School-Based Deworming in Oyo State, Nigeria Process Monitoring and Coverage Validation Report October 2018 Round

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’S Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y

Programme Division Towards Better Programming Guidelines Series AA ManualManual onon SchoolSchool SanitationSanitation andand HygieneHygiene In Collaboration with Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 September 1998 A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’s Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unicef.org A publication of UNICEF/Programme Division Water, Environment and Sanitation ID No. UNICEF/PD/WES/98-5 This School Sanitation and Hygiene Manual is one of the Technical Guidelines Series prepared by the Water, Environment and Sanitation Section, Programme Division, UNICEF, in collaboration with the IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, The Netherlands. Titles of other publications in this series are printed on the inside back cover of this Manual. For further information contact: Water, Environment and Sanitation Section Programme Division, UNICEF 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 Tel (212) 824-6669; Fax: (212) 824-6480 e-mail: [email protected] IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre P.O. Box 93190 2509 AD The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 (0)70 3068930, Fax: +31 (0)670 3589964, E-mail: [email protected] Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Towards Better Programming A manual on school sanitation and hygiene United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre 1998 Table of contents Acknowledgements vii Preface iix 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Importance of school sanitation and Hygiene 1 1.2 Purpose and set-up of the manual 3 1.3 Scope of the manual 3 1.4 For whom are this manual intended 4 1.5 UNICEF's role as catalyst 4 1.6 Who contributed to this manual 4 PART I SCHOOL SANITATION AND HYGIENE AT DISTRICT AND NATIONAL LEVEL 2. -

A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’S Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y

Programme Division Towards Better Programming Guidelines Series AA ManualManual onon SchoolSchool SanitationSanitation andand HygieneHygiene In Collaboration with Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 September 1998 A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’s Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unicef.org A publication of UNICEF/Programme Division Water, Environment and Sanitation ID No. UNICEF/PD/WES/98-5 This School Sanitation and Hygiene Manual is one of the Technical Guidelines Series prepared by the Water, Environment and Sanitation Section, Programme Division, UNICEF, in collaboration with the IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, The Netherlands. Titles of other publications in this series are printed on the inside back cover of this Manual. For further information contact: Water, Environment and Sanitation Section Programme Division, UNICEF 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 Tel (212) 824-6669; Fax: (212) 824-6480 e-mail: [email protected] IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre P.O. Box 93190 2509 AD The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 (0)70 3068930, Fax: +31 (0)670 3589964, E-mail: [email protected] Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Towards Better Programming A manual on school sanitation and hygiene United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre 1998 Table of contents Acknowledgements vii Preface iix 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Importance of school sanitation and Hygiene 1 1.2 Purpose and set-up of the manual 3 1.3 Scope of the manual 3 1.4 For whom are this manual intended 4 1.5 UNICEF's role as catalyst 4 1.6 Who contributed to this manual 4 PART I SCHOOL SANITATION AND HYGIENE AT DISTRICT AND NATIONAL LEVEL 2. -

Menstrual Hygiene Management Policy

REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF HEALTH MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT POLICY 2019-2030 a REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF HEALTH MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT POLICY 2019-2030 Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................v Preface .................................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgement ............................................................................................................................. vii Acronyms/Abbreviations .................................................................................................................viii Glossary/Definition of Terms............................................................................................................ x 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Situational Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Information, Knowledge and Awareness on Menstruation ............................................ 1 1.1.2 Knowledge of and Access to Menstrual Management Products .................................. 2 1.1.3 MHM in Learning Institutions .............................................................................................. -

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit and Hygiene Sanitation, Water, Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit Let Girls Learn April 2017 Publication Number M0124 Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit Office of Global Health and HIV April 2017 Publication No. M0124 The Peace Corps is committed to providing access and reasonable accommodations to individuals with disabilities. Should you require this material in an alternate format, please contact the Office of Civil Rights and Diversity at 202-692-2139 or [email protected]. Acknowledgments The Peace Corps WASH in Schools Toolkit was developed by Janet Holt, public health program specialist, and Emily Hoppes, program support assistant, in the Office of Global Health and HIV (OGHH) in conjunction with the Peace Corps Let Girls Learn Program. Content was provided by Monique Widyono, gender specialist with Let Girls Learn in the Office of Overseas Programming and Training Support (OPATS). In addition, editing and publishing oversight was provided by Laura Pirocanac, strategic content and design manager, OPATS. Field input was provided by staff and Volunteers from Peace Corps/ Ghana, Peace Corps/Togo, and Peace Corps/Madagascar. Significant guidance was provided by the USAID/WASHplus Project led by FHI 360. The authors would also like to acknowledge the leadership and support provided by Shelley Smith, chief of programming and training in OGHH, and Krista Rigalo, program director of the Peace Corps Let Girls Learn Program. The Peace Corps gratefully acknowledges the talent and skills of the authors who provided authorization for use of their materials in this manual: USAID; WHO; GIZ; Mark Tiele, Westra Werkgroep Ontwikkelings Technieken, University of Twente; U.S. -

School-Based Deworming: a Planner’S Guide to Proposal Development for National School-Based Deworming Programs

School-based deworming: A planner’s guide to proposal development for national school-based deworming programs Conference Ready Edition Produced by Deworm the World with input from: The Partnership for Child Development, the World Bank, the Education for All–Fast Track Initiative, the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, the Ministries of Health and Education in The Gambia, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, Innovations for Poverty Action, Kenya Medical Research Institute, and Helen Keller International. © Deworm the World 2010 All rights reserved. Permission to reproduce any part of this document is required. Please contact: Deworm the World 1000 Thomas Jefferson Street NW Washington, D.C. 20007, USA. Telephone: +1-202-403-5714. Fax: +1-202-403-5994. Email: [email protected] For further information on worm control in school-age children please visit the following websites: www.dewormtheworld.org; www.schoolsandhealth.org; and www.who.int/wormcontrol/en/ How to use this guide This guide is intended to assist policymakers and planners in proposal writing and initial design for national school-based deworming programs. It is also a detailed aid for construction of an accompanying budget. Based around 8 Steps for developing a school-based deworming program the guide highlights all the key pieces of information which will be needed at the planning and proposal stage and how they should be used in designing the program. When planning a school-based deworming program or writing a proposal each step should be addressed and the relevant information sought. Where information or action is not available or concluded, the proposal and plan should include next steps for completion. -

Rethinking School Health: a Key Component of Education for All, Takes the Goal of EFA Further

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Human Development DIRECTIONS INDEVELOPMENT A Key Component of Education forAll ofEducation Component A Key Rethinking School Health Donald Bundy Rethinking School Health Rethinking School Health A Key Component of Education for All Donald Bundy © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 14 13 12 11 Preparation of this volume was led by staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The bound- aries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with com- plete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Standards for Schools in Low-Cost Settings

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Standards for Schools in Low-cost Settings Edited by: John Adams, Jamie Bartram, Yves Chartier, Jackie Sims WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data World Health Organization. Water, sanitation and hygiene standards for schools in low-cost settings Edited by John Adams, Jamie Bartram, Yves Chartier, Jackie Sims 1.Water supply — standards. 2.Water quality. 3.Sanitation — standards. 4.Hygiene — standards. 5.School health services — organization and administration. 6.Disease vectors. 7.Public policy. 8.Guidelines. 9.Developing countries. I.Adams, John. II.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154779 6 (NLM classification: WA 675) © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications — whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution — should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

WASH in Schools Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Is What Is Important for Good Health

WASH in Schools Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) is What is important for good health. Schools take simple, inexpensive steps to improve WASH WASH in facilities at their school, and healthy hygiene habits are taught, practised and CASE STUDY Schools? integrated into daily school routines. Wash in Schools In this project Live & Learn worked with schools on a bottom-up approach that demonstrates the impact of WASH in Schools on improved learning and student well-being. Live & Learn uses an adapted the UNICEF 3-Star Schools and Bottleneck Analysis approach. Improving health and education of Bottleneck analysis assumes that WASH in Schools problems can be conceptualized as a type of service delivery chain. The bottleneck is a point where services are restricted. Schools are children in Vanuatu provided with tools and skills to critically assess and act to improve their WASH services. The simplified bottom-up approach to collecting and analysing evidence for WASH at a school level implemented by L&L staff with partner schools lead to school WASH Committees establish plans to Live & Learn ran a successful four-year Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Schools improve toilets and hand-washing facilities in schools, improve teacher-led hygiene promotion in program in six urban schools, benefiting over 6000 students. The program was part of classes, improve peer-to-peer advocacy by students, strengthen engagement with local and national Ministries of Education. a broader program delivered with 18,000 students in Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Fiji and Vanuatu with funding from the the Australian Government through the “Western Pacific Sanitation Marketing & Innovation Program” funded by the Civil Society WASH Fund. -

The Situation of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Schools in the Pan-European Region

The situation of water, sanitation and hygiene in schools in the pan-European region By Valentina Grossi, Emanuel Klimschak, Andrea Rechenburg, Enkhtsetseg Shinee and Oliver Schmoll Abstract Adequate access to water, hygiene and sanitation (WASH) is every human’s and child’s right. Ensuring WASH accessibility in schools is encompassed in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and is a priority area under the Protocol on Water and Health to the 1992 Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes. This publication summarizes the status of WASH in schools in the pan-European region. Available evidence was retrieved from scientific literature, national and international surveys and a desk review of case studies. The data show general progress in WASH policies and targets, but a concurrent lack of translation of this progress into efficient improvement of WASH in schools. Gaps and challenges are found as a result of non-comprehensive standards, inefficient coordination and inadequate surveillance and monitoring indicators. Further, neglected disparities and inequalities are observed through the region. WASH conditions do not reflect policies’ aspirations and are not adequate to pupils’ needs, affecting their health, well-being and performance at school. The main challenges across the region are related in particular to inadequate cleanliness and provision of consumables, as well as maintenance of sanitation facilities and accessibility to safe drinking-water. Policy-making needs to be supported -

School-Based Deworming in Cross River State, Nigeria Process Monitoring and Coverage Validation Report, October 2018 Round

School-based Deworming in Cross River State, Nigeria Process Monitoring and Coverage Validation Report, October 2018 Round April 2019 Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 3.0 Methodology ................................................................................................................. 3 4.0 Results .......................................................................................................................... 5 4.1 Review of teacher training ........................................................................................ 5 4.2 Deworming Day assessment .................................................................................... 7 4.3 Community sensitization ....................................................................................... 10 4.4 School hygiene facilities .......................................................................................... 12 4.5 Coverage validation ................................................................................................. 13 5.0 Lessons Learned ......................................................................................................... 18 What worked well ......................................................................................................... 18 What needs to improve ............................................................................................... -

Return to Schoolplan

Return to School Plan Together.Again. September 2021 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................1 Preparation of Schools, Staff and Students ..................................................................................4 Plans for School Operations .............................................................................................................16 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................18 Appendix A: Newfoundland and Labrador Public Health Guidance for Return to School Kindergarten to Grade 12 ....................19 Appendix i: Guidance for Staff or Students Who Become Ill While in the School Setting ....................................35 Appendix ii: Hand Hygiene Guidance ................................................................37 Executive Summary The NL Back to School Plan for September 2021 prioritizes the safety and well-being of students and staff. It is a joint plan of the Provincial Department of Education, the Newfoundland and Labrador English School District (NLESD), and the Conseil scolaire francophone provincial de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador (CSFP). The following plan describes how NLESD and CSFP schools are expected to operate in the 2021- 2022 school year. This re-entry plan follows guidelines and recommendations outlined in the Newfoundland and Labrador Public Health Guidance -

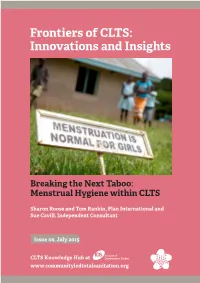

Frontiers of CLTS: Innovations and Insights

Frontiers of CLTS: Innovations and Insights Breaking the Next Taboo: Menstrual Hygiene within CLTS Sharon Roose and Tom Rankin, Plan International and Sue Cavill, Independent Consultant Issue 06, July 2015 CLTS Knowledge Hub at www.communityledtotalsanitation.org About the CLTS Knowledge Hub IDS has been working in support of Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) since its beginnings. CLTS has now become an international movement for which IDS is the recognised knowledge hub. The Knowledge Hub is dedicated to understanding the on-the-ground realities Breaking the Next Taboo: of CLTS practice and to learn about, share and promote good practices, ideas and Menstrual Hygiene within CLTS innovations that lead to sustainability and scale. We seek to keep the CLTS community Sharon Roose and Tom Rankin, Plan International and well connected and informed and to Sue Cavill, Independent Consultant provide space for reflection, continuous learning and knowledge exchange. We work in collaboration with practitioners, policy-makers, researchers and others working in the development, sanitation and related communities. Ultimately, the Hub’s overarching aim is to contribute to the dignity, health and wellbeing of children, women and men in the developing world who currently suffer the consequences of inadequate or no sanitation and poor hygiene. Front cover A SCHOOL IN TORORO DISTRICT, UGANDA CREDIT: PLAN INTERNATIONAL Correct citation: Roose, S., Rankin, T. and Cavill, S. (2015) ‘Breaking the Next Taboo: Menstrual Acknowledgements Hygiene within CLTS’, Frontiers of CLTS: Innovations and Insights Issue 6, Brighton: IDS First published in 2015 We would like to acknowledge the work done by Sarah House © Institute of Development Studies 2015 (Independent Consultant), who developed the first draft of this Some rights reserved – see copyright license for details.