The Financial Crisis: a Parable Xi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

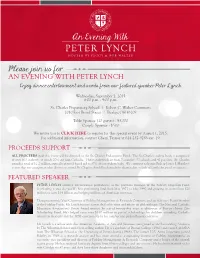

Please Join Us for an EVENING with PETER LYNCH Enjoy Dinner, Entertainment and Words from Our Featured Speaker, Peter Lynch

Please join us for AN EVENING WITH PETER LYNCH Enjoy dinner, entertainment and words from our featured speaker, Peter Lynch. Wednesday, September 2, 2015 6:00 p.m. - 9:00 p.m. St. Charles Preparatory School | Robert C. Walter Commons 2010 East Broad Street | Bexley, OH 43209 Table Sponsor (10 guests) - $5,000 Couple Sponsor - $500 We invite you to CLICK HERE to register for this special event by August 1, 2015. For additional information, contact Cherri Taynor at 614-252-9288 ext. 19. PROCEEDS SUPPORT ALL PROCEEDS from this event will be directed to the St. Charles Endowment Fund. The St. Charles student body is comprised of over 600 students, of which 20% are non-Catholic. These students draw from 7 counties, 53 schools and 42 parishes. St. Charles awards a total of $1.2 million annually in need-based aid to 37% of our student body. We continue to honor Bishop James J. Hartley’s vision that no young man who desires to attend St. Charles should be denied the chance due to lack of family financial resources. FEATURED SPEAKER PETER LYNCH attained international prominence as the portfolio manager of the Fidelity Magellan Fund, developing it into the world’s best performing fund from May 1977 to May 1990 and growing its assets from $20 million to over $14 billion and helping millions of American investors. Though currently Vice Chairman of Fidelity Management & Research Company and an Advisory Board Member of the Fidelity Funds, Mr. Lynch focuses a great deal of his time and efforts on philanthropy. The National Catholic Education Association’s Seton Award winner, he served twenty-five years as chairman of Boston’s Inner City Scholarship Fund. -

Our Firm and Fidelity. Working Together for You. Helping to Serve Your Best Interests

Our Firm and Fidelity. Working Together for You. Helping to serve your best interests. 31822.indd A 9/20/07 10:52:30 AM 331822.indd1822.indd B 99/12/07/12/07 11:56:14:56:14 PPMM A powerful combination As your financial advisor, we’re expected to make decisions about your money based on the highest degree of scrutiny. You can be assured that we use the same approach when choosing the service providers we employ to help meet your financial objectives. This is why we’ve selected Fidelity Investments as our custodian. What is a custodian? A custodian is a financial institution that has legal responsibility for a customer’s securities. Custodianship includes management as well as safekeeping, and this service incurs additional fees. Our firm, like all investment managers, is required to have a custodian. Investments that you entrust to our firm are placed in custody with Fidelity’s clearing firm, National Financial Services LLC (NFS) — one of the largest clearing providers in the industry. A clearing firm is an organization that works with financial exchanges to handle the confirmation, delivery, and settlement of transactions. When you’re selecting your financial advisor, it can be a critical factor to consider who your advisor uses to custody your investments, as this will help to determine the level of service, support, and protection that you can expect from your financial advisor. OUR FIRM AND FIDELITY 1 331822.indd1822.indd C 99/20/07/20/07 33:06:50:06:50 PPMM How does our relationship with Fidelity benefit you? An experienced, reputable firm helping to (SIPC). -

Ebook Download the Little Book of Stock Market Cycles Ebook Free Download

THE LITTLE BOOK OF STOCK MARKET CYCLES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jeffrey A. Hirsch,Douglas A. Kass | 240 pages | 07 Sep 2012 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118270110 | English | New York, United States The Little Book of Stock Market Cycles PDF Book KO , Lowe's Companies Inc. Fearing that they will lose all of their investment, they hastily sell their shares, often at a loss. The author of another great investment book, "Beating the Street," Peter Lynch's "One Up On Wall Street" is a go-to for investors who want to draw on their own common sense and knowledge to make smart investments. Investing in the Market. Morgan Stanley. In general, they believe that price increases and profit margin expansion are likely to decelerate, given a decline in commodity prices. We only partner with companies we believe offer the best products and services for small business owners. What method do you use to place your stop? Compare Accounts. One of the most common mistakes in stock market investing is trying to time the market. Receive full access to our market insights, commentary, newsletters, breaking news alerts, and more. Nicole Dieker Posts. The Stock Market and Your Life. The second type is the index tracking fund, which typically has lower costs and is more effective in matching the growth of the stock market. Financial Ratios. We sometimes make money from our advertising partners when a reader clicks on a link, fills out a form or application, or purchases a product or service. Her expertise is featured throughout Fit Small Business in personal finance , credit card , and real estate investing content. -

Learn from Investing Legends for 2020 & Beyond

Learn from Investing Legends for 2020 & Beyond Investors can learn a tremendous amount from studying philosophies and disclosed strategies of great investors. presented by Justin Carbonneau of Validea The Big Idea 163 Words Holding individual stocks remains a vital piece of long-term wealth creation. Sourcing and analyzing specific ideas, however, can be time-consuming, risky & complicated. With over 15,000 stocks, mutual funds and ETFs in the U.S. alone, you could spend a lifetime analyzing the set of investable ideas. In today's fast-paced world, many people lack the time to even sit down for dinner, so finding sound, efficient methods for stock analysis and idea generation is essential for today’s active stock investor. So, how do you effectively and systematically identify and research good opportunities? We believe proven, time-tested methodologies from legendary investors like Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch, Ben Graham and others with demonstrable approaches extracted from publicly disclosed writings provide a useful framework for sourcing and analyzing stocks that can play an important role in long-term wealth accumulation. The following presentation is dedicated to how we leverage and emulate these strategies to find sound investments ideas and what active investors like yourself can learn from them. Today’s Presentation • Opening insights from a legendary stock-picker; • Identification of the Gurus/Strategies; • Who are the Gurus/Strategies; • An overview of 5 different strategies – evidence, strategy & investment thesis behind each for today’s environment and the active fundamental investor; • Detailed investment methodologies & stock specific examples; • Key lessons and other tips to help the stock selection process; • Q&A Recent Thoughts on Stock-Picking from Market Master, Peter Lynch Barron’s, Dec. -

Seek to Enhance Returns Manage Risk Focused Outcomes

FACTOR INVESTING: Targeting your investment needs Seek to enhance returns Manage risk Focused outcomes 1 Table of Contents • Introduction • What is factor investing? • How to use factors in a portfolio • Fidelity Factor ETFs • Tools and resources 2 The 1980’s 17% Source: Morningstar, Average Annualized Return S&P 500 Index January 1st 1980 to December 31, 1989 3 The 1990’s 18% Source: Morningstar, Average Annualized Return S&P 500 Index January 1st 1990 to December 31, 1999 4 The 2000’s -1% Source: Morningstar, Average Annualized Return S&P 500 Index January 1st 2000 to December 31, 2009 5 The first half of the 2010’s 13% Source: Morningstar, Average Annualized Return S&P 500 Index January 1st 2010 to December 31, 2015 6 Low Growth Environment OVER THE NEXT 20 YEARS: • Global growth is expected to be somewhat slower due primarily to deteriorating demographics in most countries, with developing economies likely to register the highest growth rates. • We forecast U.S. GDP growth of 1.586% over the next 20 years, compared with a forecast of 2.1% for global GDP growth for the same time frame. REAL GDP GROWTH, 2016-2035 6.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 U.S. Growth Rate = 1.586% 1.0 0.0 Italy U.K. U.S. Peru India Brazil Spain China Japan Russia Turkey France Mexico Canada Sweden Thailand Australia Malaysia Germany Colombia Indonesia Philippines Netherlands South Africa South Korea Source: Fidelity Investments (AART) as of Dec. 31, 2015. 7 Dilemma for investors • Historical returns tell us that nothing is certain in the equity markets • Traditional investing -

The Toll of Being the Best

ON THE HORIZON HISTORY LESSONS The Toll of Being the Best BY GLENN RIFKIN he only thing more startling than Peter Investment wizard Lynch’s run on Wall Street may have been Peter Lynch’s remarkable run his decisionT to walk away. It was 1990, the height of the bull run only demanded more. on Wall Street, and at the age of 46, the man who had built the most successful mutual fund in mate, inducing one of every 100 to Marcus, as his success grew, so the world decided to call it quits. Americans to invest in Magellan. did the freedom Fidelity gave him In doing so, he made it clear that Fidelity, for its part, saw its to be bolder and make bigger bets success for any leader can also fortunes soar, from assets of $4.8 inside the Magellan portfolio. have its burdens. billion to more than $114 billion, Many thought Lynch’s genius For those under 40, the name as it helped convince millions of at identifying companies whose might not ring a bell. But Lynch’s Americans that the stock market stock was poised to skyrocket bespectacled, white-haired could carve a path to retirement. was all about following his gut. image, so prevalent “His perfor- In fact, his success was fueled by on cable business mance was really a yeoman’s appetite for research channels in the ’80s, How extraordinary,” and analysis of every company might. A fund man- He Changed said Alan Marcus, a whose stock he acquired. ager at a time when the Game professor of finance Still, Lynch’s decision to retire mutual funds were at Boston College’s at such a young age shocked not yet on the radar Carroll School of Fidelity and the investment com- % of most individual 29 Management. -

Adaptive Investment Approach

WhatResearch a CAIA Member Review Should Know What a CAIA Member Should Know CAIAWhatCAIA Membera Member CAIA Member Contribution Contribution Should Know Adaptive Investment Approach Henry Ma Founder and Chief Investment Officer, Julex Capital 8 Alternative Investment Analyst Review Adaptive Investment Approach Adaptive Investment Approach What a CAIA Member Should Know What a CAIA Member Should Know During the last decade, we have experienced two deep it does not follow any particular benchmark. Adaptive bear markets as results of the Internet bubble burst and investment is similar to tactical asset allocation (TAA) the subprime mortgage crisis. Many investors lost sig- or global macro. TAA normally under/over-weights nificant amounts of their wealth, and as a result, some certain asset classes relative to its strategic targets. The of them had to put their retirement plans on hold. The TAA managers normally make tactical decision main- traditional investment theory such as mean-variance ly based on their return forecasts. There is no need to (MV) portfolio theory, the efficient market hypothesis forecast returns with the adaptive investment approach. (EMH), and associated practices such as buy-and-hold, A global macro strategy typically allocates capital to or benchmark-centric investments have proven inad- undervalued asset classes and shorts overvalued asset equate in helping investors to achieve their financial classes. In addition, it employs leverage to enhance re- goals. Market participants are now questioning these turns based on the managers’ views. The adaptive in- broad theoretical frameworks and looking for alterna- vestment approach is a long-only strategy. In addition, tive ways to make better investment decisions. -

Fidelity Vs. Vanguard WHICH FUNDS ARE BEST for YOU?

SPECIAL REPORT Fidelity vs. Vanguard WHICH FUNDS ARE BEST FOR YOU? Fidelity vs. Vanguard. Magellan vs. 500 Index. Ned Johnson vs. Jack Bogle. Active vs. Passive Investing. The hidden pitfalls and profit potential of both … and what difference could it make to you? We’ve spent more than 20 years specializing in both Fidelity and Vanguard mutual funds, and that gives us the experience and perspective to compare the two companies’ funds and managers, strengths and weaknesses, pit- falls and profit potential. We’ve learned over years of managing money for hun- The answer depends on you and your investment goals. dreds of clients like you that there is no simple, one-size There’s no reason you can’t have accounts with both fits-all answer. Both companies have done an outstanding Fidelity and Vanguard (among others). You’ll have two (or job delivering long-term value to shareholders—albeit more) sets of statements to review, multiple phone num- with distinctly different philosophies. In fact, we believe bers to remember, several websites to navigate, and more that investors who focus on the question of “Who’s big- than 650 funds to understand and monitor. It’s a major gest?” or “Who’s best?” miss a more important point: undertaking, no doubt, but far from impossible. It’s not a matter of which fund company is better. It’s But there is a benefit to consolidating: Savings and a matter of which company’s funds serve your individual simplicity. needs best. Sure you can get used to reviewing multiple sets of In this report we will provide you with the information statements each month, but you have to ask yourself what you need to make an informed decision for yourself. -

New Evidence from a Bootstrap Analysis

Can Mutual Fund \Stars" Really Pick Stocks? New Evidence from a Bootstrap Analysis Robert Kosowski, Allan Timmermann, Russ Wermers, and Hal White* September 2005 Can Mutual Fund \Stars" Really Pick Stocks? New Evidence from a Bootstrap Analysis Abstract We apply a new bootstrap statistical technique to examine the performance of the U.S. open-end, domestic-equity mutual fund industry over the 1975 to 2002 period. This bootstrap approach is nec- essary because the cross-section of mutual fund alphas has a complex, non-normal distribution{due to heterogeneous risk-taking by funds as well as non-normalities in individual fund alpha distrib- utions. Our bootstrap approach reveals ndings that di er from many past studies. Speci cally, we nd that a sizable minority of managers pick stocks well enough to more than cover their costs; moreover, the superior alphas of these managers persist. Was Peter Lynch, former manager of the Fidelity Magellan fund, a \star" stockpicker, or was he simply endowed with stellar luck? The popular press seems to assume that his fund performed well due to his unusual acumen in nding underpriced stocks. In addition, Marcus (1990) asserts that the prolonged superior performance of the Magellan fund is dicult to explain as a purely random outcome, where one assumes that Mr. Lynch and the other Magellan managers have no true stockpicking skills, and are merely the luckiest of a large group of fund managers. More recently, the Schroder Ultra Fund topped the eld of 6,000 funds (across all investment objective categories) with a return of 107 percent per year over the three years ending in 2001{and closed to new investors in 1998 due to overwhelming demand, presumably because investors credited the fund manager with having extraordinary skills. -

Personal Trading by Mutual Fund Managers

Washington University Law Review Volume 73 Issue 4 January 1995 Foxes and Hen Houses?: Personal Trading by Mutual Fund Managers Edward B. Rock University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Recommended Citation Edward B. Rock, Foxes and Hen Houses?: Personal Trading by Mutual Fund Managers, 73 WASH. U. L. Q. 1601 (1995). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol73/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXES AND HEN HOUSES?: PERSONAL TRADING BY MUTUAL FUND MANAGERS EDWARD B. ROCK* INTRODUCTION America's money is managed by professionals.' In this "fourth stage of capitalism,"' ensuring that those who manage our money do so in our interests becomes the critical question. This Article examines that question by focusing on the regulation of the personal trading activities of the managers of tomorrow's dominant institutional investor, mutual funds. Institutional investors are a varied group-public and private pension funds, life insurance companies, commercial bank trust departments, charitable trusts and mutual funds. An unanticipated consequence of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act's ("ERISA") full funding requirement," only now becoming clear, is that mutual funds are and will continue growing at the expense of traditional pension funds.4 ERISA's requirement that pension liabilities be fully funded has had the effect of driving money away from traditional defined benefit pension plans6 * Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania Law School. -

The Investor's Guide to Fidelity Funds

The Investor's Guide to Fidelity Funds Winning Strategies for Mutual Fund Investing Peter G. Martin M.Sc. (Applied Physics), Durham, U.K. and Byron B. McCann M.B.A. (Finance), Stanford Second Printing Venture Catalyst Redmond, Washington To America, for fostering the best investment climate in the world; and Japan, for reminding us of the importance of saving. To Fidelity Investments, for the mutual fund innovations that have revolutionized individual investing. To our families, for putting up with so much for so long. Copyright 1998 by Venture Catalyst, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work beyond that permitted by Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copy- right Act without the permission of the copyright owner is unlawful. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to Venture Catalyst Inc., 17525 NE 40th Street, Suite E123, Redmond WA 98052. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authori- tative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. From a Declara- tion of Principles jointly adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers. Publisher's Cataloging in Publication Data Martin, Peter G. and McCann, Byron B. The Investor's Guide to Fidelity Funds p. cm. Bibliography: p Includes index ISBN 1-881983-03-X 1. Mutual fundsÐUnited States. -

Annual March 31, 2001

TWEEDY, BROWNE GLOBAL VALUE FUND ANNUAL MARCH 31, 2001 TWEEDY, BROWNE AMERICAN VALUE FUND Tweedy, Browne Fund Inc. Investment Adviser’s Report . 1 Appendix A — Morningstar.com’s Ask the Analyst. 16 Appendix B — Value Investing and Behavioral Finance Speech . 34 Tweedy, Browne Global Value Fund: Portfolio Highlights . 51 Perspective on Assessing Investment Results . 52 Portfolio of Investments . 54 Schedule of Forward Exchange Contracts. 62 Statement of Assets and Liabilities. 67 Statement of Operations . 68 Statements of Changes in Net Assets. 69 Financial Highlights. 70 Notes to Financial Statements . 71 Investment in the Fund by the Investment Adviser and Related Parties . 75 Report of Ernst & Young LLP, Independent Auditors . 78 Tax Information (unaudited) . 79 Tweedy, Browne American Value Fund: Portfolio Highlights . 80 Perspective on Assessing Investment Results . 81 Portfolio of Investments . 83 Schedule of Forward Exchange Contracts. 88 Statement of Assets and Liabilities. 90 Statement of Operations . 91 Statements of Changes in Net Assets. 92 Financial Highlights. 93 Notes to Financial Statements . 94 Investment in the Fund by the Investment Adviser and Related Parties . 98 Report of Ernst & Young LLP, Independent Auditors. 101 Tax Information (unaudited) . 102 This report is for the information of the shareholders of Tweedy, Browne Fund Inc. Its use in connection with any offering of the Company’s shares is authorized only in a case of a concurrent or prior delivery of the Company’s current prospectus. Investors should refer to the accompanying prospectus for description of risk factors associated with investments in securities held by both Funds. Additionally, investing in foreign securities involves eco- nomic and political considerations not typically found in U.S.