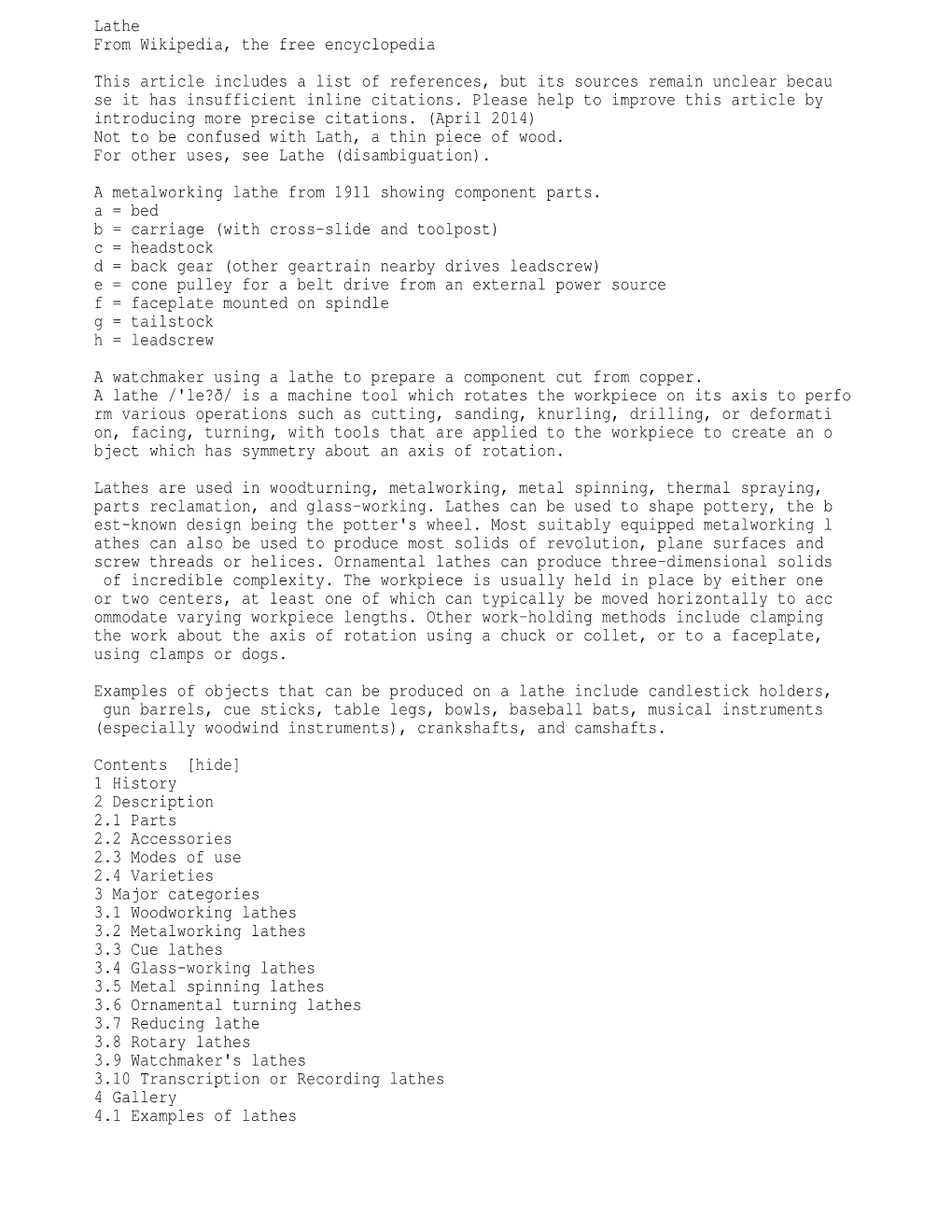

Lathe from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia This Article Includes a List of References, but Its Sources Remain Unclear Becau Se It Has Insufficient Inline Citations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woodturning Magazine Index 1

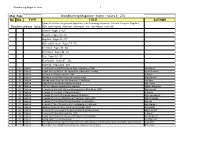

Woodturning Magazine Index 1 Mag Page Woodturning Magazine - Index - Issues 1 - 271 No. No. TYPE TITLE AUTHOR Types of articles are grouped together in the following sequence: Feature, Projects, Regulars, Readers please note: Skills and Projects, Technical, Technique, Test, Test Report, Tool Talk Feature - Pages 1 - 32 Projects - Pages 32 - 56 Regulars - Pages 56 - 57 Skills and Projects - Pages 57 - 70 Technical - Pages 70 - 84 Technique - Pages 84 - 91 Test - Pages 91 - 97 Test Report - Pages 97 - 101 Tool Talk - Pages 101 - 103 1 36 Feature A review of the AWGB's Hay on Wye exhibition in 1990 Bert Marsh 1 38 Feature A light hearted look at the equipment required for turning Frank Sharman 1 28 Feature A review of Raffan's work in 1990 In house 1 30 Feature Making a reasonable living from woodturning Reg Sherwin 1 19 Feature Making bowls from Norfolk Pine with a fine lustre Ron Kent 1 4 Feature Large laminated turned and carved work Ted Hunter 2 59 Feature The first Swedish woodturning seminar Anders Mattsson 2 49 Feature A report on the AAW 4th annual symposium, Gatlinburg, 1990 Dick Gerard 2 40 Feature A review of the work of Stephen Hogbin In house 2 52 Feature A review of the Craft Supplies seminar at Buxton John Haywood 2 2 31 Feature A review of the Irish Woodturners' Seminar, Sligo, 1990 Merryll Saylan 2 24 Feature A review of the Rufford Centre woodturning exhibition Ray Key 2 19 Feature A report of the 1990 instructors' conference in Caithness Reg Sherwin 2 60 Feature Melbourne Wood Show, Melbourne October 1990 Tom Darby 3 58 -

Bodging Scotland CWA-1

CWA SKILLS DEVELOPMENT SCHEME Green woodworking and pole lathe turning for beginners Hosted by: Dunnottar Bodgers Group & Dunnottar Woodland Park Association Stonehaven Saturday 3rd and Sunday 4th April 2010 INVITATION Dunnottar Bodgers Group and the Dunnottar Woodland Park Association, in conjunction with the Community Woodlands Association, are pleased to extend a warm invitation to you to join them at the Green woodworking and pole lathe turning for beginners course held near the quarry area of Dunnottar woods, Stonehaven, Aberdeenshire. This event will offer another great opportunity to network, highlight and discuss common issues and concerns, share your skills and experiences, and learn from the inspirational work of others. This learning and networking opportunity is aimed at members of community woodland groups and members of the general public that would wish to learn more about the traditional craft of bodging and green wood turning. The objectives of the course are: • To provide an opportunity for participants to take part in a variety of green wood working processes. • Use bodging processes to make a simple wooden stool from locally sourced timber and/or contribute to the manufacture of shaving horses for use by the host group. The course will consist of an informal meeting and meal in a local hotel on the Friday evening prior event where participants can meet and have a general discussion. Kenny Grieve is the trainer for this course and will be on hand to answer any questions before starting the course proper the following day. On the Saturday morning the participants will embark on the two day practical course based in Dunnottar woods, where the Dunnottar Bodgers Group have established a base. -

The Wood Turning Center Is a Non-Profit Arts Institution Dedicated

Chronological List of Exhibitions & Publications The Center for Art in Wood 141 N. 3rd Street | Philadelphia, PA 19106 | 215-923-8000 Exhibitions in italics were accompanied by publications. Title of exhibition catalogue is listed with its details. 2013 Shadow of the Turning: The Art of Binh Pho, The Center for Art in Wood, October 25, 2013 – January 18, 2014. Organized by Binh Pho & Kevin Wallace Shadow of the Turning is a traveling exhibition focuses on art, philosophy and storytelling of artist Binh Pho. Blending the mythic worlds of fairy tale, fantasy, adventure and science fiction, this exhibit creates a bridge between literature, art world approaches to concept and narrative, craft traditions and mixed media approaches. The story is “illustrated” using an exciting new body of work by Binh Pho, which combines woodturning, sculpture, painting and art glass. Exhibited Artist: Binh Pho 2013 Hogbin on Woodturning: Pattern from Process, The Center for Art in Wood Museum Store, September 19 – October 21, 2013 The exhibition Pattern from Process presents objects created for the instructional publication titled Hogbin on Woodturning. The 14 objects by Stephen Hogbin in the publication are represented in the exhibition with related material. Reading about the projects included in the publication and seeing the object will help students, educators, and woodworkers develop a clearer understanding of the construction and final quality of their work. Exhibited Artist: Stephen Hogbin 2013 allTURNatives: Form + Spirit 2013, The Center for Art in Wood, August 2 – October 12, 2013 Celebrating the 18th year of the International Turning Exchange Residency (ITE) program, the Center is proud to host the international artists, photojournalist and scholar who worked together for 2 months at the UArts in Philadelphia and explored new directions in their work. -

OCCASION This Publication Has Been Made Available to the Public on The

OCCASION This publication has been made available to the public on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. DISCLAIMER This document has been produced without formal United Nations editing. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or its economic system or degree of development. Designations such as “developed”, “industrialized” and “developing” are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. Mention of firm names or commercial products does not constitute an endorsement by UNIDO. FAIR USE POLICY Any part of this publication may be quoted and referenced for educational and research purposes without additional permission from UNIDO. However, those who make use of quoting and referencing this publication are requested to follow the Fair Use Policy of giving due credit to UNIDO. CONTACT Please contact [email protected] for further information concerning UNIDO publications. For more information about UNIDO, please visit us at www.unido.org UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26026-0 · www.unido.org · [email protected] 4 1 . 0 1.25 1 6 I C 3 V D i s t r . -

The Ornamental Lathe

The Ornamental Lathe G. Phil Poirier Bonny Doon Engineering Taos, New Mexico, USA Introduction Originating from the simple or common lathe, which is known as the mother of all machine tools, the ornamental lathe is arguably the most capable machine tool in the history of mechanization. In the 1981 Metalsmith Journal, Kener Bond Jr., professor of art at the Rochester Institute of Technology, wrote, “Contemporary jewelers have been less aware of the rose engine and ornamental lathes and the historical contributions they have made to jewelry design and production.”1 This paper was inspired by Bond's quote and will briefly cover the history of the ornamental lathe and how it works, give an overview of many of its accessories, and share how it can be utilized in the design and creation of new ideas in the jewelry industry. Evolution of the Lathe into the Ornamental Lathe The plain or simple lathe dates back over 3000 years. Not until the 15th century did the simple lathe start evolving into something more complex. One of the first of many evolutions included the invention of a traversing spindle, a spindle which could move in and out of its bearings along the lathe’s long axis. This would then impart a screw thread into the workpiece which was attached to one end of the spindle and would traverse the lathe bed with the spindle.2 This meant that the simple lathe could now create the threads needed to make screws. The earliest published illustrations of an ornamental lathe is in Besson’s Theatrum instrumentorum et machinarum.3 The illustration in Figure 1 shows several of the ornamental additions to the simple lathe. -

2012 San José

2012 San José 2012 symposium planning guide Name Contact Info in case of loss PRESIDENT'S WELCOME San José • June 8-10, 2012 Dear Woodturning Friends, On behalf of the American Association of Woodturners Board of Directors, welcome to the 26th AAW international symposium. Our annual meeting constitutes the largest woodturning expo under one roof anywhere in the world. This symposium is the culmination of another year of advancement for the AAW – one that finds the organization at 14,000 members strong and poised for significant growth ahead. The artistic and technological advances that have reshaped woodturning since AAW’s founding in 1986 will be on full display here in San José. The AAW has truly become a global institution, with more than 1,030 international members, many of whom will be with us in San José this week, coming from dozens of countries. We deeply value the perspectives that our international members provide and look forward to expanding their ranks in years ahead. For 26 years, the AAW has been the premier advocate for the ancient craft and art of woodturning, an activity that has seen phenomenal growth during the last quarter century by both part-time hobbyists and studio professionals. While the association publishes a world-class journal, maintains a topical website, and supports hundreds of local chapters with a variety of services, it is at this symposium that members see the creative and inspiring demonstrations and can experience hands- on interactions with the world’s best woodturners. We are delighted to bring the AAW annual symposium to the heart of Silicon Valley this year. -

The Turner Issue 39 May 2014 Full

TH ETURNER THE WORSHIPFUL COMPANY OF TURNERS OF LONDON June 2014 On 29 th May 2014, Ascension Day, I became the 344 th Master of the Worshipful Company of Turners. Only 344 Masters in the 410 years since our Royal Charter in 1604 because for most of our first 160 years it was usual for Masters to serve for two-year terms. For many years before 1604 we believe that two Wardens governed the Guild of Turners and in the earliest times we know that in 1179 “the gild of strangers of which Warner le Turner is elderman” owed 40 shillings for not being properly licensed by the King. What an honour and a privilege to continue in a succession spanning at least 835 years. I am hugely indebted to the long line of distinguished Masters who have preceded me leaving the Company in such good health, and to our capable Clerk, Wardens, Master’s Steward, Committee Chairmen and Members, Beadle, Almoner, Archivist and Chaplain with whom to share the responsibilities of office. And I owe special thanks to Rhidian Jones who has proved to be yet another outstanding Master of the Company and whose wise counsel will be available to me as Deputy Master. My first experience of turning came in the 1960s when, as a young engineer in a modern aluminium rolling mill, I learned about lathe production of the micron finishes and cambers of mill rolls that are needed to produce sheet to the necessary gauge, flatness, surface finish and temper. One of my very first assignments involved production of high-strength, heat-treated aircraft sheet for the supersonic Concorde. -

OT Lathes Need a Means to Control Angle Via the Sliderest

ORNAMENTAL OBSESSIONS Jon Magill will be a demonstrator at the 2016 AAW international symposium in Atlanta, Georgia, June 9-12, 2016. For WHAT IS OLD IS more, visit woodturner.org. NEW AGAIN A History of Contemporary Ornamental Turning Jon Magill here seem to be two types of of the lathes used, how the workpiece people, those who look at some- is manipulated, and the cutters that T thing and say, “That’s pretty,” are employed. Those constitute the and those who ask, “How did they root of OT and the nearly infinite pat- do that?” Most woodturners, myself terns that are possible, once mastered. included, seem to fall into the latter category. That explains in a nutshell What is OT? how I became fascinated with the rela- OT is all about geometry, the enablers tively obscure realm of ornamental of that geometry being the specialized turning, or OT for short. lathes, the ingenious chucks, and the OT is a specialized subcategory of multitude of various cutters. Starting woodturning, much the way seg- with the lathes, we encounter the first mented turning can be thought of. major division of the OT realm into its Generally speaking, OT is a collection two main subcategories: index work of techniques used to add decoration, and engine turning. or “ornamentation,” to turned objects. As its name implies, index work is In some senses, it might be considered carried out when the spindle on the geometric carving that is typically lathe is indexed to a new fixed posi- accomplished with a rotating cutter of tion, using an indexing wheel and a some sort. -

The Sawdust Sentinel

The Sawdust Sentinel Monthly newsletter of Woodworkers Club of Houston Volume 38 Issue 3 March 2021 Inside this Issue MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT WWCH Calendar ............................... p. 1 St. Patrick’s Day themed woodworking may be a little some- President’s Message .......................... p. 1 thing to try out this month. After all, we could all use the Luck of Splinter group Info .............................. p. 2 the Irish, right? Toy of the Month ................................ p. 2 Newsletter Name ................................ p. 2 And with Spring soon to arrive, and with this an expectation Show and Tell ................................. p. 2-4 among many with non-climate controlled shops, an anticipation Vendor Ad .......................................... p. 5 of comfortably long days making sawdust. But whether your shop is climate controlled or not, these months of beautiful weather, and days getting longer, encourage us to continue to WWCH Calendar do our best at woodworking. Monthly Meeting (via Zoom) .......... 13 Mar Have fun making sawdust! Cheers! Furniture Meeting (via Zoom)......... 04 Mar Scroll saw Meeting (via Zoom) ....... 10 Mar Hand tool Meeting (via Zoom)........ 28 Mar Chris Schwartz WWCH President 2021 Dues Waived Due to the COVID crisis’s impact to club March Splinter Group activities and the lack thereof, the WWCH Board has decided that all members in The Scroll Saw Splinter Group will have a monthly Zoom meet- good standing for 2020 will have their ing Norm Nichols will send out invite a week before the meeting dues waived for 2021. That’s right, if you date. If you wish to join the scroll saw splinter group please con- were a paid member for 2020 you will tact Norm Nichols ([email protected]) continue to be a member through this The Furniture and Finishing Splinter will meet Thursday, March year at no additional cost. -

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume Adkins, Jim DAW1019 Native American Baskets Part 1 2014 20 DAW1021 Native American Baskets Part 2 2014 21 Arledge, Jimmie DAW0490 Surface Embellishment 2004 10 Avisera, Eli DAW0789 Bowl with Leaves Inlay 2010 1 DAW0791 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring 2010 2 DAW0793 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring in Off-Center 2010 3 DAW0795 Goblet w/Star Segment & Trembleur 2010 4 DAW0797 Square Bowl w/ Off-Center 2010 5 Baldwin, Doug DAW2358 Photography for Wood Turners 2015 1 DAW2360 Photoshop for Wood Turners 2015 2 DAW2660 Light & Shadow - Photographing Wood Objects 2017 1 Barnes, Gary DAW2420 Three-Piece Stacking Salt/Spice Box 2016 1 Bassett, Kevin DAW0665 Turning a Double Natural Edge Bowl 2008 1 DAW2422 An Acorn Ring Box w/ Secret Compartment 2016 2 Batty, Stuart DAW0733 Bowl Turning Techniques using a Gouge 2009 3 DAW0735 The Six Fundamental Wooduring Cuts 2009 4 DAW0755 Dueling Lathes: two different ways to turn a bowl 2009 14 DAW2424 Stuart Batty & Mike Mahoney Dual 2016 3 DAW2426 Bowl Turning w/ the 40/40 Grind 2016 4 DAW2428 Perfecting the Art of Cutting 2016 5 DAW2430 Seven Set-up Fundamentals 2016 6 DAW2692 Stuart Batty and Mike Mahoney Dual 2017 17 Beaver, John DAW2432 Bangles 2016 7 DAW2434 Flying Rib Vase 2016 8 1 SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume DAW2436 Wave Bowls 2016 9 Berry, Bill DAW0737 Turning Tree Crotches 2009 5 DAW2352 Air Brushing on Turnings 2014 26 Bosch, Trent DAW0462 Carving 2003 1 DAW0464 Basic Bowl -

Green Woodworking Spring Greens Dorset Make Beautiful Objects from Freshly Felled Wood

11 | EXPERIENCE | GREAT DAYS OUT Visit www.bbccountryfilemagazine.com/daysout LearN greeN WoodWorKING Spring greens Dorset Make beautiful objects from freshly felled wood, using time-honoured methods and tools As featured on ABOVE Creating a spurtle is hard, but Words: Tor McIntosh Pictures: Jeff Gilbert Mastercrafts, satisfying, work BELOW LEFT Guy the see page 55 woodworker BELOW RIGHT Tools of the trade Guy polishes a partly USEFUL INFO finished ‘spurtle’ with © 2010 Google - Map data © 2010 Tele Atlas wood shavings Course reen woodworkers aim to expend as little energy felled timber – green wood still contains sap, meaning HIghER HOLDItch FARM Gas possible,” explains Guy Mallinson, my tutor, it’s soft and easy to work with. However, since green Holditch TA20 4NL as I pound the wooden club onto the froe tool for the wood is cut along the grain, it remains strong and can 01460 221102 umpteenth time, attempting to cleave a sycamore log be used to produce long-lasting objects. www.mallinson.co.uk into quarters. “With no machinery to do the hard work The two-day Pole Lathe and Green for you, it’s vital to pace yourself during the tree-to- FINDING THE RHytHM Woodworking course costs £287.50 product process,” he continues. Finally the stubborn The next stage in the spurtle-making process and includes lunch, tea and snacks. chunk of wood divides. Wiping the sweat from my is shaping the billet using a pole lathe, a simple brow, it’s clear that I have a lot to learn about the age- woodturning apparatus dating back to the Viking era. -

Greenwood Working Weekend Dunnet Forestry Trust 14Th & 15Th

Greenwood Working Weekend Dunnet Forestry Trust 14th & 15th July 2012 This event is part of the CWA Knowledge and Skill Development Training Programme, funded by the Scottish Government Skills Development Scheme and the Robertson Trust. Greenwood Working Weekend Dunnet Forestry Trust 14th & 15th July 2012 This report summarises and gives feedback from the two day Greenwood Working event delivered as part of the CWA Knowledge and Skills Development Scheme 2011/12. This event took place on Saturday and Sunday 14th & 15th July 2012, with a total of 17 delegates learning new skills and gaining more experience with greenwood work. Why did we do this? Set up a green wood working group – a new skill in the locality Broaden the skill base of our current volunteers and attract new ones Create equipment which can be used by forest ranger to diversify activities offered to community groups Find a means of making replacement xylophone beaters on site! Weekend overview: Places were available to those wishing to learn some green wood skills over a weekend in Dunnet. The event was advertised locally and through the CWA network. Under the supervision and guidance of skilled craft makers from Wooplaw Community Woodland – in the Scottish Borders, delegates were put to work developing and constructing shave horses and pole lathes. This new equipment was constructed for Dunnet Forestry Trust using timber from site, and was the first event to take place in the newly built log cabin. Over the weekend delegates enjoyed good conversation and renewed community empowerment - with discussions leading towards the establishment of a greenwood group).