The Talking Cure: How Constitutional Argument Drives Constitutional Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neoliberalism and the Environmental Movement: Contemporary Considerations for the Counter Hegemonic Struggle Austen K

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2016 Neoliberalism and the Environmental Movement: Contemporary Considerations for the Counter Hegemonic Struggle Austen K. Bernier University of Colorado, Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Political Economy Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Bernier, Austen K., "Neoliberalism and the Environmental Movement: Contemporary Considerations for the Counter Hegemonic Struggle" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1013. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neoliberalism and the Environmental Movement: Contemporary Considerations for the Counter- Hegemonic Struggle By Austen K. Bernier University of Colorado at Boulder A Thesis Submitted to the University of Colorado at Boulder in partial fulfillment of the requirements to receive Honors designation in Environmental Studies May 2016 Thesis Advisors: Liam Downey, Department of Sociology, Committee Chair David Ciplet, Department of Environmental Studies Dale Miller, Department of Environmental Studies © 2016 by Austen Bernier All rights reserved ii Abstract This thesis proposes a conceptual framework for understanding how neoliberalism has decreased the ability of environmental movements to manifest changes in political economic structure or spur state action on environmental issues that might be antagonistic to the neoliberal order. Karl Marx and Karl Polanyi have developed reputable theories that describe social movements as exercising a degree of control over political economy. -

The Misrepresented Road to Madame President: Media Coverage of Female Candidates for National Office

THE MISREPRESENTED ROAD TO MADAME PRESIDENT: MEDIA COVERAGE OF FEMALE CANDIDATES FOR NATIONAL OFFICE by Jessica Pinckney A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government Baltimore, Maryland May, 2015 © 2015 Jessica Pinckney All Rights Reserved Abstract While women represent over fifty percent of the U.S. population, it is blatantly clear that they are not as equally represented in leadership positions in the government and in private institutions. Despite their representation throughout the nation, women only make up twenty percent of the House and Senate. That is far from a representative number and something that really hurts our society as a whole. While these inequalities exist, they are perpetuated by the world in which we live, where the media plays a heavy role in molding peoples’ opinions, both consciously and subconsciously. The way in which the media presents news about women is not always representative of the women themselves and influences public opinion a great deal, which can also affect women’s ability to rise to the top, thereby breaking the ultimate glass ceilings. This research looks at a number of cases in which female politicians ran for and/or were elected to political positions at the national level (President, Vice President, and Congress) and seeks to look at the progress, or lack thereof, in media’s portrayal of female candidates running for office. The overarching goal of the research is to simply show examples of biased and unbiased coverage and address the negative or positive ways in which that coverage influences the candidate. -

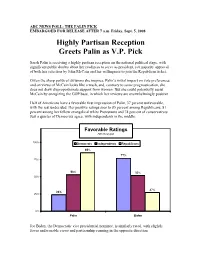

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

San Mateo County

san mateo county the newsletter for the Libertarian Party of San Mateo County independence day 2013 image: Robert Santorelli jefferson weeping by Judge Andrew Napolitano Do you have more personal liberty today than on the Fourth of July 2012? When Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, he used language that has become iconic. He wrote that we are endowed by our Creator with certain inalienable rights, and among them are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Not only did he write those words, but the first Congress adopted them unanimously, and they are still the law of the land today. By acknowledging that our rights are inalienable, Jefferson’s words and the first federal statute recognize that our rights come from our humanity – from within us – and not from the government. The government the Framers gave us was not one that had the power and ability to decide how much freedom each of us should have, but rather one in which we individually and then collectively decided how much power the government should have. That, of course, is also recognized in the Declaration, wherein Jefferson wrote that the government derives its powers from the consent of the governed. To what governmental powers may the governed morally consent contents in a free society? We can consent to the powers necessary to protect us from force and fraud, and to the means of revenue to pay for a government to exercise those powers. But no one can jefferson weeping ........... 111 consent to the diminution of anyone else’s natural rights, because, contact us ……….................... -

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters SUPRC Field

Suffolk University Virginia General Election Voters AREA N= 600 100% DC Area ........................................ 1 ( 1/ 98) 164 27% West ........................................... 2 51 9% Piedmont Valley ................................ 3 134 22% Richmond South ................................. 4 104 17% East ........................................... 5 147 25% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. We are calling Virginia households statewide. Would you be willing to spend three minutes answering some brief questions? <ROTATE> or someone in that household). N= 600 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/105) 600 100% GEND RECORD GENDER N= 600 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/106) 275 46% Female ......................................... 2 325 54% S2 S2. Thank You. How likely are you to vote in the Presidential Election on November 4th? N= 600 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/107) 583 97% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 17 3% Not very/Not at all likely ..................... 3 0 0% Other/Undecided/Refused ........................ 4 0 0% Q1 Q1. Which political party do you feel closest to - Democrat, Republican, or Independent? N= 600 100% Democrat ....................................... 1 ( 1/110) 269 45% Republican ..................................... 2 188 31% Independent/Unaffiliated/Other ................. 3 141 24% Not registered -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Historical Log of Judicial Appointments 1959-Present Candidates Nominated Appointed 1959 - Supreme Court - 3 New Positions William V

Historical Log of Judicial Appointments 1959-Present Candidates Nominated Appointed 1959 - Supreme Court - 3 new positions William V. Boggess William V. Boggess John H. Dimond Robert Boochever Robert Boochever Walter Hodge J. Earl Cooper John H. Dimond Buell A. Nesbett** Edward V. Davis Walter Hodge* 1959 by Governor William Egan John H. Dimond M.E. Monagle John S. Hellenthal Buell A. Nesbett* Walter Hodge * nominated for Chief Justice Verne O. Martin M.E. Monagle Buell A. Nesbett Walter Sczudlo Thomas B. Stewart Meeting Date 7/16-17/1959 **appointed Chief Justice 1959 - Ketchikan/Juneau Superior - 2 new positions Floyd O. Davidson E.P. McCarron James von der Heydt Juneau James M. Fitzgerald Thomas B. Stewart Walter E. Walsh Ketchikan Verne O. Martin James von der Heydt 1959 by Governor William Egan E.P. McCarron Walter E. Walsh Thomas B. Stewart James von der Heydt Walter E. Walsh Meeting Date 10/12-13/1959 1959 - Nome Superior - new position James M. Fitzgerald Hubert A. Gilbert Hubert A. Gilbert Hubert A. Gilbert Verne O. Martin 1959 by Governor William Egan Verne O. Martin James von der Heydt Meeting Date 10/12-13/1959 1959 - Anchorage Superior - 3 new positions Harold J. Butcher Harold J. Butcher J. Earl Cooper Henry Camarot J. Earl Cooper Edward V. Davis J. Earl Cooper Ralph Ralph H. Cottis James M. Fitzgerald H. Cottis Roger Edward V. Davis 1959 by Governor William Egan Cremo Edward James M. Fitzgerald V. Davis James Stanley McCutcheon M. Fitzgerald Everett Ralph E. Moody W. Hepp Peter J. Kalamarides Verne O. Martin Stanley McCutcheon Ralph E. -

Kruzelnick V. Napolitano Summons & Complaint

ESX-L-006413-20 09/28/2020 9:56:03 AM Pg 1 of 19 Trans ID: LCV20201705443 ESX-L-006413-20 09/28/2020 9:56:03 AM Pg 2 of 19 Trans ID: LCV20201705443 DIEGO O. BARROS, ESQ, 182412017 JOSEPH & NORINSBERG, LLC 110 East 59th Street, Suite 3200 New York, New York 10022 Tel: (212) 227-5700 Fax: (212) 656-1889 Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Plaintiff --------------------------------------------------------------------X JAMES KRUZELNICK, SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY LAW DIVISION ESSEX COUNTY Plaintiff, Docket No.: -against- COMPLAINT ANDREW NAPOLITANO, JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Defendant. --------------------------------------------------------------------X Plaintiff JAMES KRUZELNICK, by his attorneys JOSEPH & NORINSBERG, LLC, brings this action against defendant ANDREW NAPOLITANO, alleging, on personal knowledge as to him and on information and belief as to all other matters, as follows: JURY DEMAND 1. Plaintiff demands a trial by jury on all issues so triable. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2. This Court has personal jurisdiction over the Defendant in that on the date of the incidents described herein, defendant owned real property in the State of New Jersey, committed the unlawful acts alleged herein at said property, and is subject to the Court’s Jurisdiction. 3. This Court has jurisdiction over this action because the amount of damages Plaintiff seeks exceeds the jurisdictional limits of all lower courts which would otherwise have jurisdiction. 1 ESX-L-006413-20 09/28/2020 9:56:03 AM Pg 3 of 19 Trans ID: LCV20201705443 4. Venue for this action is proper in the County of Sussex, pursuant to R. 4:3-2 in that venue is properly laid in the county in which the cause of action arose. -

Originalism's Curiously Triumphant Death: the Interpenetration of Aspirationalism and Historicism in U.S. Constitutional Devel

[forthcoming in Problema Anuario de Filosofía y Teoría del Derecho (Universida National Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM)), Mexico City, Mexico (January 2017)] Originalism’s Curiously Triumphant Death: The Interpenetration of Aspirationalism and Historicism in U.S. Constitutional Development Ken I. Kersch∗ As someone preoccupied with the nature and processes of U.S. constitutional development from an empirical, positivist as opposed to a prescriptive, normative perspective – in is rather than ought -- my interest in contemporary constitutional theory of the sort practiced at a high level by Jim Fleming is oblique. I care more about history than theories of justice, about how the Constitution has actually been read to structure public (and private) authority in the U.S. over time than about justifying either the “best” readings of the parameters of that authority generally, or worrying in particularly about what theory of interpretation can justify a judge in exercising his or her purportedly problematic “countermajoritarian” powers of judicial review to hold a legislation null and void on the grounds that it contravenes the nation’s fundamental law.1 When I shake my head “yes” about constitutional theory, it is thus most immediately over what Michael Dorf identifies as the “eclectic accounts” of Phillip Bobbitt and Richard Fallon, scholars who find, usefully, but not surprisingly, that over the long course of American history, judges have used an array of “modalities,” or types of arguments, in publicly justifying their decisions in their judicial opinions.2 If one moves beyond judicial opinions to ∗ Professor of Political Science, Boston College. This article was previously published in the U.S. -

CV in PDF Format

PROFESSOR TODD J. ZYWICKI GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION PROFESSOR OF LAW GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW 3301 N. FAIRFAX DR. ARLINGTON, VA 22201 703-993-9484 [email protected] Web Page: http://mason.gmu.edu/~tzywick2/ PUBLICATIONS BOOKS CONSUMER CREDIT AND THE AMERICAN ECONOMY (with Thomas Durkin, Gregory Elliehausen, and Michael Staten), (Oxford University Press, 2014). PUBLIC CHOICE CONCEPTS AND APPLICATIONS IN LAW (with Maxwell Stearns) (West Publishing, 2009). Editor, The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity, 10 SUPREME COURT ECONOMIC REVIEW (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. 278 pp. ISBN: 0-226-99962-9). • Reviewed by Professor William A. Fischel, 14(6) LAW AND POLITICS BOOK REV. 493-97 (June 2004). ARTICLES AND BOOK CHAPTERS Bruno Leoni's Legacy and Continued Relevance, __ J. PRIVATE ENTERPRISE __ (Forthcoming 2015). Commentary on CFPB Report: Data Point: Checking Account Overdraft (with G. Michael Flores). Price Controls on Payment Card Interchange Fees: The U.S. Experience (with Geoffrey Manne and Julian Morris), ICLE Financial Regulatory Research Program White Paper 2014-2 (2014). Behavior, Paternalism, and Policy: Evaluating Consumer Financial Protection, __ NYU J. L. & LIBERTY __ (forthcoming 2014). Keynote Address: Is There a George Mason School of Law and Economics? __ J. LAW, ECONOMICS & POLICY __ (Forthcoming 2014). Uncertainty, Evolution, and Behavioral Economic Theory (with Geoffrey Manne), __ J. LAW, ECONOMICS & POLICY __ (Forthcoming 2014). Overdraft Protection and Consumer Protection: A Critique of the CFPB's Analysis of Overdraft Programs (with G. Michael Flores and Brian M. Deignan), 33(3) BANKING AND FINANCIAL SERVICES POLICY REPORT 10 (March 2014). The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, in PERSPECTIVES ON DODD-FRANK AND FINANCE (Forthcoming 2014, MIT Press). -

Corporatism, Informality and Democracy in the Streets of Mexico City

Corporatism, Informality and Democracy in the Streets of Mexico City Enrique de la Garza Toledo, Autonomous Metropolitan University, Mexico José Luis Gayosso Ramírez, Autonomous University of Querétaro, Mexico Leticia Pogliaghi, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico ABSTRACT While the end of corporatism has been frequently announced, we argue that in Mexico it persists under contemporary neo-liberalism, albeit with new characteristics. To explore these characteristics, we use the concept of corporatism in a broader sense. That is, we assume that it not only involves relationships between trade unions, business associations and the state, but also with other civil society organisations. For our study, this includes informal worker organisations, in particular of taxi drivers and street vendors. We analyse these organisations, their relationship with the work itself (especially the occupation of public space) and their linkages with local government. We conclude that while some organisations remain independent of government control, many are imbricated in corporate relationships with the state, giving rise to an informal corporatism. Finally, we reflect on the special features this informal corporatism shows. KEY WORDS Corporatism; informality; work conditions; political relationships; democracy Introduction The issue of corporatism was widely discussed during the 1970s and 1980s, based on the famous article by Schmitter (1979). Such was its impact that it inaugurated a wholesale change in political scientists' conceptualisation of governability, as well as in the study of the relationship between politics and the economy in capitalism (Wiarda, 2004). With the arrival of neo-liberalism, it was suggested that corporatism would be exhausted when it came into conflict with the conceptions of economic self-regulation and the quest for equilibrium (Wiarda, 2009).