The Strategic Balance of Israel's Withdrawal from Gaza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 459.71 Kb

מרכז המידע הישראלי לזכויות האדם בשטחים (ע.ר.) One Big Prison Freedom of Movement to and from the Gaza Strip on the Eve of the Disengagement Plan March 2005 Researched and written by Yehezkel Lein Data coordination by Najib Abu Rokaya, Ariana Baruch, Rim ‘Odeh, Shlomi Swissa Fieldwork by Musa Abu Hashhash, Iyad Haddad, Zaki Kahil, Karim Jubran, Mazen al-Majdalawi, ‘Abd al-Karim S’adi Assistance on legal issues by Yossi Wolfson Translated by Zvi Shulman, Shaul Vardi Edited by Rachel Greenspahn Introduction “The only thing missing in Gaza is a morning line-up,” said Abu Majid, who spent ten years in Israeli prisons, to Israeli journalist Amira Hass in 1996.1 This sarcastic comment expressed the frustration of Gaza residents that results from Israel’s rigid policy of closure on the Gaza Strip following the signing of the Oslo Agreements. The gap between the metaphor of the Gaza Strip as a prison and the reality in which Gazans live has rapidly shrunk since the outbreak of the intifada in September 2000 and the imposition of even harsher restrictions on movement. The shrinking of this gap is the subject of this report. Israel’s current policy on access into and out of the Gaza Strip developed gradually during the 1990s. The main component is the “general closure” that was imposed in 1993 on the Occupied Territories and has remained in effect ever since. Every Palestinian wanting to enter Israel, including those wanting to travel between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, needs an individual permit. In 1995, about the time of the Israeli military’s redeployment in the Gaza Strip pursuant to the Oslo Agreements, Israel built a perimeter fence, encircling the Gaza Strip and separating it from Israel. -

Gaza-Israel: the Legal and the Military View Transcript

Gaza-Israel: The Legal and the Military View Transcript Date: Wednesday, 7 October 2015 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 07 October 2015 Gaza-Israel: The Legal and Military View Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC General Sir Nick Parker For long enough commentators have usually assumed the Israel - Palestine armed conflict might be lawful, even if individual incidents on both sides attracted condemnation. But is that assumption right? May the conflict lack legality altogether, on one side or both? Have there been war crimes committed by both sides as many suggest? The 2014 Israeli – Gaza conflict (that lasted some 52 days and that was called 'Operation Protective Edge' by the Israeli Defence Force) allows a way to explore some of the underlying issues of the overall conflict. General Sir Nick Parker explains how he advised Geoffrey Nice to approach the conflict's legality and reality from a military point of view. Geoffrey Nice explains what conclusions he then reached. Were war crimes committed by either side? Introduction No human is on this earth as a volunteer; we are all created by an act of force, sometimes of violence just as the universe itself arrived by force. We do not leave the world voluntarily but often by the force of disease. As pressed men on earth we operate according to rules of nature – gravity, energy etc. – and the rules we make for ourselves but focus much attention on what to do when our rules are broken, less on how to save ourselves from ever breaking them. That thought certainly will feature in later lectures on prison and sex in this last year of my lectures as Gresham Professor of Law but is also central to this and the next lecture both on Israel and on parts of its continuing conflict with Gaza. -

As Israel's Political Parties Fight for Role of Kingmaker, Religious

Selected articles concerning Israel, published weekly by Suburban Orthodox Toras Chaim’s (Baltimore) Israel Action Committee Edited by Jerry Appelbaum ( [email protected] ) | Founding editor: Sheldon J. Berman Z”L Issue 8 8 1 Volume 2 1 , Number 1 2 Parshas Vayikra March 20 , 20 2 1 As Israel’s Political Parties Fight for Role of Kingmaker, Religious - Secular Divide Comes to the Fore By Haviv Rettig Gur timesofisrael.com March 15, 2021 Two very different parties have found in each other lawmakers and some Haredi party activists sharing p hotos the perfect enemies. of emaciated bodies being carried on wheelbarrows during Eight days to election day, the race between the pro - the Holocaust. and anti - Netanyahu camps is close. So close, in fact, that The video clip of that line went viral on Hebrew - neither side can hope to piece together an effective language social media. Few noticed the exchange that government. followed, in which Liberman went on to explain If Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu manages to something important about his campaign strategy — he eke out a slim majority, it will likely b e so slim that he will needs to boost support by driving secular voters to the find himself forced to cater to the whims of the most polls. right - wing lawmakers on the ballot. Netanyahu’s Challenged again by Asayag that he cannot push both opponents, meanwhile, theoretically led by Yair Lapid of Netanyahu and the Haredi parties out of government Yesh Atid, may well be too divided and diverse to produce simultaneously and will end up “hugging [Shas leader a manageable coa lition. -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research the Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research The Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies Evolution of settlement typologies in rural Israel Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of "Master of Science" By: Keren Shalev November, 2016 “Human settlements are a product of their community. They are the most truthful expression of a community’s structure, its expectations, dreams and achievements. A settlement is but a symbol of the community and the essence of its creation. ”D. Bar Or” ~ III ~ תקציר למשבר הדיור בישראל השלכות מרחיקות לכת הן על המרחב העירוני והן על המרחב הכפרי אשר עובר תהליכי עיור מואצים בעשורים האחרונים. ישובים כפריים כגון קיבוצים ומושבים אשר התבססו בעבר בעיקר על חקלאות, מאבדים מאופיים הכפרי ומייחודם המקורי ומקבלים צביון עירוני יותר. נופי המרחב הכפרי הישראלי נעלמים ומפנים מקום לשכונות הרחבה פרבריות סמי- עירוניות, בעוד זהותה ודמותה הייחודית של ישראל הכפרית משתנה ללא היכר. תופעת העיור המואץ משפיעה לא רק על נופים כפריים, אלא במידה רבה גם על מרחבים עירוניים המפתחים שכונות פרבריות עם בתים צמודי קרקע על מנת להתחרות בכוח המשיכה של ישובים כפריים ולמשוך משפחות צעירות חזקות. כתוצאה מכך, סובלים המרחבים העירוניים, הסמי עירוניים והכפריים מאובדן המבנה והזהות המקוריים שלהם והשוני ביניהם הולך ומיטשטש. על אף שהנושא מעלה לא מעט סוגיות תכנוניות חשובות ונחקר רבות בעולם, מעט מאד מחקר נעשה בנושא בישראל. מחקר מקומי אשר בוחן את תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי דרך ההיסטוריה והתרבות המקומית ולוקח בחשבון את התנאים המקומיים המשתנים, מאפשר התבוננות ואבחנה מדויקים יותר על ההשלכות מרחיקות הלכת. על מנת להתגבר על הבסיס המחקרי הדל בנושא, המחקר הנוכחי החל בבניית בסיס נתונים רחב של 84 ישובים כפריים (קיבוצים, מושבים וישובים קהילתיים( ומצייר תמונה כללית על תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי ומאפייניה. -

Subterranean Warfare: a New-Old Challenge

Subterranean Warfare: A New-Old Challenge Yiftah S. Shapir and Gal Perel Subterranean warfare is not new in human history. Tunnels, which have been dug in all periods for various purposes, have usually been the weapon of the weak against the strong and used for concealment. The time required to dig tunnels means that they can be an important tool for local residents against an enemy army unfamiliar with the terrain. Tunnels used for concealment purposes (defensive tunnels) can be distinguished from tunnels used as a route for moving from one place to another. The latter include smuggling tunnels used to smuggle goods past borders (as in the Gaza Strip), escape routes from prisons or detention camps, offensive tunnels to move forces behind enemy lines, and booby-trapped tunnels planted with explosives !"#$%#!#&'%()*+,+-+#.%/)%-)*-+*% .#"%0'%1)&).23 Operation Protective Edge sharpened awareness of the strategic threat posed by subterranean warfare. The IDF encountered the tunnel threat long ago, and took action to attempt to cope with this threat, but the scope of -4#%54#!6&#!6!7%).%0#*)&#%)55)$#!-%+!%8 ,'9: ; .-%<=>?7%@).%56$-$)'#"% as a strategic shock, if not a complete surprise, requiring comprehensive reorganization to handle the problem. Some critics argued that an investigative commission was necessary to search for the roots of the failure and punish those to blame for it. This article will review subterranean warfare before and during Operation Protective Edge, and will assess the strategic effects of this mode of warfare. !"#$%&#'()#*+,-"../0"/0#1/.2/." A 0-#$$)!#)!%@)$()$#%4).%)55#)$#"%&)!'%-+&#.%+!%-4#%:$)09B.$)#,+%*6!-#C-7% and the IDF and the Ministry of Defense have dealt with various aspects of the phenomenon of subterranean warfare for many years. -

ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT Primer to Understanding the Centuries-Old Struggle

ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT Primer to understanding the centuries-old struggle “When people criticize Zionists, they mean Jews. You’re talking anti-Semitism.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. HonestReporting Defending Israel From Media Bias ANTI-SEMITISM IS THE DISSEMINATION OF FALSEHOODS ABOUT JEWS AND ISRAEL www.honestreporting.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1 History Part 2 Jerusalem Part 3 Delegitimization Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Part 4 Hamas, Gaza, and the Gaza War Part 5 Why Media Matters 2 www.honestreporting.com ISRAELI-ARAB CONFLICT Primer to understanding the centuries-old struggle The Middle East nation we now know as the State of Israel has existed throughout history under a va riety of names: Palestine, Judah, Israel, and others. Today it is surrounded by Arab states that have purged most Jews from their borders. Israel is governed differently. It follows modern principles of a western liberal democracy and it pro vides freedom of religion. Until the recent discovery of large offshore natural gas deposits, Israel had few natural resources (including oil), but it has an entrepreneurial spirit that has helped it become a center of research and development in areas such as agriculture, computer science and medical tech nologies. All Israeli citizens have benefited from the country’s success. Yet anti-Israel attitudes have become popular in some circles. The reason ing is often related to the false belief that Israel “stole” Palestinian Arab lands and mistreated the Arab refugees. But the lands mandated by the United Nations as the State of Israel had actually been inhabited by Jews for thousands of years. -

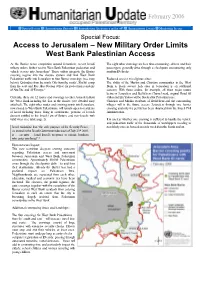

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

Strateg Ic a Ssessmen T

Strategic Assessment Assessment Strategic Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Volume 19 Volume The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | No. 4 No. Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | January 2017 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities Emily B. Landau and Ephraim Asculai Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Abstracts | 3 The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century | 9 Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | 29 Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | 43 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? | 57 Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army | 67 Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation | 79 Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects | 93 Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations | 103 Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities | 117 Emily B. -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

“Is the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process Dead?” April 19, 2019 PART

The Brookings Institution Brookings Cafeteria Podcast “Is the Israeli-Palestinian peace process dead?” April 19, 2019 PARTICIPANTS: FRED DEWS Host KHALED ELGINDY Nonresident Fellow - Foreign Policy, Center for Middle East Policy TAMARA COFMAN WITTES Senior Fellow - Foreign Policy, Center for Middle East Policy DAVID WESSEL Senior Fellow, Economic Studies Director, The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy 1 (MUSIC) DEWS: Welcome to the Brookings Cafeteria, the podcast about ideas and the experts who have them. I'm Fred Dews. On today's episode, an interview with Khaled Elgindy, author of a new book from the Brookings Institution Press, Blind Spot: America and the Palestinians, from Balfour to Trump. Elgindy is a nonresident fellow in the Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings and previously served as an advisor to the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah on permanent status negotiations with Israel from 2004 to 2009 and was a key participant in the Annapolis negotiations throughout 2008. Conducting the interview is Tamara Cofman Wittes. Senior fellow in the Center for Middle East Policy, she served as deputy assistant secretary of state for near eastern affairs from 2009 into 2012. Also, on today's show, Wessel's Economic Update. Today, Senior Fellow David Wessel, offers three reasons why we don't necessarily have to address the rising U.S. budget deficit through increased taxes and cutting spending right now. You can follow the Brookings podcast network on Twitter @policypodcasts to get information about and links to all of our shows, including our new podcast, The Current, which is replacing our 5 on 45 podcast. -

Civil Resilience Network Conceptual Framework for Israel's Local & National Resilience

Israel Trauma Coalition for Response and Preparedness Civil Resilience Network Conceptual Framework for Israel's Local & National Resilience Version B Elul 5769 August 2009 Civil Resilience Network – Version B - 2 - Elul 5769 August 2009 "It's not the strongest of the species that survives nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change" (Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, 1859) … "The entire people is the army, the entire land is the front" (David Ben-Gurion, May 1948) … "Israel has nuclear weapons and the strongest air force in the region, but the truth is that it is weaker than a spider's web" (Hassan Nasrallah, May 26, 2000) ... "The durability of spider webs enable them to absorb the concentrated pressure of a weight ten times that of the most durable artificial fiber" (P. Hillyard, The Book of the Spider, 1994) Civil Resilience Network – Version B - 3 - Elul 5769 August 2009 Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................ 3 Funders: UJA Federation of New York ....................................................................... 5 Partners ........................................................................................................................... 5 THE ISRAEL TRAUMA COALITION: RESPONSE AND PREPAREDNESS............................... 5 THE REUT INSTITUTE ..................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements........................................................................................................ -

Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian

Selected articles concerning Israel, published weekly by Suburban Orthodox Toras Chaim’s (Baltimore) Israel Action Committee Edited by Jerry Appelbaum ( [email protected] ) | Founding editor: Sheldon J. Berman Z”L Issue 8 8 7 Volume 2 1 , Number 1 9 Parshias Bamidbar | 48th Day Omer May 1 5 , 2021 Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian Frustration By Dov Lieber and Felicia Schwartz wsj.com May 12, 2021 It is not that the police caused the uptick in violence, forces by Monday evening from Shei kh Jarrah. The but they certainly ran headfirst, full - speed, guns forces were there as part of security measures surrounding blazing into the trap that was set for them. the nightly protests. When the secretive military chief of the Palestinian As the deadline passed, the group sent the barrage of Islamist movement Hamas emerged from the shadows last rockets toward Jerusalem, precipitating the Israeli week, he chose to weigh in on a land dispute in East response. Jerusalem, threatening to retaliate against Israel if Israeli strikes and Hamas rocket fire have k illed 56 Palestinian residents there were evicted from their homes. Palestinians, including 14 children, and seven Israelis, “If the aggression against our people…doesn’ t stop including one child, according to Palestinian and Israeli immediately,” warned the commander, Mohammad Deif, officials. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel “the enemy will pay an expensive price.” has killed dozens of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad Hamas followed through on the threat, firing from the operatives. Gaza Strip, which it governs, over a thousand rockets at Althou gh the Palestinian youth have lacked a single Israel since Monday evening.