Outsiderdom, Myths and Collective Memory in the Life and Works of Wilfred Owen Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Britain, the Two World Wars and the Problem of Narrative

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Historical Journal provided by Apollo Great Br itain, the Two World Wars and the Problem of Narrative Journal: The Historical Journal Manuscript ID HJ-2016-005.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Period: 1900-99, 2000- Thematic: International Relations, Military, Cultural, Intellectual Geographic: Britain, Europe, Continental Cambridge University Press Page 1 of 60 The Historical Journal Britain, the Two World Wars and the Problem of Narrative BRITAIN, THE TWO WORLD WARS AND THE PROBLEM OF NARRATIVE: PUBLIC MEMORY, NATIONAL HISTORY AND EUROPEAN IDENTITY* David Reynolds Christ’s College, Cambridge So-called ‘memory booms’ have become a feature of public history, as well as providing golden opportunities for the heritage industry. Yet they also open up large and revealing issues for professional historians, shedding light on how societies conceptualize and understand their pasts.1 This article explores the way that British public discourse has grappled with the First and Second World Wars. At the heart of the British problem with these two defining conflicts of the twentieth century is an inability to construct a positive, teleological metanarrative of their overall ‘meaning’. By exploring this theme through historiography and memorialization, it is possible not merely to illuminate Britain’s self-understanding of its twentieth-century history, but also to shed light on the country’s contorted relationship with ‘Europe’, evident in party politics and public debate right down to the ‘Brexit’ referendum of 2016. The concept of mastering the past ( Vergangenheitsbewältigung ) originated in post-1945 West Germany as that country tried to address the horrendous legacies of Nazism. -

The Glass Case Modern Literature Published After 1900

The Glass Case Modern Literature Published After 1900 On-Line Only: Catalogue # 209 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] The Glass Case: Modern Literature Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com or www.ABAA.org . 1. ABBEY, Edward. DESERT SOLITAIRE, A season in the wilderness. NY: McGraw-Hill, (1968). First Edition. 8vo, pp. 269. Drawings by Peter Parnall. A nice copy in little nicked dj. Scarce. [38528] $1,500.00 A moving tribute to the desert, the personal vision of a desert rat. The author's fourth book and his first work of nonfiction. This collection of meditations by then park ranger Abbey in what was Arches National Monument of the 1950s was quietly published in a first edition of 5,000 copies ONE OF 10 COPIES, AUTHOR'S FIRST BOOK 2. ADAMS, Leonie. THOSE NOT ELECT. NY: Robert M. McBride, 1925. First Edition. -

Christopher Isherwood Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pk0gr7 No online items Christopher Isherwood Papers Finding aid prepared by Sara S. Hodson with April Cunningham, Alison Dinicola, Gayle M. Richardson, Natalie Russell, Rebecca Tuttle, and Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2, 2000. Updated: January 12, 2007, April 14, 2010 and March 10, 2017 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Christopher Isherwood Papers CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Christopher Isherwood Papers Dates (inclusive): 1864-2004 Bulk dates: 1925-1986 Collection Number: CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 Creator: Isherwood, Christopher, 1904-1986. Extent: 6,261 pieces, plus ephemera. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of British-American writer Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), chiefly dating from the 1920s to the 1980s. Consisting of scripts, literary manuscripts, correspondence, diaries, photographs, ephemera, audiovisual material, and Isherwood’s library, the archive is an exceptionally rich resource for research on Isherwood, as well as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and others. Subjects documented in the collection include homosexuality and gay rights, pacifism, and Vedanta. Language: English. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department, with two exceptions: • The series of Isherwood’s daily diaries, which are closed until January 1, 2030. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Accord

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON TARIFFS AND TRADE MIN(86)/INF/3 ACCORD GENERAL SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ET LE COMMERCE 17 September 1986 ACUERDO GENERAL SOBRE ARANCELES ADUANEROS Y COMERCIO Limited Distribution CONTRACTING PARTIES PARTIES CONTRACTANTES PARTES CONTRATANTIS Session at Ministerial Session à l'échelon Periodo de sesiones a nivel Level ministériel ministerial 15-19 September 1986 15-19 septembre 1986 15-19 setiembre 1986 LIST OF REPRESENTATIVES LISTE DES REPRESENTANTS LISTA DE REPRESENTANTES Chairman: S.E. Sr. Enrique Iglesias Président; Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores Présidente; de la Republica Oriental del Uruguay ARGENTINA Représentantes Lie. Dante Caputo Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto » Dr. Juan V. Sourrouille Ministro de Economia Dr. Roberto Lavagna Secretario de Industria y Comercio Exterior Ing. Lucio Reca Secretario de Agricultura, Ganaderïa y Pesca Dr. Bernardo Grinspun Secretario de Planificaciôn Dr. Adolfo Canitrot Secretario de Coordinaciôn Econômica 86-1560 MIN(86)/INF/3 Page 2 ARGENTINA (cont) Représentantes (cont) S.E. Sr. Jorge Romero Embajador Subsecretario de Relaciones Internacionales Econômicas Lie. Guillermo Campbell Subsecretario de Intercambio Comercial Dr. Marcelo Kiguel Vicepresidente del Banco Central de la Republica Argentina S.E. Leopoldo Tettamanti Embaj ador Représentante Permanante ante la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas en Ginebra S.E. Carlos H. Perette Embajador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la Republica Oriental del Uruguay S.E. Ricardo Campero Embaj ador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la ALADI Sr. Pablo Quiroga Secretario Ejecutivo del Comité de Politicas de Exportaciones Dr. Jorge Cort Présidente de la Junta Nacional de Granos Sr. Emilio Ramôn Pardo Ministro Plenipotenciario Director de Relaciones Econômicas Multilatérales del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto Sr. -

Edward Upward and the Novel of Politics

Edward Upward and the Novel of Politics ANTHONY ARBLASTER Edward Upward, novelist, has enjoyed a second, fictional or semi- fictional life in the writings of his contemporaries for half a century. Under the pseudonym of “Allen Chalmers”, given to him by Christo- pher Isherwood, he appears in the autobiographies of Isherwood (Lions and Shadows) and Stephen Spender (World Within World). But Chalmers’ first appearance is as a character in Isherwood’s very first novel, All the Conspirators, published in 1928. Did Upward himself really exist? In the 1930’s some stories and a short novel, Journey to the Border, were published under his name. But for twenty years between 1942 and 1962 Upward published nothing except for one early story, The Railway Accident, which he partly disowned, and which therefore appeared under the familiar pseudonym, with an introduc- tion, appropriately, by Isherwood, the inventor of “Allen Chalmers”. Like another writer of the ’thirties, Jean Rhys, Upward disappeared from public view for many years. He has since explained the relation between this long silence and his engagement with and painful dis- engagement from the Communist Party. This relationship is itself one main theme of the trilogy of novels published since 1962 under the overall title of The Spiral Ascent (Onward and Upward?). Even now that Upward can be perceived as a novelist in his own right, the relationship between Upward and Chalmers still flourishes in the material of the trilogy, as will be seen. Isherwood and Upward have enjoyed a kind of literary partnership, the most enduring among those writers who formed a recognisable group or generation in the 1930’s. -

Siegfried Sassoon

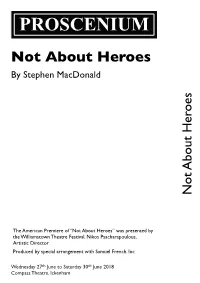

PROSCENIUM Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Not About Heroes About Not The American Premiere of “Not About Heroes” was presented by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Nikos Psacharapoulous, Artistic Director Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc Wednesday 27th June to Saturday 30th June 2018 Compass Theatre, Ickenham Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Siegfried Sassoon ..................................................... Ben Morris Wilfred Owen .................................................... James Stephen Directed by ........................................................ Richard Kessel Stage Manager .................................................. Keith Cochrane Assisted By ...................................................... Crystal Anthony Technical Assistance ....................................... Charles Anthony Lighting Operation ................................................ Roger Turner Sound Operation ................................................Richard Kessel The Action From a room in Sassoon’s country house in Wiltshire, late at night on 3rd November 1932, Sassoon re-lives incidents that happened between August 1917 and November 1918. In sequence they take place in: • A quiet corner of the Conservative Club in Edinburgh (3rd November 1917) • Two rooms in the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Nervous Disorders, Edinburgh (August-October 1917) • The countryside near Milnathort, Scotland (October 1917) • Owen’s room in Scarborough, Yorkshire (January 1918) • Sassoon’s room in the American -

SIBL. . V^'- ' / Proquest Number: 10096794

-TÂ/igSEOBSIAW p o e t s : A. CBIIXCÆJEaaMIBA!ElûIif--CÆJ^ POETRY '' ARD POETIC THEORY. “ KATHARIKE COOKE. M. P h i l . , SIBL. v^'- ' / ProQuest Number: 10096794 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10096794 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 SYNOPSIS. As the Introduction explains this thesis sets out to look at the Georgians* achievement in poetry in the light of their intentions as avowed in prose and their methods as exemplified hy their poems. This is chiefly a critical exercise hut history has heen used to clear away the inevitable distortion which results from looking at Georgian poetry after fifty years of Eliot- influenced hostility. The history of the movement is dealt with in Chapter 2. The next three chapters examine aspects of poetry which the Georgians themselves con sidered most interesting. Chapter 3 deals with form, Chapter 4 with diction and Chapter 5 with inspiration or attitude to subject matter. Chapter 6 looks at the aspect of Georgianism most commonly thought by later readers to define the movement, th a t is i t s subjects. -

Wilfred Owen

THE GREAT THE WAR POETRY OF POETS Wilfred Owen Read by Anton Lesser POETRY 1 Preface 1:09 2 From My Diary, July 1914 1:20 3 1914 1:13 4 The Send-off 1:17 5 The Letter 1:27 6 Arms and the Boy 0:49 7 Parable of the Old Men and the Young 1:13 8 Spring Offensive 3:02 9 The Chances 0:55 10 Futility 0:54 11 S. I. W. Self Inflicted Wound 3:23 12 Has Your Soul Sipped? 1:33 13 As Bronze May Be Much Beautified 0:49 14 It Was a Navy Boy 2:37 15 Inspection 0:55 16 Anthem for Doomed Youth 1:03 17 The Unreturning 1:06 18 Le Christianisme 0:31 19 Soldier’s Dream 0:45 20 At a Calvary Near the Ancre 0:54 21 Greater Love 1:37 22 The Last Laugh 1:09 23 Hospital Barge 1:13 24 Training 0:38 25 Schoolmistress 0:42 2 26 An Imperial Elegy 0:33 27 The Calls 1:57 28 On Seeing a Piece of Our Artillery Brought into Action 1:08 29 Exposure 3:18 30 Asleep 1:45 31 The Dead-Beat 1:30 32 Mental Cases 2:14 33 Conscious 1:24 34 The Show 2:15 35 Smile, Smile, Smile 1:42 36 Disabled 3:16 37 A Terre (Being the philosophy of many soldiers) 4:13 38 Beauty (Notes for an Unfinished poem) 1:56 39 Miners 1:38 40 Cramped in That Funnelled Hole 0:41 41 The Sentry 2:16 42 Dulce et Decorum est 1:52 43 Apologia pro Poemate Meo 2:19 44 Insensibility 2:45 45 The End 1:15 46 The Next War 1:10 47 Sonnet to My Friend – With an Identity Disc 1:05 48 Strange Meeting 3:28 49 On My Songs 0:58 Total time: 79:17 3 The Great Poets The WAR Poetry OF Wilfred Owen It would surely be impossible to name a witness and report faithfully on the horror poet more closely or completely identified of omnipresent death, and commitment with any historical event than Wilfred to protest against it with all the anger he Owen is with the First World War. -

The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry

The Hilltop Review Volume 9 Issue 2 Spring Article 4 June 2017 Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry Rebecca E. Straple Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Preferred Citation Style (e.g. APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) Chicago This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 14 Rebecca Straple Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry “Unburiable bodies sit outside the dug-outs all day, all night, the most execrable sights on earth: In poetry, we call them the most glorious.” – Wilfred Owen, February 4, 1917 Rebecca Straple Winner of the first place paper Ph.D. in English Literature Department of English Western Michigan University [email protected] ANY critics of poetry written during World War I see a clear divide between poetry of the early and late years of the war, usually located after the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Af- ter this event, poetic trends seem to move away from odes Mto courageous sacrifice and protection of the homeland, toward bitter or grief-stricken verses on the horror and pointless suffering of the conflict. This is especially true of poetry written by soldier poets, many of whom were young, English men with a strong grounding in Classical literature and languages from their training in the British public schooling system. -

The Poetry of Siegfried Sassoon

Durham E-Theses The poetry of siegfried sassoon Cumming, Deryck How to cite: Cumming, Deryck (1969) The poetry of siegfried sassoon, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10240/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE POEPRY OF SIEGPEIIED SASSOON Deryck Gtumning M.A. thesis University of Durham The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be. acknowledged. page Early Poems 1 II War Poems, 1915-1917 20 III Counter-Attack 64 IV Picture Show 102 V Poems of the Twenties 115 VI Poems of the Thirties 135 VII Poems of the Fifties I53 VIII Conclusion 167 Bibliography _Ch_cvpt_Gr_ On^ EAHLY POEflS Siegfried. S-J5soon "born in I8865 the cccond of thrrr sons of Alfred Ezrr, Sr.ssoon r,nd Thcrcsr. -

Ergotherapy and the Doctor Who Cured Wilfred Owen

‘Re-education’, ergotherapy and the doctor who cured Wilfred Owen The end of 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of Wilfred Owen’s war poems being published posthumously.1 A quarter of Owen’s poems and fragments were written or updated in late 1917 when he was a ‘shell-shock’ patient in Edinburgh’s Craiglockhart War Hospital. Here he penned his most remembered verse. Without Craiglockhart and the care of Edinburgh doctor, Dr Arthur John Brock, we may never have read Owen’s words on ‘the pity of war’.2 A century on, Brock’s ‘ergotherapy’ treatments may have resonance and applicability as we care for mental health issues emanating from current global crises. In 1917 Owen saw action in the Somme area of the Western Front. He became a casualty having fallen into a shell hole. Recovering from concussion he was later blown up by a trench mortar and reportedly spent days unconscious. On regaining consciousness, Owen found himself surrounded by the remains of a fellow officer. Owen was transferred to one of the two reception centres for ‘shell-shock’, the Royal Victoria Hospital (the Welsh Hospital, Netley), where he was diagnosed as suffering from ‘war neuroses’ by doctors there. He was then moved to one of Britain’s six ‘shell-shock’ hospitals for officers - Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh. There he was placed under the care of Dr Brock. Brock believed in purging what caused the shock before a programme of ‘re-education’3 whereby patients were returned to normal living and working. This involved ‘ergotherapy’ activities. ‘Ergotherapy’ is the use of physical exertion as a treatment4 or as Brock described it more widely, “cure by functioning.”5 His prescribed activities were both physical and active artistic engagement, stimulating the body and mind. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm.