Exploring Symbolism in Masstige Brand Advertising Within the Discursive Context of Luxury: a Semiotic Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Taís De F. Saldanha Iensen TRABALHO FINAL DE GRADUAÇÃO II O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRI

Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen TRABALHO FINAL DE GRADUAÇÃO II O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW Santa Maria, RS 2014/1 Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW Trabalho Final de Graduação II (TFG II) apresentado ao Curso de Publicidade e Propaganda, Área de Ciências Sociais, do Centro Universitário Franciscano – Unifra, como requisito para conclusão de curso. Orientadora: Prof.ª Me. Morgana Hamester Santa Maria, RS 2014/1 2 Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW _________________________________________________ Profª Me. Morgana Hamester (UNIFRA) _________________________________________________ Prof Me. Carlos Alberto Badke (UNIFRA) _________________________________________________ Profª Claudia Souto (UNIFRA) 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Inicialmente gostaria de agradecer aos meus pais por terem me proporcionado todas as chances possíveis e impossíveis para que eu tivesse acesso ao ensino superior que eles nunca tiveram, meus irmãos por terem me aguentado e me ajudado durante esse tempo, meus tios e tias, que da mesma forma que meus pais, sempre me incentivaram a estudar, meus avós que sempre me ajudarem nos momentos difíceis com sua sabedoria e experiência. Gostaria também de agradecer em especial à tia Edi, minha dinda, minha madrinha de coração que junto com meus pais, sempre me deu todo tipo de apoio para que eu não desistisse, mesmo nos momentos mais difíceis. Meu amigo Rafa que me deu a ideia do tema e ter me ajudado até a finalização do mesmo. -

Renee J. Vaca __ Department Head Hair Stylist Contact: Journeyman Local 706 (626) 379-2610 Feature Films & Television [email protected]

Renee J. Vaca __ Department Head Hair Stylist Contact: Journeyman Local 706 (626) 379-2610 Feature Films & Television [email protected] Dirty John/Betty Broaderick Department Head Amanda Peet NBC/USA Network Cast Gone Hollywood Department Head John Magaro FX/Pilot Nikolaj Coster-Waldau Lola Kirke Jonathan Pryce Strange Angel Department Head Jack Reynor CBS/Episodic (Episodes 5 & 6) Bella Heathcote Will & Grace Assistant Department Head Megan Mullally NBC/Sitcom Alec Baldwin Bobby Cannavale Dancing with the Stars Main Trailer Stylist Jenna Johnson ABC/Audience Reality Emmy Nominated Peta Murgatroyd Seasons 21-27 Jodie Sweetin Young & Hungry, Seasons 1-5 Department Head Emily Osment ABC Family/Sitcom Jonathan Sadowski Rex Lee Past Forward Department Head Hair Freida Pinto David O. Russell/Prada Guild Nominated Zachary Levi Dr. Strange Dept. Head US/Re-Shoots Mads Mikkelsen Marvel/Feature (US/Film Crew) Benedict Wong Nissan/Star Wars Department Head All Actors Commercial Mad Dogs Department Head Steve Zahn Amazon/Episodic Michael Imperioli Ben Chaplin Sean Saves The World Department Head, Hair Sean Hayes NBC/Sitcom Sami Isler Thomas Lennon Ground Floor Department Head Briga Heelan TBS/Sitcom Seasons 1 & 2 Skylar Astin John C. McGinley American Hustle Assistant Department Head Elisabeth Rohm David O. Russell/Feature Film Shea Whigham Michael Peña Page 1 of 3 Renee J. Vaca __ Feature Films & Television (continued) Revenge Department Head Emily VanCamp ABC/Episodic Josh Bowman Paranormal Activity 4 Department Head Kathryn Love Newton Paramount/Feature -

Berlino, 20 Novembre 2008

COMUNICATO STAMPA Berlino, 20 novembre 2008 - L’edizione 2009 del Calendario Pirelli, oggetto di culto da oltre 40 anni per gli amanti della fotografia, della bellezza e dell’evoluzione del costume, è stata presentata oggi in anteprima mondiale a Berlino presso “The Station”, l’antica stazione ferroviaria che a fine ‘800 collegava la capitale con Dresda ,Vienna e Praga. La cornice del 36simo “The Cal” sono i paesaggi del Botswana, dove nel maggio scorso il celebre fotografo Peter Beard ha immortalato per dieci giorni sette modelle di fama internazionale. Beard, che ha vissuto in Kenya per trent’anni, è uno dei più grandi interpreti mondiali del mistero e del fascino dell’Africa. Dopo la Cina, illustrata da Patrick Demarchelier accostando le atmosfere delle antiche case da tè alla modernità delle metropoli d'Oriente, il Calendario Pirelli si sposta in uno dei pochi luoghi dell’Africa ancora incontaminati e selvaggi, non tormentati dalle guerre e con la più alta concentrazione di animali. L’occhio di Peter Beard ha scelto una terra autentica e ancestrale, che nasce dalla contrapposizione tra due mondi diversi: l’oasi acquatica del delta dell’Okavango e la distesa arida e sabbiosa del deserto del Kalahari. Un luogo che nel tempo non ha subito lo sfruttamento del territorio né l’impoverimento delle risorse, nel quale l’autore ha voluto rappresentare la Natura come entità metafisica sempre in movimento, fonte di infinita creatività, entro i cui ritmi e le cui leggi ogni cosa deve avere inizio e fine. Una Natura descritta come possente e al tempo stesso ferita, con una visione armonica dell’ambiente che si richiama al filone naturalistico statunitense del XIX secolo. -

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny: A Feminist Analysis of a Fashion Trend Rosa Crepax Goldsmiths, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Sociology May 2016 1 I confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Rosa Crepax Acknowledgements I would like to thank Bev Skeggs for making me fall in love with sociology as an undergraduate student, for supervising my MA dissertation and encouraging me to pursue a PhD. For her illuminating guidance over the years, her infectious enthusiasm and the constant inspiration. Beckie Coleman for her ongoing intellectual and moral support, all the suggestions, advice and the many invaluable insights. Nirmal Puwar, my upgrade examiner, for the helpful feedback. All the women who participated in my fieldwork for their time, patience and interest. Francesca Mazzucchi for joining me during my fieldwork and helping me shape my methodology. Silvia Pezzati for always providing me with sunshine. Laura Martinelli for always being there when I needed, and Martina Galli, Laura Satta and Miriam Barbato for their friendship, despite the distance. My family, and, in particular, my mum for the support and the unpaid editorial services. And finally, Goldsmiths and everyone I met there for creating an engaging and stimulating environment. Thank you. Abstract Since 2010, androgyny has entered the mainstream to become one of the most widespread trends in Western fashion. Contemporary androgynous fashion is generally regarded as giving a new positive visibility to alternative identities, and signalling their wider acceptance. But what is its significance for our understanding of gender relations and living configurations of gender and sexuality? And how does it affect ordinary people's relationship with style in everyday life? Combining feminist theory and an aesthetics that contrasts Kantian notions of beauty to bridge matters of ideology and affect, my research investigates the sociological implications of this phenomenon. -

Marcas E Editoriais De Moda Em Diferentes Nichos De Revistas Especializadas

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Engenharia Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas O caso Vogue, i-D e Dazed & Confused Joana Miguel Ramires Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Design de Moda (2º ciclo de estudos) Orientador: Prof. Doutora Maria Madalena Rocha Pereira Covilhã, Outubro de 2012 Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas II Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas Agradecimentos Ao longo do percurso que resultou na realização deste trabalho, foram várias as pessoas que ajudaram a desenvolve-lo e que disponibilizaram o seu apoio e amizade. Desta forma, o primeiro agradecimento vai para a orientadora, Professora Doutora Maria Madalena Rocha Pereira, que desde o início foi incansável. Agradeço-lhe pela disponibilidade, compreensão, por me ter guiado da melhor forma por entre todas as dúvidas e problemas que foram surgindo, e por fim, pela força de vontade e entusiamo que me transmitiu. A todos os técnicos e colaboradores dos laboratórios e ateliês do departamento de engenharia têxtil da Universidade da Beira Interior agradeço o seu apoio e os ensinamentos transmitidos ao longo da minha vida académica. Agradeço em especial á D. Lucinda pela sua amizade, e pelo seu apoio constante ao longo destes anos. Às duas pessoas mais importantes da minha vida, pai e mãe agradeço do fundo do coração por todo o amor, carinho, compreensão, e por todos os sacrifícios que fizeram, de modo a me permitirem chegar ao final de mais esta etapa de estudos. Aos meus avós e restante família que também têm sido um pilar fundamental na minha vida a todos os níveis, os meus sinceros agradecimentos. -

PDF Download Carine Roitfeld

CARINE ROITFELD - IRREVERENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carine Roitfeld | 368 pages | 18 Oct 2011 | Rizzoli International Publications | 9780847833689 | English | New York, United States Carine Roitfeld - Irreverent PDF Book Send Report. I have always gone after the most interesting things, even if they are the most difficult. Rather than taking the time to dig through the internet, I can just go to Booking Agent Info and its all there for me. Primary Menu. Carine Roitfeld: Irreverent Hardcover. Carine Roitfeld: Irreverent Overview "Carine, and her vision of French Vogue, embodies all that the world likes to think of as Parisian style: a sense of chic that's impeccable and sometimes idiosyncratic and which forever lives on a moonlit street as seen through the lens of Helmut Newton. Courtney Rust courtneyrust. Resistant applications. Carine Roitfeld Agent Name:. The best products, from fashion to beauty to home, curated for you by Vogue's editors. Some played it safer than others — Kanye, we're looking at you — but Carine, Ciara, Anja Rubik, and lots more embraced the call to otherworldly glamour with capes, crimson lips, and in some cases, a hint of fake blood. This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. I do things by instinct. Can you define it, or is it a mystery to you? Hardcover Nonfiction Books. This page is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon. View On One Page. Amazon, the Amazon logo, Endless, and the Endless logo are trademarks of Amazon. -

In International Management the Replication Of

Master’s Degree programme Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) in International Management Final Thesis The Replication of Strategic Format as Internationalization Method Calzedonia Case Supervisor Ch. Prof. Vladi Finotto Graduand Federica Giarola Matriculation Number 855683 Academic Year 2016 / 2017 ABSTRACT Business organizations may expand internationally by replicating part of their value chain, such as products, prices, marketing and communication tools, organizational structures and stores design through the creation of a format. However, it is difficult for replicators to find the right format, to adjust it in order to adapt to local environments and to transfer knowledge abroad. To dicover these issues, I studied the organizational structure of Calzedonia, the firm leader of underwear apparel, involving interested offices with long interviews. I find that Calzedonia, after a period of exploration, proceeded in terms of replicating a format in a flexible manner, supporting an ongoing learning process aimed to adapt what is flexible to the market. The format, in fact, presents two fundamental characteristics: fixed features used everywhere without modifications and flexible ones able to adapt locally. Another finding is how Calzedonia uses the format in its internationalization strategy, through franchising network. I conclude the thesis with an overview of the future challenges just approached by the firm: US and China markets. 1 CONTENTS AKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................... -

1 United States District Court Southern

Case 1:20-cv-07255 Document 1 Filed 09/04/20 Page 1 of 87 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------X 20-cv-7255 ABBY CHAMPION, ALANNA ARRINGTON, AMBAR CRISTAL ZARZUELA MONTERO, ANNA CLEVELAND, ANOK YAI, BLANCA PADILLA, BRIONKA HALBERT, BROOKE ROBINSON, CALLUM STODDART, CARA TAYLOR, CLAIRE DELOZIER, CYNTHIA ARREBOLA, DAMIEN MEDINA, DYLAN CHRISTENSEN, EMILY REBECCA HILL p/k/a EMI RED, ENIOLA ABIORO, GEORGINA GRENVILLE, GRACE ELIZABETH HARRY CABE p/k/a GRACE ELIZABETH, GRACE HARTZEL, HIANDRA MARTINEZ, JAL BUI, JOÃO KNORR, KRISTIN LILJA SIGURDARDOTTIR p/k/a KRISTIN LILJA, LEONA WALTON p/k/a BINX WALTON, LINEISY MONTERO, LUCIA LOPEZ AYERDI p/k/a LUCIA LOPEZ, LUISANA GONZALEZ, MANUELA MILOQUI p/k/a MANU MILOQUI, MARIA VITORIA SILVA DE OLIVEIRA p/k/a MARIA VITORIA, MARIAM URUSHADZE p/k/a MARISHA URUSHADZE, MAUD HOEVELAKEN, MAYA GUNN, MYRTHE BOLT, RACHELLE HARRIS, ROCIO MARCONI, SARA EIRUD, SELENA FORREST, SHUPING LI, TANG HE, UGBAD ABDI p/k/a UGBAD, VERA VAN ERP, VIKTORIIA PAVLOVA p/k/a ODETTE PAVLOVA, XIAOQIAN XU, Plaintiffs, COMPLAINT -Against- JURY DEMAND MODA OPERANDI, INC., ADVANCE PUBLICATIONS, INC. d/b/a CONDE NAST, ADVANCE MAGAZINE PUBLISHERS, INC. d/b/a CONDE NAST Defendants, ------------------------------------------------------------------X All plaintiffs, by their attorneys, EDWARD C. GREENBERG, LLC, for their complaint allege as follows: THE PARTIES 1 Case 1:20-cv-07255 Document 1 Filed 09/04/20 Page 2 of 87 1. Plaintiff ABBY CHAMPION (“CHAMPION”) is a professional model who resides in Los Angeles California, and works as a professional model in the State and County of New York. -

Dolce & Gabbana's Communication and Branding Analysis

FACE Business Case Dolce & Gabbana’s Communication and Branding Analysis Il presente lavoro è stato redatto grazie al contributo degli studenti del corso di Laurea Magistrale in Fashion Communication: Cristiana Avolio, Federica Fancinelli, Valentina Foschi, Veronica Rimondi e Camilla Tosi 1 The work aims to analyze the communication strategies of Dolce&Gabbana, one of the most famous brands on a national and international level, that has been able to create, within a varied audience, a global strong recognition. The fashion company was founded in 1985 by two designers: Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana. 1. Zeitgeist and social context The inspiration of the designers Stefano Dolce and Domenico Gabbana comes from Sicily and the post-war neo-realist filmography, a land of perfumes and mysteries, a precious treasure chest of memories from which derive motifs destined to characterize each new collection. Surely their point of strength and recognition, both in lingerie and tailoring, is the black lace, a symbol of rigor and feminine sensuality; in fact the woman of Dolce & Gabbana, in balance between the modest and uninhibited, embodies the woman of our time with a strong and fragile personality at the same time, a concrete woman but also a dreamer. Protagonists of the fashion shows and the advertising campaigns are often the icon of the typical Italian beauty as: Bianca Balti, Monica Bellucci, Maria Grazia Cucinotta and Bianca Brandolini d'Adda. The Mediterranean woman becomes the point of reference and the muse of the two designers who highlight her shapes and her strong personality. For example, the bustier, as a synonymous for excellence of femininity that women, of all ages, have always used to outline and emphasize their bodies, recurs frequently in the brand pictures. -

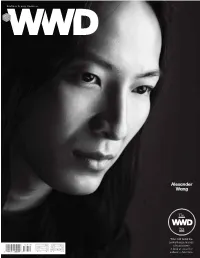

Alexander Wang

Fashion. Beauty. Business. APRIL 2015 No.1 Alexander Wang The Six Who will build the powerhouse brands US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1500 of tomorrow? CANADA $13 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG HK100 A look at six of the EUROPE € 11 INDIA 800 industry’s best bets. Fashion. Beauty. Business. APRIL 2015 No.1 The Row The Six Who will build the powerhouse brands US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1500 of tomorrow? CANADA $13 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG HK100 A look at six of the EUROPE € 11 INDIA 800 industry’s best bets. Christopher Kane J.W. Anderson Introducing the ricky drawstring 888.475.7674 ralphlauren.com The Ricky Sunglass ARMANI.COM/ATRIBUTE 800.929.Dior (3467) Dior.com © 2015 Estée Lauder Inc. © 2015 DRIVEN BY DESIRE esteelauder.com NEW. PURE COLOR ENVY SHINE On Carolyn: Empowered Sculpt. Hydrate. Illuminate. NEW ORIGINAL HIGH-IMPACT CREME AND NEW SHINE FINISH Contents Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Alexander J.W. Wang The Row Anderson Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Chitose Christopher Proenza Abe Kane Schouler Six Covers Photographer Nigel Parry shot the designers for the cover story during a whirlwind global tour. “To be asked to photograph the covers for the launch of the new WWD weekly is a gift to any photographer,” he said. “I’m not saying it was easy — eight designers, six days, three continents — but the jet-lag was kept at bay by meeting such great talents. Thank you WWD!” Cover Story The 168 Fashion has long been obsessed with the new, the fresh, the unexpected, never more so than now. -

Strategic Planning Online

Strategic Planning for the real world How to harness the wealth of information, inspiration and insight on the Internet for more resonant, relevant and effective communications Nicholine Hayward April 2009 ͞WĞƌŚĂƉƐLJou will seek out some trove of data and sift through it, balancing your intelligence and intuition to arrive at a glimmering new idea.͟ Steven D Levitt and Stephen J Dubner Freakonomics Introduction The problem with Planning is that we need to know what people want. This means asking them questions, which immediately creates a dilemma. Every group, every, omnibus, survey or depth interview, however carefully planned and objectively moderated, engenders a sense of self- consciousness in the respondents that can skew the results. tĞ͛ǀĞall been to Groups where someone was afraid to speak while another liked the sound of his own voice a bit too much. tŽƵůĚŶ͛ƚŝƚďĞŶŝĐĞƚŽďĞable to ƐĞĞǁŚĂƚǁĂƐŝŶƉĞŽƉůĞ͛ƐŚĞĂĚƐǁŝƚŚŽut having to ask? Would it be good to have data from a larger proportion of the population than the base sizes we normally have? tŝƚŚƚŚĞƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚŵĞƚŚŽĚŽůŽŐLJ/͛ŵĂďŽƵƚƚŽĚĞƐĐƌŝďĞ͕we can. By looking at what millions of people are asking for and talking about online, we have access to the largest, most honest and unself- conscious focus group in the world. We can apply the results of this methodology to every stage of a business and marketing strategy, from developing the products that people are looking for and improving the ones they are already buying, to devising communications campaigns that really strike a chord. We can use it to see market and category dynamics reflected in consumer awareness and demand, to find out what people think about a brand, create rounded and realistic pen portraits and a resonant tone of voice or to gain insights into consumer behaviour ʹ and how best to reach them.