two museum learn the Iessons that will exhibits that will be open allow us to manage and through the end of the use Yosemite with the year. One is at the Califor- same foresight and wis- nia Academy of Sciences dom exemplified by those in San Francisco, the who first legislated the other at Yosemite 's own preservation of the place. museum . Please call the Participation in Yosemite Association at Yosemite's centennial (209) 379-2317 for infor- celebration is open to mation about any of everyone, and a variety of these programs or events. -

John Muir and Gifford Pinchot Were Two Men Who Held Very Different Ideas About the Environment

Cool Views Activity – Muir and Pinchot: Respecting Each Other’s Differences Article John Muir and Gifford Pinchot were two men who held very different ideas about the environment. John Muir believed that the wilderness should be preserved. Gifford Pinchot thought that the environment should be conserved. Both men were leaders in the environmental movement during the nineteenth century. John Muir was a naturalist, explorer and writer who campaigned for the preservation of the American wilderness. He was born on April 28, 1838, in Dunbar, Scotland. At the age of eleven, his family moved to the United States. Living on a farm in Wisconsin, John learned about the beauty and usefulness of nature. As an adult, he founded the Sierra Club. His many books (such as, The Mountains of California and Our National Parks), articles and speeches helped to create many protected wilderness areas, including Yosemite National Park. To Mr. Muir, the wilderness was a place to be respected and revered without the intrusion of humankind. He saw foresters and other conservationists as meddling intruders into nature's world. Gifford Pinchot was the first American to take up the profession of forestry and the first head of the U.S. Forest Service. He was outspoken in his manner and known to appoint women and African Americans to office during a time when most governmental leaders did not. He was born in 1865 to a wealthy family from Pennsylvania. He was educated in the best schools and traveled to Europe, where he learned about the concept of conservation in forestry. Gifford helped to popularize the idea of conservation in the United States. -

Investigating the El Capitan Rock Avalanche

BY GREG STOCK INVESTIGATING THE EL CapITAN ROCK AVALANCHE t 2:25 on the morning of March 26, 1872, one of avalanche, an especially large rockfall or rockslide that the largest earthquakes recorded in California extends far beyond the cliff where it originated. Most Ahistory struck along the Owens Valley fault near Yosemite Valley rockfall debris accumulates at the base the town of Lone Pine just east of the Sierra Nevada. The of the cliffs, forming a wedge-shaped deposit of talus. earthquake leveled most buildings in Lone Pine and sur- Occasionally, however, debris from a rock avalanche will rounding settlements, and killed 23 people. Although extend out much farther across the valley floor. seismographs weren’t yet available, the earthquake is esti- Geologist Gerald Wieczorek of the U.S. Geological mated to have been about a magnitude 7.5. Shock waves Survey and colleagues have identified at least five rock from the tembler radiated out across the Sierra Nevada. avalanche deposits in Yosemite Valley. The largest of these On that fateful morning, John Muir was sleeping in occurred in Tenaya Canyon, at the site of present-day a cabin near Black’s Hotel on the south side of Yosemite Mirror Lake. Sometime in the past, a rock formation on Valley, near present-day Swinging Bridge. The earth- the north wall of the canyon just east of and probably quake shook the naturalist out of bed. Realizing what similar in size to Washington Column collapsed into was happening, Muir bolted outside, feeling “both glad Tenaya Canyon. The rock debris piled up against the and frightened” and shouting “A noble earthquake!” He south canyon wall to a depth of over 100 feet. -

Mechanisms and Rate of Emplacement of the Half Dome Granodiorite

Mechanisms and rate of emplacement of the Half Dome Granodiorite Kyle J. Krajewski Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Allen F. Glazner Introduction Continental crust is largely composed of high-silica intrusive rocks such as granite, and understanding the mechanisms of granitic pluton emplacement is essential for understanding the formation of continental crust. With its incredible exposure, few places are comparable to the Tuolumne Intrusive Suite (TIS) in Yosemite National Park for studying these mechanisms. The TIS is interpreted as a comagmatic assemblage of concentric intrusions (Bateman and Dodge, 1970). The silica contents of the plutons increase from the margins inwards, transitioning from tonalities to granites, through both abrupt and gradational boundaries (Bateman and Chappell, 1979; Fig. 1). The age of the TIS also has a distinct trend, with the oldest rocks cropping out at the margins and the youngest toward the center. To accommodate this time variation, the TIS is hypothesized to have formed from multiple pulses of magma (Bateman and Chappell, 1979) . Understanding the volume, timing, and interaction of these pulses with one another has led to the formation of three main hypotheses to explain the evolution of the TIS. Figure 1. Simplified geologic map of the TIS. Insets of rocks on the right illustrate petrographic variation through the suite. Bateman and Chappell (1979) hypothesized that as the suite cooled, it solidified from the margins inward. Solidification of the chamber was prolonged by additional pulses of magma. These pulses expanded the chamber through erosion of the wall rock and breaking through the overlying carapace, creating a ballooning magma chamber. -

Yosemite National Park Foundation Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yosemite National Park California Contact Information For more information about Yosemite National Park, Call (209) 372-0200 (then dial 3 then 5) or write to: Public Information Office, P.O. Box 577, Yosemite, CA 95389 Park Description Through a rich history of conservation, the spectacular The geology of the Yosemite area is characterized by granitic natural and cultural features of Yosemite National Park rocks and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years have been protected over time. The conservation ethics and ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and then tilted to form its policies rooted at Yosemite National Park were central to the relatively gentle western slopes and the more dramatic eastern development of the national park idea. First, Galen Clark and slopes. The uplift increased the steepness of stream and river others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, beds, resulting in formation of deep, narrow canyons. About ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln’s signing 1 million years ago, snow and ice accumulated, forming glaciers the Yosemite Grant in 1864. The Yosemite Grant granted the at the high elevations that moved down the river valleys. Ice Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State thickness in Yosemite Valley may have reached 4,000 feet during of California stipulating that these lands “be held for public the early glacial episode. The downslope movement of the ice use, resort, and recreation… inalienable for all time.” Later, masses cut and sculpted the U-shaped valley that attracts so John Muir led a successful movement to establish a larger many visitors to its scenic vistas today. -

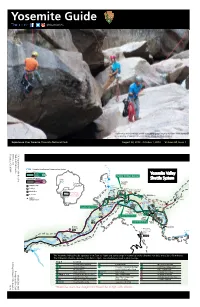

Yosemite Guide @Yosemitenps

Yosemite Guide @YosemiteNPS Yosemite's rockclimbing community go to great lengths to clean hard-to-reach areas during a Yosemite Facelift event. Photo by Kaya Lindsey Experience Your America Yosemite National Park August 28, 2019 - October 1, 2019 Volume 44, Issue 7 Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Hetch Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Hetchy Shuttle Fall Yosemite Tuolumne Village Campground Meadows Lower Yosemite Parking The Ansel Fall Adams Yosemite l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area Valley l T Area in inset: al F e E1 t 5 Restroom Yosemite Valley i 4 m 9 The Ahwahnee Shuttle System se Yo Mirror Upper 10 3 Walk-In 6 2 Lake Campground seasonal 11 1 Wawona Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 15 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking Curry Upper Sentinel Village Pines Beach il Trailhead E6 a Curry Village Parking r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M E4 ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E5 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a a lv W e i The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Cairo to Sa7el Magazine with Our Handy ‘Pop-It-In-Your-Bag’ Sized Sa7el Directory Will Roll out Across the Length of Sa7el at the Beginning of July

TABLE OF CONTENTS July - August 2021 Meet BIG ZEE FASHION Beachwear and Accessories BEAUTY Top Hair Products Summer 2021 FEATURES EEA ( Egypt Entrepreneur Awards) Winners Beach Fashions Through the Ages Gadget News Summer 2021 Summer Activities Sa7el Activities for Kids Summer Horoscopes WELLBEING COVID vaccine FAQ & Myth Busting Summer Chicken Salad ENTERTAINMENT AUC: Meet the Author Diwan New Arrivals and Best-sellers In Theaters Now TV Series to Catch Art Scene Crave Wellbeing Schedules What’s New OUR TEAM Founder & Publisher Shorouk Abbas Editor-in-Chief Atef Abdelfattah Content Director Hilary Diack Copyediting Nahla Samaha General Manager Nihad Ezz El Din Amer Sales and Marketing Manager Nahed Hamy Assistant to General Manager Lobna Farag Sales Director Engy Nabil Digital Marketing Specialist Mariam Abd El Ghaffar Digital Content Aliaa El Sherbini Digital Content Creators Mariam Elhamy, Basem Mansour Social Media Ezz Eldin Darwish Graphic Designers Ahmed Salah, Essam Ibrahim Photography Mohamed Meteab Accountant Mohamed Mahmoud Distribution Ahmed Haidar, Mohamed El Saied, Mohamed Najah, Mohamed Shaker Mekkawy Printing IPH (International Printing House) Produced by Cairo West Publications Issued with registration from London No. 837545 Cairo Alex Desert Road - El Naggar Office Building 2 This magazine is created and owned by Cairo West Advertising. Managing Director: Shorouk Abbas Email: [email protected] For advertising contact: Tel: +2 0122 4300 100 +2 02 3532 0588 Email: [email protected] This magazine is not for sale. Cairo East, a subsidiary magazine for Katameya & New Cairo All rights reserved. Reproduction in any form is strictly prohibited without prior consent from the publisher. If you have been holding your breath, waiting for the months, the weeks, the days and the minutes to tick by so you can hit the beach… exhale. -

THE YOSEMITE by John Muir CHAPTER I The

THE YOSEMITE By John Muir CHAPTER I The Approach to the Valley When I set out on the long excursion that finally led to California I wandered afoot and alone, from Indiana to the Gulf of Mexico, with a plant-press on my back, holding a generally southward course, like the birds when they are going from summer to winter. From the west coast of Florida I crossed the gulf to Cuba, enjoyed the rich tropical flora there for a few months, intending to go thence to the north end of South America, make my way through the woods to the headwaters of the Amazon, and float down that grand river to the ocean. But I was unable to find a ship bound for South America--fortunately perhaps, for I had incredibly little money for so long a trip and had not yet fully recovered from a fever caught in the Florida swamps. Therefore I decided to visit California for a year or two to see its wonderful flora and the famous Yosemite Valley. All the world was before me and every day was a holiday, so it did not seem important to which one of the world's wildernesses I first should wander. Arriving by the Panama steamer, I stopped one day in San Francisco and then inquired for the nearest way out of town. "But where do you want to go?" asked the man to whom I had applied for this important information. "To any place that is wild," I said. This reply startled him. He seemed to fear I might be crazy and therefore the sooner I was out of town the better, so he directed me to the Oakland ferry. -

3 They Are Wait- Ction: "Well It Ously, His Voice I ~?, ,K,~ Y White Nostrils ~, N I AM ~S~.N How Much All the Kings Men Owes to :The ~Y It Don T!

~~ h,,. ~p~ wnxxEN Robert Penn Warrea bit in the full- d to enjoy the othe`S from a ~sive climax of S.All the King's Men: n's o'n'es, and houseboy, who The Matrix of Experience :r, Duckfoot is it commitment 3 they are wait- ction: "Well it his voice iously, ~?, ,K,~N I AM ~s~.n white nostrils ~, how much All the Kings Men owes to :the y actual of ~y it don t! .. politics Louisiana in the 'go's, I can only be sure that p the pee out of if I had never gone #o live in Louisiana and if Huey bong had ool, a complete, ~'' not existed, the nove} would never have :been written.But this and you're here is far from,saying, that my "state" in AIZ the Kmg's is comfoik Men gent in ~° Louisiana or an ofsthe other fo fla the nostrils of r { Y rtj'-nine stars in our g), or id my i white-slick face #hat Willie Stark is the Iate Senator. What Louisiana and aside, which was Senator Long gave me was aline of thinking and feeling that ff his long white did eventuate ~ the.novel out Nhatever was In thesummer of 1434 I was offered a job—a much-needed.. cuzdling and and j, job—as assistant professor at the Louisiana State Unive~ity, in knew that every- Baton Rouge. It was.:"Huey Long's University," and definitely ever done or said L, on the make—with a sensational Football team and with money which.had been '` to spend even for assistant professors at a `time when assistant pride ass and his professors were being 5red, not hired—as I knew all too well.