Michael Kindellan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

The Thought of What America": Ezra Pound’S Strange Optimism

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO English Faculty Publications Department of English and Foreign Languages 2010 "The Thought of What America": Ezra Pound’s Strange Optimism John Gery University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/engl_facpubs Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Gery, John “‘The Thought of What America’: Ezra Pound’s Strange Optimism,” Belgrade English Language and Literature Studies, Vol. II (2010): 187-206. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English and Foreign Languages at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UDC 821.111(73).09-1 Pand E. John R O Gery University of New Orleans, USA “THE THOUGHT OF What AMerica”: EZRA POUND’S STRANGE OPTIMISM Abstract Through a reconsideration of Ezra Pound’s early poem “Cantico del Sole” (1918), an apparently satiric look at American culture in the early twentieth century, this essay argues how the poem, in fact, expresses some of the tenets of Pound’s more radical hopes for American culture, both in his unorthodox critiques of the 1930s in ABC of Reading, Jefferson and/or Mussolini, and Guide to Kulchur and, more significantly, in his epic poem, The Cantos. The essay contends that, despite Pound’s controversial economic and political views in his prose (positions which contributed to his arrest for treason in 1945), he is characteristically optimistic about the potential for American culture. -

Ezra Pound's Imagist Theory and T .S . Eliot's Objective Correlative

Ezra Pound’s Imagist theory and T .S . Eliot’s objective correlative JESSICA MASTERS Abstract Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot were friends and collaborators. The effect of this on their work shows similar ideas and methodological beliefs regarding theory and formal technique usage, though analyses of both theories in tandem are few and far between. This essay explores the parallels between Pound’s Imagist theory and ideogrammic methods and Eliot’s objective correlative as outlined in his 1921 essay, ‘Hamlet and His Problems’, and their similar intellectual debt to Walter Pater and his ‘cult of the moment’. Eliot’s epic poem, ‘The Waste Land’ (1922) does not at first appear to have any relationship with Pound’s Imagist theory, though Pound edited it extensively. Further investigation, however, finds the same kind of ideogrammic methods in ‘The Waste Land’ as used extensively in Pound’s Imagist poetry, showing that Eliot has intellectual Imagist heritage, which in turn encouraged his development of the objective correlative. The ultimate conclusion from this essay is that Pound and Eliot’s friendship and close proximity encouraged a similarity in their theories that has not been fully explored in the current literature. Introduction Eliot’s Waste Land is I think the justification of the ‘movement,’ of our modern experiment, since 1900 —Ezra Pound, 1971 Ezra Pound (1885–1972) and Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888–1965) were not only poetic contemporaries but also friends and collaborators. Pound was the instigator of modernism’s first literary movement, Imagism, which centred on the idea of the one-image poem. A benefit of Pound’s theoretically divisive Imagist movement was that it prepared literary society to welcome the work of later modernist poets such as Eliot, who regularly used Imagist techniques such as concise composition, parataxis and musical rhythms to make his poetry, specifically ‘The Waste Land’ (1922), decidedly ‘modern’. -

Richard Parker

ON IN MEMORY OF YOUR OCCULT CONVOLUTIONS Richard Parker 317 GLOSSATOR 8 In Memory of Your Occult Convolutions1 1 Keston Sutherland’s ‘In Memory of Your Occult Convolutions’ was written for, and delivered at, a poetry reading organised to coincide with the 24th Ezra Pound Conference, London, July 5-9, 2011. The audience was predominantly made up of Pound scholars from around the world. The poem is constructed from excerpts from essays by Ezra Pound that deal with the relation of pedagogy to literature; ‘How to Read’ (1929), ‘The Serious Artist’ (1913), ‘The Teacher’s Mission’ (1934) and ‘The Constant Preaching to the Mob’ (1916). They are all collected, consecutively, in T.S. Eliot’s edition of the Literary Essays of Ezra Pound (1954) [hereafter LE]. Further extracts are taken from the poems ‘Fratres Minores’ (1914) and Homage to Sextus Propertius (1919), as well as Pound’s early critical work The Spirit of Romance (1910). The ‘Occult Convolutions’ of the title are taken from section 24 (of the 1892 version) of Walt Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’. If I worship one thing more than another it shall be the spread of my own body, or any part of it, Translucent mould of me it shall be you! Shaded ledges and rests it shall be you! Firm masculine colter it shall be you! Whatever goes to the tilth of me it shall be you! You my rich blood! your milky stream pale strippings of my life! Breast that presses against other breasts it shall be you! My brain it shall be your occult convolutions! Root of wash’d sweet-flag! timorous pond-snipe! nest of guarded duplicate eggs! it shall be you! Mix’d tussled hay of head, beard, brawn, it shall be you! Trickling sap of maple, fibre of manly wheat, it shall be you! Sun so generous it shall be you! Vapors lighting and shading my face, it shall be you! You sweaty brooks and dews it shall be you! Winds whose soft-tickling genitals rub against me it shall be you! Broad muscular fields, branches of live oak, loving lounger in my winding paths, it shall be you! Hands I have taken, face I have kiss’d, mortal I have ever touch’d, it shall be you. -

Report Title Raabe, Wilhelm Karl = Corvinus, Jakob (Pseud.)

Report Title - p. 1 of 672 Report Title Raabe, Wilhelm Karl = Corvinus, Jakob (Pseud.) (Eschershausen 1831-1910 Braunschweig) : Schriftsteller Biographie 1870 Raabe, Wilhelm Karl. Der Schüdderump [ID D15996]. Ingrid Schuster : Raabe verwendet im Roman den chinesischen Gartenpavillon als bezugsreiches Symbol für die zwei Hauptpersonen, der Ritter von Glaubigernd und das Fräulein von St. Trouin, sowie Chinoiserien in Adelaide von St. Trouins Zimmer. [Schu4:S. 162-168] Bibliographie : Autor 1870 Raabe, Wilhelm Karl. Der Schüdderump. In : Westermann's Jahrbuch der Illustrirten deutschen Monatshefte ; Bd. 27, N.F. Bd. 11, Oct.1869-März 1870. [Schu4] 1985 [Raabe, Wilhelm]. Que xiang chun qiu. Wang Kecheng yi. (Shanghai : Yi wen chu ban she, 1985). Übersetzung von Raabe, Wilhelm. Die Chronik der Sperlingsgasse. Hrsg. von Jakob Corvinus. (Berlin : Stage, 1857). [ZhaYi2,WC] 1997 [Raabe, Wilhelm Karl]. Hun xi yue shan. Weilian Labei zhu ; Wang Kecheng yi. (Shanghai : Shanghai yi wen chu ban she, 1997). Übersetzung von Raabe, Wilhelm Karl. Abu Telfan : oder, Die Heimkehr vom Mondgebirge : Roman. (Köln : Atlas-Verlag, 1867). [WC] Raaschou, Peter Theodor (Dänemark 1862-1924 Shanghai) : Diplomat Biographie 1907-1908 Peter Theodor Raaschou ist Konsul des dänischen Konsulats in Shanghai. [Who2] 1909-1917 Peter Theodor Raaschou ist Generalkonsul des dänischen Konsulats in Shanghai. 1917 ist er Senior Konsul. [Who2] Raasloff, Waldemar Rudolf (1815-1883) : Dänischer Politiker, General Biographie 1863 Dritte dänische diplomatische Mission nach China durch Waldemar Rudolf Raasloff. [BroK1] Rabban Bar Sauma (ca. 1220-1294) : Türkisch-mongolischer Mönch, Nestorianer Bibliographie : erwähnt in 1992 Rossabi, Morris. Voyager from Xanadu : Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West. (Tokyo ; New York, N.Y. -

Gained in Translation: Ezra Pound, Hu Shi, and Literary Revolution

Gained in Translation: Ezra Pound, Hu Shi, and Literary Revolution Jenine HEATON* I. Introduction Hu Shi 胡適( 1891-1962), Chinese philosopher, essayist, and diplomat, is well-known for his advocacy of literary reform for modern China. His article, “A Preliminary Discussion of Literary Reform,” which appeared in Xin Qingnian 新青年( The New Youth) magazine in January, 1917, proposed the radical idea of writing in vernacular Chinese rather than classical. Until Hu’s article was published, no reformers or revolutionaries had conceived of writing in anything other than classical Chinese. Hu’s literary revolution began with a poetic revolution, but quickly extended to literature in general, and then to expression of new ideas in all fi elds. Hu’s program offered a pragmatic means of improving communication, fostering social criticism, and reevaluating the importance of popular Chinese novels from past centuries. Hu Shi’s literary renaissance has been examined in great detail by many scholars; this paper traces the synergistic effect of ideas, people, and literary movements that informed Hu Shi’s successful literary and language revolu- tions. Hu Shi received a Boxer Indemnity grant to study agriculture at Cornell University in the United States in 1910. Two years later he changed his major to philosophy and literature, and after graduation, continued his education at Columbia University under John Dewey (1859-1952). Hu remained in the United States until 1917. Hu’s sojourn in America coincided with a literary revolution in English-language poetry called the Imagist movement that occurred in England and the United States between 1908 and 1917. Hu’s diaries indicate that he was fully aware of this movement, and was inspired by it. -

China Question of US-American Imagism

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 22 (2020) Issue 5 Article 12 China Question of US-American Imagism Qingben Li Hangzhou Normal Universy Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities -

Textual Attitudes and the Creation of a China in Ezra Pound's Shi Jing Tran

î7 /1 2, Université de Monfréal Preposterous Transitions: Textual Attitudes and the Creation of a China in Ezra Pound’s Shi Jing Translations par Gregory McCormick Département d’études anglaises Faculté des arts et sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.A. en anglais octobre, 2006 ©Gregory McCormick, 2006 R. u5 r3 o Université db de Montréal Dïrecion des bibIotlièques AVIS L’auteur a autorisé l’Université de Montréal à reproduire et diffuser, en totalité ou en partie, par quelque moyen que ce soit et sur quelque support que ce soit, et exclusivement à des fins non lucratives d’enseignement et de recherche, des copies de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse. L’auteur et les coauteurs le cas échéant conservent la propriété du droit d’auteur et des droits moraux qui protègent ce document. Ni la thèse ou le mémoire, ni des extraits substantiels de ce document, ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement reproduits sans l’autorisation de l’auteur. Afin de se conformer à la Loi canadienne sur la protection des renseignements personnels, quelques formulaires secondaires, coordonnées ou signatures intégrées au texte ont pu être enlevés de ce document. Bien que cela ait pu affecter la pagination, il n’y a aucun contenu manquant. NOTICE The author of this thesis or dissertation has granted a nonexciusive license allowing Université de Montréal to reproduce and publish the document, in part or in whole, and in any format, solely for noncommercial educational and research purposes. The author and co-authors if applicable retain copyright ownership and moral rights in this document. -

Modernism Study Guide

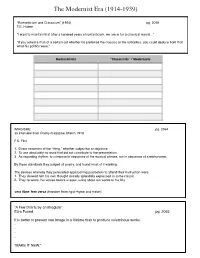

The Modernist Era (1914-1939) “Romanticism and Classicism” (1924) pg. 2059 T.E. Hulme “I want to maintain that after a hundred years of romanticism, we are in for a classical revival...” “If you asked a man of a certain set whether he preferred the classics or the romantics, you could deduce from that what his politics were.” Romanticists “Classicists” / Modernists IMAGISME pg. 2064 an interview from Poetry magazine, March 1913 F.S. Flint 1. Direct treatment of the “thing,” whether subjective or objective. 2. To use absolutely no word that did not contribute to the presentation. 3. As regarding rhythm: to compose in sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome. By these standards they judged all poetry, and found most of it wanting. The devices whereby they persuaded approaching poetasters to attend their instruction were: 1. They showed him his own thought already splendidly expressed in some classic. 2. They re-wrote, his verses before is eyes, using about ten words to his fifty. vers libre: free verse (freedom from rigid rhyme and meter) “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste” Ezra Pound pg. 2065 It is better to present one Image in a lifetime than to produce voluminous works. - - - - “MAKE IT NEW.” Ideogrammic Method (Ezra Pound, Ernest Fenellosa) Imagists prefer adherence to the object. But how, then, do we deal with abstraction? How should one read an Imagist “cluster”? • by considering the “superimposed” • model of the Chinese ideogram • approach abstract concepts/experiences through concrete objects and images What is a manifesto? What do you notice about the genre? Methods of JUXTAPOSING / SUPERPOSING multiple images and objects to express an abstract, complex idea or experience. -

The Exultation of Another the American Beat Poets As Translators

Received: 10 May 2019 | Revised: 9 September 2019 | Accepted: 9 October 2019 DOI: 10.1111/oli.12247 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The exultation of another The American Beat poets as translators Feng Wang1 | Kelly Washbourne2 1Yangtze University, Jingzhou, China The Beat writers' influence on world letters is well known, 2Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA but far less understood is their translational ethos that Correspondence brought the world to American writing. This study offers in- Feng Wang, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, China. sight into a Beat philosophy of translation, whether formal- Email: [email protected] ized or implicit. What emerges is a picture of an expansive Funding information poetics that puts translation in the service of a project of This essay is supported by the Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences identity-formation that actively chose its confederates and Youth Fund (grant number: 15YJC740078) precursors from all over the world's language traditions. For and the National Social Science Fund of China (grant number: Key Project the Beats, translation was sympathy and identification both 17AZD040). textual and biographical, sometimes to the point of projec- tion and creative misreading, and always with a sensibility recognizably tied to their place and time, a Beat translation style. They blurred the lines between original and translation like few generations of writers, including through interpola- tion, “shift linguals,” homage, and other kinds of polyphonic textures. While some of its key figures are already under- stood in their translatorial dimension, considered as a whole, the Beat poets' theories and practices of translation reveal the group to be more multicultural, and more multilingually networked, than perhaps had hitherto been thought. -

Ezra Pound / Henri Michaux): Two Poetics of the Ideogram1

#13 MONTAGE AND GESTURE (EZRA POUND / HENRI MICHAUX): TWO POETICS OF THE IDEOGRAM1 Fernando Pérez Villalón Departamento de Arte / Departamento de Lengua y Literatura Universidad Alberto Hurtado Illustration || Laura Castanedo Translation || Xavier Ortells-Nicolau & Jennifer Arnold 99 Article || Received on: 30/01/2015 | International Advisory Board’s suitability: 11/05/2015 | Published: 07/2015 License || Creative Commons Attribution Published -Non commercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. 452ºF Abstract || This essay compares the way in which writers Ezra Pound and Henri Michaux incorporate a dialogue with Chinese writing in their thought and poetic works, and especifically with the notion of ideogram as a way to understand the nature of Chinese writing. Both Pound and Michaux share an intense fascination with the pictographic dimension of Chinese writing, which they see as less radically divorced from things than alphabetic writing. Pound, however, incorporates the ideogram as an element that is integrated into the montage of quotations, perceptions, anecdotes, and images through which his Cantos are constructed, while for Michaux, the ideogram serves as a starting point to imagine a kind of writing that would be freed from the prisonhouse of meaning. Keywords || Ideogram | Ezra Pound | Henri Michaux 100 0. Introduction: the “Chinese dreams” of Pound and NOTES Michaux 1 | This work is part of the In this essay I propose to compare the way in which Ezra Pound project FONDECYT 1150699, “La imaginación del ideograma: #13 (2015) 99-114. 452ºF. (1885-1972) and Henri Michaux (1899-1984) created an intense entre Pound y Michaux”, led and fertile dialogue with Chinese writing and poetics in their works, by the author. -

"Tinkle, Tinkle, Two Tongues": Sound; Sign; Canto Ninety-Nine

This is a repository copy of "Tinkle, tinkle, two tongues": sound; sign; Canto ninety-nine. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/100616/ Version: Published Version Article: Kindellan, M.R. orcid.org/0000-0001-8751-1433 (2018) "Tinkle, tinkle, two tongues": sound; sign; Canto ninety-nine. Glossator : Practice and Theory of the Commentary, 10. pp. 83-120. ISSN 1942-3381 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ “TINKLE, TINKLE, TWO TONGUES”: SOUND, SIGN, CANTO XCIX Michael Kindellan PREAMBLE Much of the early groundwork for a fuller commentary on this canto has been laid by David Gordon, Carroll F. Terrell, Ben D. Kimpel, T. C. Eaves and Thomas Grieve, with lesser but still very useful contributions by James Wilhelm and Massimo Bacigalupo. More recent work by Chinese scholars Chao-ming Chou, Feng Lan, Haoming Liu, Zhaoming Qian and Rong Ou has given the existing commentary much needed balance. Whether or not a complete gloss of Canto XCIX—the longest canto in Thrones—is possible, let alone either useful or desirable, remains an interesting question I cannot hope to resolve, not least because it seems likely the proper appraisal of Pound’s maverick sinology requires someone with enough linguistic expertise to assess its successes and failures.