International Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woodturning Magazine Index 1

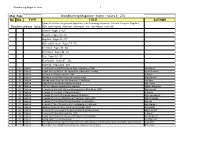

Woodturning Magazine Index 1 Mag Page Woodturning Magazine - Index - Issues 1 - 271 No. No. TYPE TITLE AUTHOR Types of articles are grouped together in the following sequence: Feature, Projects, Regulars, Readers please note: Skills and Projects, Technical, Technique, Test, Test Report, Tool Talk Feature - Pages 1 - 32 Projects - Pages 32 - 56 Regulars - Pages 56 - 57 Skills and Projects - Pages 57 - 70 Technical - Pages 70 - 84 Technique - Pages 84 - 91 Test - Pages 91 - 97 Test Report - Pages 97 - 101 Tool Talk - Pages 101 - 103 1 36 Feature A review of the AWGB's Hay on Wye exhibition in 1990 Bert Marsh 1 38 Feature A light hearted look at the equipment required for turning Frank Sharman 1 28 Feature A review of Raffan's work in 1990 In house 1 30 Feature Making a reasonable living from woodturning Reg Sherwin 1 19 Feature Making bowls from Norfolk Pine with a fine lustre Ron Kent 1 4 Feature Large laminated turned and carved work Ted Hunter 2 59 Feature The first Swedish woodturning seminar Anders Mattsson 2 49 Feature A report on the AAW 4th annual symposium, Gatlinburg, 1990 Dick Gerard 2 40 Feature A review of the work of Stephen Hogbin In house 2 52 Feature A review of the Craft Supplies seminar at Buxton John Haywood 2 2 31 Feature A review of the Irish Woodturners' Seminar, Sligo, 1990 Merryll Saylan 2 24 Feature A review of the Rufford Centre woodturning exhibition Ray Key 2 19 Feature A report of the 1990 instructors' conference in Caithness Reg Sherwin 2 60 Feature Melbourne Wood Show, Melbourne October 1990 Tom Darby 3 58 -

OCCASION This Publication Has Been Made Available to the Public on The

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] 4 1 . 0 1.25 1 6 I C 3 V D i s t r . -

The Ornamental Lathe

The Ornamental Lathe G. Phil Poirier Bonny Doon Engineering Taos, New Mexico, USA Introduction Originating from the simple or common lathe, which is known as the mother of all machine tools, the ornamental lathe is arguably the most capable machine tool in the history of mechanization. In the 1981 Metalsmith Journal, Kener Bond Jr., professor of art at the Rochester Institute of Technology, wrote, “Contemporary jewelers have been less aware of the rose engine and ornamental lathes and the historical contributions they have made to jewelry design and production.”1 This paper was inspired by Bond's quote and will briefly cover the history of the ornamental lathe and how it works, give an overview of many of its accessories, and share how it can be utilized in the design and creation of new ideas in the jewelry industry. Evolution of the Lathe into the Ornamental Lathe The plain or simple lathe dates back over 3000 years. Not until the 15th century did the simple lathe start evolving into something more complex. One of the first of many evolutions included the invention of a traversing spindle, a spindle which could move in and out of its bearings along the lathe’s long axis. This would then impart a screw thread into the workpiece which was attached to one end of the spindle and would traverse the lathe bed with the spindle.2 This meant that the simple lathe could now create the threads needed to make screws. The earliest published illustrations of an ornamental lathe is in Besson’s Theatrum instrumentorum et machinarum.3 The illustration in Figure 1 shows several of the ornamental additions to the simple lathe. -

2012 San José

2012 San José 2012 symposium planning guide Name Contact Info in case of loss PRESIDENT'S WELCOME San José • June 8-10, 2012 Dear Woodturning Friends, On behalf of the American Association of Woodturners Board of Directors, welcome to the 26th AAW international symposium. Our annual meeting constitutes the largest woodturning expo under one roof anywhere in the world. This symposium is the culmination of another year of advancement for the AAW – one that finds the organization at 14,000 members strong and poised for significant growth ahead. The artistic and technological advances that have reshaped woodturning since AAW’s founding in 1986 will be on full display here in San José. The AAW has truly become a global institution, with more than 1,030 international members, many of whom will be with us in San José this week, coming from dozens of countries. We deeply value the perspectives that our international members provide and look forward to expanding their ranks in years ahead. For 26 years, the AAW has been the premier advocate for the ancient craft and art of woodturning, an activity that has seen phenomenal growth during the last quarter century by both part-time hobbyists and studio professionals. While the association publishes a world-class journal, maintains a topical website, and supports hundreds of local chapters with a variety of services, it is at this symposium that members see the creative and inspiring demonstrations and can experience hands- on interactions with the world’s best woodturners. We are delighted to bring the AAW annual symposium to the heart of Silicon Valley this year. -

OT Lathes Need a Means to Control Angle Via the Sliderest

ORNAMENTAL OBSESSIONS Jon Magill will be a demonstrator at the 2016 AAW international symposium in Atlanta, Georgia, June 9-12, 2016. For WHAT IS OLD IS more, visit woodturner.org. NEW AGAIN A History of Contemporary Ornamental Turning Jon Magill here seem to be two types of of the lathes used, how the workpiece people, those who look at some- is manipulated, and the cutters that T thing and say, “That’s pretty,” are employed. Those constitute the and those who ask, “How did they root of OT and the nearly infinite pat- do that?” Most woodturners, myself terns that are possible, once mastered. included, seem to fall into the latter category. That explains in a nutshell What is OT? how I became fascinated with the rela- OT is all about geometry, the enablers tively obscure realm of ornamental of that geometry being the specialized turning, or OT for short. lathes, the ingenious chucks, and the OT is a specialized subcategory of multitude of various cutters. Starting woodturning, much the way seg- with the lathes, we encounter the first mented turning can be thought of. major division of the OT realm into its Generally speaking, OT is a collection two main subcategories: index work of techniques used to add decoration, and engine turning. or “ornamentation,” to turned objects. As its name implies, index work is In some senses, it might be considered carried out when the spindle on the geometric carving that is typically lathe is indexed to a new fixed posi- accomplished with a rotating cutter of tion, using an indexing wheel and a some sort. -

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume Adkins, Jim DAW1019 Native American Baskets Part 1 2014 20 DAW1021 Native American Baskets Part 2 2014 21 Arledge, Jimmie DAW0490 Surface Embellishment 2004 10 Avisera, Eli DAW0789 Bowl with Leaves Inlay 2010 1 DAW0791 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring 2010 2 DAW0793 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring in Off-Center 2010 3 DAW0795 Goblet w/Star Segment & Trembleur 2010 4 DAW0797 Square Bowl w/ Off-Center 2010 5 Baldwin, Doug DAW2358 Photography for Wood Turners 2015 1 DAW2360 Photoshop for Wood Turners 2015 2 DAW2660 Light & Shadow - Photographing Wood Objects 2017 1 Barnes, Gary DAW2420 Three-Piece Stacking Salt/Spice Box 2016 1 Bassett, Kevin DAW0665 Turning a Double Natural Edge Bowl 2008 1 DAW2422 An Acorn Ring Box w/ Secret Compartment 2016 2 Batty, Stuart DAW0733 Bowl Turning Techniques using a Gouge 2009 3 DAW0735 The Six Fundamental Wooduring Cuts 2009 4 DAW0755 Dueling Lathes: two different ways to turn a bowl 2009 14 DAW2424 Stuart Batty & Mike Mahoney Dual 2016 3 DAW2426 Bowl Turning w/ the 40/40 Grind 2016 4 DAW2428 Perfecting the Art of Cutting 2016 5 DAW2430 Seven Set-up Fundamentals 2016 6 DAW2692 Stuart Batty and Mike Mahoney Dual 2017 17 Beaver, John DAW2432 Bangles 2016 7 DAW2434 Flying Rib Vase 2016 8 1 SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume DAW2436 Wave Bowls 2016 9 Berry, Bill DAW0737 Turning Tree Crotches 2009 5 DAW2352 Air Brushing on Turnings 2014 26 Bosch, Trent DAW0462 Carving 2003 1 DAW0464 Basic Bowl -

February 2008

MMINNESOTAINNESOTA WWOODTURNERSOODTURNERS ASSOCIATION in association with the American Association of Woodturners February 2008 Inside This Issue: 2 President’s Corner 8 Tim Heil Handles 4 Basic Black Preview 12 Al Stirt 5 Sawdust to Ribbons 14 Club Calendar 6 Member profiles 13 Annual Holiday Party 8 Hands-on session with Dave Hout 14 Calendar of events Minnesota Woodturners President’s Corner cide what type of carving/ Association embellishment to use on a particular piece? What Board Members shape will present the best President look? Does the shape Jim Zangl come first and the embel- [email protected] lishment follow or is a pat- 651-645-4696 tern decided on and a shape made for the pat- Program Director Dan Rominski tern? Is it all envisioned [email protected] from the outset or does it 651-436-5928 evolve on the lathe as the wood is exposed? Go to Secretary his website and look at his Mike Hunter [email protected] work. Then come to the 612-922-1197 Jim Zangl demo and meet and watch the man express how the Treasurer/Membership creation happens. Pam Johnson [email protected] I would like to welcome 651-430-1738 Scott Thornhill, Carole Any suggestions to im- Magnuson, Larry McPeck prove the club will be Newsletter Editor and Lisa Botton to the greatly appreciated. Please Jeff Luedloff Board. To the departing feel free to discuss them [email protected] with myself or any board 952-496-1177 board members Bob, Bruce and Joe , thanks for the member. Librarian past years of hard work for Lisa Botten the club and I am sure I Be an active part of the speak for all the members club-not just a bystander. -

2020-12 December Newsletter

Gulf Coast Woodturner December 2020 Newsletter President’s Corner 2021 dues are due. Please renew your membership if you haven't already. You can go to our website and use a credit card, preferably yours, or send a check in care of Walter Mooney. The Ornament Exchange will be different this year. The deadline for photo entries is December 14th. Camp Hope is a residence program for combat veterans with PTSD. GCWA has donated pens made by members, later did a demonstration, and most recently conducted a pen class with four lathes at their facility. We will conduct another pen turning class there the afternoon of January 16th and could use additional volunteers. Please contact me or Walter Mooney about helping our vets. Gold Gallery: Photos of your projects should be sent to Scott Haddix for inclusion in your section of the Gold Gallery on our website. Formerly, Show and Tell ribbon winners were automatically added to the gallery. Now we ask that you take a photo of each project and submit it. Speaking of photos, in the Members Only section of our website there is a Gallery of Rogues ie. GCWA members. This is where you can browse the photos to refresh your memory, especially since it's been so long since we have met in person. It may also be used to find the name associated with a face you recognize. About half of the members have photos posted. If you are absent from the gallery please take a selfie and email it to our webmaster, Scott Haddix. -

Sawg News 0805

20th Anniversary TurningTalk Year Turning Tomorrow’s Treasures Issue No 165 Newsletter of the South Auckland Woodturners Guild May 2008 In this issue: This month we celebrate our Memories 2 Club Honours Boards 3 Coming Events 4 Editorial 4 Club Activities 5,6 Terry’s Hot Tips 7 Creativity reigns 8 On Wednesday 14th May we are holding a combination of our Annual General Out & about 9 Meeting and a celebration of our Guild’s 20th Anniversary . and it’s a time News Editors’ workshop 9 well worth celebrating! Over those 20 years the club has grown from that first meeting of a handful of enthusiastic woodturners meeting in a high-school wood-work room to a thriving, dynamic community of over 140 members, SAWG COMMITTEE young and old, men and women, who get together at least once a week in a President large, well-equipped clubroom that is the envy of many clubs around the world. Michael Bernard 09 425 6782 Inside are anecdotes from some of those early members, an Honours Board of Vice President special contributors as well as the usual reminders of the past, present and Dick Veitch 298 5775 Past President future activities that mould this club. Farouk Khan 580 2366 In these days of so many uncertainties, we do well to recognise and pay tribute Secretary to those who have freely given their time and talents to bring us so far to where Tom Pearson 575 4994 we are today. Treasurer You are very welcome to join in our celebrations, wherever you are! Cathy Langley 630 2091 Editor Mike Clausen 525 3586 Winning Smiles from a pair of Winners Members: Mac Duane, Terry Meekan, When the end of Term One Awards were announced Dave Small (left) and Gordon Pembridge, Bruce Wood had something to smile about. -

High Desert Turning: Vol 21, Issue 10 October 3, 2020

New Mexico Woodturners – High Desert Turning: Vol 21, Issue 10 October 3, 2020 High Desert Turning www.nmwoodturners.org One Year Membership: $25 individual, $30 family Contact Mark Smith, 505-270-6316 or [email protected] The President’s Turn Fall is here and the leaves are 'turning'... First and foremost, I want to thank our Program and Virtual Committees as they continue to work their magic delivering demos and educational content! Hopefully we'll be able to gather in person soon, but they've done a marvelous job in the meantime. As for our October virtual demo, Eddie Bell will be demonstrating and discussing the fascinating world of ornamental turning on October 3rd… see the Programs section on the website as well as the Newsletter for more on this. Watch your email the week prior for the Zoom details to join! Also, check out the recent threads on ornamental turning on the AAW website! We will have another on-line social the middle of October – invites to go out the first week of October. And don't forget, we always welcome NEW MEMBERS to join New Mexico Woodturners. All that's needed is an interest in woodturning. Stay well, stay safe, and don't miss Eddie's demo! Rick Judd Elected Officers, Directors & Committee Chairs President: Rick Judd 612-280-8300 Newsletter: Scott Kershaw 406-274-2931 Vice President: Jake Jacobson 505-417-2361 Photographer: Woody Stone 828-808-7876 Treasurer: Mark Smith 505-270-6316 Raffle Coordinator: Dean Cross 575-644-8945 Secretary: Sally Breeden 505-352-0159 Librarian: Michael Andersen 575-209-0172 State -

MDF Rose Engine Construction Instructions Jon Magill V6 – 2/27/07

MDF Rose Engine Construction Instructions Jon Magill v6 – 2/27/07 This article is aimed at those people who have been initially intrigued with ornamental turning and want to give it a try but found the barriers to getting started too intimidating. If you have watched a demo at a past symposium, or perhaps read an old article with interest, but quickly lost enthusiasm after digging a little deeper and realizing how difficult or expensive it is to find, purchase and restore an antique ornamental lathe, then this may be the project for you. This article presents a very simple design for a rose engine lathe which is capable of doing high quality work, yet is easy to build in a home workshop. The Design There have been countless designs for rose engine lathes and there are many ways to make a rose en- gine. Likewise, there are an almost infinite number of possibilities for features that can be included when designing or building a rose engine. For the purpose of this article, the focus is on a simple design, a be- ginner’s lathe to gain experience on. That is not to say that this lathe is limited in capabilities. This design is simple yet very capable. It has also been designed to allow adding optional features to it. A future arti- cle will describe some advanced features to add on to the lathe and ideas for where to go once you have gained some experience using your first rose engine. Paul Fletcher, an accomplished and ingenious orna- mental turner from England, shared his basic design for an MDF rose engine lathe. -

Website News >>> Jim Mccleary Greetings and Welcome to Our Brand New, the AWA Website Hasawa a New Look

in this issue >>> July • President’s message 2018 • Changes on website • Meet a member • Shop tips • Club Projects AWA News President’s message… Website news >>> Jim McCleary Greetings and Welcome to our brand new, The AWA website hasAWA a new look. first edition, combo newsletter and presidential I was so impressed with Marvin’s work on message. I think that Pat, our webmaster, has the AWA website (previous webmaster). done an awesome job in the production of this newsletter. Please take the time to read it all, What a neat/organized coded site to take because it is packed with a lot of good info. over! But just like life – when you take Also please help her, with any input or articles over something you want to make it your you would like to see in the newsletter. GREAT own. So bear with me as I make some JOB PAT. Jim at Pinal County Fair changes. I am looking forward to watching John Lea's, Fair Rose engine demo at the July meeting. This will be the first time seeing this piece of machinery I hope everyone has an I do need your input, tips, links, reviews! awesome Fourth of July - any Have you bought a new book or video - and used in a demo. All I know it is one big piece of machinery. They're bringing it on a large fireworks, boating, barbecue, can you let us know what you think of it? golfing, or swimming? As long as truck, with a liftgate to unload it at the Pyle Have you been to a class? What was center for the meeting.