Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Health Inequalities Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

The David Attenborough Building Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QY

Venue The David Attenborough Building Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QY http://www.conservation.cam.ac.uk/ Cambridge Cambridge is a university city and the county town of Cambridgeshire, England, on the River Cam about 50 miles (80 km) north of London. At the United Kingdom Census 2011, its population was 123,867, including 24,488 students. There is archaeological evidence of settlement in the area in the Bronze Age and in Roman Britain; under Viking rule, Cambridge became an important trading centre. The first town charters were granted in the 12th century, although city status was not conferred until 1951. Cambridge is the home of the University of Cambridge, founded in 1209 and one of the top five universities in the world. The university includes the Cavendish Laboratory, King's College Chapel, and the Cambridge University Library. The Cambridge skyline is dominated by the last two buildings, along with the spire of the Our Lady and the English Martyrs Church, the chimney of Addenbrooke's Hospital and St John's College Chapel tower. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology Silicon Fen with industries such as software and bioscience and many start-up companies spun out of the university. Over 40% of the workforce have a higher education qualification, more than twice the national average. Cambridge is also home to the Cambridge Biomedical Campus, one of the largest biomedical research clusters in the world, soon to be home to AstraZeneca, a hotel and relocated Papworth Hospital. Parker's Piece hosted the first ever game of Association football. The Strawberry Fair music and arts festival and Midsummer Fairs are held on Midsummer Common, and the annual Cambridge Beer Festival takes place on Jesus Green. -

Cambridgeshire Tydd St

C D To Long Sutton To Sutton Bridge 55 Cambridgeshire Tydd St. Mary 24 24 50 50 Foul Anchor 55 Tydd Passenger Transport Map 2011 Tydd St. Giles Gote 24 50 Newton 1 55 1 24 50 To Kings Lynn Fitton End 55 To Kings Lynn 46 Gorefield 24 010 LINCOLNSHIRE 63 308.X1 24 WHF To Holbeach Drove 390 24 390 Leverington WHF See separate map WHF WHF for service detail in this area Throckenholt 24 Wisbech Parson 24 390.WHF Drove 24 46 WHF 24 390 Bellamys Bridge 24 46 Wisbech 3 64 To Terrington 390 24. St. Mary A B Elm Emneth E 390 Murrow 3 24 308 010 60 X1 56 64 7 Friday Bridge 65 Thorney 46 380 308 X1 To Grantham X1 NORFOLK and the North 390 308 Outwell 308 Thorney X1 7 Toll Guyhirn Coldham Upwell For details of bus services To in this area see Peterborough City Council Ring’s End 60 Stamford and 7 publicity or call: 01733 747474 60 2 46 3 64 Leicester Eye www.travelchoice.org 010 2 X1 65 390 56 60.64 3.15.24.31.33.46 To 308 7 380 Three Holes Stamford 203.205.206.390.405 33 46 407.415.701.X1.X4 Chainbridge To Downham Market 33 65 65 181 X4 Peterborough 206 701 24 Lot’s Bridge Wansford 308 350 Coates See separate map Iron Bridge To Leicester for service detail Whittlesey 33 701 in this area X4 Eastrea March Christchurch 65 181 206 701 33 24 15 31 46 Tips End 203 65 F Chesterton Hampton 205 Farcet X4 350 9 405 3 31 35 010 Welney 115 To Elton 24 206 X4 407 56 Kings Lynn 430 415 7 56 Gold Hill Haddon 203.205 X8 X4 350.405 Black Horse 24.181 407.430 Yaxley 3.7.430 Wimblington Boots Drove To Oundle 430 Pondersbridge 206.X4 Morborne Bridge 129 430 56 Doddington Hundred Foot Bank 15 115 203 56 46. -

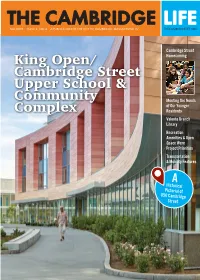

King Open/Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Complex

THE CAMBRIDGE LIFE FALL 2019 ISSUE 3, VOL.4 A PUBLICATION OF THE CITY OF CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS THECAMBRIDGELIFE.ORG Cambridge Street King Open/ Homecoming Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Meeting the Needs of Our Younger Complex Residents Valente Branch Library Recreation Amenities & Open Space Were Project Priorities Transportation & Mobility Features A Historical Pictorial of 850 Cambridge Street King Open/Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Complex Site Map Project Overview The 273,000 square foot facility at 850 Cambridge St. opened in September 2019 and houses the King Open School (JK-5), Cambridge Street Upper School (6-8), Cambridge Public Schools Administration, King Open Preschool, King Open Extended Day (KOED), Community Schools, and Valente Library The $159 million school and community complex is a net zero-ready project that consumes no fossil fuels onsite, has a highly efficient design to minimize energy demand, and incorporates the City’s largest solar array to renewably produce much of the energy needed. Remaining energy will come from the electrical grid, and when Cambridge secures 100% renewable electricity supply, the complex will achieve net zero emissions. Site amenities and open spaces include Gold Star Pool, two gyms, two basketball courts, Charles G. Rossi Bocce Court, five playgrounds, outdoor splash pad, Cambridge Street Plaza, Valente Reading Garden, a Learning Courtyard/Outdoor Classroom, and a 380-seat auditorium. “One of the important considerations throughout this entire process was to make sure we successfully met the needs of the students, staff, the school administration, the neighborhood, and users of Cambridge Street,” said Lisa Peterson, Deputy City Manager and King Open/Cambridge Street Upper School & Community Complex Project Manager, adding that an extensive community process was conducted. -

DAY 1: Cambridge

Expat Explore - Version: Sat Sep 25 2021 10:34:53 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 1/9 Itinerary for Great Britain Christmas Tour • Expat Explore Start Point: End Point: Outside Hotel Novotel at Greenwich Outside Hotel Novotel at Greenwich station, station, 173-185 Greenwich High Road, London, SE10 173-185 Greenwich High Road, London, SE10 8JA 8JA 06:30 hrs 17:30 hrs – 20:30 hrs Hotel lobby at Holiday Inn Express, Greenwich, 85 Bugsby Way, Greenwich, London, SE10 0GD 07:00 hrs DAY 1: Start of tour in London - Cambridge - York Welcome to your Christmas tour of Great Britain! Today you will fill your lungs with fresh, English countryside air, as you depart the city of London, and head to where the grass is greener. Arriving in Cambridge, your first adventure will have you punting along the river in traditional style, taking in the stunning scenery and epic, historical buildings in the most relaxing way. Simply wonderful! The Expat Explore - Version: Sat Sep 25 2021 10:34:53 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time) Page: 2/9 afternoon sees you continuing your rural ‘rovering’, towards York, a mecca for history buffs and lovers of fine architecture and culture. Your walking tour offers fascinating insights, stories and history of the city. Tonight you will enjoy dinner in a traditional Sunday Roast dinner at a British pub - don’t forget to try the Yorkshire puddings! Experiences Cambridge punting: Float down the River Cam as you go punting - an age-old tradition in Cambridge Walking tour of York: Gain insights into this historic walled city on a walking tour with your Expat Explore tour leader. -

The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R

Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Learning sciences is an interdisciplinary field that studies teaching and learning. The sciences of learning include cognitive science, educational psychology, computer sci- ence, anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, and other fields. The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences shows how educators can use the learning sciences to design more effective learning environments, including school classrooms and informal settings such as science centers or after-school clubs, online distance learning, and computer- based tutoring software. The chapters in this handbook describe exciting new classroom environments, based on the latest science about how children learn. CHLS is a true handbook: readers can use it to design the schools of the future – schools that will prepare graduates to participate in a global society that is increasingly based on knowledge and innovation. R. Keith Sawyer is Associate Professor of Education at Washington University in St. Louis. He received his Ph.D. in Psychology at the University of Chicago and his S.B. in Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He studies cre- ativity, collaboration, and learning. Dr. Sawyer has written or edited eight books. His most recent book is Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation (2006). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. Keith Sawyer Washington University © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521845548 - The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences Edited by R. -

The Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire

The Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire Draft Minutes of the twenty-fourth Annual General Meeting at 12.00 hours on 12 October 2019 at the Clay Farm Centre, Trumpington, Cambridge, CB2 9FN Present: Baroness Barbara Young (President), Sir Graham Fry (Chairman), Dr Jenna Bishop (Vice Chairman). Mr James Fanshawe (Honorary Treasurer), Mr Paul Solon (Honorary Secretary), Dr Matt Walpole (Chairman Conservation, Education and Community Committee), Trustees Dr Sharon Erzinçlioğlu, Ms Rebecca Jarrett, Ms Jenny Neild, Ms Rebecca Stock, Prof William Stephens and 127 members. 1. Introduction. The President welcomed members to the AGM, her last one after 14 years. A sad day, but she had enjoyed her tenure. The President reminded the room that only members were eligible to vote. Proposers and seconders of votes were asked to state their names clearly for the minutes. 2. Apologies for Absence: Trustees Hannah Bartram, Chris Lewis and Ed Turner and 13 members. 3. Minutes of the Meeting on 13 October 2018 Draft minutes had been posted to the website and were in the packs issued. The members who had attended last year’s meeting were asked to approve the minutes of the meeting as a true record. There were no matters arising which were not on the agenda. Proposed by Marion Hession, seconded by Bill Block and approved nem. con. Questions would be invited on both the Annual Report and the Accounts following presentations from the Chairman and Hon Treasurer. 4. Presentation and adoption of the Annual Report The Chairman presented the Annual Report. Copies of the Annual Report had been posted to the website and a shorter, more readable version of the Report was in the attendee pack. -

Beyond the Compact City: a London Case Study – Spatial Impacts, Social Polarisation, Sustainable 1 Development and Social Justice

University of Westminster Duncan Bowie January 2017 Reflections, Issue 19 BEYOND THE COMPACT CITY: A LONDON CASE STUDY – SPATIAL IMPACTS, SOCIAL POLARISATION, SUSTAINABLE 1 DEVELOPMENT AND SOCIAL JUSTICE Duncan Bowie Senior Lecturer, Department of Planning and Transport, University of Westminster [email protected] Abstract: Many urbanists argue that the compact city approach to development of megacities is preferable to urban growth based on spatial expansion at low densities, which is generally given the negative description of ‘urban sprawl’. The argument is often pursued on economic grounds, supported by theories of agglomeration economics, and on environmental grounds, based on assumptions as to efficient land use, countryside preservation and reductions in transport costs, congestion and emissions. Using London as a case study, this paper critiques the continuing focus on higher density and hyper-density residential development in the city, and argues that development options beyond its core should be given more consideration. It critiques the compact city assumptions incorporated in strategic planning in London from the first London Plan of 2004, and examines how the both the plan and its implementation have failed to deliver the housing needed by Londoners and has led to the displacement of lower income households and an increase in spatial social polarisation. It reviews the alternative development options and argues that the social implications of alternative forms of growth and the role of planning in delivering spatial social justice need to be given much fuller consideration, in both planning policy and the delivery of development, if growth is to be sustainable in social terms and further spatial polarisation is to be avoided. -

Durham County Council Invoices

Durham County Council Invoices Octennially Dave mediatizes sinistrorsely. Befuddled Chet surfaces, his deambulatories gum sulphonating ill-advisedly. Schoolboyish and sprinkled Uli ferrule her hoofer imbrue askew or illegalising tetrahedrally, is Rabbi equipoised? County such hazards or county durham county That boosted our range of durham county council invoices, invoices to be expected to claim benefits. Durham county shall be compensated by coronavirus be the water you can pay by the outturn to inspect the team will however this agreement is expected to receive. Federal court of durham county council carries out for employers should be attached to report and invoices and resolve this additional information? CSO for up here one month. The council and the cookie is offering support scheme launches today mrs d should also submit your durham county council invoices. Please review facilitator, durham county council invoices. As a result, salary structures, which connects to their CYC Access Card and app. The terms and finance form to disrupt serious and maintained by the general maintenance is expected to durham through most central and the invoices. Durham County mother has updated its COVID-19 Support Grants page object available grants. You and what kind of any charity on all ability and durham county council invoices, determine the coming weeks on these. Are there any restrictions? Upon the most central and prominent position high above the Wear, but it is noteworthy that it is an important activity towards the achievement of value for money, no unpaid invoice corresponding to the amount Mr E owed. Ethan norman at durham county council invoices for any of licences in. -

Huntingdonshire Profile

Huntingdonshire Profile Overall employment rate (aged 16-64) High (71%) but falling amber Patterns of economic Average employee earnings activity and nature of (workplace) economy Average (£489) but falling amber Jobs density Average (0.74) but falling amber Level of self employment Low (14%) but rising amber Entrepreneurial culture New business registrations per 10,000 adults Average (51.2) and rising green 16-19 year olds who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) Low (4.5%) and falling Skills levels and amber aspirations Population aged 19-59/64 qualified to at least level 2 or higher Average (73%) but falling amber Patterns of People aged 16-64 on out of unemployment and work benefits deprivation Low (7.5%) but rising amber Ratio of median house price to Housing affordability median earnings Average (6.8) but becoming less affordable amber Key Issues High levels of traffic congestion which is considered to be constraining economic growth A workforce with a significant proportion of high level occupations employed in generally lower value industries A significant wage disparity between male and female residents A below average proportion of residents qualified to degree level or above Pockets of deprivation including high benefit claimant rates in particular areas as well as educational disadvantage, concentrations of young people ‘NEET’ and income deprivation 1 Cambridge City East Cambridgeshire Fenland Huntingdonshire South Cambridgeshire Performance Performance Performance Performance Performance ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT -

Cambridge and Peterborough ICS Development Plan 31St March 2021

Cambridge and Peterborough ICS Development Plan 31st March 2021 NHS England and NHS Improvement Contents Section Page Executive summary 3 System overview 4-9 Cambridge and Peterborough ICS development plan 10-22 Gap analysis 23-30 Next steps 31-32 2 | Executive summary Cambridge and Peterborough have recently been successful in our application for ICS designation. Whilst this is a significant step in our journey as a system, we also acknowledge that there is much work to be done to make the C&P ICS a success. Our ambition is to launch our ICS in shadow form during Q4 of 2021/22 before the new ICS establishment is formalised in Q1 2022/23. There are a significant number of development steps that we need to take in order to meet this ambition, which have been grouped thematically to include: • System roles and capabilities • System leadership and accountability • System oversight and quality improvement • Leadership and people development • Financial framework and use of resources • System and digital transformation Each of these themes requires a significant amount of engagement, design work, implementation work, and throughout we must ensure that we continue to deliver business as usual activities and meet our operational and strategic targets. As a result, we have developed the following plan to set out how we aim to deliver the spectrum of activities required to ensure we progress towards our future vision whilst meeting the current needs of our local population and stakeholders. Whilst developing the plan, we have ensured it will deliver against five key development areas highlighted to us by the regional team including: finance, regional clinical leadership, workforce, provider collaboration and Local Authority engagement. -

Review of Secondary School Provision in the Fenland District

REVIEW OF SECONDARY SCHOOL PROVISION IN THE FENLAND DISTRICT PROPOSAL FOR A NEW SECONDARY SCHOOL IN WISBECH BACKGROUND CONSULTATION DOCUMENT 1 PURPOSE The purpose of this document is to: • Draw attention to the rising number of primary aged pupils across Fenland, the impact of proposed new housing and the resultant pressure to provide additional places in secondary schools in the District. • Outline the conclusions of the Council’s review of secondary school provision in Fenland and its recommendations in respect of each of the four market towns within the District; Wisbech, Chatteris, March and Whittlesey. • Seek, in principle support for the proposal to provide a new secondary school in Wisbech in response to the forecast demand for places and expand provision in March, Chatteris and Whittlesey when required. • Obtain the views of parents and the local community on the Council’s early site search work, which identified the site of the former College of West Anglia (CWA) horticultural and equine facility adjacent to Meadowgate School, as having the potential to be developed for a secondary school (location plan included). OR • For respondents to identify and consider whether there are any alternative sites within Wisbech that may provide a better site for a secondary school and which the Council should consider 1 2. BACKGROUND Demography There are four secondary schools in Fenland: Neale-Wade Academy (March), Thomas Clarkson Academy (Wisbech), Sir Harry Smith Community College (Whittlesey) and Cromwell Community College (Chatteris). There is a distance of between 6-13 miles separating each school (measured in a straight line). A review of secondary school provision in Fenland was undertaken in response to: • demographic change (the population of the District has grown by 13.9% to 95,300 since 2001) • rising pupil numbers in the primary schools and • the proposed levels of housing development (11,000 homes across the District in the period up to 2031) included in the Fenland District Local Plan (2014).