VOLUME XXI 1996 Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intra-Party Democracy in Ghana's Fourth Republic

Journal of Power, Politics & Governance December 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3 & 4, pp. 57-75 ISSN: 2372-4919 (Print), 2372-4927 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jppg.v2n3-4a4 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/jppg.v2n3-4a4 Intra-Party Democracy in Ghana’s Fourth Republic: the case of the New Patriotic Party and National Democratic Congress Emmanuel Debrah1 Abstract It is argued that political parties must be internally democratic in order to promote democracy within society. This article examines the extent to which the two leading Ghanaian political parties, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC) that have alternated power, nurtured and promoted democratic practices within their internal affairs. While the parties have democratized channels for decision-making and choosing of leaders and candidates, the institutionalization of patron-client relationships has encouraged elite control, violence and stifled grassroots inclusion, access to information, fair competition and party cohesion. A multifaceted approach including the adoption of deliberative and decentralized decision-making, the mass-voting and vertical accountability would neutralize patronage tendencies for effective intra-party democracy. Keywords: Intra-party democracy; leadership and candidate selection; patronage politics; political parties; Ghana 1. Introduction Ghana made a successful transition from authoritarian to democratic rule in 1992. Since then, democratic governance has been firmly entrenched. Of the forces that have shaped Ghana’s democracy, political parties have been acknowledged (Debrah and Gyimah-Boadi, 2005). They have not only offered the voters choices between competing programs at elections but also provided cohesion to the legislature. -

Kwame Nkrumah and the Pan- African Vision: Between Acceptance and Rebuttal

Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy & International Relations e-ISSN 2238-6912 | ISSN 2238-6262| v.5, n.9, Jan./Jun. 2016 | p.141-164 KWAME NKRUMAH AND THE PAN- AFRICAN VISION: BETWEEN ACCEPTANCE AND REBUTTAL Henry Kam Kah1 Introduction The Pan-African vision of a United of States of Africa was and is still being expressed (dis)similarly by Africans on the continent and those of Afri- can descent scattered all over the world. Its humble origins and spread is at- tributed to several people based on their experiences over time. Among some of the advocates were Henry Sylvester Williams, Marcus Garvey and George Padmore of the diaspora and Peter Abrahams, Jomo Kenyatta, Sekou Toure, Julius Nyerere and Kwame Nkrumah of South Africa, Kenya, Guinea, Tanza- nia and Ghana respectively. The different pan-African views on the African continent notwithstanding, Kwame Nkrumah is arguably in a class of his own and perhaps comparable only to Mwalimu Julius Nyerere. Pan-Africanism became the cornerstone of his struggle for the independence of Ghana, other African countries and the political unity of the continent. To transform this vision into reality, Nkrumah mobilised the Ghanaian masses through a pop- ular appeal. Apart from his eloquent speeches, he also engaged in persuasive writings. These writings have survived him and are as appealing today as they were in the past. Kwame Nkrumah ceased every opportunity to persuasively articulate for a Union Government for all of Africa. Due to his unswerving vision for a Union Government for Africa, the visionary Kwame Nkrumah created a microcosm of African Union through the Ghana-Guinea and then Ghana-Guinea-Mali Union. -

Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-22-2019 Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality Emmanuella Amoh Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the African History Commons Recommended Citation Amoh, Emmanuella, "Kwame Nkrumah, His Afro-American Network and the Pursuit of an African Personality" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1067. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1067 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KWAME NKRUMAH, HIS AFRO-AMERICAN NETWORK AND THE PURSUIT OF AN AFRICAN PERSONALITY EMMANUELLA AMOH 105 Pages This thesis explores the pursuit of a new African personality in post-colonial Ghana by President Nkrumah and his African American network. I argue that Nkrumah’s engagement with African Americans in the pursuit of an African Personality transformed diaspora relations with Africa. It also seeks to explore Black women in this transnational history. Women are not perceived to be as mobile as men in transnationalism thereby underscoring their inputs in the construction of certain historical events. But through examining the lived experiences of Shirley Graham Du Bois and to an extent Maya Angelou and Pauli Murray in Ghana, the African American woman’s role in the building of Nkrumah’s Ghana will be explored in this thesis. -

Fritts, Robert E

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project ROBERT E. FRITTS Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: September 8, 1999 Copyright 200 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS European Affairs 19 9-1962 Luxembourg 1962-1964 To(yo, Japan 196 -1968 East Asian Affairs ,EA-, Japan Des( 1968-19.1 Foreign Service 0nstitute ,FS0-, Economics 1ourse 19.1 Ja(arta, 0ndonesia2 Economic Officer 19.2-19.3 4hartoum, Sudan2 19.3-19.4 4igali, Rwanda 19.4-19.6 East Asian Affairs ,EA- 19.6-19.9 1onsular Affairs ,1A- 19.9-1982 Accra, 7hana 1983-1986 8illiamsburg, 9irginia, The 1ollege of 8illiam and Mary 1986-198. Office of 0nspector 7eneral - Team Leader 198.-1989 INTERVIEW $: Today is the 8th of September 1999. This is an interview with Robert E. Fritts. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, and 1 I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. Bob and I are old friends. Could you tell me when, where you were born and something about your family- FR0TTS2 0 was born in 1hicago, 0llinois, in 1934. 0 had the good fortune of being raised in the 1hicago suburb of Oa( Par(, then labeled as the "largest village in the world." 0n contrast to a Foreign Service career, we didn't move. 0 went through the entire Oa( Par( public school system ,(-12-. My parents were born and grew up in St. Joseph, 0llinois, a very small town near 1hampaign-Urbana, home of the University of 0llinois. My father, the son of a railroad section trac( foreman, was poor, but wor(ed his way through the University of 0llinois to gain a mechanical engineering degree in 1922. -

Program for the 23Rd Conference

rd 23 Annual Cheikh Anta Diop International Conference “Fundamentals and Innovations in Afrocentric Research: Mapping Core and Continuing Knowledge of African Civilizations” October 7-8, 2011 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7 Registration 7:30am-5:00pm Drum Call 8:15am-8:30am Opening Ceremony and Presentation of Program 8:30am-9:00am Panel 1 - Education Primers and Educational Formats for Proficiency in African Culture 9:00am-10:10am 1) Dr. Daphne Chandler “Martin Luther King, Jr. Ain’t All We Got”: Achieving and Maintaining Cultural Equilibrium in 21st Century Western-Centered Schools 2) Dr. Nosakare Griffin-El Trans-Defining Educational Philosophy for People of Africana Descent: Towards the Transconceptual Ideal of Education 3) Dr. George Dei African Indigenous Proverbs and the Instructional and Pedagogic Relevance for Youth Education Locating Contemporary Media and Social Portrayals of African Agency 10:15am-11:25am 1) Dr. Ibram Rogers A Social Movement of Social Movements: Conceptualizing a New Historical Framework for the Black Power Movement 2) Dr. Marquita Pellerin Challenging Media Generated Portrayal of African Womanhood: Utilizing an Afrocentric Agency Driven Approach to Define Humanity 3) Dr. Martell Teasley Barrack Obama and the Politics of Race: The Myth of Post-racism in America Keynote Address Where Myth and Theater Meet: Re-Imaging the Tragedy of Isis and Osiris 11:30am-12:15pm Dr. Kimmika Williams‐Witherspoon Lunch 12:15pm-1:45pm Philosophy and Practice of Resurgence and Renaissance 1:45pm-3:00pm 1)Abena Walker Ancient African Imperatives to Facilitate a Conscious Disconnect from the Fanatical Tyranny of Imperialism: The Development of Wholesome African Objective for Today’s Africans 2) Kwasi Densu Omenala (Actions in Accordance With the Earth): Towards the Development of an African Centered Environmental Philosophy and Its Implications for Africana Studies 3) Dr. -

Africology 101: an Interview with Scholar Activist Molefi Kete Asante

Africology 101: An Interview with Scholar Activist Molefi Kete Asante by Itibari M. Zulu, Th.D. Editor, The Journal of Pan African Studies Molefi Kete Asante (http://www.asante.net) is Professor of African American Studies in the Department of African American Studies at Temple University. He is considered one of the most distinguished contemporary scholars, and has published 66 books, among the most recent being An Afrocentric Manifesto: Toward an African Renaissance and The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony. He has published more scholarly books than any contemporary African author and has been recognized as one of the ten most widely cited African Americans. Dr. Asante completed his M.A. at Pepperdine University, received his Ph.D. from the University of California, Los Angeles at the age of 26 and was appointed a full professor at the age of 30 at the State University of New York at Buffalo; and notwithstanding, at Temple University he created the first Ph.D. program in African American Studies in 1987; he has directed more than 125 Ph.D. dissertations; written more than 300 articles for journals and magazines; he is the founding editor of The Journal of Black Studies (1969); the founder of the theory of Afrocentricity, and in 1995 he was made a traditional king, Nana Okru Asante Peasah, Kyldomhene of Tafo, Akyem, Ghana. Itibari M. Zulu ([email protected]) is the editor-in-chief of The Journal of Pan African Studies, author of Exploring the African Centered Paradigm: Discourse and Innovation in African World Community Studies, editor of Authentic Voices: Quotations and Axioms from the African World Community, editor of the forthcoming book Africology: A Concise Dictionary, provost of Amen-Ra Theological Seminary, and vice president of the African Diaspora Foundation. -

Government Denies Existence of Political Prisoners

August 12, 1991 Ghana Government Denies Existence of Political Prisoners Minister Says Detainees "Safer" in Custody Introduction Ghana's ruling Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), chaired by Flt. Lt. Jerry Rawlings, has claimed -- for the third time in as many years -- that Ghana has no political prisoners. In a radio interview on May 31, Secretary for Foreign Affairs Obed Asamoah, argued that some detainees -- whom he characterized as "subversives" -- are being kept in custody for their own good. He added that if they were brought to trial, they would be convicted and executed. The first claim is deliberately misleading. Africa Watch knows of the existence of a number of detainees incarcerated in Ghana, though it is difficult to estimate the exact number in the light of government denials. One group -- of ten detainees -- was moved to different prisons on the same day -- January 14, 1991. One member of this group is known to have been held without charge or trial since November 1982. Their detentions have never been officially explained. The minister's argument that detainees are better protected in custody amounts to a manifest presumption of guilt, and makes it unlikely that any detainee in Ghana can now receive a fair trial. The government's denial is also contradicted by the publication on May 30 of a list of 76 "political prisoners and other detainees" by the opposition Movement for Freedom and Justice (MFJ). According to the MFJ's information at the time, none of the 76 had been charged or tried. The PNDC Secretary for the Interior, Nana Akuoku Sarpong, has characterized the list as a mixture of "lies and half truths," calculated to discredit the government. -

Understanding the Dynamics of Good Neighbourliness Under Rawlings and Kufuor

South African Journal of International Affairs ISSN: 1022-0461 (Print) 1938-0275 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsaj20 Understanding the dynamics of good neighbourliness under Rawlings and Kufuor Bossman E. Asare & Emmanuel Siaw To cite this article: Bossman E. Asare & Emmanuel Siaw (2018) Understanding the dynamics of good neighbourliness under Rawlings and Kufuor, South African Journal of International Affairs, 25:2, 199-217, DOI: 10.1080/10220461.2018.1481455 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2018.1481455 Published online: 02 Jul 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 125 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsaj20 SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS 2018, VOL. 25, NO. 2, 199–217 https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2018.1481455 Understanding the dynamics of good neighbourliness under Rawlings and Kufuor Bossman E. Asarea and Emmanuel Siawb aUniversity of Ghana, Accra, Ghana; bRoyal Holloway, University of London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS It is widely recognised that leadership influences relations between Ghana; Foreign Policy; neighbouring states in international affairs. This article seeks Rawlings; Kufour; good to further illuminate the relationship between leadership neighbourliness; personal idiosyncrasies and the nature of Ghana’s neighbour relations idiosyncracies in policymaking under Presidents Rawlings and Kufuor. The argument is that, while political institutionalisation and the international environment may influence neighbour relations to some degree, leader idiosyncrasy is an important intervening variable. Indeed, based on the findings, the international environment may have had less influence on Ghana’s neighbour relations in the period under study (1981–2008) than conventional wisdom suggests. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

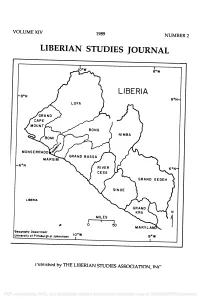

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L. -

Liberia-Human Rights-Fact Finding Mission Report-1998-Eng

Fact-Finding/Needs Assessment Mission to L ib e ria 11-16 May 1998 nal Commission of Jurists The International CommLfdion of Jur'uftj (IC J) permits free reproduction of extracts from any of its publications provided that due acknowledgement is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extract is sent to its headquar ters at the following address: International Communion of Juridtd (ICJ) P.O.Box 216 81 A, avenue de Chatelaine CH - 1219 Chatelaine/Geneva Switzerland Telephone : (4122) 97958 00; Fax : (4122) 97938 01 e-mail: [email protected] C o n t e n t s Introduction ................................................................................. 7 Historical Background................................................................ 8 Structure of the State................................................................... 11 The Executive........................................................................ 11 The Legislature...................................................................... 11 The Judiciary.......................................................................... 12 The Courts and the Application of Substantive Laws........... 12 Judicial Independence................................................................ 13 Legal and Judicial Protection of Human Rights .................... 14 The Bar and related Bodies ....................................................... 17 The Role of Local Non-Governmental Organizations........... 18 International Governmental and Non-Governmental Organizations ................................. -

The Speculative Fiction of Octavia Butler and Tananarive Due

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 An Africentric Reading Protocol: The pS eculative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due Tonja Lawrence Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Lawrence, Tonja, "An Africentric Reading Protocol: The peS culative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 198. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. AN AFRICENTRIC READING PROTOCOL: THE SPECULATIVE FICTION OF OCTAVIA BUTLER AND TANANARIVE DUE by TONJA LAWRENCE DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: COMMUNICATION Approved by: __________________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY TONJA LAWRENCE 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my children, Taliesin and Taevon, who have sacrificed so much on my journey of self-discovery. I have learned so much from you; and without that knowledge, I could never have come this far. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the direction of my dissertation director, help from my friends, and support from my children and extended family. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation director, Dr. Mary Garrett, for exceptional support, care, patience, and an unwavering belief in my ability to complete this rigorous task.