School-Based Deworming in Cross River State, Nigeria Process Monitoring and Coverage Validation Report, October 2018 Round

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’S Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y

Programme Division Towards Better Programming Guidelines Series AA ManualManual onon SchoolSchool SanitationSanitation andand HygieneHygiene In Collaboration with Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 September 1998 A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’s Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unicef.org A publication of UNICEF/Programme Division Water, Environment and Sanitation ID No. UNICEF/PD/WES/98-5 This School Sanitation and Hygiene Manual is one of the Technical Guidelines Series prepared by the Water, Environment and Sanitation Section, Programme Division, UNICEF, in collaboration with the IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, The Netherlands. Titles of other publications in this series are printed on the inside back cover of this Manual. For further information contact: Water, Environment and Sanitation Section Programme Division, UNICEF 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 Tel (212) 824-6669; Fax: (212) 824-6480 e-mail: [email protected] IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre P.O. Box 93190 2509 AD The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 (0)70 3068930, Fax: +31 (0)670 3589964, E-mail: [email protected] Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Towards Better Programming A manual on school sanitation and hygiene United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre 1998 Table of contents Acknowledgements vii Preface iix 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Importance of school sanitation and Hygiene 1 1.2 Purpose and set-up of the manual 3 1.3 Scope of the manual 3 1.4 For whom are this manual intended 4 1.5 UNICEF's role as catalyst 4 1.6 Who contributed to this manual 4 PART I SCHOOL SANITATION AND HYGIENE AT DISTRICT AND NATIONAL LEVEL 2. -

Eket, Cross River State

Problems of industrial fisheries development in the Cross River State Item Type conference_item Authors Essien, J. Download date 24/09/2021 14:50:33 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/21086 14 PRO3LEMS OF INDUSTRIAL TISHERXES DEVELOPMENT IN THE CROSS RIVER STATE by James Essico Seastate Seafoods Ltd., Eket, CrossRiver State A S S T R A C T T1i paper describes briefly the industrial fisheries as opposed to artisanal fisheries in the Cross River State. It gives a brief description on the prospect of industrial fisheries in the State and proceeds further to identify the major fish and shrimp resources within the coastal waters. It dosis briefly on the introduction of industrial fishing in 1973 when the State Government invited Japaneese Company to carry out a joint exploratory shrimp fishing venture and also the government's oferte to acquire a stern trawler for exploratory fishing. The contributions made by the Seastate Seafoods Company, the Eyib's Nutritional Food and the Arawak Fishing Companies towards the increase in the number of fishing fleet in the State are noted. the major causes of the decline in the industrial fisheries are briefly discussed. These include the management problems, inadequate tinancing, lack of civalified personnel to operate the vessels, poor uaíntsnance facility and lack of supporting infrastructure. it discusses the effects of the development of offshore oil on coastal fisheries, The recommendations include supervised credit, development of basic infrastructure and boat building, standardising cquipment for fishing vessels andprotection of our coastRi waters. LNTROI)UCT ION ?ishing industry in the Cross River State is dominated by the artisanal fisheries which involves the use of canoes both mechanised end unmechanised. -

Rspo Notification of Proposed New Planting

RSPO NOTIFICATION OF PROPOSED NEW PLANTING This notification shall be on RSPO website for 30 days as required by the RSPO procedures for new plantings (http://www.rspo.otg/?q=page/535). It has also been posted on local on-site notice boards. Tick whichever is appropriate √ This is a completely new development and stakeholders may submit comments This is part of an ongoing planting and is meant for notifications only Company : Biase Plantation Limited (Calaro Extension) Subsidiary : Wilmar International Limited RSPO Membership No: 2-0017-05-000-00 on behalf Wilmar International Limited since on 15 August 2005 Location of Proposed New Planting: Atan Odot village and Uwet village, Odukpani and Akamkpa Local Government Area, Cross River State, Nigeria. GPS Reference: Calaro Extension Area of Biase Plantation Limited is geographically located on Latitude: 80 16‘51“to 80 21‘26“North and Longitude: 50 15‘ 30“ to 50 17‘ 47“ East. 1 RSPO New Planting Procedure Assessment Report CALARO Extension Estate of Biase Plantation Ltd – Cross River State, Nigeria Location of the Proposed New Planting Total area acquired by Biase Plantation Limited (BPL) according to the MoU between the government of Cross River State of Nigeria and Uwet & Atan Odot Communities / Ikot Eyidok dated on 10 January 2013 and MoU between the landlord communities and Biase Plantation Ltd dated on 10th December 2015 is 3,066.214ha (shown on survey plan no. RIU/CR/191/12). This included potential overlaps with the Uwet-Odot Forest Reserve and the Oban Forest Reserve. Subsequent re-demarcation has excluded the areas of overlap and reduced the total concession area to 2,368.94 Ha (Deed of grant between the government of Cross River State of Nigeria and Biase Plantations Ltd). -

Biography of Obudu Cattle Ranch Obudu Cattle Ranch This Amazing Place Was Established in the Year 1951

Biography of Obudu Cattle Ranch Obudu Cattle Ranch This amazing place was established in the year 1951. Its founders are Scottish ranchers M. McCaughley and Mr Hugh Jones together with Dr Crawfeild. When McCaughley was discovering the mountain ranges, he considered this territory a perfect spot for a ranch. And this is how the history of the Obudu Ranch started. Now, it is a well-known Nigeria resort and recreational place. The Obudu Mountain Resort is located in Cross River State. This place is surrounded by gorgeous mountains and green hills which will definitely captivate your eyes, mind and soul. Once you visit the resort, you will not want to leave it. It is a perfect place for reuniting with nature and find peace for your thoughts. You can take a bus to the Obudu Ranch. You can use the direct route from Calabar. It will take you right to the town of Obudu. This option is the fastest one, as other buses make a couple of stops during the way. The trip to Obudu from Calabar takes about five or six hours. You will then need an another extra hour to get to the ranch itself, and we assure you that this will be the best hour of your trip as the views from windows will amaze you. Right, we pay for accommodation. Obudu Cattle Ranch has reasonable prices for beautiful, comfortable and commodious suites. It offers several rooms which can be suitable for everyone. The prices vary from 62 US dollars to 209 US dollars per night. These are the options of rooms from the cheapest to the most expensive one: • Standard double chalet • Superior double • African Hut • Club Chalet • Superior double + deal of the season • Executive suite • Royal suite • Presidential lodge • Governor's place • Mountain Villa The cable car ride can be considered one of the most popular reasons to visit the Obudu Mountain Resort. -

Accessibility of Hiv/Aids Information to Women In

International Journal of Ebola, AIDS, HIV and Infectious Diseases and Immunity Vol.4, No.1, pp.1-11, April 2017 __Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) AVAILABILITY OF HIV/AIDS INFORMATION TO WOMEN IN IKOM LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA Felicia U. Iwara CLN Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Library, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: The study was carried out to determine how HIV/AIDS information was made available to women in Ikom Local Government Area. Survey method was used through the administration of questionnaire. 300 copies of the questionnaire were distributed. The return was 90%. It was revealed that, due to poverty and the low level of education, the women found it very difficult to have access to available HIV/AIDS information whenever it was made available. It is therefore, recommended that adult schools should be established in all Local Government Areas of Cross River State especially Ikom Local Government Area to educate the women and sensitize them about the dangers of this deadly disease and how to prevent it especially from mother-child. By educating the women, it will enable them access available HIV/AIDS information at the appropriate time. Women should be empowered so that, they do not rely entirely on men financially. KEYWORDS: Availability, HIV/AIDS, Information, Women, Ikom Local Government, Cross River State INTRODUCTION All over the world HIV/AIDS is causing devastation by its destructive effects on families and economy of the nation. At the end of 2003, a report was issued by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) on the status of HIV/AIDS in the world (UNAIDS/WHO, 2004). -

A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’S Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y

Programme Division Towards Better Programming Guidelines Series AA ManualManual onon SchoolSchool SanitationSanitation andand HygieneHygiene In Collaboration with Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 September 1998 A Manual on School Sanitation and Hygiene Copyright © 1886 United Nations Children’s Fund 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unicef.org A publication of UNICEF/Programme Division Water, Environment and Sanitation ID No. UNICEF/PD/WES/98-5 This School Sanitation and Hygiene Manual is one of the Technical Guidelines Series prepared by the Water, Environment and Sanitation Section, Programme Division, UNICEF, in collaboration with the IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, The Netherlands. Titles of other publications in this series are printed on the inside back cover of this Manual. For further information contact: Water, Environment and Sanitation Section Programme Division, UNICEF 3 United Nations Plaza, TA-26A New York, N.Y. 10017 Tel (212) 824-6669; Fax: (212) 824-6480 e-mail: [email protected] IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre P.O. Box 93190 2509 AD The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 (0)70 3068930, Fax: +31 (0)670 3589964, E-mail: [email protected] Water, Environment and Sanitation Technical Guidelines Series - No. 5 Towards Better Programming A manual on school sanitation and hygiene United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre 1998 Table of contents Acknowledgements vii Preface iix 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Importance of school sanitation and Hygiene 1 1.2 Purpose and set-up of the manual 3 1.3 Scope of the manual 3 1.4 For whom are this manual intended 4 1.5 UNICEF's role as catalyst 4 1.6 Who contributed to this manual 4 PART I SCHOOL SANITATION AND HYGIENE AT DISTRICT AND NATIONAL LEVEL 2. -

Nigeria - Accessibility to Emonc Facilities in the State of Cross River

Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities in the State of Cross River Last Update: March 2016 Nigeria - Accessibility to EmONC facilities for the Cross River State Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 5 2. Measured indicators and assumptions .................................................................................... 5 3. Tool used for the different analyses: AccessMod 5.0 ............................................................. 7 4. Data and national norms used in the different analyses .......................................................... 8 4.1 Statistical Data ............................................................................................................... 9 4.1.1 LGA Number of pregnant women for 2010 and 2015 ........................................... 9 4.2 Geospatial Data ........................................................................................................... 12 4.2.1 Administrative boundaries and extent of the study area ...................................... 13 4.2.2 Geographic location of the EmONC facilities and associated information ......... 17 4.2.4 Transportation network ........................................................................................ 26 4.2.5 Hydrographic network ........................................................................................ -

Menstrual Hygiene Management Policy

REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF HEALTH MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT POLICY 2019-2030 a REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF HEALTH MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT POLICY 2019-2030 Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................v Preface .................................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgement ............................................................................................................................. vii Acronyms/Abbreviations .................................................................................................................viii Glossary/Definition of Terms............................................................................................................ x 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Situational Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Information, Knowledge and Awareness on Menstruation ............................................ 1 1.1.2 Knowledge of and Access to Menstrual Management Products .................................. 2 1.1.3 MHM in Learning Institutions .............................................................................................. -

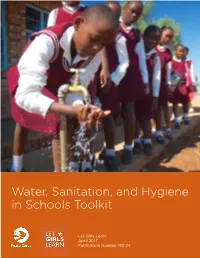

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit and Hygiene Sanitation, Water, Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit Let Girls Learn April 2017 Publication Number M0124 Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools Toolkit Office of Global Health and HIV April 2017 Publication No. M0124 The Peace Corps is committed to providing access and reasonable accommodations to individuals with disabilities. Should you require this material in an alternate format, please contact the Office of Civil Rights and Diversity at 202-692-2139 or [email protected]. Acknowledgments The Peace Corps WASH in Schools Toolkit was developed by Janet Holt, public health program specialist, and Emily Hoppes, program support assistant, in the Office of Global Health and HIV (OGHH) in conjunction with the Peace Corps Let Girls Learn Program. Content was provided by Monique Widyono, gender specialist with Let Girls Learn in the Office of Overseas Programming and Training Support (OPATS). In addition, editing and publishing oversight was provided by Laura Pirocanac, strategic content and design manager, OPATS. Field input was provided by staff and Volunteers from Peace Corps/ Ghana, Peace Corps/Togo, and Peace Corps/Madagascar. Significant guidance was provided by the USAID/WASHplus Project led by FHI 360. The authors would also like to acknowledge the leadership and support provided by Shelley Smith, chief of programming and training in OGHH, and Krista Rigalo, program director of the Peace Corps Let Girls Learn Program. The Peace Corps gratefully acknowledges the talent and skills of the authors who provided authorization for use of their materials in this manual: USAID; WHO; GIZ; Mark Tiele, Westra Werkgroep Ontwikkelings Technieken, University of Twente; U.S. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT FEBRUARY 13, 2019 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Nkwor Market Square, Adazi- Enu, Anaocha Local Govt, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 16 Adazi-Nnukwu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Near Eke Market, Adazi Nnukwu, Adazi, Anambra State ANAMBRA 17 Addosser Microfinance Bank Limited State 32, Lewis Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State LAGOS 18 Adeyemi College Staff Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Adeyemi College of Education Staff Ni 1, CMS Ltd Secretariat, Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo ONDO 19 Afekhafe Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit No. -

Resolving Resource Conflict in Nigeria: a Case of Akwa Ibom and Cross River States

Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (OMAN Chapter) Vol. 2, No.3; Oct. 2012 RESOLVING RESOURCE CONFLICT IN NIGERIA: A CASE OF AKWA IBOM AND CROSS RIVER STATES. Alao, D.O Ph.D, Ndem, Bassey Ph.D, Atere, Olusegun, Clement, Nwogwugwu, N. and Ojo, O.1 BABCOCK UNIVERSITY, ILISHAN REMO, OGUN STATE,NIGERIA ABSTRACT The Supreme Court Judgment of June 12, 2012 transferring 76 oil wells to Akwa Ibom State following the litigation by Cross River State, brought to the fore the politics of oil resources This motivates the study to examining the mechanism for resolving resource conflicts in Nigeria.. This paper adopted the historical, descriptive and analytical approach as its method of study and qualitative in nature. The study found that political approach and incorporation of traditional norms and values are preferable as a means of solving socio-economic differences among friendly states rather than resorting to litigation. It concludes such disputes are manifestation weak state reflecting in lack of effective institutional mechanisms for resolving conflicts. The study recommends an inclusive mechanism in resource allocation like in Alaska while conciliation and arbitration method should be adopted at the expense of litigation in line with constitutional provisions as this will gradually demystify statetism. 1. INTRODUCTION The issue of boundary and the administration of resources along the boundary line will for a long time constitute a challenge that the government in Nigeria would have to cope with in order to ensure peaceful coexistence among various ethnic nationalities. The terms "border" and "boundary" are physical in origin. Johnson and Machelsen, (1997) observe in most cases, it has a wider meanings in political and economic geography than “frontiers,” which refers to a special case of border used to divide the sovereign limits of adjacent independent according to Guo (2005). -

UNHCR Nigeria

OPERATIONAL UPDATE Cameroonian Refugees in Nigeria June 2021 Some 67,000 UNHCR commemorates World About 13,000 refugees received Cameroonian refugee Refugee Day on 20 June with cash to purchase food of their men, women and children thousands of refugees, government choice in Benue and Cross River are registered in Akwa- authorities, partners, and host States this month. Ibom, Benue, Cross River communities in Nigeria. and Taraba States in Nigeria. Solidarity match to commemorate World Refugee Day 2021 by UNHCR, refugees, government officials and host communities in Ogoja, Cross River State. © UNHCR /Lucy Agiende. www.unhcr.org 1 CAMEROON REFUGEE OPERATIONAL UPDATE JUNE 2021 Operational Highlights ■ On 20 June, UNHCR, government authorities, refugees, host communities and partners came together to commemorate the World Refugee Day (WRD) and celebrate the courage/resilience of refugees in Nigeria. A week-long commemoration was undertaken with several activities including solidarity walk, cultural displays, musical performances, friendly soccer games by adults and children, fashion parade, livelihood exhibitions, COVID-19 vaccination, essay/debate competitions and exhibitions of handcraft/technological inventions in Akwa Ibom, Benue, Cross River and Taraba States. PROTECTION Protection Monitoring ■ UNHCR collaborated with twelve government agencies, national and international partners to systematically identify protection incidents, analyse the protection risk and refer cases to partners providing protection and multisectoral assistance, including legal assistance, registration/documentation, advocacy, capacity building, awareness sessions, services related to Gender-Based Violence (GBV) and material assistance. ■ In Benue, Cross River and Taraba (BCT) States, UNHCR and partners undertook at least 30 Joint border monitoring visits, to assess the presence and needs of new arrivals, advocate for the protection of refugees and ensure that refugees have access to territory.