Sahitya Akademi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Female Protagonists in the Novels of Anita Nair: a Feminist Perspective”

“FEMALE PROTAGONISTS IN THE NOVELS OF ANITA NAIR: A FEMINIST PERSPECTIVE” A THESIS SUBMITTED TO BHARATI VIDYAPEETH DEEMED UNIVERSITY, PUNE FOR AWARD OF DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNDER THE FACULTY OF ARTS, SOCIAL SCIENCES AND COMMERCE SUBMITTED BY MS. POONAM DNYANDEO PATIL M. A., B.Ed. UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. V.A. RANKHAMBE M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D. RESEARCH CENTRE DEPATMENT OF ENGLISH BHARATI VIDYAPEETH DEEMED UNIVERSITY YASHWANTRAO MOHITE COLLEGE OF ARTS, SCIENCE AND COMMERCE, PUNE 411 038 AUGUST, 2017 I DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Female Protagonists in the Novels of Anita Nair: A Feminist Perspective” submitted by me to the Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English under the faculty of Arts, Social Sciences and Commerce, is original piece of work carried out by me under the supervision of Dr. V. A. Rankhambe. I further declare that it has not been submitted to this or any other university or Institute for the award of any Degree or Diploma. I also confirm that all the material which I have borrowed from other sources and incorporated in this thesis is duly acknowledged. If any material is not duly acknowledged and found incorporated in this thesis, it is entirely my responsibility. I am fully aware of the implications of any such act which might have been committed by me inadvertently. Place: Pune Date: / 08 /2017 Ms. Poonam Dnyandeo Patil (Research Student) II CERTIFICATE OF THE GUIDE This is to certify that the work incorporated in the thesis entitled “Female Protagonists in the Novels of Anita Nair: A Feminist Perspective” submitted by Ms. -

2016-17-New.Pdf

1 ALMAS the college newsletter for the year 2016-17 de- picts the advancement of Al-Ameen College, Edathala, Aluva over the period of the past year. The activities of the institution are charted out with the needs of the students in mind. Education has a wider dimension in the world of today that exceeds by far the boundaries of an academic syllabus. It is to be supplemented with programmes for additional development that will ensure that students obtain a quality education. This education must have the propensity of rousing their awareness of possibilities in avenues of career, of showing them what they need to do in order to achieve their goals and of how they should set about this to achieve success. In addition, student character is to be wrought with the building of strong moral fibre and basic values. Self confidence and self reliance are to be inculcated and compassion for other less fortunate is also to be fostered I take pride in the fact that these objectives have been sought for during the course of the year through activities de- signed to tackle areas that need to be uplifted. I congratulate the editorial board of the newsletter for their diligence in charting and documenting the highlights of the past year. Dr. Anita Nair Principal 2 Message from the Manager I am extremely happy that the 3rd edition of the institutional newsletter ALMAS 2016-17 has been released. The events charted out here are a clear indicator of the progress made by the staff and students in achieving the goals set earlier in the year. -

Introduction the Lower Caste Characters in Indian English Fiction

12 Introduction The Lower Caste Characters in Indian English Fiction The Rise of Indian Novel: Human being is a peculiar social animal on the planet. One of the distinctive aspects of human beings compared to other animals is their instinctive urge to express their experiences, feelings, joys, sufferings, pains etc.; and literature is one of the media for this. In the early phases of human history, oral narrative traditions catered to this urge. Later on, literature, as a form of human expression, evolved with genres like poetry, drama, fiction, and so forth. Therefore, literature possibly can best be described by situating it in its socio-cultural phenomena, as no literature can be produced in a vacuum. The novel, as a literary phenomenon, is pre-eminently a social form, and is concerned with social issues and relationships. The novel, as one of the major and most effective forms of literature, “gives artistic form to the relationship of man and society,” and is “the organic product of a particular environment in a particular society in a given time.”1 It is deeply rooted in the socio-political, economic and cultural facets of the society. It frequently mirrors life, thereby becoming a representation of the society. Henry James’ opinion aptly sums up the connection between the novel and society: “The only reason for the existence of a novel is that it does attempt to represent life.”2 Henry James, in “The Art of Fiction” (1884), argues that the art of the painter and the art of the novelist is analogous. He draws an analogy between the painter and the novelist while giving a general description of the novel thus: [A]s the picture is reality, so the novel is history…The subject matter of fiction is stored up likewise in documents and records, and if it will not give itself away, as they say in California, it must speak with assurance, with the tone of the historian.3 Thus, it can be said that the rise of the novel in India is not merely a literary phenomenon, but pre-eminently a social one. -

Background to the Indian Prose

Chapter 5 Background to the Indian Prose 5.0 Objectives 5.1 Introduction 5.2 History of Indian English Prose in brief 5.3 Major Indian English Prose Writers 5.4 Major themes dealt in Indian English Prose 5.5 Conclusion 5.6 Summary Answers to check your progress 5.7 Field work 5.0 Objectives Friends, the Second Semester of Indian English Literature paper deals with the Indian Prose works. Study of this chapter will help you to : ● Describe the literary background of the Indian English Prose. ● Take review of the growth and development of Indian English Prose. ● Describe different phases and the influence of the contemporary social and political situations. ● Explain recurrent themes in Indian English prose. ● Write about major Indian English prose writers. 5.1 Introduction Friends, this chapter will introduce you to the history of Indian English prose. It will provide you with information of the growth of Indian English prose and its socio-cultural background. What are the various themes in Indian English prose? Who are the major Indian English prose writers? This chapter is an answer to these questions with a thorough background to Indian English prose works which will Background to the Indian Prose / 67 help you to get better knowledge of the various prevailing trends in Indian English prose works. 5.2 History of Indian English Prose in brief Indo - Anglian Literature 1800-1970 is broadly speaking a development from poetry to prose and from romantic idealization of various kinds to realism and symbolism. But one has to admit that Indian writing in English is the off - spring of the English impact on India. -

Women in Pre- and Post-Victorian India: the Use of Historical Research in the Writing of Fiction

Radhika Praveen/05039123 Vol 1 of 2 Creative Writing PhD Vol 2 Women in pre- and post-Victorian India: The use of historical research in the writing of fiction by Radhika Praveen This practice-based thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of London Metropolitan University for a Doctorate of Philosophy degree in Creative Writing. September 2018 1 Radhika Praveen/05039123 Vol 1 of 2 Creative Writing PhD This work is dedicated to both my grandmothers, Devaki Amma, and Saroja Iyengar. A deep regret that I could not spend much time with my paternal grandmother, Devaki Amma (Achchamma), is probably reflected in my novel. Memories with her are few, but they will last forever. For my dear Ammamma, Saroja, who has always lamented the lack of formal education in her life: this doctorate is for you. 2 Radhika Praveen/05039123 Vol 1 of 2 Creative Writing PhD Abstract This practice-based creative writing doctorate supports the creation of a novel that is in part, historical fiction, based on research focusing on the discrepancies in the perceived status of women between the pre-Victorian and the postmillennial periods in India. The accompanying component of the doctorate, the analytical thesis, traces the course of this research in connection to the novel's structural development, its narrative complexity and its characters. The novel traces the journey of two women protagonists – each placed in the 18th- and the 21st-centuries, respectively – as they reconcile to the realities of their individual circumstances. The introduction to the critical thesis gives a brief synopsis of the novel. -

Library Details the Library Has Separate Reference Section/ Journals Section and Reading Room : Yes

ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST’S COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, NEDUMKUNNAM Library Details The Library has separate reference section/ Journals section and reading room : Yes Number of books in the library : 8681 Total number of educational Journals/ periodicals being subscribed : 23 Number of encyclopaedias available in the library : 170 Number of books available in the reference section of the library : 1077 Seating capacity of the reading room of the library : 75 Books added in Last quarter Number of books in the library : 73 Total number of educational Journals/ periodicals being subscribed : 1 Number of books available in the reference section of the library : 9 Library Stock Register ACC_NO BOOK_NAME AUTHOR 1 Freedom At Midnight Collins, Larry & Lapierre, Dominique 2 Culture And Civilisation Of Ancient India In Historical Outline Kosambi,D.D. 3 Teaching Of History: A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 4 Teaching Of History:a Practical Approach Aggarwal,j.c. 5 School Inspection Ststem:a Modern Approach Singhal, R. P. 6 Teaching Of Social Studies : A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 7 Teaching Of Social Studies: A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 8 School Inspection System: A Modern Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 9 Fundamentals Of Classroom Teaching Taiwa, Adedison A. 10 Introduction To Statistical Methods Gupta, C. B. & Gupta, Vijay 11 Textbook Of Botany Vol.2 Pandey, S. N. & Others 12 Textbook Of Botany. Vol 1 Pandey, S. N. & Trivedi, P. S. 13 Textbook Of Botany. Vol.3 Pandey, S. N. & Chadha A. 14 Principles Of Education Venkateswaran, S. 15 National Policy On Education: An Overview Ram, Atma & Sharma, K. D. -

Methodology of Literature (2015 Admissions Onwards) Time: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 80 I

Methodology of Literature (EN5BO3) STUDY MATERIAL UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT V SEM B.A. ENGLISH CORE COURSE PREPARED BY www.literariness.org www.literariness.org Page 2 MODULE 2 TEXTUAL APPROACHES RUSSIAN FORMALISM Russian Formalism, which emerged around 1915 and flourished in the 1920s, was associated with the OPOJAZ (Society for the Study of Poetic Language) and with the Moscow Linguistic Society (one of the leading figures of which was Roman Jakobson) and Prague Linguistic Circle (established in 1926, with major figures as Boris Eichenbaum and Viktor Shklovsky). The school derives its name from ―form‖, as these critics studied the form of literary work rather than its content, emphasizing on the ‗formal devices‘ such as rhythm, metre, rhyme, metaphor, syntax or narrative technique. Formalism views literature as a special mode of language and proposes a fundamental opposition between poetic/literary language and the practical/ordinary language. While ordinary language serves the purpose of communication, literary language is self-reflexive, in that it offers readers a special experience by drawing attention to its ―formal devices‖, which Roman Jakobson calls ‗literariness‘ — that which makes a given work a literary work. Jan Mukarovsky described literariness as consisting in the ―maximum of foregrounding of the utterance‖, and the primary aim of such foregrounding, as Shklovsky described in his Art as Technique, is to ―estrange or ―defamiliarize‖. Thus literary language is ordinary language deformed and made strange. Literature, by forcing us into a dramatic awareness of language, refreshes our habitual perceptions and renders objects more perceptible. Though Formalism focused primarily on poetry, later Shklovsky, Todorov and Propp analysed the language of fiction, and the way in which it produced the effect of defamiliarization. -

Institute of Distance and Open Learning Gauhati University

ENG-02-16 Institute of Distance and Open Learning Gauhati University MA in English Semester 4 Paper 16 Contemporary Indian Writing in English-I Contents: Block 1: History of Indian English Literature Block 2: Poetry (1) Contributors: Block 1: History of Indian English Literature Units 1, 2 & 3 Saurabhi Sharma Research Scholar, Dept. of English Gauhati University Block 2: Poetry Units 1 & 3 Ranjita Choudhury Dept. of English Guwahati Commerce College. Unit 2 Dr. Runjun Devi Dept. of English Mangaldoi College, Mangaldoi Units 4 & 5 Kalpana Bora Research Scholar, Dept. of HSS, IIT Guwahati Editorial Team Dr. Kandarpa Das Director, IDOL, GU Dr. Uttara Debi Assistant Professor in English IDOL, GU Sanghamitra De Guest Faculty in English IDOL, GU Manab Medhi Guest Faculty in English IDOL, GU Cover Page Designing: Kaushik Sarma Graphic Designer CET, IITG February, 2012 © Copyright by IDOL, Gauhati University. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise. Published on behalf of Institute of Distance and Open Learning, Gauhati University by Dr. Kandarpa Das, Director, and printed at Maliyata Offset Press, Mirza-781125. Copies printed 1000. Acknowledgement The Institute of Distance and Open Learning, Gauhati University duly acknowledges the financial assistance from the Distance Education Council, IGNOU, New Delhi, for preparation of this material. (2) Contents Page No. Block 1: History of Indian English Literature Block Introduction 5 Unit 1: Beginnings 7 Unit 2: Early Twentieth Century 25 Unit 3: Post-Independence Period 49 Block 2: Poetry Block Introduction 75 Unit 1: Jayanta Mahapatra 79 Unit 2: Keki N Daruwalla 103 Unit 3: Kamala Das 127 Unit 4: Adil Jussawalla 149 Unit 5: Vikram Seth 167 (3) (4) Block 1: History of Indian English Literature Block Introduction This block brings to you the literary history of Indian literature in English. -

Abstract Indian English Literature Begins from 1800 Roughly

Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, {Bi-Monthly}, ISSN 2249-9598, Volume-09, Apr 2019 Special Issue (03) Contributions of Indian English Novelists for the Growth of Indian English Literature Ganesh Prasad S G Assistant Professor, Dept. of P.G Studies in English, Alva’s College, Moodbidri, India Abstract Indian English literature begins from 1800 roughly. The British domination swept all aspects of Indian life since then. The Dutch, French and Portuguese from the outside and the Marathas from the inside had almost lost their powers. That is to say the Battle of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764) changed the destiny of the British as well as Indians altogether. Dean Mahomed (1759-1851) was affected by this. Originally from Patna, he served the Mughals and he left them when they lost power, and he settled in the UK. His book The Travels of Dean Mahomet (1794) was the first book ever written by an Indian in English.. The British did mapping of the Indians’ intellectual, cultural and historical dimensions. The Orientlists Sir Charles Wilkins, Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, Sir William Jones, John Gilchrist and Henry Colebroke worked in comparative philology, lexicography and translation. In his Asiatic Researches, Jones laying foundation for historical linguistics, said: “Sanskrit, Greek and Latin have sprung from a common source.’ Gradually Raja Rammohan Roy, and Lord Macaulay’s ‘Minute on Education’ introduced English as a medium of education in India. Macaulay observed: “We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals, and in intellect.” So Indians of the upper class, and caste, began learning English for jobs and some of them started writing prose in the new medium. -

Chinmaya Vidyalaya Thrissur Annual Report 2019-20

CHINMAYA VIDYALAYA THRISSUR ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 Hari om, A warm good evening to one and all assembled here. Pranams to the supreme Lord and humble salutations to Pujya Gurudev H.H. Swami Chinmayanandaji. Respected members on the dais, invited dignitaries, parents, teachers and dear students Years back , Poojya Gurudev had a vision where children were the focal point, a vision to transform our country through our children, a vision to make them empowered in different areas. This vision is now fructified as we find our children scripting history at the National level. Chinmaya Vidyalya Thrissur is gaining National & International recognition and progressing by leaps and bounds, First came the class X CBSE 2019 results where 2 of our children Bhamasree S & Anaika Afsal created history by securing 99 percentage aggregate and standing 5th in Ranking at National level. Prayers, hopes Excitement, dreams and blessings enabled our young heros who donned the jersy of Chinmaya Vidyalaya Kerala to become runners of the CBSE National Level in the U- 19 Football Tournament thus scripting history. Then came the silver lining of being one among 2000 . Devi Nanda of Class IX had the life time opportunity of being selected as one 2000 children of India to personally interact with Honorable Prime Minister Narendra Modi for a special programme referred as “Pareeksha Pe Charcha” Yes … we are living up to the expectation of our Poojya Gurudev & we shall continue so. I am extremely happy to present before you the annual report for the academic year 2019 20. Academic excellence has always been one of our prime goals. -

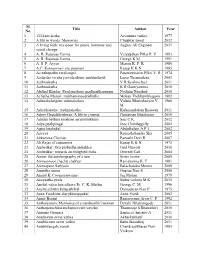

List of Biographies Availabe in KCHR Archive

Sl. Title Author Year No. 1 1114-nte katha Accamma varkey 1977 2 A life in words: Memories Chughtai Ismat 2012 3 A living faith: my quest for peace, harmony and Asghar Ali Engineer 2011 social change 4 A. R. Rajaraja Varma Velayudhan Pillai P. V 1993 5 A. R. Rajaraja Varma George K M 1991 6 A. S. P. Ayyar Menon K. P. K 1980 7 A.C. Kannan nair oru patanam Kurup K K N 1985 8 Aa ezhupathu varshangal Parameswaran Pillai V. R 1974 9 Aadarsha vivaha jeevithathinte anubhuthiyil Lazar Thermadam 2003 10 Aathmakatha V R Krishna Iyer 2011 11 Aathmakatha K R Gauriyamma 2010 12 Abdhul Khadar: Paadanothoru madhurithaganam Nadhim Naushad 2010 13 Achutha Menon: mukhammoodiyillathe Mohan Thekkumbhagom 1992 14 Adimakalengane udamakalaye Vishnu Bharatheeyan V. 1980 M 15 Adiyitharathe: Aathmakatha Kalamandalam Kesavan 2011 16 Adoor Gopalakrishnan: A life in cinema Gautaman Bhaskaran 2010 17 Aduthu bellinu natakam aarambhikkum Sasi C K 2012 18 Adya pushpangal Jose Chittilappilly 2002 19 Agnichirakukal Abdulkalam A P J 2002 20 Agyeya Rameshchandra Sha 2005 21 Akkamma Cherian Parvathi Devi R 2007 22 Ali Rajas of cannanore Kurup K K N 1975 23 Ambedkar: Oru prabudha indiakkai Gail Omvedt 2010 24 Ambedkar: towards an enlighted India Omvedt Gail 2004 25 Amen: the autobiography of a nun Sister Jesme 2009 26 Ammannoor chachu chakyar Ramavarma K. T 1981 27 Ammayane Sathyam Balachandra Menon 2009 28 Amrutha smrui Guptan Nair S 2006 29 Anand K. Coomaraswamy Jag Mohan 1979 30 Anayaatha jwala Shibu vaikom M K 2015 31 Anchal valiachan adhava Fr. C. -

Change and the Persistence of Tradition in India

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA Editorial Board John K. Musgrave George B. Simmons Thomas R. Trautmann, chm. Ann Arbor, Michigan Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-635331 Copyright 1971 by Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-472-03843-5 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12826-6 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90226-2 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ PRE FACE The lectures presented in this volume were given during the summer of 1970 under the sponsorship of the CIC Summer Program on South Asia and the Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies of The University of Michigan. The lecture by A. K. Ramanujan, Professor of Dravidian Studies and Linguis- tics at The University of Chicago ("The Interior Landscape: The Poetic Tradition in Classical Tamil"), and that by Pad- manabha S. Jaini, Professor of Indie Languages and Literatures at The University of Michigan ("Sramanas and their Conflict with Brahmanical Society"), cannot be included because of commit- ments to publication elsewhere. It should be recognized that these essays appear in revised lecture form, and not as fully polished scholarly papers. They carry nevertheless the authority--and no little verve--of ex- perienced scholars concerned both with the traditions and the changes so characteristic of modern India.